William C. Anderson on The Nation on No Map

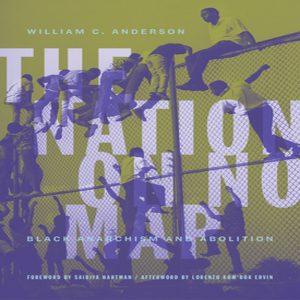

This week we are really pleased to feature Scott conducting an interview with author and activist William C. Anderson about his new book The Nation on No Map: Black Anarchism and Abolition which is out now from AK Press. In this interview they speak on the book and its many facets, and Black anarchism more broadly, some of the failures of euro-centric and white anarchism, and many many more topics.

If you would like to see more of Anderson’s work you can visit https://williamcanderson.info

To see his books The Nation on No Map and As Black As Resistance, you can visit akpress.org and search his name, or visit firestorm.coop and do the same to support a queer and trans run anarchist book store in Asheville <3

Some works and people mentioned by our guest, in order of appearance:

- Martin Sostre introduced Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin to anarchism in 1969.

- Ojore Lutalo was introduced to anarchism by Kuwasi Balagoon.

- Dr. Modibo Kadalie was influential in Anderson’s thinking on anarchism.

- The Anarchism of Blackness (essay) – Zoé Samudzi and William C. Anderson

- Black Fascism – Paul Gilroy (Here is a thread detailing how to access works that are behind a paywall, discretion advised, for entertainment purposes only lmfao 😀 https://www.reddit.com/r/Piracy/comments/3i9y7n/guide_for_finding_textbooks/ )

- The Interminable Catastrophe – Professor Bedour Alagraa

. … . ..

Transcription

(see links above for more context of some of the people and documents mentioned)

Scott Branson – TFSR: I’m very excited to get to talk to William C. Anderson today, whose new book The Nation on No Map: Black Anarchism and Abolition was just published by AK Press. Thank you so much for spending the time to talk to me today. If you want, can you just first introduce yourself with your pronouns and any affiliations or background that you would want to share with the listeners?

William: Yeah, my name is William C. Anderson. I am a writer, activist, and just a person from Birmingham, Alabama. My pronouns are he/him/his, and I’m really excited to be on the show with you today, I’m happy to be talking with you.

TFSR: Likewise. I think this book is a really important contribution. I want to just delve into it. In the book, you’re locating Black anarchism as a practical development in revolutionary action, both in the history of movement work, but also I think, individually, in individual consciousness. I think that’s a super helpful intervention and contribution, thinking about our history, and also strategizing for the future. So I want to talk about both of the moments, movement stuff and individual stuff. I also just want to acknowledge and appreciate that the book is clearly grounded in your own experience. It doesn’t seem like top-down theorizing that often happens. I’m thinking sometimes of ways that white leftist anarchists use Afro-pessimist texts to talk about blackness without being grounded in movement work.

Okay, first, what do you mean by Black anarchism? I see you using this in relation to the legacies of Black Liberation movements of the 60s and 70s. I just want to use this quote, because I think it’s really important. You say “Black anarchism is a break away from the revolutionary Black Power movement, as opposed to simply being an effort to diversify or revise classical anarchism.” I’m wondering if you can talk a little bit about this development in Black revolutionary thinking and why it often gets overlooked for the different ways that the Black Power movement gets represented?

W: Well, this really all starts with Martin Sostre introducing Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin to anarchism in 1969 and federal detention in New York. Lorenzo was a Maoist who fled to Cuba after hijacking a plane where he was imprisoned alongside other Black radicals who were fleeing during that time. He was essentially deported to Czechoslovakia, where he was imprisoned again. Then he fled to East Germany, where the federal authorities caught up with him. He was fleeing originally to Cuba because he had trumped-up charges against him. It was a frame-up for being accused of threatening to bomb a KKK judge. So he decided to flee, he goes to Cuba, he’s in prison there, he goes to Czechoslovakia, he’s detained there, he flees to East Germany, and he’s detained again. He’s tortured in East Germany, too. He is sent to New York. In federal detention, he is clearly upset by his experience with the state socialist governments he had gone to look for a safe haven. With that frustration, he meets Martin Sostre, who is a famous political prisoner at the time, he’s an imprisoned intellectual. He’s a jailhouse lawyer who is repeatedly suing the prison system and actually creating new reforms and gaining new rights for imprisoned people. Through his lawsuits, he completely transforms conditions, almost single-handedly through his litigation. He is talking to Lorenzo about his frustrations and he tells him there is more than state socialism. He tells him, it’s not the only form of socialism, he tells him about stateless or libertarian socialism, which we know is anarchism. Lorenzo starts doing the reading.

A decade later, he writes Anarchism and the Black Revolution. That is the real start of this development in many ways. Other former Panthers and members of the Black Liberation Army are also becoming interested during this period. They’re all thinking about their frustrations within the Black Power movement, with the Black Panther Party, with Marxist-Leninism, with Maoism, etc. They’re all writing and moving accordingly and asking questions. So I don’t think that you can exactly place a location and a time on the birth of Black anarchism because I don’t like to think about history in that way. I think that history is a lot more complicated than trying to place official stamps on things. But that’s really a great way to think about its beginnings with Martin and Lorenzo. You can also complicate that a little bit more if you want to bring in someone like Lucy Parsons, who was obviously doing a lot of writing and speaking about anarchism much earlier, in the early 1900s, late 1800s. This is a formerly enslaved Black woman. But I think what makes a person like Lucy distinct is also that her relationship to her blackness, and to race was a bit more complicated. When we’re thinking about Black anarchism, we’re really thinking about this break away from the Black Power movement, in terms of questioning and disturbing this idea that revolutionary Black nationalism and state socialism together were the only solutions in terms of ways to think about pursuing Black liberation.

TFSR: That’s really helpful. I like how you’re grounding it also, specifically in the material conditions, like the people at that moment were like this, we need something else to look towards. But also the way that you frame it in your book, you’re saying that they’re not just taking on European anarchism, but actually, you make this really telling statement that Black anarchism represents a failure of the anarchist movement in terms of the European tradition of anarchism. I have my understanding of this as what you also talk about in the book, is that Black anarchism isn’t a diversity and inclusion effort of a white anarchism or something like that. It’s actually a critique of anarchism that Black anarchism delivers. So I was wondering if you could expand a little bit on what you see as a failure of European anarchism, and then how a Black anarchism would add what you call “precision”. I really like that word.

