A History of Black Bloc, plus Bad News!

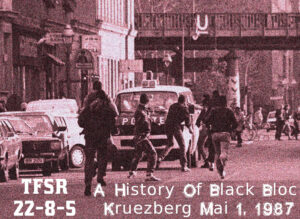

First up, we’re sharing a blast from the past blast from the past, an interview that we conducted in 2013 via our comrades from A-Radio Berlin with a participant in the autonomous anti-capitalist street movement in Germany in the latter half of the 20th century known as Autonomen. Specifically, the guest speaks about the context of anonymous street actions during May Day of 1987 in the district of then-West Berlin known as Kreuzberg and about the tactic that became known as Black Bloc. Apologies for the audio quality of this portion.

- Transcripts

- PDF (Unimposed)

- Zine (Imposed PDF)

Then, you’ll be hearing portions of the May 2022 episode of Bad News: Angry Voices From Around The World by the A-Radio Network, of which the already-mentioned Berlin crew is also a member. You’ll hear:

- comrades from Free Social Radio 1431AM in Thessaloniki, Greece with some updates from that country.

- Then, friends at Črna luknja in Lubjlana, Slovenia, shares an interview with members of the autonomous social center in Trieste known as Germinal on the 10th anniversary of that space.

- Finally, you’ll hear A-Radio Vienna sharing the call-out for the 2022 June 11th Day of Solidarity with Marius Mason and All Long-Term Anarchist Prisoners. You can find more on June 11th at June11.NoBlogs.Org

. … . ..

Featured Tracks:

- Mainzerstraßenlied by Quetschenpaua from Terror Penguin Music (lyrics)

- No Borders No Nation by Kronstadt from Antipoder

. … . ..

Transcriptions

Kreuzberg 1987

Anonymous: I’d like to say right at the beginning that I will (and can only) describe this complex political context from my own perspective.

TFSR: For the American audience, can you briefly describe the partitioning up of Germany and of Berlin after the 2nd World War? What parties ruled and in what places?

Anonymous: After WWII, Germany was split into East and West Germany, corresponding to the sectors of the victorious allied powers: the Soviet Union, Great Britain, the US and France. It was the case at the time that the German Democratic Republic (the GDR) was under Soviet control and the later Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) was controlled by the three Western powers. The capital city of the GDR was East Berlin but the capital city of West Germany was not West Berlin, which held a special status, but rather Bonn, a small city in West Germany

It’s important to know that there were border controls, there was the wall around West Berlin and there were strict border controls when you wanted or had to enter the GDR or if you were trying to get from West Berlin to the FRG or vice versa. There were special highways for this purpose. Going in the direction of the GDR, the bureaucracy and controls were stricter.

As far as political parties go, in the GDR the Socialist Unity Party (SED) was in power all the way until reunification, which can be understood as an annexation of the GDR by the FRG. And in the FRG there were changing coalitions between two large bourgeois parties and one small one, which were in power in different constellations. In the 80s a new, environmentalist and kind of leftist party joined the mix, but it was fairly small.

TFSR: What city were you from and/or based out of as an activist? What brought you into activism and what general sorts of activities did you participate in?

Anonymous: I come from West Germany but I’ve been in West Berlin since 1980 and was politicized and active in the squatters’ movement. But really only in the 90s, since in the 80s I was still a bit too young to really actively take part in the squatters’ movement, which began in 1980. I could also mention the anti-nuclear movement. As a teenager it was really in back then to hang out in the left alternative environmentalist scene, the leftist urban guerillas RAF in Germany were really in fashion and you saw the abbreviation everywhere. The circle a, the anarchy sign, was also somehow cool. That was kind of the ambience of my political socialization as a teenager.

I also took part in demos in West Berlin and West Germany but not only against nuclear power and so on but also against state visits by American presidents or, for example, the Secretary of State Alexander Haig. What I did in everyday life was neighborhood organizing, infoshops, hanging out in the Kreuzberg subculture, taking part in radical leftist campaigns, squatting. That’s me.

