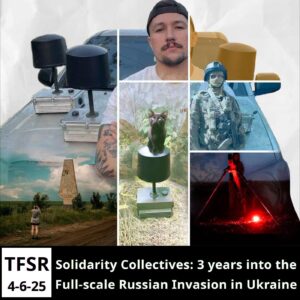

This week, we’re featuring an interview with Anton, a longtime member of Solidarity Collectives, a group that supports anti-authoritarian and anarchist activists involved in the resistance to the Russian invasion of Ukraine as well as funding mutual aid projects for civilians and domesticated animals suffering or displaced by the invasion, bolstering left libertarian social movements during wartime, making propaganda and manufacturing FPV drones as well as a few other projects.

In this ranging conversation we spoke for 2 hours covering issues of anarchists participating in military structures, the state of the armed resistance, impacts of changes in the US administration and more.

Solidarity Collective Links:

- Website listing ways to support different sectors of work: https://solidaritycollectives.org/en/support/

- youtube and kolektiva channels, with interviews of comrades fighting and yearly reports of activity playlists:

- Libcom blog: https://libcom.org/tags/solidarity-collectives

Sol Col socials:

- mastodon: https://social.edist.ro/@solidaritycollectives

- bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/solcolua.bsky.social

- telegram :https://t.me/SolidarityCollectives

- instagram: https://www.instagram.com/solidaritycollectives/

- Twitter: https://x.com/SolidarityColl1

- FB: https://www.facebook.com/SolidarityCollectives

Anton’s work related socials:

- bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/antonkolcol.bsky.social

- mastodon: https://social.edist.ro/@anton_tsak@kolektiva.social

Other Links:

- Past interviews on Ukraine: https://thefinalstrawradio.noblogs.org/post/category/ukraine/

- Timothy Snyder about Ukrainian history : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bJczLlwp-d8&list=PLhTRXzDqRJxjwJVIddAFOF3Eg8OESGiSM

- Comrades reviewing far right violence activities in Ukraine since 2018: https://violence-marker.org.ua/en/

Media About the 3 Internationalist Anarchists Who Fell April 19, 2023:

- Dmitry Petrov was interviewed under a psuedonym on this episode of our show: https://thefinalstrawradio.noblogs.org/post/2022/02/25/anarchists-in-ukraine-against-war/

- Memorial page on Crimethinc for Dmitry: https://crimethinc.com/2023/05/03/in-memory-of-dmitry-petrov-an-incomplete-biography-and-translation-of-his-work

- Documentary on Finbar (English subtitles available): https://www.tg4.ie/en/player/home/?pid=6347744855112

- Remembering Cooper Andrews: https://itsgoingdown.org/remembering-cooper-andrews/

… . ..

Featured Track:

- Не забудем і не пробачим (“We Wont Forgive and We Won’t Forget) – SKOFKA

. … . ..

Transcription

TFSR: Would you please introduce yourself with any names, pronouns, locations, or identifying information or affiliations you’d like to share with the audience?

Anton: Yeah, hello. I’m Anton. I use he/him pronouns, I’m in my early 40s, and I’ve lived in Kyiv, Ukraine, for two and a half years. But I’m not Ukrainian. I’m originally from Eastern Europe. I also have a history in my family of displaced people from other wars with Russia in the past.

TFSR: Cool. Thank you so much for having this chat. Can you share a bit about how you became politically radicalized or an anarchist? What sorts of work outside Solidarity Collectives have you been drawn to, and how do you identify politically?

Anton: It’s now been about 15 years that I’ve been organizing in the European anarchist movement, broadly in different places. Previously, I was working in low-paying jobs. I didn’t have the opportunity to attend university. My radicalization came later on in my life by meeting friends and comrades that I still have today. I’ve also been active in anti-fascist struggles in Europe, specifically following for the last 15 years the funding sources, such as those from Russia, that support far-right parties in Europe. I was aware of this situation in 2022, which is why I decided to become active in this struggle here. I’ve also been organizing mutual aid networks; the last one was during the COVID-19 pandemic. My general views are that patriarchy is one of the main pillars that I see for building capitalism and the state. I actively try to fight patriarchy as well. I believe this is how I can present myself politically.

TFSR: Would you mind sharing your experiences of the full-scale invasion and war and how you became involved in Solidarity Collectives?

Anton: Yeah. At the beginning of February 2022, when there was the gathering of troops from the Russian side along the Ukrainian border, my impression was that this would be a total invasion because of the number of troops and that this would be a war that would last for the next 10 years, with a lot of escalations. This stems from my understanding of the relationship between the far right in Europe and Putin’s Russia, particularly in terms of funding and political alignment. When the invasion started on February 24, I was in Europe. Through friends and comrades interested in what was happening, I eventually found myself traveling to Poland to help in the warehouse that the ABC-Galicja, Polish comrades there, had set up. I knew some comrades through some others who were coming to fight. I was I participated in a military service when I was in my 20’s. That’s more than 20 years ago, but I didn’t know exactly what I would do at the beginning. Still, I thought that I would be more useful in supporting and organizing this solidarity network that became the Solidarity Collectives at the time.

Throughout the spring of ‘22, I was between Poland and Ukraine, primarily in Lviv, trying to understand the different networks trying to find each other, and make things work together. From the summer of ‘22, when things became clearer in the sense that there was no longer a need to import everything from Europe, we could find everything in Ukraine at that point. I started to be more active in Kyiv and other parts to drive or continue building the communications. When conflict arose within Operation Solidarity, another comrade from Poland and I served as mediators in a larger discussion involving members of OpSol and some ABC groups. Following this talk, decisions were made among the comrades in OpSol regarding the formation of SolCol, and I chose to work with those from SolCol because I saw the support of all the past activists from Ukraine who had been fighting. Also, comrades who were from the West, Belarus, or Russia. Everybody was joining around this structure. This is how I decided to become a member of Solidarity Collectives at the beginning of 2023.

TFSR: Could you speak a little more about the nature of the conflict or the split between the groups. As I understand it, Solidarity Collectives is obviously much better known because it’s been operating in the meantime as an independent network. However, there are still remnants of the original group that SolCol split from that are still floating around and trying to collect money or do whatever else.

Anton: There is a period I wasn’t directly involved in, but I heard from others that about a week after the start of the full-scale invasion and the launch of Operation Solidarity, many comrades joined the initiative. This led to some problems, mostly related to stress or personal issues including psychological struggles. That built up to the point that there was complete mistrust among many people. After few months the proposal on the table was “Let’s put all the money together and then decide on different projects.” This was refused by three people who had kept their hands on some of the accounts and were bargaining from the position of holding some of the bank accounts. This was considered as not okay; we should put all the funds together and then decide on the different projects. These proposed projects were as follows: one was a secret project that was supposed to last a year, and those who then left couldn’t disclose its details out of mistrust for others. And that’s when it was decided that this was no longer a discussion, it was just a bargain about how much money someone can keep for his secret project.