W: I could talk about this all day. Historically, I think European anarchists have been self-involved and focused on how they were/are right about the nature of the state in a way that actually limited their appeal. It may be arguable that state socialists were much more effective and thoughtful about bringing Black people and oppressed people of the world into their efforts. Now, that’s not to say that Black people were not met with hostility for bringing up historically what’s known as the race question or the Negro question. There were certainly confrontations that had to be had around race and class that required Black Marxists to challenge conventional white state socialism and Marxism. So I consider, actually, those efforts are part of the legacy of Black autonomous radicalism too. That’s why I draw from an autonomous Marxist like C.L.R. James and my writing. Classical anarchism was not as effective in wrestling with that and it didn’t develop in the same way.

Now, there’s also the factor of the Russian Revolution and other revolutions that were claimed by state socialists, that global impact can’t be ignored in terms of influence. So all of that has to be considered. But Black anarchism isn’t a diversity effort or an effort for inclusion, because it draws influence from the experiences that precede it. Lorenzo was a former Maoist, Martin was a nationalist, former Black nationalist member of the Nation of Islam. Ojore Lutalo had been wrestling with Marxism before Kuwasi Balagoon brings him to anarchism. They didn’t completely discard classical anarchism. Lorenzo, for example, revises it in a way that we can observe parallels, the way that Marxism is revised in the Black radical tradition. What makes it so special is that Black anarchism does that with Marxism too. That’s an important thing to know: it does that with Marxism, with Black nationalism, and with anarchism.

So, in my opinion, because of the way it challenges all of those forms, it transcends the left almost entirely. It rises above conventional leftism. That makes it special. That’s how I’m reading it in this book, it is one of the only places on the left where this confrontation and these revisions happen in so many ways that it actually creates something transformative that shows us how to rise above conventional historical leftisms, and dogma and orthodoxy, to think about creating something completely new. I think that that’s really beautiful. That’s why I’m so just blown away by the writings of Black anarchism, the thinking and the way that they were approaching the left, and the way that they were approaching Black Power and thinking beyond. I think that that’s a beautiful example.

TFSR: What you just said makes me think of this line you have towards the end of the book, which is: “Talking about Black anarchism, it looks at the whole of history and works to uproot oppression by asking the most basic questions about what power is and what gives anyone the right to control or oppress others, even those we share space with. The question is simple, but its implications are vast, influencing the totality of our lives, from race to gender to class and all the many aspects of existence into which power insinuates itself.” I thought about that when you’re talking about these basic questions about our life that anarchism is addressing, but it has this more expansive vision in a way than other approaches. I thought that was really helpful. What you said resonated a lot with that to me. I look to Black feminist writings, and I see versions of anarchism in there that aren’t necessarily called that. That’s something that you talk about in the book, too, that Black thinkers and movement workers have done anarchist work without necessarily calling it that.

I wonder if you want to talk a little bit about what that term means or claiming anarchism or Black anarchism? What value there is in that? Because I know you have a particular relationship to the word itself.

W: Well, there’s a couple of things there. I think the first thing to address is the fact that I have an interesting relationship with the label “anarchist” because I’m not attached to it. I say at the beginning of the text that is not something I run from, and it’s not something that I run to. I’m actually appropriated that from Modibo Kadalie. Because I think that Modibo gets called an anarchist a lot, but that’s not something he necessarily lays claim to. One time I was talking with him, and he said, “I don’t run from anarchism, but I don’t run to it, either.” I adapted that as my outlook. What I mean by that is anarchism, for me, even Black anarchism is not the point. The point is liberation. I think that Black anarchism has amazing insights, that give us important direction to try to come closer to liberation. So, with regard to Black people, Zoé Samudzi and I wrote The Anarchism of Blackness. That led to us writing As Black As Resistance, which leads to this book. What we were talking about in The Anarchism of Blackness, at least one of the core insights of that essay was the fact that Black people have always engaged in these anarchistic, anarchic struggles across the Americas and across the world. That is something that doesn’t require people to lay claim to anarchism as a set of politics.

People have made movements, organizations, and waged fights that didn’t require them to lay claim to anarchism or have some ideological devotion. Many of those things precede anarchism as a political ideology. So, when we look at it that way, it tells you that claiming anarchism is not something that has to happen in order for people to do that work or to do things that are going to make conditions better. I think the most important thing is creating movements that have the principles of anarchism, not laying claim to anarchism as an identity. The last thing I would want to do is try to encourage people to have this rigid, unbending loyalty to dogma and to doctrine, rather than the principles that make those things appealing in the first place. So I think that that’s what’s most important.

TFSR: One of the ways I relate to anarchism is that it teaches us to let go of things that don’t serve us or aren’t useful to us and teaches us how to dissolve things. I think that would have to include anarchism itself as a label. When I was listening to you talk also about the European tradition, it made me think about today, where there’s another blind spot for, say, white anarchists in the inclusion of analysis of racial capitalism, of the history of Black struggle, anarchists are so often wanting to dissolve identities as this effective liberal / neoliberal state, and yet cling to this idea of anarchism as an identity, and to such an extent that it excludes people being able to find an entry point into the work itself. Yes, exactly. In a way, it seems like some of those blind spots from the classical anarchism that you were talking about persist, just in the new form of us.

W: Yeah, they do.

TFSR: Going back to history, you differentiate Black anarchism from other Black Power movements, but you’re also drawing the connections between them. One of the things you talk about in the book is Black nationalism, also Black capitalism. And these are two attempts to find empowerment for Black communities. Now, your book is totally critical of nations and states, but you also caution against just dismissing Black nationalism, or Black nationalist movements, and also specifically try to differentiate between Black nationalism and the white supremacist state and that nationalism. What are your thoughts about what role Black nationalism plays? How there might be potential collaboration? If you want to talk to just about the threat of nationalism more generally?

W: There are different types of nationalism. When we’re thinking about Black nationalism, you have revolutionary nationalism, and you have reactionary nationalism. I think that both need to be wrestled with, I don’t make a distinction between them in the book because I find troubling currents in both. However, I don’t compare Black nationalism that utilizes troubling and even homogenizing rhetoric in any form to white supremacy, that it does it in response to. So for example, I talked about [Marcus] Garvey in the text, and he said that he was the first fascist, he said that Benito Mussolini got fascism from him. Even though he said that he was the first fascist, did he do what Benito Mussolini did? No, he didn’t. I don’t think that Black Fascism is impossible or non-existent. There are certainly Black fascists now and there have been historically. But it’s important to observe what they’re responding to, and what their intentions are. There are parallels and distinctions. I wrote about this some years back, actually, with regard to the Nation of Islam, and I’m thinking about the Nation of Islam’s Black nationalism, specifically. The Southern Poverty Law Center used to have them, I’m not sure if they still do, I think that they took them off, but they used to have them on their hate group listing. I always found that disturbing, because white supremacists have always run this country. You can’t compare that and equate it with Black nationalisms that develop using rhetoric and reasoning that is similar to white supremacists.

