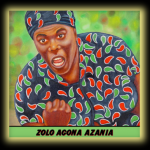

Zolo Agona Azania

This week on The Final Straw radio we are sharing a chat that Bursts had with New Afrikan, former Black Panther and political prisoner, Zolo Agona Azania. Zolo is from Gary, Indiana where he lives now, working a job and also doing re-entry work with the formerly incarcerated and community service to break cycles of trauma. After 7 and a half years in prison from ages 18-25 where Zolo engaged in political education with members of the Black Panther Party from Indianapolis, he was released. In 1981 he was re-arrested, picked up by the Gary police while walking around the city after a bank robbery took place, resulting in the death of a Gary police lieutenant. Because of his political views and circumstantially being on the street at that time, Zolo was convicted by an all white jury and sentenced to death.

Zolo beat that death penalty from within prison twice and blocked a third attempt by the state to impose it. For the hour, Zolo talks about his life, his parents, his art, his education, his time behind bars, his political development, the Republic of New Africa, and his legal struggle.

To get in touch with Zolo you can email him at azaniazolo5( at)gmail(dot )com or you can write

Jumpstart Paralegal and Publishing

PO Box 64854

Gary, Indiana 46401

To see more of Zolo’s art you can visit this support page!

. … . ..

. … . ..

Transcription

TFSR: We’re sharing a chat that I had with Zolo Agona Azania. Zolo is from Gary, Indiana, where he lives now working a job and also doing reentry work with the formerly incarcerated and community service to break cycles of trauma. After seven and a half years in prison, from 18 to 25 where Zolo engaged in political education with members of the Black Panther Party from Indianapolis, he was released. In 1981 he was arrested, he was rearrested picked up by the Gary police while walking around the city after a bank robbery took place resulting in the death of a Gary police lieutenant. Because of his political views and circumstantially being on the streets. At that time, Zola was convicted by an all white jury and sentenced to death. Zolo beat that death penalty from within prison twice and blocked a third attempt by the State to impose it. For the hour Zolo talks about his life, his parents, his art, his education and time behind bars, his political development, the Republic of New Afrika and his legal struggle. To get in touch with Zolo you can email him at azaniazolo5@gmail.com or

Jumpstart Paralegal and Publishing

PO Box 64854

Gary, Indiana 46401

TFSR: Would you please introduce yourself for the listeners?

Zolo: My name is Zolo Agona Azania. I am from Gary Indiana. I just was released from prison upon parole on April to six 2017 at the spending over 35 and a half years in prison.

TFSR: And what was your childhood like?

Zolo: My childhood was pretty much happy. I was born on a farm in a small town called New Magic, Missouri, on the Mississippi River. The town had a section called LaFord. And that’s where the farm was. My parents moved to Gary, Indiana when I was a little over two years old. And there I was raised and where I went to school

TFSR: Before you had said that, your parents moving you up there was a part of the mass migration. What were they might migrating from or migrating towards?

Zolo: Well, we lived in a poor rural area. It was in Missouri Valley where there was a lot of flooding. The levee was like our backyard. I liked it, but you disrupt the school. So there was many days during every year that school were disrupted because of the floods. My mother, she was an athlete when she went to school. And she told told us, the children, that she used to want to go to school so bad that her father used to set her on the side of the axle on the tractor and drive through the mud and water so she can get to dry land and get to school. So I said “that’s what I want to do! I want to go to schools!” “Oh, no, no, you got you can’t go.” So I really feel bad about that for a long time. So I just didn’t have any control over this. I just ran the streets and did what I wanted to do as a child growing up in the city. I became a country boy in the city. So I used to bring all kinds of stray animals home: lizards, snakes, frogs, stray dogs, every dog you can think of… cats! I really didn’t have any fear of dogs. And the first time I get in trouble was stealing two Doberman pincher puppies who had just freshly had their ears and tail clips.

TFSR: Did your parents let you keep the animals? Or was it just like “no no no bring them back!”

Zolo: Sometimes, sometimes. My mother was pretty much against it. She didn’t like female dogs, because they will have puppies. And she want puppies all over the place. So always had a female dog. I never hardly had a male. Always was a girl. But when my parents weren’t looking, I was sneaking dogs in the house. Or I would feed them by going into refrigerator and getting some hot dogs or something leftover. I would put in my pocket or somewhere and sneak it outside and feed it to animals.

TFSR: How far did you go in school? And what did you enjoy studying?