So from there, it was not a discussion anymore; it was just forcing to – They kept a part of the money because there was a decision not to force them to give everything, and this was related to the situation at the time and also to acceptance of not entering something that would be more about violence between people. That part had then left. They also retained access to some social media, namely Instagram. It was always a thought that there was one story of what I would call corruption, rather than theft, namely using collectively gathered funds for a personal project. During the year after it happened, there were a lot of attacks on what is SolCol, namely on one of our members, and this continued in some chats. This then proved that there is really an aim to hurt the support for the comrades who are fighting because of personal nonacceptance of the decision, at least from one of those who were forced to quit. But it was a decision to make a new group, to start from a new page and this is what happened. But since the time we saw the old Instagram of Operation Solidarity, they changed the name, and it’s still a bit unclear what is going on with this. They want to reuse the number of followers from this page and make it look like an NGO from Ukraine supporting other soldiers, but in reality, it’s reusing the old account and collecting funds through it, and also trying to reuse the work that was done in the time of Operation Solidarity, just because of holding this one social media account. So these are the strategies that have been used. But after the summer of 2022, what happened was clear for everybody in the movement. Sometimes, we hear of someone who has talked to one of those who were forced to leave and shares the impression of persons who believe that there should be some process and that there was no process of justice in the movement. But this is actually untrue. So we never really answer to it, but we answer to it by our actions. There was a process of nearly two months of discussions, starting from more or less acceptable terms, and, in the end, unacceptable terms. And so there was a process and a decision taken as a result of the process.

So today, we continue to try to follow a bit of what’s happening with this in terms of them gathering funds and possible future corruption. There is other stories concerning the ones who were separated from the solidarity structure at the time, that I won’t open here. Things are pretty clear about what happened and the decisions that were taken in the movement here, and we could clarify it also with the movement internationally. Today, for us, it is no longer a problem, we just try to follow that there is nothing new coming as a possible corruption and gathering of donations on their part.

TFSR: Thank you. That story is reflective of things I’ve seen other groups have to contend with. As these fundraising venues… it’s not based on personal relationships, it’s based on positioning online and social media, it’s pretty easy to get confused from the outside about what group is doing what and what their claims are, if they’re making any, about other group is valid, and how much it is personal and whatever. This is an unending danger, I guess, with this mode of fundraising.

Anton: Maybe one thing I can add: One person from the three that were forced to leave actually tries to make it look like something between two men, between him and one of our members. And this was also seen as a very sexist way of seeing what was happening. And it’s unclear sometimes if he actually understood what he did wrong or if he actually believed that he could do whatever he wanted because he’s like a CEO who created something at some point. Sometimes it feels like this. But the key point is that it was seen as sexist behavior – seeing the conflict as if it was only between two men when in the collective, there were and there are many women who have been very active for a long time in the Ukrainian movement, and who were not taken in account, at least by that one side.

TFSR: Can you talk about the group, Solidarity Collectives, that sprung from that conflict and that difference, and how it has developed, and what lessons you’ve learned about this work?

Anton: Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion in February 2022, the goal of the organizing of the solidarity civilian structure has been to support everybody who was known as a past activist of a group in the anti-authoritarian movement of Ukraine. In the beginning, it was confusing to find everybody, but within the next five-six months it became clearer where is everybody. There was also the managing of people who were coming from outside Ukraine to try to help. So this is still part of our activity, our main part. And for this today, we use approximately between 10 and 15,000 Euro per month to answer the requests. Many comrades have been killed since then in action or declared missing, and there are also a lot of people who have joined since then. So we support, I think, now, a bit more people than what it was at the beginning, even counting all that I mentioned.

We have another part of work that appeared from the summer of 2022, which we tend to call the humanitarian side. It came out of the realization that there was some support directed at supporting civilians. Idea was to back it with what is happening with a network of unions and radical left parties in Europe who tried to be in touch with unions here. So what we did is try to continue the communication with unions here. Because some people from Solidarity Collectives were members in unions, student unions, for example, 10 years ago. And so there was contact with the unions here. Until today, we continue to go every month or every month and a half to bring what is asked by union members or union branches from different industries, like railway unions, teachers unions, or a miners union in Dobropillia. I was there by car just two weeks ago. And on this side now, it’s growing in the sense that we can see that there are more and more contacts between unions in the West and unions here to support each other, including politically, because of the situation here, which was always the aim for us. In the same way that we need funds to survive, meaning people who are fighting and the activists of SolCol also supporting the people from unions would help them survive, so they can be politically active. This has been the basic thought that we have as a collective.

A year ago, we also started to build FPV drones and small copters. This came out of the beginning of Trump’s blocking of US military aid. More than a year and a half ago now, the aid came in late June 2024, if I remember right, but it was postponed for a long time. In Ukraine, there was a lot of discussion that we need to be able to produce our own something to replace the artillery shells that we lack. And so we decided to also be active in producing some, and we managed to make a small production system with two other initiatives that started under a year ago. One is SoliDrones, and the other one is Resistance Support Club. Both are making drones and sending them to us. We finalize them, and then we send them to the comrades who are using them on the front line. Another area of activity is, of course, media, and this is part of the work that I’m doing now. And we’ve been making a lot of events internationally, answering questions about the practices of our movement here and what we’re building. We try to maintain social media as much as we can to show our activity and also give activity reports to have transparency. Those are the main parts of our work currently.

We are about 15 people today, which is nearly double what we were at the beginning of 2023, for example. So in two years, we’ve also been growing in the number of people, which has relieved some pressure of the amount of work that we used to have, allowing for doing more and growing in the sense that we also have more donations, we can see that there is more trust that was built by the time with us, so we can grow. And there are ideas to help comrades by building training capacities. This is still ongoing, but we participate in it. So SolCol became a tool of the movement here to be able to support people who are active in the war, support victims of this war, and try to make a point of autonomous production of what is also used as weapons. I’ll just make a correction about the terms that I use. I use the term “war” because I hear it all the time, but here, it’s a defense resistance movement. It’s not really two states that want war in this sense. So, I would use the term helping the Ukrainian resistance and our movement in it.

TFSR: There are a couple of other elements of Solidarity Collectives. I believe you mentioned earlier that when Operation Solidarity, under its former name, was coalescing, and you were finding activists that were around the country, whether involved in military structures or not, I remember when I spoke to a comrade from the Kyiv ABC in 2022 I think, or it might have been one of the other guess on the show, but they were speaking about how people who had been involved in Food Not Bombs were still going out distributing food, finding food. There was a mention that you had of the civilian side of support for people who were living amidst the invasion, as well, where possible, distributing food, healthcare, and other such things. That’s one aspect you might want to speak a little bit more about, too. Also, there are people who have been killed or displaced by the war, and Solidarity Collectives has a project that’s been going and checking in on and taking care of animals that were domesticated, that were in the care of people that are no longer there. If you could speak about that, too, that’s interesting.

Anton: Right, on the number of people who were displaced, this is an ongoing process because the frontline has been pushed again by the Russian army since autumn of ‘22. And constantly, more people are being forced to leave the place where they are and move west. So, this is an ongoing process. And for example, in Dobropillia, now you have people from Pokrovsk or the villages around who are arriving. So, of course, in this sense, we also follow the initiatives that try to help the newly displaced in the places where we already have made links. That’s what we did on the last trip, for example, to also stop some refugee housing projects to help them out.