TFSR: Can you talk about the tendency known as Autonomen in Germany? What were its guiding principles and what sort of activities fit under that title?

Anonymous: I can say what it was like from the beginning of the 80s, before that there wasn’t really this concept of the Autonomists, anyway. Later I will say more to that, though. As far as the principles go, to shortly list some of the important ideas:

Consensus based decision making / deconstructing dominance, not denying it / internationalism: act local, think global / no representative politics but rather self-organization, starting with yourself instead of saying moralistically that “we have to struggle to win this and that for the people” / trust through social contact rather than through participation in an organization / rejecting and actively questioning bourgeois ways of thinking and living / building up alternatives and living for oneself instead of just saying “at some point the revolution will happen and then everything will be great” / self-determined choice of means in activism beyond legality: “legal, illegal, scheißegal” which means basically “Legal, illegal, fuck it” / using the experiences of 68 / opposition to organization / an anti-state position, antinationalistic, undogmatic, incalculable

As far as activism, we talked about it a lot at the time, and there was a consensus that non-participants should not be endangered. There were, of course, the two gray areas of Nazis and cops, though. There were also long discussions about where the border is, but the important thing was: no non-participants should be harmed.

Some other important ideas were:

Pushing the boundaries of the state, testing out how much leeway there was there and trying to hold on to whatever we gained / intervening in social struggles and problems: class struggle, sexism, racism, anti-semitism, etc.

We also took part in a lot of things that weren’t specifically autonomous: normal demos, sitting blockades or vigils, distributing flyers, organizing events or – as a realization of our own political aspirations – creating work collectives and communes, also in the countryside.

The things that were specifically autonomous, which other people tended not to do and it was rare that others did with us and so, as far as participation goes, stayed small were: squatting houses / having unpermitted demonstrations / so-called ‘scherbendemos’ where all the stores and the shop windows of companies, which were closely bound up with the capitalist or state system, were destroyed: banks, big chains. The whole thing was limited to the previously envisioned goals. Making actions out of legal demonstrations, for example attacking cops or spraypainting on the walls during a demonstration, or throwing eggs filled with paint, as a unified block during permitted demonstrations / clandestine acts of sabotage, such as setting fire to company cars or infrastructure like electricity poles, train tracks, in the case of nuclear waste transports or before nazi demonstrations / marking or outing Nazis and political representatives, finding their meeting points and where they live and marking those places, whether with paint balls or with public but unpermitted actions, where things also happened during the day, so-called half public actions, where people tried to show up somewhere with a lot of people that had organized amongst themselves and to give a speech, distribute flyers, spray paint, make noise, loot, throw foul smelling liquids, when, for example, a luxury restaurant or department store opened, hang banners, go into institutions or company headquarters or offices all dressed up and do a bunch of bullshit, create confusion in order to raise awareness in a campaign.

Organizing camps for and by radical leftist, for example on the theme of anti-racism, was also very important for me. For years, once in the year there was an anti-racist camp, a so-called border camp, at which many actions occurred without permission from the pigs.

Beyond that:

Autonomous plenaries, regularly or on relevant occasions. For a time there was an autonomous plenary once a month / doing presswork, such as the publication ‘radikal’, which was read across the country, although it no longer exists in the autonomous sense, as it was later overtaken more by Marxist Leninist circles and also no longer had its former importance. There was also the ‘Interim’, a city magazine in West Berlin and, later, in all of Berlin, which has been published weekly since the first of May in 1988.

TFSR: What was the significance of the border wall dividing Berlin to the Autonomen and how did that influence radical opposition to the state?

Anonymous: For those of us who lived in West Berlin, the wall was relatively normal, you didn’t push up against it especially and in everyday life it was not so strongly perceptible. Transit across the border was, however, very difficult. You hardly had contacts in the GDR. It was first at the end of the 80s that that changed a little bit. There were always groups that had contacts and also occasionally smuggled something over, which was important for the left in the GDR, but that was very marginal. It was first in the 1988 Anti-IMF / World Bank campaign, at which point there were also activities happening in East Berlin, that contact really occurred. That was also because there was not so much resistance from the radical left that was visible. And this was actually the case – it wasn’t just how we saw it. There just was very little organizing going on.