In the book, I’m arguing that before it gets to that point, we have to stop now and observe history. We have to not glorify everything and depart from this idea that we’re all going to fall under the form or formation of a nation. The nation and the state are different things. But what many Black nationalisms lean to is the idea of a Black nation-state. That’s not something that comes with no risk for violence, because there’s no essential innocence, as Paul Gilroy says in his paper “Black Fascism” that makes this endeavor holier just because we’re Black. I quote Aimé Césaire in the text as well saying, “one of the values invented by the bourgeoisie in former times that went throughout the world was man.” He says, “we’ve seen what happened with that,” he said, “the other was the nation.“

This idea that the nation, and this idea of the state, even in a Black form, that these things are going to liberate us, this isn’t ours, it’s not ours to say that this is something that we can even use in this way, it is destructive. We’re talking about trying to lay claim to ideas and to forms that we really shouldn’t be trying to own. So, if we look at history, and we even study post-colonial independence movements, it helps us see the atrocity that can occur even in the name of self-described liberatory state-socialist ventures and nation-building is not something that is just this, “hey, this is going to work. This is always good.” It’s not that simple. I’m bothered by people who treat it that way without being honest about a lot of the history and atrocity and really horrific things that have been done in the name of nation-building and state-building. We have to observe that honestly.

TFSR: Yeah. One of the things that you iterate in your book in a few different places is that the stuff that we do has to not only serve survival but struggle against capitalism in the state. We could think that Black nationalism and Black capitalism, both as things that come out of Black movement organizing, have also been not necessarily, like there have been white people in power who’ve been like “Yeah, that sounds okay. It’s not as big a threat as something that’s fully autonomous from those power structures,” which I think is in line with what you were just saying, about not owning those terms.

But on the other hand, when you’re looking at Black capitalism, in the book you talk about how the limited forms of autonomy that have existed within Black communities in the US historically, – specifically you talk about the massacre in Tulsa in 1921, – that the state just will not allow that to persist because to a certain extent, it is completely inimical to the nation itself. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about Black capitalism historically and how it shows up today because it comes up a lot. People like Killer Mike and Beyonce are spouting it. They also claim some affinity for leftist movements in certain ways. So I’m just wondering if you could expand a little bit on the role of Black capitalism?

W: Black capitalism really comes from Nixon. It’s this idea that Black people can utilize capitalism to achieve some betterment, some freedom that we wouldn’t be able to attain otherwise without capitalism. So I think it connects with what I was just saying, in the sense that we’re talking about trying to lay claim to ideas, and two forms of violence that shouldn’t be ours to try to lay claim to, to try to make use of. Black capitalism is connected to the state and this form of violence, that we know is doing us a lot of harm. To try to say that we’re going to make use of it and to achieve our liberation that way is all a part of the bigger picture I’m trying to illustrate using Black anarchism. It’s to say that you cannot reform and change the inner workings of violence that has been structured against us historically and then make it work for us.

That’s the truth with the state. That’s the truth with capitalism. We’re not going to get free by saying we just need to take this pre-existing form of violence that was not created to serve us and paint it black, or paint it red, or whatever the case may be, and say that it’s going to be different, and that is going to be liberatory that time, the gears and the mechanisms that are built into it are going to do what they are intended to do. With regard to the state, that means having a monopoly on violence that is always self-preserving. With capitalism, we know that means an unfettered, unrestricted desire for accumulation and exploitation. So those are not things that are going to help free us, and putting a Black label on them doesn’t do any good for us either.

TFSR: Yeah, and again, your looking to post-colonial Africa shows that clearly. One of the things I’m hearing what you’re talking about now, and this connects to another question I had prepared was the way that blackness gets used often as this monolithic or single-minded thing. But one of the chapters in your book talks about this rewriting of Black history in a relationship to a lost history, of history that is stolen through a mythology of what life was like for people in Africa.

You also connect this to a critique of celebrity, which is slightly different, but I was really excited that you took these things on in your book. But one of the things that I’m really interested in is that you allow for history to be complex and messy, right? You talked about African people who participated in the slave trade knowingly, they didn’t perpetrate the same institutions that the European colonists did, but it isn’t this Black-and-white thing easily. So I was just wondering if you talk a little bit about this mythological use of Africa and the cultural imaginary or if you want to talk about the cult of celebrity, too? Also, how do you think we can not keep simplifying everything or flattening everything out?

W: I think the narrative that’s been created around the slave trade that you can actually see historically and in many forms of white nationalism, that we are royalty fallen from grace, and that we need to reclaim that royalty. It feeds into iterations of Black capitalism that we see now. That’s why I bring both up. Because I don’t think that you can separate the two. You have someone saying that we’re descended from kings and queens and that we come from royalty. What they’re doing is they’re feeding into the idea that wealth and royalty are what gives someone worth and value. So that’s not something that you can separate from Black capitalism now, which argues the same thing in many ways, saying that by accumulating or having large amounts of wealth, we’re going to be free, and that we’re going to be liberated.

I think that it’s important to disrupt this idea that, even if we were descending from kings and queens, that that makes us good, or that makes us better, or that’s why we’re deserving of respect as people. I think that we have to push back against that. So when I look at that connection, it leads me to say, we have to complicate history a little bit more and be a little bit more honest, if we’re going to disrupt it. We do that by looking at what actually took place during the slave trade, which is very complicated and very complex.

There were a lot of different tensions, there were a lot of different relationships between African people that show us that it wasn’t just as simple as many would hope to make it. I think that people give European slave traders too much credit. They were not as efficient as I think some narratives might make them, and not as intelligent as many narratives might make them. So I bring up the example in the text of Liberia and the formation of Liberia. I talked briefly about the fact that formerly enslaved African people went back to the continent and engaged in some heinous, very disturbing things that included using the backing of the US state to acquire land, to force servitude, and to expand a settler process on the continent, in the name of forming a Black nation. You can’t separate that history from this idea of trying to form a Black nation now and say that it doesn’t matter, it doesn’t compare. There’s something there and that history that has to be looked at closely and observed in terms of what it means for Black capitalism, but also what it means in terms of Black nationalism. So those are things that I like to bring up because it’s these overlooked aspects of history that I feel would help people challenge this automatic response of just embracing what conventional leftism has told us, and conventional radicalism has told us is the way to go.

TFSR: That probably comes back to the quotation from Gilroy, I mean, even just proclaiming that innocence in a way evacuates, empties people out of the way that they actually operate in the world, which is not just one thing or the other.