About what happened with animals, this is also something that we started doing a year ago because it became obvious since ‘22 that many people, when they left, couldn’t take their animals. Generally, the ones who stayed started to take care of the animals that were left behind. And so we’re trying to help people who made shelters, or are just sheltering in their home in villages the animals of the others who left. So, to help with animal food or any medicine that could be needed for animals as well. What I can clarify about those different “department”s is that for each, we made different donation accounting and accounts so that everybody can specify when they give us to which branch they want to give. This is for transparency and the possibility for people who do not want to help directly with the armed struggle here, for some reason, to help animals, or just by choice, to distribute the funds that one has. Last week, we helped EcoPlatform, which has been helping an animal shelter for a few years. It’s a shelter for farm animals, and they went again last weekend and a member of SolCol also joined the trip. The trip was made from Odessa.

TFSR: That’s really interesting, and I’m glad that you put that out. And that does make sense, for I’m sure that someone in the audience may be very hard anti-militarist, pacifist, or something like that, but care very much about the civilians who are trapped amid this invasion being able to get access to medicine or to food or to whatever support to leave if they need to. Giving the option for that or for supporting the animals that are left behind is very thoughtful.

Anton: Exactly. Also, some structures that might want to help us might have limitations on what they can use their funds for, so having separate accounts for this gave the opportunity to unlock funds to help the civilians or the animals. And this was very good.

TFSR: Also, to the point that you made about the intentionality of the approach in a wartime scenario – and I’ll just use “war” in this case because there is the mobilization of defense troops by the nation state against these and people that are living on the territory controlled by the nation state against an invasion, even if it’s not an offensive war being conducted by one nation against another. We can think about this as more complex than just being Zelensky versus Putin or whatever, a lot more people are being affected by this.

However, also looking at supporting civilian structures, such as unions of various sorts, civil society group and social structures that pre-existed: it’s difficult enough to organize collectively in oppositional ways when there are no bombs and drones flying overhead. So the idea of supporting and sustaining and working with structures that are counter to the state, to some degree, but at least counter to capitalism, counter to patriarchy, and these other values that the state imposes, so that civil society – maybe that’s a liberal term – can continue operating feels like a very important thing that some people that are critical of anarchists engaging in Ukraine while the invasion is going on miss… The idea that if you abandon the oppositional movement, then when the war is over, when the invasion is over, however, that looks, those structures and the social connections with that and the comrades that have been involved in those structures have been abandoned and have to start from scratch, if they’re able to, as opposed to repressive organs that have not persisted throughout resisting the invasion, they are able to take space that was formally held by unions or whatever other social structures. Does this make sense what I’m saying? It makes sense not to cede territory of opposition and organizing.

Anton: Right, that’s what we’ve been expressing since the beginning, that we need the survival of our movement to be active, and this is particular to a situation of a full-scale invasion, with drones in Kyiv flying around almost every day and trying to destroy targets or fall on houses, just like everywhere in Ukraine, this is happening until today. So, on the scale, it’s something particular, maybe for the Western movement that hasn’t experienced a war in the place where they live. So this is our particular experience. The Ukrainian movement was not so different from the European movement in many regards, like the forms of activism and unions, so when people meet, it is very easy to understand each other, what is the focus politically, and what terms are used. So basically, it’s really a mutual aid network that we built for the movement here, and in a situation where we needed support internationally because there was no financial possibility to respond locally, it is not possible for us to just work and use the money from the paycheck to try to make it work. Really huge amounts of money are needed to respond to the situation. So essentially, we’ve been building a mutual aid network with the movement internationally, with the intent of surviving and being active here because we are also active in times of war. We will come back to it a bit later in the podcast about what is the political life today in the war, and this is also due to the work that we’re doing.

So from that, it’s just an acknowledgment of this solidarity that exists in a movement that we’ve seen since 2022. When things were announced, it was a huge amount of money that was actually given, either through ABC Dresden, or through directly Ukrainian structure, or through other structures, and then, with all this money, it was possible to actually organize the survivability of the movement in Ukraine. And in many regards, it worked. The amount of help from this solidarity movement has been huge, and it continues to grow. We also need to think, which is a challenge, as it has been a crazy amount of work to make this work from Ukraine, also with many people from the Ukrainian movement who never had the chance to travel and to meet the movement abroad. So we had to also learn what it means to work internationally. And all this is very new. At least for now, we haven’t found another structure that really works like us in the sense of building all this network that actually works in the case of anarchists who are fighting in a resistance movement very openly, politically like this. So it’s not only about after, it’s also in these times that we can see the effect, and what we can bring also to others is the experience of this. So we’re giving back the experience. And if you look at what’s happening in Eastern Europe, many of the group and comrades are considering the situation and trying to learn about what’s happened here and how to also maybe have tools in case it happens. If you follow, many analysts think it might escalate into more conflict, be it directly at Europe’s doorstep or be it in Georgia, for example. Internationally, things are moving. There are a lot of changes that happen because of this conflict, at least partly because of this conflict that was launched by Putin in 2014 and then escalated in 2022.

For example, the election of Trump, in many regards, I think, is also related to the conflict here and the Russian intent to destroy everything Ukrainian today. I think Trump uses a lot the political intention – the possibility to destroy some people just because you say that they are wrong – which is something that I can also see in what Trump is doing with speaking about Greenland or other places in a way that could lead to a possibility of actual invasion one day. And sometimes things are not taken seriously because he is unstable like that, but I think that should be taken seriously, that the possibility of what happens here actually opens possibilities for others with the same intent to maybe do it in other places, so meaning more conflicts. So, for us, it’s true that this solidarity and this aid network that we’ve been building is something that we see might have been used in other places. Will it be directly with us or by learning from us and then trying to share tools, or will it be by some people who have learned here the tools and the profession or got the experience to actually fight? Could it also help in other places, for example, in Georgia? Those are the things that we are we are also opening as a collective, but also as a movement here.

TFSR: Since 2002, there have been different anti-authoritarian comrades fighting together in or alongside the Ukrainian Armed Forces against the Russian full-scale invasion. Could you speak about some of the experiences of how things have evolved since then, since Black Headquarters, for instance, as a formation? Would you care to share some observations for a mostly Western audience on the complexity and contradictions of anarchists joining into a hierarchical military structure that is authorized by the government? I know that now anarchists and anti-authoritarians participating in the territorial defenses must follow those military hierarchies and orders and find themselves sometimes fighting alongside integrated people that were in the Azov Battalion or other fascist movements or nationalists or liberals or others that they may disagree with or consider to be dangerous.

I guess there are two questions in there, there’s how have anarchists and anti-authoritarians in the military structures and people in SolCol dealt with the complexity of integration into military state structures and the lack of autonomy that points to in terms of getting transferred here, transferred there. And then also contradictions when people are forced to be in battle alongside people with whom they have very strong disagreements or fear while resisting the invasion.

Anton: I don’t want to do this long, but I can start with a short history of anarchists participating in armed conflicts. One example that we’ve been hearing a lot would be Spain in ‘36. Generally, this was after the 40-year-old anarchist union movement and then the birth of the republic. But at this time, all the anarchist militias and some union members accepted to be part of the government. It was part of the newly-born state structure at this time. I’m saying this because sometimes it’s used as a counterargument, but actually, it was not. There was also conscription at this time. After that, you find some 300 Spanish anarchists, for example, liberating Paris together with the American army after the Second World War. More locally here, we have the example of Makhnovschina, where Makhno was making alliances, first with the Bolsheviks, to try to fight off an invasion from Germany. This was even prior to what happened in Spain. So examples of anarchists fighting together, making alliances with whoever has the means to help them defend themselves, and then in potential state structures that were being formed or that were already formed, for example, at the end of the Second World War, or inside the resistance movements in Europe. For example, many anarchists, where possible, participated in the resistance movement. The resistance movements had funds from different states, like the US or the West, but it was also inside Europe. I will close it here for the history, but to live in contradictions means being in action, and anarchist in action is also what’s currently happening in Ukraine. It’s not something specific compared to what happened in the past.