In West Berlin there was the specific situation that we had a special status. Throughout West Germany you had to do military service but the inhabitants of West Berlin were exempted from this and people who wanted to escape from serving in the German Armed Forces came to West Berlin. There were many students, since there were two big universities, cheap rent, no curfew and wages were 8% higher than subsidies in West Berlin. Because of that there were a ton of people who came here that tended towards being leftist. This was similar to in other university cities but more so because of West Berlin’s special status.

Then, there was also the situation in the houses, that is, in the occupied houses, which functioned as utopias, where a lot was developed. At the start of the 80s there were 144 squatted houses in West Berlin, which also had to do with the fact that it wasn’t the capital city, or anyway, wasn’t yet. Berlin first became the capital city at the start of the 90s after the annexation of the GDR. And because of this it was possible to have small islands within the city where a lot of organizing and alternative life became possible.

Another anecdote on the situation with the wall: In May 1980 the so-called Kubat-Triangle was occupied, a space that, because of its curious boundary line, wasn’t controlled by either the East or West, since it officially belonged to the GDR but existed behind the wall in West Berlin. The tent town that was erected there was called the Kubat-Triangle, named after Norbert Kubat, who was arrested on the morning of May 2nd, 1987. He was accused of disturbing the peace in the context of the first of May. But when his application to be released on bail was rejected, he took his own life in detention on May 26th, 1987. When the West Berlin pigs finally wanted to evict the space anyway, the occupiers scrambled away over the wall and were received by the GDR border guards with coffee and cakes. And in this way they escaped repression.

Another anecdote is that there was a pirate radio broadcast in West Berlin, which was produced in East Berlin and then smuggled over. Because the wall, of course, couldn’t prevent a radio or TV transmission from being received in East Berlin.

TFSR: What comparisons and differences can you find from the autonomist Marxists in Italy who predated the German Autonomen movement? How do they compare to the Anarchists who now use many of their tactics in street battles?

Anonymous: The concept “Autonomous” originated in Italy, in the Autonomia movement and was first applied here in the course of the 80s – the autonomous movement existed in Italy in the 70s, already – there is this real connection, then, of course, but in the everyday lives of people who referred to themselves as ‘autonomous’ in the 80s and 90s, this connection wasn’t really perceptible. There were connections between people, West Berliners who spent a lot of time in Italy, but only among specialists. There was no big, conscious connection and also no synchronicity between struggles. For us that was relatively unimportant, at the start of the 80s in Italy repression became really strong again and it was first then that stuff really started happening here.

Purely factually, there are nevertheless connections and also differences. There were differences, since in Italy the movement was more Marxist oriented and concentrated on the workers’ movement and factory struggles. In the FRG autonomous scene, things were more undogmatic, against organization, subcultural, and the housing struggles and anti-nuclear movement were stronger.

One thing we had in common was street militancy, militant actions and the rejection of established parties and unions.

TFSR: Can you speak about the repression by the CDU (Christian Democratic Union party) in West Germany of the squatters movements in the early 1980’s? How would you describe those occupying houses and what repressions did they face at the hands of the cops? Did this help to build the Autonomist movement?

Anonymous: The repression against the central squatters’ movement – in other words, searches, surveillance, evictions – that existed regardless of what party was in power. In that sense the CDU wasn’t much different than the SPD, the Social Democratic Party. At the regional level there were very different interests. There were also individual deaths. For example Klaus-Jürgen Rattay died when he was driven into traffic by the pigs in the course of an eviction and was run over by a bus. That was only in individual cases, though, we didn’t have to continuously mourn deaths.

Almost half of the houses were evicted within a few years. That was the case both in the squatter’s movement of 80/81, as well as in the 90/91 movement that occurred when much of the eastern part of the city was squatted because of unclear property relations. About half of the houses remained. A part of them are still political, others exist in the pacified form of living projects without public spaces or major political organization.