W: And something that it does, too, that’s important to note, is that it actually, in my opinion, takes away from looking at Black people as people. It’s like when you try to create this myth of this essential innocence and make Black people into this uncomplicated homogenous group, you’re actually doing something that is really disrespectful to Black people. That’s an important takeaway here: by trying to make Black America into this exceptional group that is innocent and incapable of doing anything harmful, you’re actually feeding into another sort of violence and disturbing rhetoric against Black people.

TFSR: Right. Because in the end, that’s not even super different than some of the racist stereotypes that have been imposed upon Black people historically in the US. This might actually be a good place to pivot to this question I had about popular culture because you talk about celebrity and stuff, but I just wonder what your thoughts on how we relate to pop culture, because it clearly is inspirational to a lot of us, but it’s also super captured by the structures of capitalism, individual gain, there’s a hierarchy. You made a really amazing playlist that goes along with your book, for example, there’s a lot of political music on there, too. But I’m just wondering, how do we engage with this cultural production from an anarchist lens. The history of American pop culture is a history of a lot of theft of Black cultural production. But it’s also a place that historically, I think, Black improvement has been relegated to and the way that white consumers relate to it is another version of this flattening out, which you see also in writing and stuff. James Baldwin talks about this a lot. So I just wonder what your general thoughts are on pop culture, because it’s there, it’s inspiring, and it also has problems?

W: I think the relationship that we have with celebrity culture is also tied to the critique I make of Black capitalism and Black capitalistic rationale. So much of the value that people put on celebrities has to do with the wealth that they’ve acquired, the visibility that they’ve acquired, and these forms of capital that people seek out in social ways. When we’re thinking about celebrity culture and what fame means, a lot of times that feeds into this disturbing interruption that occurs within our movements, because activists end up becoming famous organizers, they become celebrities. That ends up being a distraction and a counter-revolutionary seed in our movements because it becomes more about what this one famous person, who’s a famous activist has to say and what they think because they are the leader.

Black anarchism, I think has a lot of really great insights, obviously, with regard to the historical critiques around hierarchy, and vanguardism, and the way that those things are problematic in our movements. That’s one aspect of it. But there’s also the way that people who are famous for other things, be it music or sports or whatever entertainment, the way that those people are viewed automatically as leadership and the Black vanguard or as someone who has some expertise on activism just because they’re famous. So fame also generates this idea that there’s an inherent intelligence and understanding that comes with the ability to accumulate. So it’s to say that this person is famous, so they must know what needs to be done, they must know what we should do, we should go to them. You end up having these celebrities who are commenting on things that they know nothing about, that they have no understanding of, with regard to movements and politics. It’s really absurd and really dangerous for our movements because you end up having people following the words and the direction of someone just because they’re famous, when they have no clue what should be done, no clue what’s happening on the ground, what is happening in communities.

So, Black autonomous radicalism, Black anarchism helps us to see that the people who know what needs to be happening are the people who are in those conditions, the people who are actually in their communities. It’s not just about the famous activist, it is not just about the celebrity. It’s not just about the famous revolutionary. That’s another point I try to make the text because I think that a lot of leftists would have a critique of a celebrity in “stan” culture and these cultish relationships that people have with certain celebrities, but they have those sorts of relationships with dead revolutionaries and people who they’ve turned into saints, and people who they’ve turned into infallible politicians and leaders of the past. They look at these people, and they have a fandom of their own, with regard to the way that they view history, and they treat their favorite historical figures as perfect, flawless characters that are unquestioned because of their historical fame and their noteworthiness with regard to revolutions of the past and efforts and fights of the past, that also escape critique because of their fame and the way that we regard them in this fantastical, mythological way.

TFSR: It makes me think, if we relegate our politics to the politics of representation, which was a huge response by corporations to the uprisings of last year, George Floyd uprisings to be Netflix Bookmarks series, we really get politics to that. Then also the representation that comes from having Black artists, Black actors, Black creators of culture be the spokespeople, like you said, ends up reifying that monolithic version of the race that is what the struggle is to destroy, right? By saying that someone could speak for a whole people, that are identified by this power structure as belonging together. So representation gets talked about a lot as a route of freedom, but it ends up being such a trap so often. As a teacher, I always get caught up with people who really stick to these things. Megan Thee Stallion is a feminist or something like that. Because we have such a simplified view of what it means to be political, it is just doing some basic form of empowerment.

W: I hope that people will understand that I’m not saying that a famous person can’t contribute to a movement. I’m also not saying that a person who’s a celebrity has nothing to give or nothing to offer or can’t know what’s going on or have an informed analysis. That’s not the case. I bring up Paul Robeson as a historical example of someone to look to that actually had a lot of amazing things to contribute to movements and had done a lot of work that is actually really impactful historically. But rather than thinking that fame is something that we should use to try to build movements, I’m saying that it’s actually a problem because it feeds into a lot of hierarchical arrangements, and a lot of disturbing notions of leadership and vanguardism, that we need to move away from, in my opinion. After all, I don’t think that we should be looking for some elite to guide us, be it a revolutionary elite, be it an entertainment elite. I think that what’s happening amongst everyday people who are self-organizing, who are building autonomy, and who know their own unique conditions, that is who needs to be focused on. The actual people doing the work in their own communities, in their own neighborhoods, and understanding their own conditions better than anyone else, would try to tell them that they should be understood under the guise of whatever ideology they might do that.

TFSR: One thing I hadn’t really thought about a lot, but I heard you saying is that it also connects to the ideology of capitalism, that there’s a meritocracy, like the people who we know, we’ve heard about are there because they deserve to be there rather than whatever luck brought them there. I think that’s really important to keep in mind also. Whatever becomes super mainstream and popular isn’t going to give us the full story. If it’s so popular, it can totally be a threat anyway. In that line, I want to go to the way that you talk about the legacies of Black freedom movements of the mid 20th century, and how they’ve been rewritten into a nationalist story, and I’m gonna quote you say that “it’s been made into a singular struggle with one line of thinking”, and that you call a state project that attempts to give Black people a stake in the violence of the US. So what is called Black history becomes everyone’s story. Then a source of pride for the US, not shame, for example. I was just wondering about that process and how it affects Black people, Black radicals differently than white radicals who are trying to struggle against racial capitalism and the state, too.