For our situation here, of course, there was not a strong 40-year movement with tens of thousands of anarchists in Ukraine. It was a pretty small movement using tools of opposition that were similar to what you can see in Europe, as I said before. A lot of people had no relation with armed struggle in the sense of a full-scale invasion as we know it since 2022. There was also a part of the movement here that was training since 2014 and some comrades who started to fight in 2014 and 15, namely some comrades from RKAS, which was part of the IWA-AIT (International Workers Association, anarcho-syndicalist) network. So there was an example of some comrades who were already participating in the fight for years, but they were very few. And then there were some others who were participating in trainings that were made for the anti authoritarian left people. But those trainings were in case of invasion or occupation here, so more like a resistance, armed struggle in the context of occupation, and not the type of war that we know since 2022.

So, taking this into account, what were the possibilities? For those who were in Kyiv and others who could join, one thing was organized due to one comrade who was actually fighting for a few years and was already in the army structures, and he could provide the hosting to form one territorial defense unit with around 40 people, maybe a bit more. And there it could be done. This became known outside of Ukraine as the Anti-authoritarian Unit, but it was always linked to the structure, and the territorial defense is also linked to the Armed Forces here. It’s not outside, but it couldn’t do contracts for everybody. So there were some particularities of some people who couldn’t sign a contract, they were like squatters. This lasted until early summer 2022 when everybody realized that they actually had to join other structures because this structure just couldn’t handle them being part of the fighting because this structure was not allowed to move. Also, not everybody could be accepted. This was the situation at the same time.

There were some who were in Kherson and participated in the resistance inside occupied Kherson, also related to the army, of course. And then, when Kherson was deoccupied, they continued the work as trying to defend but in deoccupied territory. This is one example; there are some others who have been in some training since 2015. They were in Kharkiv, and they knew how to use a drone to do photography. So they would take their drone, find the people that they knew were close to territorial defense structures, and just start to use their drone directly to try to watch around, to say where the Russian army was, or try to help with directing the artillery against them. So there were a lot of different ways that people got involved, or that were directly in some units that were involved since the first days in a fight that was something much bigger than what they actually thought would come. Or some in Kyiv that could train for a longer time in this structure I mentioned. So it was in many different ways that people joined the Defense Armed Forces here. At the same time, in 2022, just to put it in a general context, the Ukrainian army was about 300,000 people strong, and in the summer of 2022, it was about a million people. So 600,000 people were not militaries before ‘22. It’s really people who just rushed to the places in which the Armed Forces offered arms and then tried to help with the different tasks that would be needed. And this popular participation in the resistance actually surprised everybody. Also, the fact that the government finally stayed because before ‘22, many people thought they would leave. But actually they stayed, and this created this cooperation between centralization of order and the possibility to organize on a wider scale and the population participating in taking arms. So, from our movement, it was basically the same process with people who were not soldiers but became such along with other Ukrainians. It’s really a popular defense that happened. How did it evolve from there? There were different ideas and different desires. So there were some who were still looking into the possibility of making something that could be an openly anti-authoritarian military structure, of course, linked with the Armed Forces. And this has some specifics. I think the Armed Forces everywhere, in some situations, can try to see what the political or the religious or different group who have the will to fight a certain struggle, and how it’s useful for recruitment for a local army to have people who are convinced that they want to fight.

Soon it will be April 19, a day when three comrades got killed trying to do this. The idea was to do training and participate in some missions to prove combat ability together with a volunteer battalion. Because a volunteer battalion can accept people who are under the recruitment age to join the army, people can be drafted starting from 25 now. It can also take people who are not Ukrainian nationals, which was the case of the three comrades: one was Russian (Dmitry Petrov), one from Ireland (Finbar Cafferkey), and one from the US (Cooper Andrews). So, they went on the first mission with this volunteer battalion. Politically, this battalion recruit from what they call the “radical Christian world.” There is a guy named Karchinsky who is a populist politician, trying to make a political capital of it, but he never could achieve that. He’s not popular as a politician. But he’s one of the people organizing this battalion and has connections in the Armed Forces. This is one example. But the three comrades in this first mission, which had a very high number of people killed or missing in action, it was related to the battle next to Bakhmut, and many bodies were never found. So they are missing officially. So, this was one attempt. But for a lot of other comrades who joined other brigades, they had to sign a contract after the summer of 2022 to be able to be part of the armed resistance here. And it was a very natural choice, it has been the only choice of participating in the armed struggle here. And there is an understanding of what Ukraine is today in the post-US world, a place where people actually have come from Russia and Belarus as refugees for the last 20 years. So it’s clear that in Ukraine, there is nothing that anti-authoritarians should fear from the state; it’s been a safe haven for them in the region. So that’s why many took a decision to fight here because, at some point, you have to fight it off. You cannot just run all the time. Some people who left Russia and Belarus and came here, at some point, you have to do something. For how long will you have to run? And for Ukrainians, sometimes we’ve been hearing why people won’t just leave, which is magical in a way. People tend to forget that all the comrades here have their families here and their friends here. So how are you supposed to just leave everybody you know, possibly under occupation, possibly to die? Of course, everybody would react in a situation that happened in 2022. I would say the contradiction is just about being in action. It’s not a problem. It’s something that you just have to live with when you want to do any political activity. Sometimes, it’s presented as a contradiction in the sense that you shouldn’t do it, which is actually a pretty particular way of using what is contradiction, for me, at least theoretically. So today, all of the comrades have military contracts.

As for working with people they don’t like, either politically or for other reasons, of course, in society, not everybody is an anarchist. So it is very clear that when you enter the armed struggle with an enemy who is just trying to kill everybody around you, be it civilians, be it military. In 2022, nobody has an army contract. So, everybody was a civilian who started fighting, contracts came much later. For participating today in the different brigades, basically, people are mixed with a lot of different people they might disagree politically with, and sometimes maybe they will discuss when they have a chance, and they are not in direct threat of being killed or in action. If there are people with far-right ideas who have not been activists before, they just hold racist ideas or something. I think people talk to each other, but also because of the bond of fighting together, this is what matters most. And then it’s a discussion. As for the activists of the local far-right? There are actually a few, and some can be related to some structures since 2014-15 built on the need for volunteers that has been recuperated by the state, and anybody who has the capacity to recruit would be in the armed forces would say, “Okay, you can be recruited. You are fighting, so okay, you are in this structure.” It has always been recuperated since the beginning, as in my analysis, recuperation from the state of a capacity to recruitment at the moment when it’s needed. For example, some comrades who were fighting in the street when they were younger, with what you would call street Nazis, not politicians, then found each other after 2022. “Oh, you’re a soldier. We are soldiers.” And they just see each other crossing paths in one base or whatever, and it’s like, “Okay, I recognize you. You recognize me. We used to fight each other, but today, you are fighting, obviously on this side, and we are together. What is the work you’re doing? Okay, maybe we can cooperate on this and that in terms of the defense work.”

