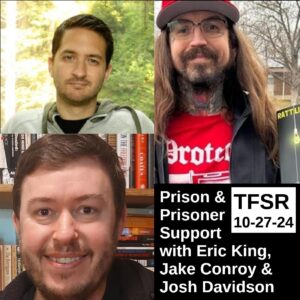

Prisons and Prisoner Solidarity with Eric King, Jake Conroy and Josh Davidson

This week we’re sharing a discussion recorded some months back in the pacific northwest featuring former political prisoners Eric King, who went in for actions in solidarity with the Ferguson Uprising in 2014, and Jake Conroy, who was convicted for coordinating successful anti-vivisection divestment campaigns against Huntington Life Sciences as one of the SHAC7. They are joined by Eric’s co-author of Rattling The Cages, Josh Davidson. We hope you appreciate the wisdom and passion of the discussion.

You can find Jake’s youtube channel The Cranky Vegan for a long-running and ongoing commentary on animal liberation topics. And you can follow Eric’s panels with other former prisoners and supporters on the instagram for Rattling The Cages and past media and articles by and about Eric (including past interviews we’ve done with or about him) at SupportEricKing.org and find more from Josh at linktr.ee/JoshDavidson..

Prior interviews:

- With/about Eric

- With Josh

- Jake Conroy at ACAB2024: audio

- Jake’s former co-defendant, Josh Harper on the movie about their case, ” Animal People”

There are two upcoming Firestorm Books political prisoner panel talks in November, both of which you won’t want to miss.

- Saturday, Nov. 9th, 7:00pm – 8:30pm ET, Eric King will be talking with Jason and Jeremy Hammond. Register now!

- Saturday, Nov. 23, 7:00pm – 8:30pm ET, Eric will be talking with Linda Evans, Laura Whitehorn, and Nicole Kissane. Register now!

A few other things (per Josh):

- BPP/BLA comrade and former NY Panther 21 defendant Dhoruba bin Wahad needs our support. Help if you can!

- The 2025 Certain Days: Freedom for Political Prisoners calendar is now available, and it’s beautiful. Get one or 100 today!

- If you missed the last panel talk with Eric, Jake Conroy, and Claude Marks – or any of the previous 6 Firestorm Books panel talks – watch them here.

- Don’t stop talking about Gaza, genocide, and US imperialism. Long live all those dying every day for Palestine.

. … . ..

Featured Track:

- Walking Is Still Honest by Against Me! from Crimes As Forgiven By…

. … . ..

Transcription

Host: Alright, everyone, we’re going to get started. Thank you for coming to this event on a Tuesday evening. The weather is nice outside. You could be out there. But I want to welcome you all and give my gratitude to our hosts, Eric, Jake, and Josh. I’ll give them a chance to introduce themselves. First, we will do a little bit of what I think people in the theater business call housekeeping. So first of all, this event is a fundraiser for the July 25th International Day of Solidarity with Antifascist Prisoners. That day of solidarity has been going on for many years now, and while the day’s on July 25th,, we couldn’t get this event to happen on the same day, so we pushed it back a week. No big deal. There is a money jar on the back table. You can put cash donations in, as well as the written down Venmo account where you can send electronic donations. That Venmo is IADF206. The International Antifascist Defense Fund will receive that money and then dole it out to tens of antifascist prisoners internationally who are locked up for various antifascist crimes. At this event, we will talk about prisons, prisoners, and political prisoners, and use that as also a way to get some financial support going for people who are currently locked up for the struggle. Before we get much further, though, I want to invite somebody from a support campaign for a local anarchist prisoner named Amber Kim to come up and give us a little update about what’s going on with Amber.

Morgan: Alright, hi, my name is Morgan. I’m here to talk about my friend Amber, who is a trans woman in Washington State Prison. About a month ago, Amber was beaten by guards and forcibly transferred from a women’s facility where she had been for the last four years to a men’s facility. The reason that the DOC gave for this was that she was having consensual gay sex with other people in prison. Most people are probably familiar that gay sex happens in prison all of the time, and Amber now faces a serious risk of harassment and further violence in a man’s prison as she is trans. The other person who she was accused of this violation with did not get transferred to a different facility. She’s very clearly being discriminated against because of being a trans woman. This is to our knowledge the first time that the DOC has transferred a trans woman out of a woman’s facility as a result of an infraction. This creates a really dangerous precedent for trans women in Washington state prisons. I wanted to share a quote from Amber. This is from an article that was written in Truthout by Victoria Law weeks ago. Amber said, “The most important thing to consider is that I’m not an outlier. I’ve been able to gain attention to what is normal. The use of state-sanctioned violence to force people into unsafe situations is normal for the DOC. The disregard of a person’s understanding of their safety is normal for the DOC. Discrimination against LGBTQ people is normal for the DOC. I’m not special. I happen to have some luck bringing attention to this issue.”

So over the past few weeks, Amber has been in solitary confinement in a men’s prison. She concluded a 17-day long hunger strike, and on the outside, a lot of people have been doing weekly call-in campaigns to support her, as well as sending letters to her, as well as letters to the DOC. We are really trying to organize around this one because Amber is really close to a lot of us on the outside. I’ve been friends with her for six years. A lot of other people have been friends with her for many, many years, and she has shown up super hard for other trans women in prison. That’s one reason why we’re pushing hard for her, but also because this is really a litmus test for how much violence they can do against trans women in prison and to see that they can do this to other women in the future. So we’re really trying hard for people to show up now to let them know that they try to do this to other trans women, that people will make a huge noise about it. We’re asking you today to do two things to help us. The first is if you have Instagram, you can follow our support page on Instagram. You can take out your phone and it’s @Support4AmberKim, and there are some flyers back there that also have that information on it. The other thing is that there are some postcards in the back that folks are passing around right now that will go to Cheryl Strange, who is the first openly gay secretary of the DOC, and she, during Pride Week, sent Amber to a men’s facility. Obviously, we know that gay people in places of power don’t do anything for us, so we are trying to let Cheryl know that people are paying attention to this situation so that we can hopefully put pressure on them to send her back to the women’s facility. You can drop those cards off at the table back there, and we will put a stamp on them and send them out. That’s it. Thank you all so much.

Host: Before we get any further, I also want to give a quick update on some local prisoner cases here. People who were locked up elsewhere in the country before the uprising that happened in 2020 after the police murdered George Floyd. The first person I want to talk about is Tyre Means. He was arrested, charged, and sentenced to several years in prison for helping to burn down a police car during the uprising on the first day of the riots and then stealing a police officer’s firearm off the back. I’ve been a pen pal with Tyre for years since he got locked up, and through our friendship, I’ve come to find that Tyre’s like a really sweet individual who also fully believes in a generalized popular revolt against the violent white supremacist police state. He’s a really sweet kid. He’s currently locked up in Victorville in California, after suffering some pretty intense physical harassment when locked up in Texas at a prison locally known as Bloody Beaumont. So I encourage you all to keep Tyre’s name in your memories. And I’ll give you an idea of how to get access to his address. You can write him later. He’s at USP Victorville. And then I also want to highlight Marge Shannon, who was locked up after social media photos identified her as being responsible for also setting a cop car on fire in 2020. Marge has been really steadfast in her time and has been bounced around a couple of different prisons. I want to highlight these two folks who were arrested for their activities over four years ago, those people are still in prison. And many people are still in prison for what they did during the George Floyd uprising in 2020. So I want to encourage you all to keep those names, Tyre Means and Marge Shannon, in your memories and head to uprisingsupport.org to find their addresses so you can write the mail and the addresses of many, many more individuals who are still locked up.

All right, now that we’re done with all the housekeeping, let’s welcome our lovely guests. We’ve got Jake Conroy, who is a contributor to the book Rattling the Cages, and then we’ve got Josh Davidson and Eric King, both editors for this lovely, massive volume that everybody should read. And Eric King is also a contributor. So let’s give them a round of applause. Do you guys want to do quick brief intros? Yeah, let’s start with Jake.

Jake: All right. How brief?

Host: 15 minutes? I’ll yell at you.

Jake: What would you like to know?

Eric: Name, crime… [laughter]

Jake: Perfect. My name is Jake Conroy. I live here in the Seattle area. I was sentenced to 48 months. I served 37 months in two prisons, one in Victorville, a medium-security prison. That’s a prison industrial complex, so there are four prisons in total: two mediums, a penitentiary, and a women’s camp. And then I was transferred to Terminal Island, which is a low-security prison, which is an island literally in the harbor of San Pedro, Los Angeles. I do an hour-long talk about my case and the time I was in prison. I’ll try to condense it to about two minutes.