There was definitely a radicalization that occurred through repression, at least for individuals. But I wouldn’t see that as a general phenomenon, especially as there were also some deterrent effects when people got beaten up – whether in evictions or on other occasions.

TFSR: May Day of 1987 in Kreuzberg, Berlin, is noted internationally as a point in history when people fought against the state ferociously in the streets and set a tone for future May Days in Germany. Can you speak about May Day in Berlin, starting with that particular year? How did the day move from boring Socialist marches to street battles?

Anonymous: Starting with the riot on May 1st, 1987 there have been large independent revolutionary May 1st demonstrations, which usually turn out about 10,000 people. There was only one occasion, in 1994, when there was no demonstration, since in the previous year there was a conflict with a small Maoist Stalinist group, which we had to fight against at the demonstration. Then we just abandoned it the next year. Otherwise, every year there have been demonstrations and the participation also hasn’t fallen off majorly in the course of 25 years. At the beginning the participation might have even been a little bit smaller, but now the number is consistently around 10,000, I’d say.

A great self-consciousness occurred from the 1987 riot that we could also do something ourselves on May 1st, and not just always be small blocks at the official DGB demo organized by the federation of trade unions. Since the danger of cooptation by parties and unions was constantly being bemoaned this was also a good alternative. Just as an explanation: the unions in Germany are more the social partners of capital, in other words very bourgeois, established and hierarchically organized. An exception to that is the FAU, the Free Workers Union, which is organized anarcho-syndicalistically but which is very small although it’s been active since the 80s. There are always still small radical blocks at the big union demonstrations on May 1st but this revolutionary, or so-called revolutionary first of May demonstration is more relevant.

Since, for about ten years, the Nazis have also had demonstrations on the first of May, our demonstration doesn’t take place in the day but rather more towards the evening, when we’re finished with the anti-nazi activities and blockades. These also partly take place outside of Berlin, for example in Leipzig, which we travel to. My own assessment is that as an effect of the later time and also a decrease in the organization of people who go to a demonstration or who specially go to the first of May demo, as well as through a continuous increase in the use of cell phones and filming, that rioting has definitely become much more difficult as a result of that – that is, the attempt to give the pigs an answer to how he are harassed in our everyday lives or have to experience more state violence at smaller demonstrations. The conditions for that have also become continuously more difficult. That is also our fault, there are less and less solidly organized Autonomist groups of the sort that might have built and defended barricades on other occasions and would have agreed beforehand how to act and not have just started drunkenly throwing shit. That has changed. The arrests of drunken and overly curious individuals has definitely increased. That would be my own assessment.

In my opinion, the demonstration still has content, every year there is a new consideration of what should be taken as the motto, what is currently important. It is more and more organized by people, though, who have been active with the Anti-Fa, and less so by Autonomist groups. We have also pulled ourselves back from that. Partially, that’s because we’ve become weaker and the Anti-Fa has taken over more and partially because we were also annoyed by this approach that was always trying to be “bigger, higher, faster”: that is, huge trucks costing many ten thousands of euros when last year maybe we had an unpermitted demo, since we thought we could also manage that. The Anti-Fa groups are strictly against that, though.

Since the opening of the wall, the demonstration also goes through East Berlin or happens partly in the West and partly in the East. For example now on the first of May a few days ago we went to the city-center, Mitte, part of former East Berlin, although that is perhaps not so relevant anymore, rather that it is the current center of power. This year we managed, with 10,000 people, to make it there. Last year that was prevented by the forces of repression. That was definitely a really good success. At the beginning, when the first of May demonstration also wanted to go through East Berlin after the fall of the wall, there were critiques on the side of radical leftists in East Berlin and the GDR as a whole that since there had previously been state organized first of May workers’ demonstrations in East Berlin and the GDR and that was seen as a sort of thorny issue, since the people who lived there had no more interest in the GDR and would not initially find that so great. For that reason, at the beginning there were a lot of questions about what route to take.

But when dogmatic groups took part in the demonstration with Stalin and Mao flags, we as Autonomists felt that was really too much. The demonstration was also organized by radical leftist groups, not just by Autonomists, although we played a major role in it. The Stalinist Maoist ML-Groups had their own small demonstrations 10 years ago but they almost don’t occur anymore.