The problem we have as a collective is we always made clear that we don’t support comrades joining certain structures that are historically connected to the far right. They are actually very few. So it’s very easy to join other structures. It’s a very small part of the Ukrainian Armed Forces in terms of the number of people, and it’s not at all a threat. But also something I can explain, for example, about Azov. Azov Battalion today has some structures related to it, but it’s not politics. It’s army structures. The problem we have with those structures is the politicians, namely the ones who can be in command and try to enter the parliament, for example. This has always been the problem of why we didn’t support it; it was a political question of how the politicians in those structures try to gain benefits from having people join for political gain. About the people today who are in the 3rd Brigade, which is related to people who are there but also politicians or old commanders. And many people who are there just joined because it’s a known brigade that has very good PR and has the reputation also of having better training than if you go to another brigade. Sometimes, some brigades still have training or a command that was taught in the US time, some very specific tactics that nobody wants to be part of. Azov has made a lot of PR to be seen as “we have good training, we take care of our own,” but they don’t do politics in it. They don’t talk about politics with the soldiers. It’s just some people who are in command try to gain from this brigade being known and militarily successful; some gain for themselves. And this has always been our problem, not the people who are soldiers there. You have many different people who join Azov and it’s really just because it’s a known brigade. It’s not because of the politics of certain people who can be there. So the situation is like this regarding the soldiers’ level. Regarding how we’ve been working with it, we do not help soldiers in those units because of some there who try to gain political visibility out of also being in command of some structures. But it’s not directly the soldiers. And in many places, it is like this. Also, in some volunteer battalions or units that appeared back in 2014, it might be difficult for some people to join some structures if they are not Ukrainian. And in some moments, maybe you couldn’t find how to join somewhere, but one volunteer battalion or structure could take you. So some people chose, just because of these practical choices, that it was a possibility just to join somewhere. You could always state your political views, but actually, nobody cares. For those participating in the fight, since 2022 and even before, it’s been very clear that we don’t talk politics inside the army. And it was also an order from the Armed Forces to depoliticize what has been going on since the beginning. But at the same time, they try to use it for different recruitment benefits. This is how it’s happening. It’s really much easier for anybody to join structures that are not related to any far-right politician.

As for what’s happening with the far right in civilian life, I think we come back a bit later in the podcast about the political life here. But in the army, there hasn’t been any problem in the sense of feeling of enmity between people who are fighting together. There hasn’t been a single comrade who said that this has been a problem. It was always like, “Okay, you think like this, I think like this, but we work together.” And it hasn’t gone further. Sometimes, you have some brigades who work together. So, it’s not always the brigade you are part of, but it’s also who your brigade will work with. Sometimes, it can be one support battalion that would be related to, let’s say, the Right Sector, but it would be just trying to work together on a very specific defense or attack. It’s not all about political cooperation. It’s really a military and armed struggle cooperation of fighting together against Russia that is trying to kill everybody here, and it has been a huge understanding since 2022. All the opinions that people can have politically, there hasn’t been really here any activity from the far right based on those ideas, other than like someone could be racist or sexist and say so. In everyday life, sexism exists in the army, but we also have a lot of female comrades who are in the army who explain how it is and how it was for them. Some are commanders today. I guess we will link some interviews on our YouTube that can give more background of the different experiences of many different comrades. It will be interesting to see for people who are following this podcast afterwards. This is what I can say about joining the armed struggle with the Ukrainian resistance linked with the Armed Forces here.

TFSR: Cool. Thank you for that. I can make a parallel to people, maybe not the best parallel, that I’ve spoken to who have gone to prison in the US There are people who join racist gangs inside prison. There are people who, prior to that, were in racist formations that attacked people, for instance, who went to prison. But they’re not necessarily the same people, they’re not necessarily the same motivations for being in those formations. Also, when you’re inside of a larger structure, sometimes you have a critical solidarity with people because you’re both facing a common enemy. That can be a possibility for creating an understanding and helping to broach those conversations like “Your anti-Semitism is fucked up. Let’s work through that.” Also, it doesn’t mean that, after the common enemy is no longer being faced, the conflict between those formerly aligned parties won’t dissolve as well as necessary. So if someone is going to come out of it and still be a fervent member of the Right Sector or one of these other formations, if they’re going to go back to it, there’s no reason that anti-fascists can’t also go back to fighting back against them, too.

Anton: As one of our comrades, Lesik, said already in one interview, he’s an old anti-fascist from here – old like me, I mean. And he was saying, “Today, I’m part of the biggest anti-fascist group in the world, namely the Armed Force of Ukraine.” And he really meant it. Those structures and those politicians, they never really, since 2014, could transform it politically. It’s still under 0.5-1% in the parliament. They don’t exist politically. Most Ukrainians, if you talk to them about this, would tell you they don’t even know what you’re talking about. It doesn’t exist politically. Also, Ukraine has not been a colonizing power or used slaves in history. Because in some places, when people say something racist, it also means that it’s linked to structural racism. This is not the case here. So it’s not the same threat that you would be in France, and the far right is much stronger in France; it’s very strong, even though I am very happy that Le Pen now got judged and found guilty of what she did, which is a good sign. But here, it hasn’t been a political problem. It has been a problem among the youth with some aggression in the street. For this, we have a project named Marker that has been working since 2020 about counting the aggressions linked to sexism or racism. We will put a link to that project, too. And there is a new report about the last year that is coming out soon about the observations of comrades who work on this project of what is the current situation, what’s happening with the organized far right, which is, again, quite small, but existing, it’s true. But compared to the whole of the Armed Forces here, with more than 900,000 people, nobody is scared of the maybe a few hundred that would be maybe plan something for after. There’s no feeling of the threat of anything coming from that, for what will be the Ukrainian society after.

Of course, there are some thematics where they can try to push more like nationalism, these kinds of things. But again, when you use them here, it’s not like if you would use them in the US, or in France, or in countries that were colonizing other places, or if you would do it in Russia. Ukrainians think of it more as a defense, as having a culture that hasn’t been respected and has been tried to be destroyed. It is rather nation-building. So we need to take into account what it means to different people. But of course, we’re trying to give other meanings, like solidarity and cooperation between peoples. But this sounds very natural to people here because of ‘22. Maybe before, there was this thought that there are different parts of society, and not everybody is united. So maybe there were some struggles there on this. But after ‘22, it was like, “Everybody is together. Look, they are trying to kill everybody, all of us here.” So then it became clear that it’s more about solidarity between the different opinions and the different religious and ethnic groupin Ukraine. So there is also a lot of positive that came out of it, in the sense of building this resistance among the people here. And this, I think, is something very important for people to realize that when there are discussions about Ukraine here, it’s very different, historically and politically, from what it would be for the same political movements talking about it in countries that have been colonizing other places. This is not the case here.

TFSR: Thank you for speaking to that. I have more questions, but we’re covering a lot in this conversation, so I think it makes sense to move on. But I appreciate you taking the time and the patience to speak about this.

Some anarchist comrades of mine from countries with histories of occupation or domination by Russia or the US, which was dominated by Russia, have expressed existential dread at the idea of living under Russian occupation. However, to some of the West, the difference between Zelensky and Putin is nil. It doesn’t matter. As they are both capitalist states. Can you speak a bit about what you fear of a Russian occupation and how different it would be from even the wartime life in Ukraine under Zelensky? Are you able to hold a simultaneous critique against both regimes but still recognize differences?