Basically, myself and some friends ran a pressure campaign against an animal testing laboratory. So on the face, the campaign was very rooted in animal rights, but the core of it was really a fight against capitalism because we weren’t protesting against this giant laboratory. We were protesting against anyone and everyone that was associated with it. So we protested against the world’s largest banks, the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, the world’s largest insurance companies, the auditors, you name it, anyone associated with it, shareholders, stock brokers. We were at protests against the New York Stock Exchange. We were able to essentially get over 100 of the largest corporations in the world to do what we wanted, which was to stop funding and supporting this laboratory. We got them kicked off the New York Stock Exchange. We took their $30 share and made it worth about two or three pennies, and we crippled this corporation. And by we, I don’t necessarily mean me and my friends that did this organization called SHAC, but this global, grassroots, non-hierarchical movement that could participate in any way that they wanted.

When you have that much of an effect on capitalism, the government takes notice, as does the corporation, of course. We were sued 23 different times. We had a federal civil RICO suit brought against us for $12 million apiece, and eventually, they arrested six of us and charged us with a variety of charges. The main one was called the Animal Enterprise Protection Act, which is now called the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act, which is a law that was specifically written for animal rights activists who are driving around the country and raiding laboratories and fur farms and releasing animals and smashing them up. And the law says, if you cross state lines and disrupt a business that uses animals and you do more than $10,000 for the physical damage to the property, they can try you as a domestic terrorist. In our case, they said we crossed state lines using the internet because we were organizing online. The online organizing space was new. This was from 2001 to 2006 but nonetheless, we did more than $10,000 for the economic sabotage, or economic damage, to this corporation, and therefore we were all found guilty under this charge and a variety of others. I was sentenced to, as I said, 48 months, basically, as a domestic terrorist in federal prison. And that’s how I did my time.

Eric: My name is Eric. This is my first time speaking outside of Colorado since being released, so I’m very excited. I appreciate all of you coming. I was released seven months ago after doing about 10 years for firebombing a congressman’s office in solidarity with the Ferguson uprising after the police killed Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. My community was not stepping up to the plate in Kansas City. So after going down to Ferguson for a few days and seeing what those people were suffering through and the risk that they were taking to defend their communities, I thought it was my obligation to join them in that struggle. So I did what I had to do. I ended up doing nine years and six months or some sh*t like that. I was released seven months ago from the Federal Supermax ADX, where El Chapo is at, where all those motherf*ckers are at. I did it for about two years there. I’m one of only a handful of people to ever be at every custody level. I started at low, and then medium, then penitentiary, and then finally supermax for resistance inside prison. I’m so happy you all are here. Thank you.

Josh: And my name is Josh. I’ve never been to prison, but for the last dozen or so years, I’ve spent most of my time supporting people who are in prison or have been in prison. I’m a member of the Certain Days: Freedom for Political Prisoners Calendar collective, which has been around for 25 years now raising money and raising awareness for political prisoners. And I edited this book, Rattling the Cages, along with Eric. It was his idea when he was at the ADX, and I interviewed about 40 political prisoners with questions that we came up with together. It was our hope that the book would not only help raise funds and awareness for political prisoners, but also help share their stories and help get more people involved in supporting them.

Eric: Greatest thing I ever did!

Host: Well, thank you for those introductions. To get this started off. I wanted to highlight one of the chapters in Rattling the Cages provided by Bill Dunne, an anarchist political prisoner whose prison sentence actually started here in Seattle, Washington when he attempted to break out a comrade from jail at the King County Correctional Facility in downtown Seattle in 1979. During the attempt to jailbreak, there was a driving shootout between Seattle police and the car carrying Bill and two of his comrades. Bill’s attempted to break out of prison at least once since then, and had his parole rejected in 2014 due to his political beliefs and his refusal to disavow anarchism. Bill is currently in a medical facility to receive cancer treatment. His chapter in the book stands out to me, not only because he wrote it from behind prison walls, but as a long-term prisoner who’s carried on the struggle in a principled manner for over 40 years. He almost normalizes the state of conditions in prison while detailing his time there, which I think can be important for reminding readers who’ve never been in prison that the struggle does not stop when one is put in jail, but rather it continues. For the three of you involved in this book, how did the words of Bill and other elders present in the book sit with you? For the editors, what was the importance to you in including words from Bill Dunne and other elders?

Eric: I’ll try to not be long-winded. So I’ve admired Bill and our elders for a long time before I was locked up. Those are the people that motivated me to push this struggle forward in the way that I felt was most appropriate, the direct action way. And I got to meet some of the elders, and I got to hear their stories inside about their resistance, about their refusal to kowtow to these cops. About how we didn’t stop being involved in the struggle, we carried on a different front, and we’re often by ourselves in that. More often than not, you do not have other anarchists, other anti-racists, or other antifascists with you. So it puts your ethics and your commitment to this struggle on the line. It really shows, what are you about? And those dudes really, really dragged me forward. And I use dudes in a non-gendered way. If it makes anyone offended, I apologize. And please, please call me out. But when you see these people that have been down for 20 or 30 years, and they were locked up when these penitentiaries were rocking, they were locked up when it was brutal. It still is, but there are levels. And to see them not only not back down, but grow in their ethics, grow in their spirit, grow in their solidarity and commitment to this movement. When you watch that and read about it, when you pick up someone’s book—like I’m on Dan Berger’s book or something—and you read these stories, it fires you up, and it shows you that this is worth it. And I can be afraid, but I can still keep going, and it’s no different than on the streets, but inside, you really have to find it. You really have to want it. And the old cats really helped me with that.

Jake: I want to say thanks for having me. I want to give another round of applause to Eric. I think it’s remarkable that you’re here. It really lifts my spirit. I’m excited. Round of applause. I’m excited to see you here. It’s a hard thing to do. We all have different experiences of when we’re in prison. Everyone’s got their own story, and none of them are easy. Some may be harder than others, but at the end of the day, no one really knows what it means for that individual and what they went through behind bars while incarcerated. I don’t know all of your stories. I don’t know all of your experiences. I can only imagine and probably not even come close to what they were. So the fact that you’re here and you’re speaking up to the things that you care about and feel passionate about really warms the heart. And I appreciate you. So thank you.

I started doing activism in the mid-90s here in Seattle, and one of the things that I did as a young activist was I devoured as much information as I possibly could about a wide range of different movements. I did a lot of my activism focused on animal issues. But that’s not entirely where my focus was. I really tried to spread it out as much as I could, but it was the stories from elders or people who have come before me or are still around but had done the work before that were really where I found my my biggest inspirations. People who recognized the need for struggle, the need for resistance, and the need to take risks, and they did that, and they did it in really big ways. I looked towards things like the Panthers and American Indian Movement and the Young Lords, anyone and everyone I could get my hands, in books, I read and read. Those groups weren’t perfect. They all had problems. They all had issues. They had big red flags, but there were people in them who did some really amazing and important work, and some of them are still paying the price for it now. They’re still incarcerated, and I know this goes back to the whole point of this conversation—the desire and the need to support people who are incarcerated. But the thing that I really took away from all these stories and things that I read and speeches that I heard and the more I learned about elders and people in the movement that have been around for a long time is the issue around solidarity.

And of course, that looks different to everyone and feels different to everyone, but the thing that always sticks out to me is… Aren’t you guys familiar with Marilyn Buck? If not, you should be. She was one who helped Assata Shakur be liberated from prison, and she passed away. I went to her memorial in Oakland. We were in this church, if I remember correctly, and I was in the last row of the top tier, and in front of me was a sea of people who were incredible people that I read about, learned about, met over the decades, and was so impressed by. And the last person to come up and speak had a tape recorder, and they had a tape-recorded message. They said this tape-recorded message flew from Cuba to Oakland. It still makes me want to tear up, but it was a recorded message from Assata Shakur from Cuba basically thanking Marilyn Buck for essentially trading places with her. And that level of solidarity and respect for a movement, for a cause, for belief, so much so that it might not have affected Marilyn personally as a white person, but they were willing to swap places essentially so that Assata Shakur could be free. And that level of solidarity was something that I really took inspiration from, from people that were back then and even decades later sitting in that memorial for Marilyn Buck. It was such a stark reminder of how much we need to support one another. We need to show up for one another. We need to take big risks and take action for one another, even if we’re not necessarily in the immediate community together. We’re all fighting for liberation, and we all need to help each other out in those fights for liberation. And that’s something that I really took away from, not just that experience, but from all the people who inspired me as an activist and continue to inspire me.