The second of May was always also the day of unemployment, since we naturally had no desire to work. That was then expressed by us having another action or demonstration on May 2nd. That hasn’t had such a big resonance for a while, though.

TFSR: What were the general goals of the first Black Blocs? Were they ancillary to street protests, for instance as protection or break-aways, or did they exist as protests on their own?

Anonymous: The concept or phenomenon of the “Black Bloc” wasn’t a self-chosen concept but was, rather, used by the media when they were denouncing us and applied there as a label. Appearing militantly at demonstrations in blocks or chains was something that already existed in the 70s at anti-nuclear demos, when there were still no Autonomists labeled as such but rather communist groups that were also actionist and militant- there were some of those, not just groups sitting around bullshitting. The earmarks that you could already see then in the late 70s and early 80s were: black leather jackets, helmets, cudgels, masks, protection on the arms and shins, only walking with people in chain that you know – that helped bring about a feeling of identity and strength and to deter the pigs from singling out people, so it also clearly had a functionality and it was also an expression of the critiques that one raised against boring and unimaginative marches that you shouldn’t just appeal to the state but express a militant position. The concept ‘Black Bloc’ was first slowly adopted by us in the 90s. As it sometimes is that you eventually take up these kinds of concepts. By then it looked a little bit less diverse, though. Previously, in the 70s and 80s it was still a little bit more colorful. The group “Antifa M” from Göttingen, for example, played a role in that, and tried to get people to take on a sort of uniform with their unified appearances and their strong militant fetishism. But of course it is also the case that there is a pressure from lots of filming, since the pigs are constantly filming. People who are standing at the edges are also constantly filming. When an action really takes place on occasion, for example a conflict with the pigs, then it’s extremely dangerous to be so clearly identifiable. So for that reason this black, that is, the really black black, very unified, that is definitely a difference from the 80s. It was a lot more colorful then but it also wasn’t so dangerous.

The goal of the black block organization is, on the one hand, a feeling of strength, but also deterring the nazis and pigs, breaking through police barriers, self-protection against singling out individuals, and creating actions during a demo, such as spray-painting or attacking fences and buildings.

TFSR: Accusations have been made that those participating in radical street protest in the United States are privileged males. What sort of people did one find behind the masks of May Day 1987, for instance?

Anonymous: There were discussions here, too, of course, inside the autonomous scene about macho dominance, about the masculine connotations of militancy that were started by women, by feminists. There’s still a lot of discussion about that, when something happens, but also just in principle. This led, as far as I have heard, to feminists making their own blocks at demos in the 80s, sometimes at the front, so that we managed to be the first block in the front of radical leftist demonstrations or had our own demonstrations, some of which were militant, sometimes with property destruction or actions by women only or later lesbians that led to squatting. Squats that were run only by women.

At this point I should probably say though that masculine and feminine gender roles are of course very deep inside of us, we don’t want to deny that at all. But a collective strength develops through group discussion, through a group feeling, so that in the context of organized militancy, in our public appearances, these gender roles, which are decisive in relation to militancy, since women don’t learn to go into the first row and throw stones and defend themselves against police brutality, through mixed but also gender separated discussions, it was always definitely possible to break through that: on the one hand to find new forms of action, on the other to take part in existing ones without following the social conventions we’re given, that men take over the job of being strong and throwing things – sometimes we could really get entirely beyond that. This is a discussion which is hardly new these days, but as far as realizing these ideas in our own forms of action and organization, I would say things have really declined. In my perception, that was a lot stronger in the 80s.

But just to say in general once more: we’re a mirror of the movement, we come from the middle class, are young, with more men organizing in our groups. That was even stronger in the 80s than today, but that’s no surprise.

As far as the first of May 1987 goes, when the cops in Kreuzberg couldn’t get into certain neighborhoods anymore, other groups took part in that as well, some individuals took part in street fights, in looting and confrontations with the police. We really broke through the limitation of militancy to Autonomists. A lot of people found their courage and participated, completely normal people, that had never done anything like that and probably never did again.