Anton: Ukrainians can be very critical. Here, the political life is very vivid. There is opposition, and there are unions also fighting for workers’ rights. Of course, now there is a set of laws that is related to the emergency state that imposes some limitations on how political struggle can be waged. You cannot organize a march, but you can do a picket. People are using the picket strategy a lot. But on the general level, political discussion is very vivid in Ukraine. The government and the parliament were elected before ‘22, more than four years ago, so if there were not the emergency laws that by the constitution forbid new elections, there should have been an election last year. It cannot be held, and everybody knows why, because it’s constitutional, but there are very vivid discussions. So, actually, some political topics that are related to what’s happening are being thrown into public discussion. Then everybody follows the polls and discussions and then they adapt to this what will be the final voting. And this has been going on now for a year and a half, very vividly on many topics. So, in this sense, democratic life under those conditions has nothing to do with what’s going on in Russia. In Russia, political opposition is being killed, imprisoned, silenced, and forced into exile. That’s why you can find many people in Europe from there, or from Belarus, or actually here, fighting against Russia. The difference between the two is really radical. Today in Russia, if you try to look for any political life, it’s all suppressed or under oppression, or people have been killed or forced into exile. And any organizing is being surveilled and directly under repression. This is still the situation.

As to the fact that both countries are capitalist, today, the whole world is capitalist. Even what is happening in China with the Communist Party is capitalism in many ways. If this would mean that if the whole world is capitalist, then there is no reason for anybody to defend themselves against an invasion. This idea, for me, doesn’t come to any possibility of action in any case. So it’s a very strange idea for me to hear. The Zelensky government is liberal capitalist, it’s evident, and it was evident in their election campaign and what they are doing today economically. But this is not a reason to compare it and apply it to the resistance against the invasion. The political struggle inside Ukraine is happening with the constraints of the situation, namely, having a full-scale invasion in the country, which gives some restrictions by the constitution of what can happen. But of course, a lot of things are thought politically. This is where I say it’s one year and a half that now it’s very active. Because at the beginning, there were members of the Ukrainian intelligence services who were paid by Russia and left Ukraine immediately. Putin’s Russia had paid a lot of people to try to prepare it for a quick invasion and take over the country. This was their goal. But eventually, this was not enough. They could pay some, but it didn’t happen. But still, for a year and a half after that, there was an impression that everyone who speaks up against the government might be a part of an operation financed by Russia. So, in the beginning, it was very difficult to discuss some things because everybody was unsure about how much you could be in opposition without undermining resistance efforts. So, in the beginning, there were a lot of political talks where people were looking at each other, and what happened in 2022 created a lot of paranoia, especially knowing what’s happening in the occupied territories with repression of any opposition there in the same style that is happening in Russia. And people were thinking about the possibility of being active, but without helping Russia. This was the problem. But then, when the front moved east, things clarified a bit on who was who. The trust between people increased, and political life started to be reborn. Today, it’s satire in every sense, like in a healthy democracy. This continues to be the case; people discuss it pretty openly. Of course, there is still this invasion and the war and the trauma of it, so some discussions can be more heated up when you try to push for something. But there are pickets, there are actions, there is also union organizing, feminist organizing, all this is very vivid.

Economically, the government is a liberal capitalist but politically, it is progressive in the liberal sense when it comes to sexual minorities or sexual rights. It needs to be also considered that everybody is now defending together, so it’s okay to respect everybody who is participating in it. So, in this sense, it’s also liberal. There is no repression because of your strictly political ideas. All that can happen here is if there is a doubt or proof that this is actually something that is linked to Russia. And sometimes it’s proved. Sometimes, intelligence services, like everywhere, try to work out what is true or not. So sometimes it’s random something that actually doesn’t come to an end, but there is an investigation. It’s working like this, but politically, we have no fear so far, and we don’t expect having of repression because of our political ideas. And we are very openly an anti-authoritarian anarchist collective attracting more and more attention. Actually, a lot of people here would call themselves progressives just because of the history under the US, of some terms, like left, etc. Even if you would say I am an anti-authoritarian communist, people would get really confused about what you mean because the history with the US has been the history of also Holodomor, where millions of people died, and the history of a colony in many senses. So some terms that we also can use, like “anarchist,” people either don’t know- Everybody knows the name of Makhno, but not everybody knows his ideas, also because of the transformation by propaganda under US of what they made out of Makhno, but everybody knows the popular story about the poor who wanted to take from the rich and share the land. For people, it’s a bit like Robin Hood, but in the general sense, we don’t have a problem as a movement to say this in civilian life or in the army. Comrades have the anarchy insignia or a patch, and some others can have something else, and it’s completely okay; there hasn’t been any attack because of this.

TFSR: Can you speak about the genocidal intent of Russia in this war? For instance, the denial of cultural or political distinction, claiming Ukraine as historically a part of Greater Russia by repeating the phrase “the Ukraine” instead of “Ukraine”? Or, more terrifyingly, material: the forced transfer of 20,000 Ukrainian children in occupied territories and adopting them out to Russian families, assigning them Russian citizenship, sometimes transferring them to holding in Belarus at “summer camps” for russification, which international organizations have noted it’s not just people within Ukraine making this claim, but obviously part of the basis of these charges of genocide that’s being aimed at Russia since the invasion. I wonder if you could speak about this as whether it be as a motivating factor for people to resist or just as a notation because I’m sure there’s a lot that we in the listening audience don’t know about.

Anton: The intent, as I understand it, is also related to how the Russian government today and the remains of what has been told to people inside the US are linked to what we see unfolding today with the situation since 2014, but also earlier. One is this story that Russia would be some kind of federation growing from the US and has been a force of liberation against Nazi Germany. And this is a very strong myth that has been instilled in everybody at school in Russia, very strongly. And in this myth, there is no space for challenging it, and even more, for the Ukrainian culture, and even Ukraine as an autonomous nation, because this would be like losing a limb, basically. If you look into history, one thing that is important for people to follow is there is a full lecture by Timothy Snyder, for example, on Ukrainian history starting more than 1000 years ago. And the links on how Russia was built after it. I think to understand the history, what was done there in this lecture about history is very important for people. If you have a chance, you really should try to find it. It’s on YouTube and really available. It will make you understand the root problem for Russia today with having Ukrainians exist as a separate entity, separate language, culture, everything. So, the intent is mainly because it is problematic for Russians to accept the world where this would exist. And so they say it doesn’t exist. And if it’s revendicating existence, we should destroy it. This is the level of understanding in Russia for tens of millions of people who are supporting Putin today. Since 2014, there have been territories occupied and taken, like Crimea and parts of Donbas. There’s been russification there since 2014 and since 2022 in newly occupied territories. It’s being reported and constantly followed what’s going on there, a forced russification in schools. Also, today, there is a lot of observation on the forcing of conscription of Ukrainians in the occupied territories into the Russian army to attack other Ukrainians. This is what’s going on in the occupied territories. This sometimes is mixed with the question of language. Everybody in Ukraine understands and partly uses Russian. Because of the russification story in the US, you were not forced by law to speak Russian, but if you wanted to go to university and acquire a diploma, you had to make it in Russian. So basically, to approach power in Ukraine, you had to learn Russian. This was the russification process for 50-60 years. As a result, Ukrainians generally use a mix of Russian and Ukrainian, which is the common language nearly everyone knows. This is also geographical. In the West, closer to Poland, it is mixed with Polish, more varied accents, and generally clearer Ukrainian.