Josh: I don’t have anything to add.

Host: This is a little bit of a generic question, but the three of you all have different roles in this book, so you’re going to hopefully have different answers. What did y’all learn from this book? Josh, you were the editor on the outside. You have to really read and parse through every chapter before it makes it to a published form. Eric, this was your brain baby, something that, in the ADX, you’re not able to create very much at this time, and so you have this seed of an idea behind many prison doors become this massive, 400-page book by AK Press that left-wing folks can keep on the shelf. Jake, you get to contribute a chapter to it and get to tell some very good stories and necessary stories for people engaging in prisoner solidarity. What did you all learn from the process of this book, either creating it, or reading other people’s contributions? What was that like for each of you?

Josh: I can go first. I interviewed 40 people for this book, 40 former political prisoners or current political prisoners, and they all have different stories. They all come from different parts of the movement, from different generations, but they all have love and solidarity as the cornerstone of their lives, which is part of their struggle and of how they survive in prison. That came through really clearly in every single conversation, not only their commitment to the struggle but also the importance of outside support and how much support means to people inside, how much of a lifeline it is to people inside. But really for me, it was building these relationships. I knew maybe a third of the people already that are in the book, but now that I know these other two-thirds and even other people that aren’t included in the book, it really feels like a whole world has opened up of radical and amazing people that it’s really great to not only be a part of sharing their stories, but to get to know these people.

Jake: Two immediate things I learned from the book is one, that I’m lazy, and two, that I ramble. Because I ended up not writing it. Poor Joshua had to Zoom-call me and interview me because I could not get it together. And then secondly, Josh had to edit my ramblings into a cohesive narrative. So I appreciate you. A couple of the takeaways for me was everyone has their own experience. We all have different experiences, different stories, and we all do different time. We all did different time in prison. Meaning some people went about their time, and maybe they studied, maybe they became more politically active, and maybe others were trying to survive. Everyone had a different strategy and experience within prison, and that was interesting to me. But at the same time, we all fell underneath this big umbrella of being incarcerated and experiencing the prison industrial complex very up close and personally, something that perhaps a lot of us have fought previously, or maybe we all did a lot of prisoner support.

It was something I did a lot. I pushed a lot for political prisoner support, but I had never been on the receiving end of that. Being on the receiving end of that was very eye-opening to me about what that means, and I’m sure will get that into that later. But knowing that I was under this umbrella, in a way, was a bit comforting, knowing not that other people were also having horrible experiences in prison, but we were all going through it together, even if it was generationally. Because we did a talk at the Howard Zinn Book Fair, and there were people from multiple generations, all that was in the book, and sharing experiences, and knowing that I could turn to someone that was 30 or 40 years older than me and be like, “Hey, this is what happened to me. Did this happen to you? How did you get through it? What helped you? What hurt you?” And they could talk back, they could answer those questions, and we could share stories and ideas, and we would understand each other. Knowing that there are people spread out around the United States and around the world that I can be in a community within a very special way was a nice takeaway from the book.

Eric: So Jake touched on a lot of stuff, so I’ll go a different direction. I got really inspired to get this book out after Tom Manning died. I don’t know if any of you know Tom Manning, but he’s one of our elders. He’s one of my heroes. A dedicated anti-racist fighter and warrior. He did brutal time. He was also at ADX. He did five years there, and he was someone I looked up to. When he passed away, I thought, I wonder what his life was like like. I wonder not what his ethics are, but what’s your day-to-day like? Did you have friends? Did you ever cry? Did you ever miss your son? And I was desperate to know this because, between me and you, I’m very soft. I am a very emotional person, and this stuff that was happening imprisoned me at these times was crushing. It was hurting me physically. I got the scars, but it was also destroying me emotionally. And I felt really alone. Because when you read about our elders, what you hear is this bombastic, like “We’re fighters. We never back down. We do this, we do this.” But you never get to hear the vulnerability of like, “I cried because I missed my son’s birthday.” Or “My little girl turned 10, and I didn’t get to hug her.” So I wanted to know, am I alone? Am I a *** because I’m crying all the time? But that was really, really important to me to know that I wasn’t the only one feeling this.

When Josh and I formulated the question—Josh made the lot smarter than I could have—and when I read other people’s answers, I saw other people had a bad time. Other people felt things, other people were sad sometimes, and other people made friends. It’s okay to make friends and find happiness because finding happiness is resistance inside. If you can find joy inside of it, you’re beating these mothersf*ckers. When I got to read about different people’s experiences, not only like, “Yes, I’m sad all the time,” but also, “Yes, I’m happy all the time, and I do it despite these punks trying to bury us.” That made me feel… What’s the opposite of alone? It made me feel encompassed. Like what you said, we’re in this together. We’re a unified front of resistance inside of prison, it’s both our joy and our vulnerability that binds us together, and it made me feel so happy.

Host: Thank you. The next question taps right into that. Prisons operate on their ability to isolate prisoners from the outside world. These levels of isolation vary from holding people in the general population to long-term solitary confinement. In many ways, prisoner solidarity organizing aims to lessen this isolation, if not overcome it through actions like letter-writing programs, noise demonstrations, and general publicity and awareness-raising. Sometimes this organizing could lead to overrunning the prison walls, not just metaphorically, but sometimes we do succeed in transcending the borders of prison through struggle.

Was this something either of you, Jake or Eric, have experienced either in your personal time served in prison or through supporting someone in prison? Josh as well. Have you got the moments when our struggles bring us together through the walls? Was that something you guys have experienced when you were locked up?

Eric: I did nine and a half years. Seven and a half of those were in 24-hour lockdown. I was in SHU. That included five and a half years straight bid. For four of those years, I wasn’t allowed phone calls, mail, or visits. I was completely cut off. The reason I was completely cut off is because people did a noise demo about me outside of a federal prison. I was facing new charges for assaulting a lieutenant. And these people did a noise demo for me. It was beautiful, it made me feel so proud. But in the process, they videotaped, they live-streamed it, and they busted up a cop’s car. This is when Trump was doing his big… [mocking tone] “Antifa! Antifa! Antifa!” I’m the only antifascist in the federal prison system at that time. I openly repped that shit.

Because of that, they took away everything. They said I was the leader of Antifa. [laughs] They took away everything because of an act of solidarity. Those people never asked me if I wanted that demo because they couldn’t. I wasn’t able to talk. I was in the SHU. And I would have said yes. I would have said hallelujah yes. But that reached inside the walls. That got me put in a cell with literally just a mattress for three weeks, no sheets, no blankets, no pillows, no food. I got two meals a day. That was reaching inside in a bad way. Reaching outside in a good way was Josh. He wrote me when I was in the SHU at Leavenworth. And that friendship from actual writing in a way that’s not pandering to me as a political prisoner, but as a human being. Addressing me as a real person, it develops into a friendship, and then it can develop into a beautiful project that supports other prisoners. My wife wrote me. That’s how I met my wife. That’s how I became a dad. That’s how I met these two. The people in my life right now are all people that wrote me. I don’t have a single friend from my free world. Those cowards were like “Oh, we’re busy.”

But the people like *** was a friend that wrote me. These letters and this support are not a game. This isn’t like “I saw a flower today, have a good day, bye!” You can change someone’s life. You can take a situation where someone’s having the worst day of their life every single day, five years, six years, and give them a good day. You can give them the most joy in their life when this cop shows up and says ,”mail day,” and it has their name on it, and they know that someone cares. Someone put effort into showing them love, someone tangibly wrote a letter, annoyingly put in a little envelope, put a stamp on that b*tch, and shipped that out. That takes work, and that shows that you really care. And when I was able to get mail, which wasn’t all the time, it made me feel so whole and so complete and brought the most beautiful people in my life, and that’s the connection that it had for me.

We don’t have to clap out there. Just give me a snap or something.

Jake: I want a full standing ovation. [laughs]

When I think of like resistance in prison, I would see some very specific and small pockets of resistance that were really exciting to me. With lay-ins, basically, strikes. In prison, you are required to work a 40-hour work week, and a lot of those folks are working, at least where I was in UNICOR, which is essentially like factories. At Victorville, they were refurbishing five-ton trucks for the military, sending trucks from the Middle East, where you’d be refurbishing them, and then sending them back to the Middle East. Even more f*cked up was that in the penitentiary, they were taking pickup trucks and refurbishing them for Border Patrol, and they would have undocumented people that were incarcerated there, forcing them to do that labor. Those are the high-paying jobs. They’re making $1 an hour. Pretty nice. So the prison industrial complex runs on manual labor, slave labor. We can look at the 13th Amendment and realize that is what still continues today inside prisons.