W: The way that this plays out, and has played out for some time now, historically, is that the state is able to absorb the Black struggle, by making it into something that is a necessary gear or mechanism to make it better. What I mean by that is I’m saying that the way the state has absorbed and taken the story, for example, of the civil rights movement, and made it about an overarching effort to just reform, the intention, and the direction of the US state, that’s something that has completely been normalized. That’s what we get in education in school and grade school, we’re taught that from the earliest moments that we enter into the education system. We look at that and see how the state is using Black history to maintain itself by saying that Black people have only ever wanted to make the state more efficient and more inclusive and better, rather than looking at the whole of Black History, where we can come into a much deeper understanding that that’s not the case.

One of the examples that I bring up in the texts, as I talk about Lucy Parsons, again, a formerly enslaved Black woman, who’s an anarchist, and she’s arguing against voting at a time where she doesn’t even have the right to vote. She couldn’t even vote and she said, this is worthless. She couldn’t even do it. You look at an example like that and you say, “That’s amazing for Lucy to have had that insight into the symbolism and the emptiness of US electoral politics at a time when she couldn’t even legally engage in it. That history really pushes against this idea that Black people were just a single movement, Black radicalism was just a single movement full of people just trying to fight to be included and treated better by the state. That’s not the case. So, we obviously see what this can turn into when people lean into that reasoning. You know, we have things like the 1619 Project, which said Black people made the US a democracy or something like that. But it’s not a democracy, it is not a project that is even doing what it claims to be doing in terms of, again, for example, voting. We still don’t have a guaranteed right to be able to cast votes as Black people in the United States. To say that Black people made the US a democracy and to feed into this idea of a more inclusive US project is actually doing a disservice to our movements by saying that the state is something that is redeemable, and that can be fixed if we just keep pushing and trying to make it better.

Now, whether people want to talk about it or not, that’s happening also from the left. And when we look at it in a more global context, what a lot of the politics that we see from many versions of state socialism are saying is that we need to just have a better state and that there are states that we need to be trying to be more like, because if we’re able to reform the state to a socialist economy, that’s going to solve all of our problems. Then, traditionally, obviously, there’s been a line that the state will wither away, and then we’ll have a stateless society, and that’ll be communism. But again, when we’re truthful about history, and we see what has happened historically with state socialist projects, you cannot just lay blame for everything going wrong at the hands of the imperialists and empire. There have also been betrayals, there’s also been atrocity, there’s also been corruption, there’s also been a lot of horrible things that have happened, that have contributed to why those projects haven’t done and achieved what we’ve been told by the conventional leftist narrative that what we’ve been told that they were supposed to do. So, when we look at those things in a much deeper way, we can begin to actually start to create and craft movements that think beyond the state, that think beyond trying to reform and fix all of these really dangerous structures that people are trying to wrestle with and lay claim to. In the context of us nationalism, so much of that takes place in really insidious ways, whether it’s the classroom, the museum, or television, popular culture, we are always being told that we can lay claim and reform what’s oppressing us and what’s killing us. I’m trying to write against that idea across the entire spectrum and say that these things are not for us. They’re not going to free us. People have already been trying to do this for long enough for us to say, “this is not working” and for us to do something that transcends the left and all of our ideas of movement and left radicalism entirely and historically.

TFSR: One of the convenient things about the narrative that we’re talking about that makes it something that’s over, which obviously, as you point out, contradicts the material reality of people’s existence, that struggle for freedom is over. Or even if it was just limited to voting, while the Supreme Court or whatever could say, “there’s no longer a threat to Black people voting”, that is clearly not true.

W: One thing I would add to that, too, is that for me to say what I just said, for example, about state socialism and how the promises of liberation are not completely achieved by just transitioning to a socialist economy. What I’m saying there is, again, similar to looking at the history of the civil rights movement and of reform and of legislative efforts. Because what is true is that there have been gains that have been made, of course, with state socialism. But there have also been gains that have been made through reformism and through some of the liberal efforts of liberal activists in the civil rights movement. I’m not saying that reform has never achieved anything. But what I’m saying is that it’s not enough. I’m not saying it’s never done anything. I’m not saying that Black nationalism has never done anything. I’m not saying the state socialism has never done anything. I know that they have, I recognize it much. But what I’m saying is, we have to be honest about the limitation when we see, the patterns that have occurred historically and push for something greater. That’s the point that I’m trying to make. So you say these things and people get defensive because they know about gains that have been made. But I’m saying let’s push for something much greater than the table scraps of liberalism. Let’s push for something much greater than the limitations and the violence of the state.

TFSR: Yeah, whether it’s from a performance perspective, or the authoritarian left, or the statist left, there’s this “realism” that gets invoked against our aspirations of freedom. But what you say in the book is that there have been some gains, right? I like the way you say “liberalism’s table scraps”, but they’ve also been gains that plug us in further to this killing system that’s continuing to kill at the same time.

W: Exactly. Because when you make those gains be a complete totality of everything, and when you overemphasize them to such an extent, you end up feeding into the system in such a way that you start working to preserve the system rather than exceed it and go beyond it. So when you overemphasize what has been done, you might start to lose sight of what could be done. You can look at the history of the Civil Rights Movement, or the Black Power movement, or any movement and act like it was perfect, and then just that it just needs to be mimicked. Because it’s not good to start getting caught up in this idea that that was it, that’s what we need to do again. Because when you’re doing that again, and again, and again, you’re not working to break free of it.

TFSR: Yeah. I think that was beautifully said. One thought that came up, a connection that I hadn’t made before. There’s something that I think is a really important connection that you make in the book is that you take a look at the great migration historically as a continuation of a diaspora that’s ongoing and connected to gentrification. I’m thinking about this also in relation to the statist leftists who can’t deal with the fact of stateless people, if their solution is the state. You use the migrant status of Black people within the US and also around the world as a point of solidarity, and you even talk about your own radicalization through migrant defense work. So I wonder if you want to talk a little bit about your reading of the great migration, because I think it’s something that maybe needs to be spoken about more, and also how you see that fitting into the current moment and in places of solidarity in the ways that the state is threatening most vulnerable people.

W: Yeah, the interesting thing is that that actually played a lot into my interest in anarchism, too. I was really frustrated with the left, but I also was thinking about anarchism because I was doing this organizing work that made me think a lot about citizenship and the state. In the immigrant rights movement, I’ve gotten involved because I understood that I was not a citizen, I was taught that growing up, my parents told me, you’re not just a second class citizen, you’re really not considered a citizen at all. I internalized that in a way growing up that became a part of my politics now and my understanding and thinking around statelessness, and the ways that Black people experience it across the Americas. With regard to all of that, I know that in the immigrant rights movement, there is a lot of subtle and overt racism against Black people. Black people are not the face of the immigrant rights movement. Despite experiencing disproportionate rates of deportation and incarceration, Black people are not seen as undocumented, or immigrants, or as migrants. What that ends up doing is it takes away from a type of solidarity and a type of struggle that could be built, it actually undermines that movement significantly. I used to try to point that out in that movement, where people didn’t really have a lot of understanding of why I was participating. I was trying to find a language to explain this back then. But it didn’t always come out the way that I can express it now, because I had to take a lot of time to think and develop the understanding that I now can claim. But you hear people talk about migration struggles, and they totally neglect the Great Migration.