What’s kind of implied in the question, with the concept of privilege, I think, is that the population of poor people here in Germany isn’t a large enough mass, that you would have to say that they are staying quiet and it’s just us, who are acting as their representatives. I wouldn’t say that. Certainly, we are privileged from our backgrounds: most people doing radical organizing tend to come from the middle class but there’s not a large, impoverished population doing nothing.

TFSR: In your recollection was there a large Feminist movement during the Autonomous movement in Germany? What sort of activities did the Feminist movement participate in and was Feminism a trend within Autonomen or alongside it?

Anonymous: The feminist movement was definitely stronger in the 80s that it is today. Also stronger than it was in the 90s. In terms of the Autonomists, from 1987 there was a break between mixed groups and women and lesbian groups. That was during the preparations for the IMF/World Bank meetings here in West Berlin. We prepared for a long time, almost two years. And during that process there was a strong movement to organize separately, because a lot of people, relatively speaking at least, were just sick of the machismo in the discussions – I’m sure you’re familiar with that as well. The result was an independent organization during the IMF/World Bank meeting. There were separate actions by women and lesbians, but always in arrangement with the larger organization. There were also groups that developed out of that which existed for many years later. The women’s organizations from 68 were definitely the precursors. And there was still infrastructure, which could be used. And of course also consciousness, in any case, and women, who came from the offshoots of these attempts of the 60s, women’s groups, bookstores, or separate meeting places or days in mixed places. That has all continued over the years, but it has weakened a lot over the last 15 years. As autonomists we were definitely mixed until this break and after that, not all women organized separately, I didn’t, but it did shake things up pretty strongly.

One point of orientation was the Red Zoras, an urban guerrilla group of women, as a separate organization of the Revolutionary Cells, which were mixed. There were militant women’s actions about all possible themes, not just so-called classic women’s themes. But there was also an orientation on those issues, in the content and practically, for example in militant nighttime actions by women’s groups, which have definitely receded in the course of recent years, or even longer.

It’s worth remembering the Walpurgnis Night demonstrations, on the evening before the first of May. Since the 70s there were women’s demonstrations, which were quite large, with several thousand people. But they got smaller and smaller, until they didn’t exist at all. There are still very small actions, but Walpurgis Night hasn’t been just about women for a long time.

TFSR: At the time, Germany was a destination for huge numbers of Turkish immigrants. Can you talk about the problems they faced and what relationship the immigrants had with the Autonomous and squatter’s movements?

Anonymous: In Kreuzberg there are lot of immigrants, also from Turkey. As far as autonomous squats go, there was very little contact from the side of the immigrants. At the beginning of the 80s, there were maybe two or three projects run by immigrants, for example I know there was a women’s group with a squat for immigrants in 1980. But there was little overlap, little contact in general in the whole organization.

Mostly in the Antifa, which was already important in the 80s and not just after the fall of the wall. Fascists, who sometimes came to Kreuzberg and attacked people, but also state racism. But mostly it was because of organized fascists, that the autonomists got together with other groups, with youth groups like Antifa Genclik, a Turkish antifascist youth group. That was very productive and went on for a few years, but it wasn’t very fundamental for the autonomist movement, it was more of a peripheral thing.

One thing that has to be said here is that many people who came here, or whose parents came here, if they were leftists, often came from Marxist-Leninist groups or Marxist-Leninist influenced groups in their countries of origin, since there were often very few undogmatic or anarchist influenced organizations there. Another reason for the separation could be that the rejection of the bourgeois way of living and of the family, in which the 68 movement had at least started to take some steps, was much stronger here than in immigrant families. And the male dominance in Marxist-Leninist groups is nothing new. In the German movement it was like that in all the communist groups as well.

And on our side, you could say that there was not much openness with people that didn’t correspond to the scene codes, with so called conformists or normals, which comes from a kind of group identity. If you reject the prevalent bourgeois life, then it’s difficult to be open with people again, who obviously or seemingly go along with it. That concerns other parts of society though, people that live more in conformity or „aren’t like us“ It’s harder to make contact, because our idea of another life is not limited to just wanting another government or to organize ourselves differently, but rather includes everyday life and our own development and our own reflection, and so it is just harder to come together so completely with single issue movements or activities, like Antifa.