And beyond working in UNICOR, all the food is cooked, prepared, and served by inmates. All the clothing we wear is manufactured by inmates. All the desks and furniture that people use, particularly the cops, are manufactured in UNICOR by prison labor. So people look at that and think, “Oh, I can make a little bit of money that I can buy some stuff with commissary.” But on rare occasions, at least at Victorville, maybe more so in other places, people realize the power that they had as workers. And essentially doing sit-ins or lay-ins, where we’re not going to get out of bed today. Six o’clock in the morning, they come and unlock your cell, and you had to get up, and you had to go to chow on, you had a breakfast, and then you had to go to work. And if, say, 1300 people at Victorville decided they weren’t going to refurbish five-ton trucks for the military anymore. Not only was that resistance as inmates, but it suddenly was interrupting not just the prison industrial complex, but you’re interrupting the military. And I don’t think a lot of people fully recognize the power that that had. But some people did. And on occasion, there were lay-ins and strikes. People were not getting out of bed. Well, in our unit, we had 120-something people, 120 inmates, and one cop. Okay, so you do the math, one cop is not gonna be able to get 120 people out of their bunks? So there was this real power when people realized, that if we didn’t go to work, they’re eventually going to have to do what we want them to do, they’re gonna have to do what we say.

And on occasion, I saw that in there. That was uplifting. There were times when inmates were being really being taken advantage of and being treated really poorly in the visiting room by certain correctional officers, cops. And it took us the strength of a lot of inmates coming together from all different backgrounds and races and gangs. So in prison a lot of times, at least the one I was in, I’m sure you have similar experience, everything’s segregated by race, by gang, by where you’re from. Everything is segregated. And by design. And so when those groups and communities start coming together, that doesn’t show power, it also shows a very clear message to the administration and to the Bureau of Prisons that this is something serious. These inmates are recognizing their power. And I saw that a couple times where a bunch of different people from a bunch of different groups and backgrounds and gangs, communities all came together to approach the warden and the assistant warden and be like, “Hey, you got a real problem here. And if something doesn’t get resolved, sh*t’s going to hit the fan.” And they took care of it. Not to their credit, of course, but that was because we all showed up and resisted. On the outside, that might not seem like a big deal, but on the inside, that’s a really big deal, at least in the prison I was in. So seeing things like that was really inspiring. Being a part of those things was really inspiring. As an activist, I’m like, “Let’s go. Let’s take this and roll with it into the next spike,” and then the next day, everyone’s rioting and stabbing each other. And it didn’t quite work out that way, but it could have. So it was heartening to be like, “Oh, I hope that little pieces of that stick with the people involved as a reminder that we do have power.”

On a personal level, the case I was telling you about that I was involved in, was the largest FBI investigation of its time. We had an enormous amount of resources from the FBI and private industries used to target us outside. We had our phones tapped. 555 90-minute cassette tapes worth of our phone calls. We had infiltrators. We’re the first group of people in the United States that the government tried to hack into their computers using malware to try to get into our encryption software. I can go on at length about what they did. Naively, when I left the activist role and went to prison, I thought I would be done as Jake Conroy, and I would start this new life as like 93501011, but what I found out very quickly is that the government was there to continue to harass and try to intimidate me into not being able to maintain that sense of self. The ability to do so is very limited. Letter-writing, visitation, and phone calls, which aren’t considered rights, they’re considered privileges. They made sure that I couldn’t get any visits, and I figured out a way to navigate around that and hoodwink the system, which I did. And a friend of mine came and visited, and the FBI showed up at her door a week later. “How did you get to visit Jake? What did you guys talk about? What were you doing?” I was put in solitary because they said there was a threat of me organizing people outside of prison or the threat of me organizing people inside of prison. I’m very lucky in that my solitary time was nothing in comparison to Eric’s. I was on a high-visibility inmate program, where they thought I was one of the biggest threats to prison, and a wide range of things that the government did to try to shut me down.

But if I can echo what Eric said, those little bits of support that might feel like a little bit, from someone on the outside, as a huge, huge boost to people on the inside. I always call letters a jailbreak. Every letter was a jailbreak. You get that letter. And I was very lucky. I got a letter literally every single day that the prison would give me my mail, which wasn’t all the time. But on the days that I got mail, I got a letter. Sometimes I got five. Sometimes I got 20. Sometimes I was getting 50 letters a day. Which is incredible, which speaks to the level of support that we all on the outside understand those on the inside need. But every one of those letters I would take up to my cell, and I’d set them out, and I would open that one, and I’d read the front, I’d read the back, and that was a jailbreak. It was a prison escape. I looked at the picture of the cat someone sent. That’s cute. I got so many pictures of cats, which I appreciate, of course. And then I put that letter away, and open the next one. That was my next jailbreak. If I was lucky, I get five or 10 jailbreaks a day. And every letter 5-10 minutes, I get to read it. And I would read it so slow and savor them. I’d hear about your vacations, the food you’re eating, the television show you’re watching, the camping trip you went on, and stuff you might have been thinking was so boring. No one’s going to want to read this letter. That was me escaping from prison, and then I would get to as much as I could write everyone back. And that was a prison escape. And the relationships I formed with people, similar to Eric, are so special to me. I got out in 2010, and I’m still friends with people that I wrote in prison. I still have very special relationships with them, and I still go and visit, and they visit me, and those things wouldn’t have happened without prisoner support. And so I don’t say it lightly when I say that those letters and the support that I received, and I’m sure Eric received, saved my life. I don’t mean that metaphorically, or figuratively, it literally saved my life.

Prisoner support doesn’t end at the gate, right? When you get out of prison, it’s not over. Some of the most important support I got as a prisoner came after I got out of prison, when I was in the halfway house. Even when I got out of the halfway house and was on probation, some of the support I got from people again were lifesavers. Someone found me employment. I hadn’t had a job since 1995 or something like that, 1996. And it was 2010. I didn’t know how to interact in the world. For the very short amount of time—I was in prison for just a few years—it felt very much like I was institutionalized. When I got out, I was angry. I was raged. Someone cut me in line at the bus, I need to fight that motherf*cker. You know what I mean? If someone cut me in line at the bank or anything, that person needs to get f*cked. That’s how it is in prison. If you’re disrespected, you need to fight. And they’re walking around in society, and you’re getting disrespected everywhere. And that takes a big toll on you emotionally. Having people that understood that and supported you and helped you and made dinner for me, or drove me to my therapy session, or helped pay for my therapy session, or gave me a couple bucks on the side so I could go to the store and get something that wasn’t same f*cking food that I’ve been eating for three or four years. It was like a piece of heaven.

So support people when they get out of prison because that’s really when the prisoner support starts to drag, but that is also when a little bit can go a really long way. You can really help. Your immediate support people, your family, your parents, your kids, your partners, they also need support. They are going through a traumatic situation. It might not be the same traumatic experience that we’re going through on the inside, but they have had their family member, and their loved ones stripped away from them for years, for decades. And a lot of times they can’t even visit them or talk to them on the phone or write them a letter for years. And that’s scary for someone on the inside, but it’s also scary to the people on the outside that they’ve lost their loved ones. So show up for those people as well and support them in any way that they may need or ask for.

Josh: They both have talked about how your letters could change their lives and offer them something life-saving in this horrible place, but it can also change your life. Had I not bumped into David Gilbert’s book and knocked it over in a little bookstore sat there and read it all day and decided to write him, I wouldn’t be here today. Had I not written to him, I wouldn’t be part of the Certain Days Calendar. Every time I visited David, I would ask him what he needed for support, and what he could use. And he would tell me to write to other people, that other people needed that support, that love, and that solidarity. And that’s what it’s all about. You can build these relationships, not through prison bars, but in spite of them. And you can make something really beautiful grow. If you’re lucky, you’ll get them out of prison, and you’ll be able to support them on the outside. But if not, you can still make something beautiful in spite of those prison walls.

Host: All of your guys’ answers touched on the two other things I wanted to talk about, transitioning out to the outside. What would you like to say about transitioning to the outside?