To be more specific, they neglect the Great Migrations, there was more than one that has occurred with regard to Black America, forced and otherwise. They’re all forced in the sense that I’m talking about migrations of Black people who had to leave because maybe they got priced out or gentrification happened now. And historically, you had migrations during enslavement, whereby people were forced to move en masse to other places in the country because of the demand of the slave-holding class and what their desires were for agricultural production. When you look at that history and pay attention to all of the times that Black people have had to move and have been pushed out of places and forced around this country, it creates a pretty stunning example of what we can see on a global scale that’s happening domestically, which is there is no real place to run to find this absolute safe haven and asylum that we can lay claim to that’s going to protect us from state violence.

When you bring that into the history of Black anarchism, you see someone like Lorenzo, who’s fleeing to other countries, looking for that asylum and not finding it. Lorenzo’s story is one of many. I highlight his specifically because I’m talking about Black anarchism. But there have been plenty of other times where Black people have historically gone to other countries looking for liberation, looking for freedom, and did not find them, including under state socialism. That’s something that’s happened both domestically and internationally. I’m trying to draw that connection there. Obviously, domestically, we’re talking about under the oppression of the US state. But then when you start thinking outside of the US state, there’s a discussion to be had about what Black people and migration tell us about the state generally, here within the US context, but also outside of the US. There’s something there that needs to be unpacked very much, needs to be observed deeply and internalized.

TFSR: I appreciate it in the book that you draw the connection that those conditions that force Black migration within the United States aren’t different in kind that forces the other migrations around the globe, whether it’s Black people or not, but it does include Black people, and, as you rightly point out, that’s often overlooked. But building on that idea that you said came from your parents, too, in terms of your relationship to citizenship as a Black person in the US. That’s something that is going back to your work with Zoé Samudzi, the idea of Black and anarchy, that being Black in the US positions someone into being potentially this internal threat to the coherence of the state, that doesn’t necessarily translate into radical organizing or radical consciousness.

But one of the things that I see you really working on in the book is how do you move from that space of being potentially a threat by definition from the state to actually working towards generalizing that ungovernability or whatever a process of that radicalization is; how do we get people to see those conditions and then politicize their actions. You frame this also just in terms of the Black Panther survival programs, which weren’t just like feeding people, but also politicizing them. So I was just wondering if you could talk a little bit about what insight you’ve gained about individual radicalization from a position of blackness, and also how to frame the survival programs that you talked about Black people having been doing historically for generations and centuries even, but like how to frame those as explicitly antithetical to the state.

W: I think that one of the best things that we can do is discourage people from positively identifying with the US project. We can do that by illustrating all of the different times that state violence has targeted Black people historically. We can do that by talking about statelessness. We can do that by talking about how Black people have been positioned as inherently seditious, inherently “alien”, or inherently criminal. Those sorts of realizations help us highlight that this is not something that is going to be fixed through reformism. When we were writing The Anarchism of Blackness and talking about the way that Black people have had to work and think outside of the state and engage in anarchistic practices without laying claim to anarchism as a set of policies, necessarily, what we are saying there is that highlighting those examples historically and talking about how they occur repeatedly throughout history, even today, that is telling us and that is informing us about what the state actually is and what it means with regard to Black people. So rather than trying to reform it, or seize it and lay claim to it and reform it, we’re discussing what we can actually do to delegitimize it in our minds and move away from trying to make it ours or make it better or make it more efficient. It’s important to advocate for that, in my opinion. Because if you get caught up in this idea that you can actually reform the state, what ends up happening is you get this overarching patriotism, that creeps in there and starts encouraging people to try to find value in what it is they’re putting efforts towards reforming and trying to fix. If you’re doing all that work, you might start saying, “Well, this is something that’s redeemable and it’s something that can just be adjusted.”

That’s one of the things I think is really important for anarchists to challenge specifically because you hear a lot of conversations among anarchists and around mutual aid, you hear a lot of people saying, “I’m not trying to let the state off the hook, or I’m not trying to fill in the gaps for what the state should be doing.” But I think that what we were trying to get at back then with The Anarchism of Blackness was saying the state is not on the hook. The state is not malfunctioning, it’s not doing something wrong when it commits state violence against us, that is a part of its core function. It has a monopoly on violence. It creates a system of haves and have-nots. It has a ruling class, it has core intentions that tell it to do what it’s doing, that give it instruction and give it life through doing those things. So rather than trying to fix them, we should actually be encouraging people to remove ourselves from the idea that it has something for us in it that we just haven’t discovered yet.

TFSR: Do you have any thoughts on how to make our mutual aid projects not co-optable? Because they do fill in the gaps in terms of making people survive and I’m thinking in disaster relief, and particularly in the long COVID period where there’s been a lot of survival programs put in place by people, and they may be done by anarchists, but I don’t necessarily see how they’re a threat. A lot of disaster relief work around hurricanes and stuff could be claimed by the state after the fact. I mean, that’s something you talked about in the book, that that’s something that we need to do. I would be interested to hear your thoughts on that.

W: Well, I think that one of the most important things to observe is the history of revolutionary intercommunalism of the Black Panther Party. That’s one of the reasons I’m bringing that up in the text. And that’s where we get survival programs. That’s where that comes in. So survival programs and mutual aid are obviously distinct, and they have different meanings. I’m not trying to conflate the two. But one thing I’ve been saying when I talk about this book is that these are both things that work. They can complement one another. Because of people’s dedication to dogma, to ideology, to doctrine, they look past things that could work to their benefit. So the intercommunalism of the Panthers and the survival program is something that offers a lot, a lot, a lot of valuable, good history, good organizing, good work that can be done to actually be much more effective now. I don’t think that people have a real deep understanding of what it was that the Panthers were doing with intercommunalism and what the survival program was.