In the last few years, in my opinion, that has changed a bit, that people with an anarchist orientation from southern and southeastern European countries are coming here more and so friendships are formed, although always with the condition that they belong to the same subculture. It’s almost a requirement, since most friendships get started through subcultural events and things like that. Maybe it’s a shame, but it’s like that.

TFSR: Is it correct to use the past tense when speaking of Autonomen? Does the tendency still live and breathe?

Anonymous: I wouldn’t speak of the autonomists in the past tense. We are definitely fewer than we used to be, just as in general organizing in the radical left, whatever it’s called, autonomist groups or communists or anarchists, from my perspective since the beginning of the 80s has lessened. And the level of organization, the self-description is also quite different. Organizing together and accomplishing something, implementing it, doing collective activities, that’s all declined. So it’s no surprise that we, as Autonomists, also have decreased.

But I’ll add that we are still continuing, we’re still active in small campaigns, and can’t do otherwise, because so little has changed. There are still opportunities to get together and try to organize collectively with non-autonomists. And the self-identification as autonomist, as autonomist groups still exists, although it has decreased.

TFSR: Can you talk about other tactics and strategies employed by the Autonomen that have influenced movements in, for instance, the United States among Anarchists? I’m thinking here the refusal to dialogue with power, the refusal to separate the means and the ends, and a struggle against representation and representatives?

Anonymous: I can imagine that some things have crossed over, it’s definitely so in the other direction. 99 in Seattle was definitely a point of orientation for us here, or an impetus for militant summit actions, which we took part in here. Summit actions in the sense of organizing summit protests and traveling to various other European countries and participating in more or less militant actions with other European groups. Seattle was an inspiration. We always thought in the US, there’s not much going on, not much organization, not really any militancy in the streets. And in Seattle, it might have been more the bad tactics of the police that were responsible for that. But it generated a lot of excitement, I want to emphasize that. Especially since there wasn’t so much going on here at the time. In the middle of the 90s. The atmosphere was under the influence of the fall of the wall and emerging or intensified nationalism, racist attacks, Nazis on the street and so on.

TFSR: The use of masking up as a street tactic has prompted the passage of laws around the world against masks. In Quebec during street protests, for instance, against austerity last year. Can you talk about how this happened in Germany and what the response among the Autonomen movement was? How did the population view the use of masks during manifestations?

Anonymous: To the question of masking up and in general of legalism, I would say „whoever doesn’t defend themselves, isn’t living right“ That’s an expression from the 80s. And when you do defend yourself, you get a reaction from the state, from the state monopoly on violence. This is clear. To me the question sounds a bit like „can’t it possibly scare off people from participating in campaigns like the one ones you do or support?“ And I think that’s difficult, because we’re doing that for a lot of reasons. The orientation on the general ‘normal population’ isn’t actually decisive for now and shouldn’t keep us from using such tactics, in my opinion. We don’t want to end up being assimilated, in order not to be conspicuous or to look bad. For us that was more of a Marxist-Leninist idea from the communist groups of the 70s, and look where they ended up.

To the state ban on masking up that was introduced under Helmut Kohl’s government in 1985, I would say that, because of it, it became more difficult to mask up, of course. It was tried again and again, as on the first of May last year. It’s tolerated to some degree, because it’s not seen as being particularly important at the moment, or because the leadership has other priorities, but people still get pulled out, of course, when the cops don’t want it. Other alternatives have been considered, dressing up very colorfully, with sunglasses or scarves or fake noses. But then there’s always the question of whether that is really achieving the same goal.

There were the pink and silver actions, for example, where people dressed cheerleader-style in silver and pink and were no less masked up for it than if they were all in black, but that didn’t work very long, because the cops caught on quickly that this was also a militant block, that will go through barriers or police controls and does actions during the demonstration and then it wasn’t so functional anymore. But those were considerations, which came out of the context of the mask ban and how a block can still accomplish its goals.