Eric: As I said, I got out seven months ago. I just got out, and it was five and a half years of no contact to now I’m going to a halfway house, and that shell shock was terrible. Every day it was terrible, and I was able to survive that because I had support on a level that most prisoners don’t. I saw people there and I had to call my friends to get them socks because the halfway house wasn’t giving them socks or shoes. You could have the shoes you came in on, and that’s it. We had to get sleeping bags for people because they were kicking them out of the halfway house homeless. They have anywhere to go. Because I had built these relationships and people were kind enough to me I had things like towels, toothbrushes, toothpaste, good socks, enough socks, a hat, things that make you feel human. I had a partner who taught me how to use this smartphone. I never used a smartphone. I never used an app. I still get confused, but I have these things that I know that if every single prisoner had, we could snatch people away from those gates. Because the prison system is set up to where you are hopeless, you have to commit crimes against capitalism to survive, every single infraction can get you put back inside. My case manager in the halfway house tried to get me fired. I got a career when I got out. People who wrote me, we became close with, became my lawyers, and then hired me at their law firm.

So I got out of prison and immediately had a job as a paralegal. Blessed, huge. I’ve never been close to making that having that sort of life or that sort of purpose, and this motherfucker is trying to get me fired every day. Because if your boss doesn’t answer when they call after two no answers, you’re kicked out of that job. And he’s calling them 8am, 8:50pm, random times trying to set them up, so I could get fired, because he hates seeing people succeed. You might have experienced it as well. The people at the halfway house are not our friends. They’re not there to lift us up. They’re there to hold us until we go back into the system. That’s all it is. It’s a very, very low-security prison. And if you don’t have support, if you don’t have emotional support, like bro mentioned therapy. I have EMDR therapy, and it’s volunteered to me. Who has that? Who can afford that? I couldn’t afford it without help. And so these things that help us mentally, emotionally, and then tangibly to survive, that’s the difference between going back inside. I’m still on probation right now. I had to get permission from my probation officer, from the judge, saying I was going to be at this place at this time around these people, Jake was going to be here. I was going to be here. I had to get permission for that. By name. They would look them up and say, “What are you guys going to talk about? Are there any rabbits involved? Like, what’s going on?”

Jake: Yes. There are labs here. Primate labs, rabbit labs…

Eric: Are you serious?

Jake: We’ve got a primate lab here, like 1000 monkeys put in cages away from their mothers.

Eric: I was trying to be silly.

Jake: It is a federal lab. Not even maybe productive science uses.

Eric: Well, that’s fucked up…

As I was saying, support people when they are out of prison. Be there for people. When you see someone getting out, trust me, they need something. It might be shoelaces, might be an old pair of shoes, might be glasses. They need something. It might be someone to talk to. Might just be someone who can listen to them cry. But they need help, and it doesn’t take much. So on the back of what Jake said, and thanks for your wonderful question, that’s what I would really recommend. Understand that we need help, just like we need help on the streets.

Host: Thank you, Eric. I want to shift gears to a topic that’s going to be somehow a little bit more brutal. Sometimes, there’s a narrative around race, whiteness, and white supremacy specifically, in gang culture and prisons. Oftentimes, the narrative is that white folks, especially white men, have to assimilate and join some white power, Aryan Brotherhood, white supremacist prison gang if they are able to survive their prison sentence. There’s a short history of maybe one or a couple people who have gone into prison not a member of a white supremacist organization and come out a member of a white supremacist organization, people from radical circles, people not. I’m curious as two white ex-prisoners, what are your answers when you are confronted with this narrative that as a white guy in prison, you have to join the Aryan Brotherhood to make it through?

Eric: Just so everyone knows, the Aryan Brotherhood in the feds is a very exclusive club. You are not joining it. It’s called the Brand. There are only 30 of them, like 18 of them are in ADX, these old motherfuckers with big white mustaches. You’re not joining that gang. But in my experience—I was in a little later than Jake, so things might have been different—when you enter prison, you are entering as your race. You cannot separate them. And if you try to separate from it, you will leave prison missing parts of yourself. If you’re white you will join a car. You won’t have a choice about this. In my case, it was a Missouri car, Kansas City. A car is an organized group that you sit with, work out with, and eat with. You can still be friends with everyone else and kick it with them. But when I ate breakfast, lunch, and dinner, I was sitting at the Missouri table exclusively on the right side with the Kansas City bros. And it’s the white table, and then over there’s the Natives, over there’s the Blacks, over here’s the Southern California, over here is Paisas. You’re not going to get away from that. I had to live with white guys. I had to eat with white guys. I had to workout with white guys. If I shared a cup of coffee with a Black guy, I was going to get stabbed. That’s how it is. Those are things you cannot help. And if you try to push that line, it’s going to push back, and it’s going to push back with steel. You’re going to get chopped up. So there are lots of times where I would try to navigate it in very peculiar ways.

At least at Florence in the pens, you go teach classes and have other races in your classes. So I would teach a yoga class and let the gay roll in, let the Black roll in, welcome these people that I wasn’t traditionally allowed to be with. And then I’d go back to my cell and I get jumped by the ACs. ACs are Aryan Circle, a Texas white power gang. And that was how it goes, once or twice a week, I had to fight these motherf*ckers. And it became very normal. “Are you going to let these n-words stay in your class?” “Yes, I am, motherf*cker!” And then it goes, and that’s how I did my time, and it sucked, but you can navigate it. Another thing we did, you could gamble with other races. You couldn’t hang out with them at their table or watch their TV, but you could gamble with them. So we would have scrabble tournaments, me and my Black friends, or me and my Paisa friends, and we’d say it’s for money, and their people don’t care. Paisas don’t care if they hang out with white guys. They don’t give a sh*t. But the white guys care. So the Paisas would back me like, “Yeah, we’re betting $10,” and then we’d say it was $10 on the line, and the white dudes would back the f*ck up. They give me space to breathe because I gotta get the white money. It’s gross. It’s gross as sh*t. But if you’re clever and you stay under the radar, you can navigate that sh*t.

And you don’t have to join a gang. You have to go out of your way to join a gang. It is a long process. It involves lots of fighting, lots of stabbing. There’s an initiation period, a novice period. You have to make a conscious decision. You’re never going to be walking around prison one day and this dude comes up to you, “You’re a member of the Brand now.” The people that have that happen to them are people that most likely weren’t feeling validated by the outside world. They felt abandoned. And the people that were making them not feel abandoned were these sh*theads. It was these sh*theads saying like, “You’re strong, you’re brave, you’re cool. I don’t know why people don’t support you. You’re a badass. We got you though. We’re your family.” And they prey on weak and insecure people that are also strong and violent people. When these dudes become gang members, they’re making a conscious decision every day of their lives to become a gang members. And when I fought those Nazis, I was making a conscious decision every day of my life to fight those Nazis. This is just how it goes and you have to decide what’s important to you. And those dudes chose to feel validated more than they chose to feel their ethics. And that’s how my experience was. You were in a very nasty prison. You could talk about that.

Jake: Yeah, like I said in the beginning, I think everyone has different experiences, and that wasn’t quite mine, but it was somewhat similar. In Victorville, everything was segregated, everyone was segregated. It was self-segregated. People were segregated by race. They were segregated by gang, neighborhood, into cars. You had shot callers, you had unit reps who were the people that were the head of like the white rep, the Black rep, and the Paisa rep, and then they all answered to the shot caller. And each unit had a different rep, and it’s a bunch of bullshit. It’s exhausting. But there is an understanding that if you don’t follow the rules to a certain extent, then you will be reprimanded or punished, and it depends on what you did wrong, what your infraction was, or whether or not they just didn’t like you. For me, obviously, I wasn’t interested in any of that bullshit, but I also knew that if you step too far out of line, that resulted in you getting thrown to the ground and your face kicked in by five guys in steel-toe boots, which is what happened quite regularly at Victorville. So it was trying to figure out a way to navigate that.

When you come into prison, if you look different, if you don’t fit the mold, then you are a target for extortion, at least in the prison that I was in. So as a guy who is not covered in tattoos, I’m not exactly the most muscular guy. I was like the scrawny, vegan kid. And they’re all like, “Who the fuck is this guy?” As I came in, I was swimming in my orange jumpsuit. I’m immediately a target for extortion, and you get asked some very pointed questions when you come in, essentially where did you come from? Where did you transfer from? Because you don’t start in a prison like Victorville, but I did, that made me unusual as well. I didn’t come from anywhere. I started here. “What do you mean you started here? What are in you for?” Here’s a question that’s very loaded. They want to make sure you’re not a child molester. They want to make sure you’re not snitch. If you’re one of those two things, you’re going to get stabbed or worse. But you can’t say, “Well, I’m not these things,” and then come up with something. They want proof, and so you have to have your legal documents, which the Bureau of Prisons is now made illegal or not appropriate for you to have because too many people were getting stabbed at places like Victorville and the places that you were at. So you had to prove that you weren’t these things. And you basically had to show that you knew what you were doing. And you also had to show that you were down for your car, and that meant you were going to follow the rules. You were going to ride with your car. If there was someone who needed to be disciplined, you, you, and you, you got to go do it. If there’s going to be a riot, we all got to go out to the yard, and you got to be a part of it. These are things I tried to avoid. Might come as a bit of a shock, but these are the things I was not interested in. I got out of it interestingly, because they’d be like, “Alright, you gotta go beat this guy up?” and I would be like “Dude, I’m the vegan. I’m not very strong. I’m not gonna be able…” “Alright, brother, you watch the door while we take care of this motherf*ckers.” I’d stand outside the door like, “I’ll watch for the cops, sir.”