What needs to be done is going to be specific. First and foremost, I want to say that it’s going to be specific to every community, and I’m not going to try to be a person that is doing exactly what I tried to speak against, saying that there’s a one-size-fits-all approach that is gonna save everybody, I’m not going to talk like that, or at least I want to try to avoid talking like that. But one of the things that we can see with the survival program, for example, was that Panthers were creating a systemic approach to meeting the material needs of people and communities across the country and doing things that were absolutely necessary to sustain everyday life for Black people. They were not just doing it to just be doing it. That’s an important thing to note there. Because you can have a program, or you can have a mutual aid group, and just give out food, or give out clothes or do whatever the case may be. But if you are not politicizing that word, undermining capitalism, talking about state violence, and rejecting and fighting back against it while you’re doing that work, and through that work, then that takes away from what you’re doing. If I give somebody some groceries, and say, “Hey, here’s some groceries, I know that you need some food,” it is not the same as giving somebody some groceries that have some propaganda in there, that say, “I’m giving you these groceries because of this capitalist system creating a problem where you don’t have access to them in the first place oppressing you.” Those are two completely different things.

So, you can be giving someone groceries every week. But if you’re giving groceries with that intention, and with the political education, and the radical information you can distribute with it, it’s a much different thing. These efforts have to be politicized and be radical in a way that actually is doing the work, which makes it a threat. The Panthers were targeted because their work was a threat. What is going to make our work threatening, what is going to make us ungovernable, to quote Lorenzo, a lot of that has to do with the political intention to actually undermine the state and to undermine the efforts of the state to maintain power. So, you can’t just do it just to be doing it. There has to be that intention behind it. I think that that’s one of the most important things, and when you look at different Black anarchist approaches, one of the things that’s going to come up is “Okay, if everybody does start doing it with that intention, where do we go from there?” Again, that’s going to be a different answer depending on who you’re talking to, or depending on who you’re reading in terms of Black anarchists historically. But if you talk to somebody like Lorenzo, Lorenzo is going to talk about dual power, he’s gonna talk about building dual power.

Again, that takes us back into the history of Black anarchism drawing from that which informed it, but that which it also critiques. So that dual power that’s coming from Lenin, and I will tell you right now, Lorenzo has plenty of criticism for Lenin. But he’s drawing from dual power. You can talk about Pierre-Joseph Proudhon outlining dual power before Lenin. You can keep going back with the history there, that it’s more complicated, but Lorenzo’s conception of dual power, he’s drawing from Lenin and talking about building a complete economy, a complete network that is taking these efforts to actually counter the state and making them so effective, that it is actually posing as a real challenge because it’s connected. It’s not just happening on these individual bases, sprinkled throughout the country and isolated. It’s being connected in a way that begins to actually pose a challenge to power. That has to happen globally, too, when we’re thinking about this, this isn’t just about what’s happening within US borders.

TFSR: And that’s how you pull on Huey Newton’s intercommunalism as a replacement for internationalist thinking as a way of linking struggle without that nationalist idea. I think that’s really important. I’m grateful to you for teaching me about that. I’m going to characterize this as a white leftist utopian idea that defers revolution to another time, but also it’s always thinking about catastrophe is impending, not here yet. But when you listen to the Black anarchists, indigenous anarchists, there’s this awareness that we’re in the middle of it, right? It’s not it’s not about to happen. It’s been happening. You say in the book that the race war isn’t coming, we’re not just looking at white supremacists and Nazis preparing for the race war, it’s here through the state. So, I’m wondering if acknowledging that survival-pending revolution doesn’t mean the revolution is always to come, but it means that we’re in the midst of it right now, maybe. How does that help us reframe these dual powers, mutual aid, survival programs as more effective at the moment rather than preparatory to something that’s going to come?

W: I’d say, if we’re being honest about conditions and what has to happen, there’s no real choice other than to be building these programs. Because if we don’t, people are going to perish and people are going to suffer. If we’re honest about the fact that the state is not for us, it’s not serving us, it’s not benefiting us, then there’s a core truth that comes with that, that this system which is ruling over our everyday lives is a part of the crisis that people seem to have this cinematic idea of. It is a part of this crisis at the current moment. It’s not something that is a destination that’s far away. It’s something that is here now. It’s connected to our everyday lives in this present moment.

So, rather than trying to portray it as something that is this end-of-the-world apocalyptic moment, we have to look at what’s occurring on a day-to-day basis. I would encourage people to read Professor Bedour Alagraa’s work because her writing on catastrophe has been pretty influential around my thinking here. But it’s not something that we can just look at as a final event that’s going to take place and just fall on our heads. It’s something that’s playing out day to day. And for us to actually work against it and to fight these systems that are dropping terror on our lives regularly, we have to recognize as much and try to undermine and work against this repetition that is playing out in this destructive way, rather than treating things as if they are going to play out in this cinematic film-like fantasy way that there’s just this one explosive thing that’s going to happen. A lot of the history and a lot of the events that we think of as a part of that film-like fantasy are things that have already occurred before and are things that are going to occur much sooner than would happen in that play in our heads.

TFSR: The subtitle of the book is Black Anarchism and Abolition, and one way you define abolition is that it is one step within a larger project of the revolution. How you’re talking about this makes me think that it changes the timeline of revolution, like abolition is this thing that we’re doing right now within this larger horizon. I wonder if you want to talk about how you see abolition, and how it relates to a Black anarchist project, too, because those words get linked, but they’re also seem to be distinct, right?

W: When I was talking about abolition, I was talking about it because, obviously, abolition became much more widely discussed in a very quick amount of time. I wanted to take abolition beyond the state for more people. Because I think that what abolition meant to a lot of people when it became so much more widely discussed and embraced, the way that it did during the uprisings of 2020, I think what abolition meant for a lot of people was no more police and that’s it. I was trying to complicate it in this text by saying that the police are just one aspect of state violence, they are not the entirety of it. Ultimately, if you want to get rid of state violence, you need to get rid of the state. Black anarchism is already been having that conversation for a long time now. So I was just trying to bring abolition to that point for some people who may not have been there yet.

TFSR: It’s so important, I think always to include the state in our project of abolition, not even just police and prisons because they all uphold each other in a way.

W: Even if you were to get rid of the police, that’s just one form of policing. That’s just one form of systematic violence that the state uses to inflict terror on people domestically and globally.

TFSR: Exactly. One thing that comes up for me is going back to migration, diaspora, and the relationship of diaspora and indigeneity. I’m Jewish, I am from a diaspora position, and specifically, as a Jewish person I’m against Zionism as the solution to diaspora or something, because it’s another violent settler state, a racist settler state. But I’m also like a settler in the US. So I was just wondering, from a Black anarchist perspective, how you might relate the conditions of diaspora and the support of indigenous struggle, without turning them into some argument between the two, which I see also happening sometimes. Because a distinction that has been drawn between the conditions of blackness and conditions of indigenous people in the US is like landlessness and stolen land or something like that. I’m just wondering what you think are connections of support and solidarity between a Black anarchist perspective and support of indigenous struggles in the US and worldwide? I was framing it through a question of diaspora because diaspora and indigeneity could be seen as some oppositional position. If it doesn’t really make sense to you, that’s fine. I’m struggling a little bit with how to articulate it, it was something I’m interested in.