Since 2022, it has become very clear that this is the language for which Russia tries to kill everybody. So, choosing to speak Ukrainian became an act of resistance. It is also the official language of the state, schools, and public life. Still, most people speak a mix of the two. Since 2022, many have been trying to learn Ukrainian intensively. On an everyday basis, I still hear Russian [spoken][, nobody really has a problem with it because everyone understands it. For younger people, it may take time to learn what feels like a new language because they haven’t used it before. The most common is still a mix of the two languages, especially in Kyiv, where you hear it daily.

Regarding culture, one interesting aspect is Russian propaganda. Inside Russia, there is a major focus on defining what Russian culture is. But if you talk to any historian, Russian culture is European. There is no unique specificity. It tries to sell the idea of uniqueness, but old books, paintings, clothing, and traditions — many of these come directly from Ukraine or from Europe because it was always linked. Of course, there is also influence from Asia in some parts of what is now called Russia. There is also the history of how what we know today as Russia was built. It is a history of colonization, starting from Moscow several hundred years ago, expanding to take the vast territory now seen on the map as Russia — so-called Russia.

In 2014, as I see what happened, a pro-Russian president [Yanukovych] lied to the public, claiming there would be talks with Europe. Ukrainians at the time were aware of what had happened, for example, in Georgia, where parts of the territory were also taken. So, the desire to move towards the European Union didn’t come out of nowhere. The EU was seen as not trying to seize your territory or annihilate you.

When President Yanukovych was kicked out because of the police violence during the protests — in Kyiv, it was more known, but Maidan was also known in Kharkiv or Odessa. It was a country-level movement. After he fled, the parliament had to vote him out and form a new government.

Then propaganda began, claiming this was a coup orchestrated by the US. So this was always how Russians wanted to see this happening because of the clear separation from Russia. From there, they launched an attack on everything, and the use of propaganda about the Nazis, for example, is something that I don’t think is really understood in the West. What is actually called when Putin uses the term Nazi, and what he tries to involve Russians into, understanding what he’s trying to say.

So it’s also about what was written everywhere in the history books after the Second World War, and how people in Russia see it that Russia fought the Nazi Germany and saved the world and Russia. But it generally never says that, firstly, there was a signed contract between the US and Hitler to actually take Poland and Ukraine [the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact – ed.]. Only later, they turned against each other, but they were first allies, and this part, for example, is forgotten. What is also erased is that it was Ukrainians in the Red Army who also fought. But they are erased because they were not any more Ukrainians; they were part of the US, and they were comrades. In history, they erased this part, and they took it as if it was Russian history. But actually, it was Ukrainians who marched to Berlin, a lot of them. And today, it is the same; when he uses the term Nazi, he doesn’t mean the few hundred who maybe do some politics or who have been attacking some people in the street. Putin doesn’t care because in the Russian army, there are open Nazis using Nazi symbols, and this is not a problem for him. The ideology itself is not a problem. The problem is the refusal to be part of the Russian world. And when he uses it, it’s his strongest tool to awaken in the older population all the propaganda from the US time that has been saying that it’s actually the Russian World thing to fight against Nazis and to erase all of what actually happened in this fight. But it’s not related to the real Nazi movement that could exist here. He really doesn’t care. If you look, for example, at Wagner [Group] founder [Dmitry Utkin] had SS sign on him, on pictures everywhere. It’s not something that is really a problem in Russia; they’ve been using, also, recruitment of the so-called Russian Nazis for some tasks.

The erasure then also comes to russification and the abduction of children, as you mentioned. The number that is given is 20,000 kids, but it’s hard to know exactly. It’s russification, propaganda on kids, transferring them. This has been done by a lot of far rights and a lot of fascist states. For example, Franco was taking the kids of all the past activists, of many who were born, to give them to families of his supporters. This happened in many places in the world. And this is also the case now because children are the future, in a sense. Also, Russia has a very low birth rate, so it’s also a very practical policy of having children integrated into society, which leads to a future. This is what they’re doing, and this is why it’s classified as a crime; there is an international court trying to accuse Putin and others of possible crimes until proven and get him arrested, which, for now, I don’t foresee in the near future. In occupied territories, there are other crimes. We have a comrade, Maxim Buchkevych, who used to organize no-border camps, he’s a human rights lawyer, and he was a prisoner for more than two years in a Russian prison in Luhansk. But because he joined the armed resistance in 2022, he and his unit were taken prisoners in June ‘22, and he was released in November 2024, if I’m not mistaken. He was also talking very frankly about how much he saw civilians, Ukrainians, who were in the same prison with him under charges of being part of the resistance as revendicating being Ukrainian; it could be very small things. Under occupation, you have repression from the Russian police and services in the whole of the occupied territories. And they’re also forced to learn Russian and not speak about anything else. And now you will be Russian. You will take a passport, and you have to gain some benefits. Some people are faced with very hard choices because a passport means a lot of things to you, including the ability to move in the future if you want to go to Europe if you want to come to Ukraine. Those things continue until today. Let’s see what will happen. There are more and more occupied territories.

The first “crime” is the destruction since 2022 of all the cities, of all that became occupied territory today. There was footage released by some Russian soldiers about Bakhmut not so long ago, about how it looks until today; it’s completely destroyed to the ground. Everything is destroyed, buildings and everything. It’s like a no-living zone. It’s total destruction and then occupied life, with people getting arrested for just saying something or showing something that would be seen as Ukrainian. So it’s a very obvious attempt at the annihilation of culture and the people directly, their bodies. What would peace mean? Sometimes, we hear these terms being used, and in occupied territories, what peace are you talking about? It’s not only territory. There are a lot of Ukrainians there who are living in terrible conditions. So, for me personally, when I hear about peace, of course, everybody here wants peace in the sense of not having bombs every day or drones coming into the city where you live. But really, there is no peace proposed in any shape with what Russia has become in Ukraine and in different places. I was talking with some Georgian comrades not so long ago, and everybody there fears that it would be escalation if the political resistance to Russia goes too far. And in some ways, it can be similar to what’s happening here, and we don’t know yet if there would be a Russian escalation there. For me, all this comes from the possibility of resistance that was shown by Ukrainians, which is dangerous for Russia. It’s dangerous because it’s giving the hope to many people that actually you can say no, you can face genocidal intent, and you can continue to fight and resist. This is very particular in the history of the post-US world. And this is the danger for Putin’s Russia.

TFSR: Since before the ramped-up invasion in 2022, at least since the war began in 2014, there’s been a lot of what we call Campism, the idea in the West of that anyone who is in opposition to NATO, to the US, to European powers, is a government that is good to live under, or that is somehow proposing ways of life that are positive for the people that live there, that are anti-imperial, that are anti-colonial. That’s a leftover of the Cold War mentality, and that’s been really present in the authoritarian left in the West. I can speak from the experience in the US, at least, that Stalinist, Trotskyist, Leninist, and Maoist organizations have been very much pulling from this logic. And the impact of the disinformation from the Russian state, who plays off of this through stations Russia Today (RT), they’ll show a lot of propaganda that is anti-Western, anti-US, anti-NATO, but in ways that are not critical and that aren’t reflective of the same criticism they would give towards what’s going on in Russian spheres of influence.