You did have to have a little bit of creativity in order to get around it. And for me, the things that helped me was one, I took my case to trial. The feds win 95% of their cases. So most people take a deal. It doesn’t mean they’re cooperating deals, but most people take deals. So the fact that I took it to trial made me different than most people, but in a good way. The fact that I didn’t snitch on anyone, that I could prove it with my paperwork, was a big deal, that I went to trial and didn’t snitch at anyone. And there were ways you could answer those questions, like “How much time did you get? Well, I only got four years in a place where people are doing life sentences or 20-30 years. I’m short to the door, which is kind of disrespectful. So I’d be like, “My federal sentencing guidelines had me at 11 to 13 years, and they wanted me to snitch, and they offered me five, but I didn’t.” That’s a way you could let people know that I went to trial and I didn’t snitch, and that built respect around who you were.

It was very hairy for me in the first several months. A lot of white power and skinheads, Warhammer skins. And they call themselves AB, dirty white boys. All these white power gangs were jockeying for, “Oh, here’s the new guy. We can exploit him, or we turn them into one of us.” Now, obviously, I wasn’t interested in either, so I would keep my distance, and they would throw insults, and I would keep my distance. These were big dudes with swastika tattoos. I wasn’t a threat to them, but they wanted something from me, and I was able to push it off long enough where I could get enough respect from the people, not just in my car, but the people in my unit. And that meant I was able to do things that most people weren’t. I was able to share food with Black people. I was able to have people from different races and different cars into my cell and shut the door, which is something you’re not really supposed to be allowed to do by inmate culture, at least in the place I was at, and have conversations. I had all sorts of interesting conversations because I was able to get enough respect to be able to do those things. And that’s how I survived, by building those levels and becoming friends, genuine friends.

I met all sorts of people, people I probably wouldn’t be friends with on the outside. But a lot of these folks just wanted someone to listen to them. They wanted someone to understand and to have an ear to talk to. And so when they close the door and we talk about gang politics, “Oh, your buddy down there?” “Oh, yeah, he’s 12th Street. Like, if I saw him on the street, I would shoot on sight.” I’m like, “But you guys work out and hang out all the time.” “Oh, I would shoot him on the outside. Inside, we’re friends. We’re on the same team. We’re Sureños. We’re the foot soldiers of the Mexican Mafia. On the street, he is my enemy, and I would kill him.” And I would be like, “What about all the money you make on the streets. Have you thought about using those to buy bikes for the kids in your community that you care about?” “I never really thought about that.” Or having gang members come to me and be like, “I don’t know how to read. You mind if I practice reading?” They felt safe, they felt like they had someone who would listen to them, and that got me a lot of respect with everyone. I made genuine friendships with people who, according to prison politics, should be my enemy. That felt really important to me. That was the way I wanted to do my time, and I fought really hard for that, and it worked in my favor. Oh, I got transferred to the lower-security prison. There was that level of institutionalization, I embraced that feeling where I wanted that as part of my experience for some reason. I’ll stop there. There is a level of institutionalization that comes from being in those environments. And it takes hold of you really quick, and it goes back to that prisoner support. It takes a lot of support for people on the outside who care about you to break you of that, and that is another reason that I value prisoner support so much.

Host: Thank you guys.

. … . ..

Transkript auf Deutsch

Host: Okay, alle zusammen, wir fangen an. Vielen Dank, dass Sie an einem Dienstagabend zu dieser Veranstaltung gekommen sind. Das Wetter ist schön draußen. Du könntest da draußen sein. Aber ich möchte Sie alle willkommen heißen und unseren Gastgebern Eric, Jake und Josh meinen Dank aussprechen. Ich gebe ihnen die Chance, sich vorzustellen. Zuerst werden wir ein wenig von dem machen, was die Leute in der Theaterbranche meiner Meinung nach Housekeeping nennen. Daher handelt es sich bei dieser Veranstaltung zunächst einmal um eine Spendenaktion für den Internationalen Tag der Solidarität mit antifaschistischen Gefangenen am 25. Juli. Diesen Tag der Solidarität gibt es nun schon seit vielen Jahren, und obwohl der Tag auf den 25. Juli fällt, konnten wir diese Veranstaltung nicht am selben Tag durchführen, also haben wir sie um eine Woche verschoben. Keine große Sache. Auf dem hinteren Tisch steht ein Geldglas. Sie können sowohl Geldspenden als auch in das registrierte Venmo-Konto einzahlen, über das Sie elektronische Spenden senden können. Dieser Venmo ist IADF206. Der Internationale Antifaschistische Verteidigungsfonds wird dieses Geld erhalten und es dann an Dutzende antifaschistische Gefangene auf der ganzen Welt verteilen, die wegen verschiedener antifaschistischer Verbrechen eingesperrt sind. Bei dieser Veranstaltung werden wir über Gefängnisse, Gefangene und politische Gefangene sprechen und dies auch als Möglichkeit nutzen, finanzielle Unterstützung für Menschen zu bekommen, die derzeit wegen des Kampfes eingesperrt sind. Bevor wir jedoch weiterkommen, möchte ich jemanden von einer Unterstützungskampagne für eine örtliche anarchistische Gefangene namens Amber Kim einladen, vorbeizukommen und uns ein kleines Update darüber zu geben, was mit Amber los ist.

Morgan: Okay, hallo, mein Name ist Morgan. Ich bin hier, um über meine Freundin Amber zu sprechen, eine Transfrau im Washington State Prison. Vor etwa einem Monat wurde Amber von Wärtern geschlagen und gewaltsam von einer Fraueneinrichtung, in der sie die letzten vier Jahre verbracht hatte, in eine Männereinrichtung verlegt. Das DOC begründete dies damit, dass sie im Gefängnis einvernehmlichen schwulen Sex mit anderen Personen hatte. Den meisten Menschen ist wahrscheinlich bekannt, dass es im Gefängnis ständig zu schwulem Sex kommt, und als Transsexuelle ist Amber nun einem ernsthaften Risiko von Belästigung und weiterer Gewalt im Männergefängnis ausgesetzt. Die andere Person, mit der ihr dieser Verstoß vorgeworfen wurde, wurde nicht in eine andere Einrichtung verlegt. Sie wird ganz offensichtlich diskriminiert, weil sie eine Transfrau ist. Dies ist unseres Wissens das erste Mal, dass das DOC eine Transfrau aufgrund eines Verstoßes aus einer Fraueneinrichtung verlegt hat. Dies schafft einen wirklich gefährlichen Präzedenzfall für Transfrauen in Gefängnissen des US-Bundesstaates Washington. Ich wollte ein Zitat von Amber teilen. Dies ist aus einem Artikel, den Victoria Law vor Wochen in Truthout geschrieben hat. Amber sagte: „Das Wichtigste, was ich bedenken muss, ist, dass ich kein Ausreißer bin. Es ist mir gelungen, die Aufmerksamkeit auf das zu lenken, was normal ist. Der Einsatz staatlich sanktionierter Gewalt, um Menschen in unsichere Situationen zu zwingen, ist für das DOC normal. Die Missachtung des Sicherheitsverständnisses einer Person ist für den DOC normal. Die Diskriminierung von LGBTQ-Personen ist für das DOC normal. Ich bin nichts Besonderes. Ich hatte zufällig etwas Glück, die Aufmerksamkeit auf dieses Problem zu lenken.“