. … . ..

Free Social Radio 1431 Updates

Free Social Radio 1431AM: Greetings from Free Social Radio 1431am in Thessaloniki. After the evacuation of the squat in Biology School of Health on 31st of December 2021, while the ground floor where the squat was located remained demolished for more than four months, with bare cables hanging and the general situation being unsustainable, directorial authorities decided to start the restoration procedures of the new library on the first day of Easter holidays. Riot police, security guards, and various other kinds of rubbish guarded the building and guarding the ground floor debris. Obviously, this did not go unanswered with students and people in solidarity being gathered within minutes. The cops when they saw the crowd gain momentum attacked them with tear gas shot between the crowd and beatings. Eventually, the students pushed the cops back, which did not stop them from showing up on the following days where the reaction was the same.

After the end of these operations, we faced the ground floor as a completely sterile academic space. The response given to this renovation was clear, stating that this squat would not be easily written off. After this, on the ninth of May, the university authority ordered its uniformed garbage to once again guard the workers of the crew, blaming the people who oppose the evacuation of the squatted Biology School for the chaos that has been caused on the ground floor and in the university in general, calling them to take responsibility for their actions, and announcing that because of this, some faculties will remain closed.

Finally, once again this attack was collectively responded to with an immediate gathering of people outside of the squat in Biology School, and then intervention at the rectory of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. The cops fired firecrackers and flash-bangs, this time in the inner enclosed area of the Faculty of Science in the University of Thessaloniki, and caused at least three injuries of students, with one of them having a ruptured eardrum and two arrests. One of which was made in a very violent way.

The student associations are calling for general assembly’s, marches, and have even decided to occupy schools with the main demand to remove the cops from the university campus. It should be noted that the bill for a permanent presence of University Police has been voted through by the Parliament, and they want it to be implemented on 17th of May, 2022 The day before the elections of the student unions.

. … . ..

Germinal Social Center in Trieste

Çrna luknja: Yes, we are very happy in Çrna luknja to again have the opportunity to call to Trieste. We hear that you are in festive mood these days, we will come to this shortly. First, please, can you tell us just a brief history of the anarchist group Germinal. When it was established, where was it active in the past, about the new place, etc, etc?

Germinal: Yes, our group is an old group, a very old group. It is about 70 years old and began to make action and to make anarchist politics from the beginning of 1900. And so go on for many days. We had our own space in the center of the city of Trieste, and the forces of state order kicked us out.

Çrna luknja: Maybe can you explain a bit more? How did you reach a decision to get a new place? I mean, how did the whole process go? Were you able to do it on your own? Or how was it?

Germinal: We made a call to all of the anarchist movement in Italy and also in Europe to collect the money to buy a new space. Part of the money we collected with this call, as well as from a grant from Magaze who lend some money to social projects, or not commercial projects but solidarity projects.

Çrna luknja: So what impact did it have on your political work to have this new stability, having own social center in a city like Trieste? I imagine it makes a very big difference to have the stability to be able to plan for the future

Germinal: Now with a new place, we decided to take space in the street. So, its more open to public or to the people. Then we open it to a lot of associations, now we are more open than before. So for me it’s very good, a way of making anarchism in practice. We are in social struggles in the city, in all the social struggles. Also in Italy, we are in the anarchist federation.

Çrna luknja: So we can expect that also, your celebration will be very interesting. The celebration of 10 years of your new social space. So I think we want to visit. Can you tell us something about the program we can expect for the anniversary?

Germinal: Yes, sure. This year we have two days of celebration, on Friday the 13th and Saturday the 14th. On Friday, we will do a presentation of our library, social library named Umberto Tomassini after an older comrade of a group Germinal. And on Saturday, we will make a demo around the city zone and an after-party in our social center, and all you are invited!

Çrna luknja: Thank you for this little historical briefing and thanks for the update on how the new space is affecting the anarchist politics in the region.

Germinal: Okay, thank you. See you next week. Ciao, ciao.