I wonder if you could talk a little bit about what role this perspective of Campism on the left in the West has had on the organizing that you all have been doing, and in how the war in Ukraine or even the Maidan, to go back a little bit earlier, are discussed. How can we do better in the West about embracing more nuanced explanations for how the real world works and building critical solidarities in complicated situations?

Anton: Here, it is usually called Soviet nostalgia, not Campism. But you can find some people who have been shaped in the US who would share this with some who on the left are called Campists. For me, it’s really related to political engagement and teachings that came in the time when there were the US and communist parties, and the links that can still exist with what remains of the Communist Party in Russia. And the analysis that people use is from before the ‘90s. It has been used as a propaganda tool to control people inside Russia and outside. I have been hearing about it being widespread among the authoritarian left everywhere, and some can be very active on social media or elsewhere. I remember how these same networks were also working against Syrians, for example, in the Syrian Revolution, saying that Assad was also part of the Axis of Resistance of old anti-NATO, anti-US politics. We’ve seen the effects of it in the sense of hundreds of thousands of people killed and nearly forgotten by a huge part of the Western left. And it’s still a huge problem politically to rebuild bonds after you take distance from reality, basically, and you try to say something that just shades everything, and then you can’t really come back from it. People we would call Campists, for me, are not people that will really be able to come around. And also, I sometimes doubt what the real links are with Russia, but this is for certain group I would really compare it to what happened with a very big ignorance from the left based on many texts that were written by those we call Campists in defense of Assad. And today, with the fall of Assad, I think there is a big need to rebuild links between the Western left and the population in Syria. And we’ve been facing a bit of the same.

The thing is that it is used by the Russian propaganda a lot. They try to send it to the left or to the right, depending on what they understand as left or right. Is Communism left or right? For me, it’s rather economy-related. But it’s very easy for them to reuse themes that were used under the US and try to make them fit today. And there is an audience that is ready to share it and to think that this is what’s going on with NATO and its relation to the world, or what’s happening in Ukraine? When you start to hear Trump making announcements that he would attack another NATO country, I don’t know how some Campists are now dealing with it, but at some point, they will start to support Trump. At some point, you really need to understand what is the politics that someone is calling for. Regarding us, it was some people who were calling for forgetting the reality of what’s happening with Ukrainians, only talking outside of it, focusing on main empires, like the USA and Russia, and forgetting the victim. The whole geopolitical situation is seen as the Cold War: we are still in it, and there is an Axis of Resistance there. We need to maintain this because we don’t want to have one big empire taking everything. I think this is the logic, but how it’s used is actually to make people disappear, destroy cities, and kill a lot of people, either under repression, like in the case of Assad, or under bombs, like in Ukraine. And in other places, it works the same. So, for me, we didn’t call it authoritarian left. And in the anarchist movement, we’ve been fighting with them for a long time, and this is just one other reason for it. And I think on the left, there needs to be a lot of acknowledging of what’s happening with this, and we need to fight it because it’s really coming in the way of the solidarity between the people in struggle, which I think is one of the basis of leftism. So for the left, I would say, you have to deal with the problem of Campists (that again we would call Soviet Nostalgicism) in the sense of influencing analysis with sometimes a lot of texts, very long texts that I’m not sure anybody even read until the end.

TFSR: How have you and the resistance to the invasion been impacted by the change in administrations in the US? Does it seem like other European nations will support defense against Russia, and what prices might they demand beyond the holding of the line to slow or stop Russian expansion? And I ask that last part because the US under the Trump administration has been making demands on the Ukrainian state for easy access or free access to rare earth minerals in Ukraine, like holding Ukraine hostage to be able to extract so that Ukrainians have to make the decision of do we get invaded from this side, or do we maybe be able to defend and prolong the resistance maybe with weapons from the US in exchange for giving up territorial integrity and autonomy.

Anton: This particular deal, for me, is very interesting. A lot of these so-called rare earth or other minerals that you can find in Ukraine are actually either under the front line or in occupied territory. And so sometimes it’s a bit hard to understand what’s the goal of it. Does it involve deoccupying territories so that it could be used by the US, possibly in this case, or is only about the part of minerals that is located in territory that is not occupied. When I try to follow what is being said, it either seems like there is real ignorance and just a way to make easy money by the Trump administration of what’s actually going on in Ukraine. Or it’s just a media game to try to gain some attention, and then, at the end, do something else behind the curtains. So everybody talks about this in the US, but in the end, we can deport whoever we want and start to destroy the state as it is, all the social security and everything. And maybe they will not realize it because everybody is talking about rare earth materials.

For me, sometimes it seems like this because Ukrainians, by the decision of the current president, so far have been refusing it because it doesn’t make any sense, but are trying to play the media game not to frustrate this media attention that Trump is trying to have, and trying to navigate it. But for me, the ceasefire talks that we have today, for example, are not bringing anything into practice – we continue to have drones, and there are attacks on the whole front. Nothing changed in the occupied territories. So, the war is the same as it was before talking about it. Russia goes in a complete refusal and says, “We want the capitulation of Ukraine for making a ceasefire.” It’s completely unrealistic. This is the media part, and I’m a bit wary of why it is used by the Trump administration because I think this deal is bullshit on the table; there’s nothing real about it, also because it’s such a blunt theft, meaning it will represent four times more than what was actually given as aid – completely unrealistic things to have in any contract.

As for the capacity: in a sense, today, the situation is better than in 2022, of course, because 2022 was the possibility of full occupation or destruction of the place and now, there are means to resist. There are three times more people in the Armed Forces than there were before. And there’s been construction of autonomous arm production also in Ukraine with the financial aid that came in the last years. And we’ve also been seeing Europe boosting its own production. It looks like everybody is actually listening to Eastern Europeans saying, “No, it will not stop there.” You can see Poland is more than doubling its amount of soldiers. And so there is a good understanding that this is not going to be settled by any ceasefire unless there are actually what people call security guarantees. We have to understand that it means arms and soldiers to be there, to back it. This is what I have seen built since 2022. In the beginning, Europe was really like hands in the air, with no response, completely frozen by shock. And it took three, four months, I think, for Europe to start to react a bit. So these are the general lines, at least in my understanding. The situation is much better, and there is a good possibility of resisting today in Ukraine. It will need support and guarantees, and I feel like it is being built in Europe. Of course, we can say it’s not something that anybody wants, but it’s something that is really clearly created by Putin’s Russia. People have to understand that for the last 20 years, he was actually helping in Syria. He was making wars inside or outside Russia, with Chechnya, Georgia. He’s on a war path, and he sees this as the path to keep his power and leave his trace in history. And his trace in history is more war.

For us as a collective and as a movement, including internationally, it brought a good new understanding of what Campism is, what the left is, and what is the authoritarian movement doing in this situation. Again, I will just emphasize that since 2022, we’ve been seeing actually a lot of support, really a lot. I think nowadays, we are at about half a million euros that has been donated so that we can work in total, and every month, we continue to see the need for the support that we organize, and we can create more.