Deshalb saß Amber in den letzten Wochen in einem Männergefängnis in Einzelhaft. Sie beendete einen 17-tägigen Hungerstreik, und von außen führten viele Menschen wöchentliche Aufrufe durch, um sie zu unterstützen, und schickten Briefe an sie und an das DOC. Wir versuchen wirklich, uns rund um dieses Thema zu organisieren, weil Amber äußerlich vielen von uns sehr nahe steht. Ich bin seit sechs Jahren mit ihr befreundet. Viele andere Menschen sind seit vielen, vielen Jahren mit ihr befreundet, und sie hat sich im Gefängnis sehr hart für andere Transfrauen eingesetzt. Das ist einer der Gründe, warum wir uns stark für sie einsetzen, aber auch, weil dies wirklich ein Lackmustest dafür ist, wie viel Gewalt sie im Gefängnis gegen Transfrauen anwenden können, und um zu sehen, dass sie dies auch in Zukunft anderen Frauen antun können. Deshalb bemühen wir uns wirklich sehr, dass die Leute jetzt auftauchen und ihnen mitteilen, dass sie versuchen, dies auch anderen Transfrauen anzutun, und dass die Leute großen Aufruhr darüber machen werden. Wir bitten Sie heute, zwei Dinge zu tun, um uns zu helfen. Das erste ist, wenn Sie Instagram haben, können Sie unserer Support-Seite auf Instagram folgen. Sie können Ihr Telefon herausnehmen und es ist @Support4AmberKim, und es gibt dort ein paar Flyer, auf denen auch diese Informationen stehen. Die andere Sache ist, dass auf der Rückseite ein paar Postkarten liegen, die die Leute gerade herumreichen und die an Cheryl Strange gehen, die erste offen schwule Sekretärin des DOC, und die Amber während der Pride Week in eine Männerklinik geschickt hat . Offensichtlich wissen wir, dass schwule Menschen an Orten mit Macht nichts für uns tun, deshalb versuchen wir Cheryl wissen zu lassen, dass die Leute auf diese Situation achten, damit wir hoffentlich Druck auf sie ausüben können, sie in die Fraueneinrichtung zurückzuschicken. Sie können die Karten dort hinten am Tisch abgeben, wir stempeln sie dann ab und verschicken sie. Das ist es. Vielen Dank euch allen.

Host: Bevor wir weitermachen, möchte ich hier auch ein kurzes Update zu einigen lokalen Gefangenenfällen geben. Menschen, die vor dem Aufstand im Jahr 2020, nachdem die Polizei George Floyd ermordet hatte, anderswo im Land eingesperrt waren. Die erste Person, über die ich sprechen möchte, ist Tire Means. Er wurde verhaftet, angeklagt und zu mehreren Jahren Gefängnis verurteilt, weil er während des Aufstands am ersten Tag der Unruhen dabei geholfen hatte, ein Polizeiauto niederzubrennen, und anschließend einem Polizisten die Schusswaffe vom Heck gestohlen hatte. Ich bin seit Jahren ein Brieffreund von Tyre, seit er eingesperrt wurde, und durch unsere Freundschaft habe ich herausgefunden, dass Tyre ein wirklich lieber Mensch ist, der auch voll und ganz an eine allgemeine Volksrevolte gegen die gewalttätige weiße, supremacistische Polizei glaubt. Er ist ein wirklich süßer Junge. Derzeit ist er in Victorville in Kalifornien eingesperrt, nachdem er in Texas in einem Gefängnis, das vor Ort als Bloody Beaumont bekannt ist, ziemlich heftigen körperlichen Belästigungen ausgesetzt war. Deshalb ermutige ich Sie alle, Tyres Namen in Ihrer Erinnerung zu behalten. Und ich gebe Ihnen eine Vorstellung davon, wie Sie an seine Adresse gelangen. Du kannst ihm später schreiben. Er ist bei USP Victorville. Und dann möchte ich noch Marge Shannon hervorheben, die eingesperrt wurde, nachdem sie Fotos in den sozialen Medien identifizierten, dass sie dafür verantwortlich war, im Jahr 2020 auch ein Polizeiauto in Brand gesteckt zu haben. Ich möchte diese beiden Personen hervorheben, die wegen ihrer Aktivitäten in verschiedene Gefängnisse vor über vier Jahren verhaftet wurden und immer noch im Gefängnis sind. Und viele Menschen sitzen immer noch im Gefängnis für das, was sie während des Aufstands von George Floyd im Jahr 2020 getan haben. Deshalb möchte ich Sie alle ermutigen, diese Namen, Tire Means und Marge Shannon, in Ihrer Erinnerung zu behalten und auf uprisingsupport.org zu gehen, um ihre Adressen zu finden So können Sie Post schicken und die Adressen von vielen, vielen weiteren Personen finden, die immer noch eingesperrt sind.

Okay, jetzt, da wir mit der ganzen Hauswirtschaft fertig sind, heißen wir unsere lieben Gäste willkommen. Wir haben Jake Conroy, der an dem Buch Rattling the Cages mitwirkt, und dann haben wir Josh Davidson und Eric King, beide Herausgeber dieses schönen, umfangreichen Bandes, den jeder lesen sollte. Und Eric King ist ebenfalls Mitwirkender. Geben wir ihnen also einen Applaus. Habt ihr Lust, kurze Einführungen zu machen? Ja, fangen wir mit Jake an.

Jake: Alles klar. Wie kurz?

Host: 15 Minuten? Ich werde dich anschreien.

Jake: Was möchtest du wissen?

Eric: Name, Verbrechen … [Gelächter]

Jake: Perfekt. Mein Name ist Jake Conroy. Ich lebe hier in der Gegend von Seattle. Ich wurde zu 48 Monaten verurteilt. Ich verbüßte 37 Monate in zwei Gefängnissen, eines in Victorville, einem Gefängnis mittlerer Sicherheitsstufe. Das ist ein Gefängnis-Industriekomplex, also gibt es insgesamt vier Gefängnisse: zwei Medien, ein Gefängnis und ein Frauenlager. Und dann wurde ich nach Terminal Island verlegt, einem Niedrigsicherheitsgefängnis, einer Insel im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes im Hafen von San Pedro, Los Angeles. Ich spreche eine Stunde lang über meinen Fall und die Zeit, als ich im Gefängnis war. Ich werde versuchen, es auf etwa zwei Minuten zu verkürzen.

Im Grunde führten ich und einige Freunde eine Druckkampagne gegen ein Tierversuchslabor durch. Oberflächlich betrachtet hatte die Kampagne ihre Wurzeln stark in den Tierrechten, aber im Kern ging es in Wirklichkeit um den Kampf gegen den Kapitalismus, weil wir nicht gegen dieses riesige Labor protestierten. Wir protestierten gegen jeden und jeden, der damit in Verbindung stand. Also haben wir gegen die größten Banken der Welt, die größten Pharmaunternehmen der Welt, die größten Versicherungsunternehmen der Welt, die Wirtschaftsprüfer und alle anderen, die damit in Verbindung stehen, Aktionäre und Börsenmakler protestiert. Wir waren bei Protesten gegen die New Yorker Börse. Wir konnten im Wesentlichen über 100 der größten Unternehmen der Welt dazu bringen, das zu tun, was wir wollten, nämlich die Finanzierung und Unterstützung dieses Labors einzustellen. Wir haben dafür gesorgt, dass sie von der New Yorker Börse verdrängt wurden. Wir haben ihren 30-Dollar-Anteil genommen und ihn auf einen Wert von etwa zwei oder drei Pennys gebracht, und wir haben dieses Unternehmen lahmgelegt. Und mit „wir“ meine ich nicht unbedingt mich und meine Freunde, die diese Organisation namens SHAC gegründet haben, sondern diese globale, basisdemokratische, nicht hierarchische Bewegung, die sich auf jede Art und Weise beteiligen konnte, die sie wollten.

Wenn man einen so großen Einfluss auf den Kapitalismus hat, wird die Regierung darauf aufmerksam, und natürlich auch das Unternehmen. Wir wurden 23 Mal verklagt. Gegen uns wurde eine bundesstaatliche RICO-Zivilklage in Höhe von 12 Millionen US-Dollar pro Stück eingereicht, und schließlich verhafteten sie sechs von uns und beschuldigten uns verschiedener Anklagepunkte. Das wichtigste hieß „Animal Enterprise Protection Act“, das jetzt „Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act“ heißt. Dabei handelt es sich um ein Gesetz, das speziell für Tierschützer geschrieben wurde, die durch das Land fahren, Laboratorien und Pelzfarmen überfallen, Tiere freilassen und sie zerschlagen sie. Und das Gesetz besagt: Wenn Sie die Staatsgrenzen überschreiten und ein Unternehmen stören, das Tiere verwendet, und mehr als 10.000 US-Dollar für den physischen Schaden am Eigentum verursachen, können sie dich als inländischen Terroristen vor Gericht stellen. In unserem Fall sagten sie, wir hätten über das Internet Staatsgrenzen überschritten, weil wir uns online organisiert hätten. Der Online-Organisationsbereich war neu. Das war von 2001 bis 2006, aber nichtsdestotrotz haben wir mehr als 10.000 US-Dollar für die Wirtschaftssabotage bzw. den wirtschaftlichen Schaden an diesem Unternehmen angerichtet, und deshalb wurden wir alle unter dieser und einer Reihe anderer Anklagen für schuldig befunden. Ich wurde, wie gesagt, im Grunde genommen zu 48 Monaten Haft als inländischer Terrorist im Bundesgefängnis verurteilt. Und so habe ich meine Zeit verbracht.