W: There’s this thing that happens that people don’t see Black people as indigenous people. In a way, that parallels what I was describing with the way that Black people are not seen as migrants or immigrants. I think to put them in proper conversation, you just have to recognize that Black people can occupy that category and do occupy that category, and to have a more complete understanding of indigeneity, rather than trying to make blackness and indigeneity mutually exclusive. So, when I’m talking about bringing a more full and complete understanding to Black people and blackness and migration, then what happens is you start doing the work of getting away from undermining what could be a stronger movement when you have that more comprehensive understanding of all of the intricacies that can take place under that term. In the same way, I was talking about how the immigrant rights movement undermines itself by excluding and having racism against Black people, rather than seeking to be included and to diversify, just being honest about what is actually taking place. It’s not just about including me in this movement and making me a part of it. I’ll have representation rather than saying, “Why is this movement not including and why is it not recognizing this,” and then trying to do better and go beyond and push for more. I think that the same thing could happen for sure with indigenous and anarchisms, rather than having this conflict around inclusion.

TFSR: The other thing that I would love to hear you talk about is the title of your book because I think it’s a really beautiful, evocative title. You’re critical of the nation, but in the title and in your writing, there’s this idea of a nation beyond the state, and map, too, has been a tool of colonialism, but also holds some mystery. I’m just wondering what you’re saying with the title and what your inspiration here and how that phrase “the nation on no map” frames blackness in relation to the state?

W: The title of the book comes from Gwendolyn Brooks’s poem about the gang that was once called the Blackstone Rangers. She has this line in the poem where she says “their country as a nation on no map.” When I first read that poem, it really stuck out to me, it was so beautiful, the way that she constructed that. It was something that I included in As Black As Resistance when we’re talking about the complexities of gangs in that text. Part of what’s being said with the title is that there is an acknowledgment of that statelessness that is there and that phrasing “the nation on no map”, but there’s also another thing that I’m trying to do, which is to say, what if we’re not only a nation on no map, what if we’re not a nation? And what if we’re not on a map? Because we know that those things are not for us. It’s really about acknowledging our position but letting that lead to more questions about why that position is what it is in the first place. So I’m not trying to advocate for nationhood in any way, I’m actually questioning it with that title. So I appreciate Gwendolyn Brooks’ poem as well because I think that gangs and organizations that formed on the streets have a lot to say and form a lot of my thinking about how things could potentially look in the future in terms of the way conflict I feel is going to play out in this country. I think that a lot of the left ignores and doesn’t recognize gangs, and doesn’t think and try to approach gangs in the way that needs to happen. But there’s a lot of revolutionary history there. So much of this is about overlooked history. There’s a lot of evolutionary history there that has to be acknowledged, and I wasn’t trying to go back down that path, because I felt like it was already covered a lot in As Black As Resistance. But I was trying to bring back that thread.

TFSR: I think that’s super important to look at gangs and how it gets overlooked. Thanks for breaking that down. In the book, you also have included photographs, and I just wonder if you can talk about how you see them interacting with the text. They are beautiful and haunting clearly. How you chose them or what their role is in that text?

W: Those are just all my photos. I took those photos over years. There were just a lot of different moments, when I was writing this text, that I saw something and I took a photo, and I was writing the text and thinking about how those photos and what I was taking an image of how it relates. For example, somewhere within the chapter where I’m talking about the narrative around kings and queens and the mythology and the way that history is mythologized to make Black people into all descendants of African nobility, I thought about that with regard to a Slave Rebellion Reenactment that I attended in Louisiana, and I took a picture of one of the re-enactors on his horse. I put it in that chapter because I think that is absolutely connected to what I’m saying. I wrote an essay about that, that also exists on Hyperallergic. I wrote that, but I thought about it and its connection in the sense that the way that I was seeing this idea that by glorifying this former slave rebellion, it will restore a certain pride and a certain revolutionary spirit in Black people. It made me wonder about the connections between the past and what we tried to communicate through emphasizing certain history. I thought that it was really interesting to witness that at the Slave Rebellion Reenactment that I went to. So I put that picture there, just because I thought it was connected. I didn’t go into the detail, obviously, that I went into just now, but it’s just something that I was thinking about when I was there.

Many of the photos in that text… I talk about bombings, I talk about Dynamite Hill, I’m from Birmingham, so I took a picture of Angela Davis’s childhood home on Dynamite Hill in Birmingham, and also took a picture of Bethel Baptist Church in Birmingham, which was also subject to that violence. They’re just there to illustrate connections. But they’re also there because I like to include as much imagery with my writing as possible. I try to be very thoughtful about images, whether it’s an essay or a book, there are no images in As Black As Resistance. But I definitely will try to put images wherever I can, because I think that they make it easier to read. I think that people like to look at things and see images while they’re reading. I think that it also helps try to take away from this idea that the type of writing that I’m doing has to be really plain and not interactive. So I’m trying to make it more fun to read something that’s not necessarily a fun subject, if that makes sense. Maybe fun isn’t the right word, but at least just make it more interactive for people.

TFSR: I totally get what you’re saying. I really appreciate you unpacking that particular connection. But it’s almost an invitation to the reader. Because it sparks your imagination and be like “Well, what is this picture? What is it doing here? How does it relate to the text?” It invites interactive reading.

W: I write about photography, a decent amount. I have multiple essays out there in the world about photography that I’ve done with Hyperallergic and the British Journal of Photography. So photography is really important to me as an art form, but also as something that can be violent, and used for really horrible and disturbing purposes. So I think about photography a lot. It’s always something like music, it is just a big part of my life and my work and I try to interact with it whenever I’m doing these things.

TFSR: You’ve entertained a lot of questions, and I really appreciate you taking the time to talk to me and think about all this stuff and present some of the ideas from your book to the listeners. Is there anything else that you’d want to talk about or cover that we didn’t get a chance to?

W: Not at the moment, just want to say thank you for this interview and for reading the book. Thanks to anybody that’s listening for listening or reading the book or thinking about reading the book. I’m really grateful for all of it. Everyone that’s listening, be safe and be good in your community and try to do what you can, and solidarity.

TFSR: I really appreciate your thinking and your work and I think it’s a huge contribution. Thank you for taking the time and we’ll include in the show too, how people can connect with your work and you if you want.

W: I appreciate that.