Eric: Mein Name ist Eric. Dies ist das erste Mal seit meiner Veröffentlichung, dass ich außerhalb von Colorado spreche, daher bin ich sehr aufgeregt. Ich freue mich, dass Sie alle kommen. Ich wurde vor sieben Monaten freigelassen, nachdem ich etwa zehn Jahre wegen eines Brandanschlags auf das Büro eines Kongressabgeordneten aus Solidarität mit dem Aufstand in Ferguson, nachdem die Polizei Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, getötet hatte, zu einer Haftstrafe verurteilt worden war. Meine Gemeinde in Kansas City hat die Verantwortung nicht übernommen. Nachdem ich also für ein paar Tage nach Ferguson gefahren war und gesehen hatte, was diese Menschen durchmachten und welches Risiko sie eingingen, um ihre Gemeinden zu verteidigen, hielt ich es für meine Pflicht, mich ihnen in diesem Kampf anzuschließen. Also tat ich, was ich tun musste. Am Ende habe ich neun Jahre und sechs Monate oder so einen Scheiß verbracht. Ich wurde vor sieben Monaten aus dem Federal Supermax ADX entlassen, wo El Chapo ist, wo all diese Wichser sind. Ich habe es dort etwa zwei Jahre lang gemacht. Ich bin einer von nur wenigen Menschen, die jemals alle Sorgerechtsstufen in Anspruch genommen haben. Ich begann bei niedrig, dann mittel, dann Gefängnis und schließlich Supermax für den Widerstand im Gefängnis. Ich bin so froh, dass ihr alle hier seid. Danke schön.

Josh: Und mein Name ist Josh. Ich war noch nie im Gefängnis, aber in den letzten etwa zwölf Jahren habe ich die meiste Zeit damit verbracht, Menschen zu unterstützen, die im Gefängnis sind oder waren. Ich bin Mitglied des Kalenderkollektivs „Sichere Tage: Freiheit für politische Gefangene“, das seit 25 Jahren Geld sammelt und das Bewusstsein für politische Gefangene schärft. Und ich habe dieses Buch, Rattling the Cages, zusammen mit Eric herausgegeben. Es war seine Idee, als er beim ADX war, und ich interviewte etwa 40 politische Gefangene mit Fragen, die wir gemeinsam entwickelt hatten. Wir hofften, dass das Buch nicht nur dazu beitragen würde, Spenden zu sammeln und das Bewusstsein für politische Gefangene zu schärfen, sondern auch dazu beizutragen, ihre Geschichten zu teilen und mehr Menschen dazu zu bewegen, sich für ihre Unterstützung zu engagieren.

Eric: Das Beste, was ich je gemacht habe!

Host: Nun, vielen Dank für diese Vorstellungen. Um das in Gang zu bringen. Ich wollte eines der Kapitel in Rattling the Cages von Bill Dunne hervorheben, einem anarchistischen politischen Gefangenen, dessen Haftstrafe tatsächlich hier in Seattle, Washington, begann, als er versuchte, einen Kameraden aus dem Gefängnis der King County Correctional Facility in der Innenstadt von Seattle zu befreien im Jahr 1979. Während des Jailbreak-Versuchs kam es zu einer Schießerei zwischen der Polizei von Seattle und dem Auto, in dem Bill und zwei seiner Kameraden saßen. Seitdem hat Bill mindestens einmal versucht, aus dem Gefängnis auszubrechen, und seine Bewährung wurde 2014 aufgrund seiner politischen Überzeugungen und seiner Weigerung, den Anarchismus zu verleugnen, abgelehnt. Bill befindet sich derzeit in einer medizinischen Einrichtung, um sich einer Krebsbehandlung zu unterziehen. Sein Kapitel in dem Buch fällt mir auf, nicht nur, weil er es hinter Gefängnismauern geschrieben hat, sondern auch weil er ein langjähriger Gefangener ist, der den Kampf seit über 40 Jahren prinzipiell führt. Er normalisiert fast die Zustände im Gefängnis, während er seine Zeit dort detailliert beschreibt, was meiner Meinung nach wichtig sein kann, um Leser, die noch nie im Gefängnis waren, daran zu erinnern, dass der Kampf nicht aufhört, wenn man ins Gefängnis kommt, sondern weitergeht. Wie haben Sie drei, die an diesem Buch beteiligt waren, die Worte von Bill und anderen Ältesten in dem Buch angenommen? Was war für die Herausgeber wichtig, als sie die Worte von Bill Dunne und anderen Ältesten einbezog?

Eric: Ich werde versuchen, nicht zu langatmig zu sein. Deshalb habe ich Bill und unsere Ältesten schon lange bewundert, bevor ich eingesperrt wurde. Das sind die Menschen, die mich motiviert haben, diesen Kampf auf die Art und Weise voranzutreiben, die ich für am angemessensten hielt, nämlich auf die Art und Weise der direkten Aktion. Und ich lernte einige der Ältesten kennen und hörte ihre Geschichten über ihren Widerstand, über ihre Weigerung, vor diesen Polizisten den Kotau zu machen. Darüber, dass wir nicht aufgehört haben, uns am Kampf zu beteiligen, dass wir eine andere Front vertreten haben und dabei oft auf uns allein gestellt sind. In den meisten Fällen sind keine anderen Anarchisten, Antirassisten oder Antifaschisten dabei. Es stellt also Ihre Ethik und Ihr Engagement für diesen Kampf aufs Spiel. Es zeigt wirklich, worum es dir geht? Und diese Typen haben mich wirklich, wirklich vorangebracht. Und ich benutze Jungs auf eine nicht geschlechtsspezifische Art und Weise. Wenn es jemanden beleidigt, entschuldige ich mich. Und bitte, bitte rufen Sie mich an. Aber wenn man diese Leute sieht, die seit 20 oder 30 Jahren im Gefängnis sind und die eingesperrt waren, als diese Gefängnisse in Aufruhr waren, dann wurden sie eingesperrt, als es brutal war. Das ist es immer noch, aber es gibt Stufen. Und zu sehen, wie sie nicht nur nicht nachgeben, sondern auch in ihrer Ethik wachsen, in ihrem Geist wachsen, in ihrer Solidarität und ihrem Engagement für diese Bewegung wachsen. Wenn du dir das ansiehst und darüber liest, wenn du jemandes Buch in die Hand nimmst – so wie ich bei Dan Bergers Buch bin oder so – und du diese Geschichten liest, feuert dich das an und es zeigt dir, dass es sich lohnt. Und ich kann Angst haben, aber ich kann trotzdem weitermachen, und es ist nicht anders als auf der Straße, aber drinnen muss man es wirklich finden. Man muss es wirklich wollen. Und die alten Katzen haben mir dabei wirklich geholfen.

Jake: Ich möchte mich dafür bedanken, dass ich dabei bin. Ich möchte Eric noch einmal applaudieren. Ich finde es bemerkenswert, dass Sie hier sind. Es hebt wirklich meinen Geist. Ich bin begeistert. Applaus. Ich freue mich, Sie hier zu sehen. Es ist eine schwierige Sache. Wir alle haben unterschiedliche Erfahrungen damit, wenn wir im Gefängnis sind. Jeder hat seine eigene Geschichte und keine davon ist einfach. Manche mögen schwieriger sein als andere, aber am Ende des Tages weiß niemand wirklich, was es für die betreffende Person bedeutet und was sie während ihrer Inhaftierung hinter Gittern durchgemacht hat. Ich kenne nicht alle deine Geschichten. Ich kenne nicht alle deine Erfahrungen. Ich kann es mir nur vorstellen und komme wahrscheinlich nicht einmal annähernd an das heran, was sie waren. Die Tatsache, dass Sie hier sind und sich zu den Dingen äußern, die Ihnen am Herzen liegen und für die Sie Leidenschaft empfinden, wärmt wirklich das Herz. Und ich schätze dich. Also vielen Dank.