Zolo: I started out loving school completely. But I kept running into different roadblocks. I wouldn’t have been able to figure it out then. And by the fourth grade I wasn’t doing too well. I lost all interest in school. But my primary interest at the time was math, English, and art. I excelled in those things all through school, except for the other subjects. They went down. My English stayed up kind of high. My art stayed up high. But all the other subjects, they went down. I just didn’t do the work.

At a certain time, I was in… around about the fourth or fifth grade, someone came up with a new system of doing math. A new way of doing math. Matter of fact, the symbols had been changed. And they still use the symbols! The period for multiplication, the dot for decimals. The line with the dot over and above the line like a colon almost. But you had the division. Instead of writing the numbers on the top, you would draw a line and then do all the figuring on the side. So I had begin to learn that and I was getting pretty good at it. All of a sudden teacher came in one day and say “oh we don’t do that no more.” And I just like threw my hands up in the air and I just… I’m not trying. I’m not doing this no more. Math never recovered.

TFSR: Is that when they started doing long division?

Zolo: It was long division. And I’d liked it because I learned how to do it and just all of sudden just stopped. Saying “we don’t do that anymore, we going back to the old way.” I never recovered.

TFSR: I guess jumping forward a little bit. How did you find yourself incarcerated in the first place? Like how did you find yourself in prison?

Zolo: My father passed away when I was nine years old. I was real close to my father. He’s also a Korean War Veteran. Even though we were living in a city. My parents took me from rural Missouri. My father took me fishing with him all the time. So I was around water. I was in the woods. And we would sit there on the banks of the pond or river or the lake. And he would tell me to be quiet. He said fish can hear us. And if a bird flew by or some animal, he would like touch me or do his hand where he can catch my attention. Then he would just like point. My first time seeing a pelican in a wild, flying low over the water looking for a fish to scoop up. Wow!

It was fascinating to me, you know? And then he would tell me about the fish. Fish can think and they are smart. Sometimes the fish would learn how to nibble the bait off the hook without getting caught. And sometimes the fish would come up to the bank, past the lines we got in the water, and they would come up and look at us. He said “Well, let’s go. We are never catch anything today.” So I learned a lot from my father out there in the woods. So when my father passed away I didn’t have anybody to fill that void. So I would go on my own. And is my mother found out about it she would beat me to death because she was afraid that I would drown, because my grandfather drowned. My father’s father drowned fishing with another buddy. They were drinking and got drunk. Got to arguing. Somebody stood up in the boat. The boat flipped over. My grandfather could swim but he got trapped under the boat and couldn’t get out. Drowned.

So I ended up running the streets. I used to build go-karts. I used to do the things that person would do when he was in the woods. I had me a little hatchet. I used to go find somebody’s tree, little tree. I would chop it down and run. I stole… well I really didn’t.. I did steal them, but I was put up to do it by an older boy who I looked up to. I was about 12 years old. He was 14. And we he knew where some dogs were in the garage. And him and another boy came to me and said they wanted me to help them because they were too big. They couldn’t fit through the window. So they picked me up and put me through the window, say “wow! You can get through this window.” “No I can’t. Can’t nobody pick me up.” So it’s always an excuse. Chicken! So they kept calling me chicken. And so that was like peer pressure. So I bowed to the peer pressure. I climbed through the window, and I went and opened the doors. So now they’re telling me to go back in there and bring the dogs out. I said “Well I got the door open.” We were on some bikes. So I wouldn’t get the dogs out. And I was holding the two puppies while Jacobi was pedaling the bike, we rode away. Got away.

Well, we eventually got caught. So because of my age, and I had never been trouble before. Well, I never got caught… put like that. I didn’t have a record. The judge did not want to send me away, because they may have led me on the wrong path and it can be the beginning of a long cycle. So he put me on probation until I was 18. But I did not know I was on probation until I was 18. Well, I successfully completed probation. They kept giving me one chance after another. So by the time I did turn 18 I caught a felony case. It was a home invasion case. And I was sent to prison the first time on that charge in 1974. I was arrested in December 1972. I stayed in the county jail for 16 months, eventually pled guilty on that charge and that’s how went to prison the first time.

TFSR: So you were in for 16 months before you actually pled guilty. That was all like pre-trial.

Zolo: Yes that was all pre-trial stuff. You know, waiting to go a trial. I originally was going to have a jury trial. But my lawyer and my mother talked me in to pleading guilty.

TFSR: Was that a public defender?

Zolo: No I had a paid attorney. I had a private private counsel.

TFSR: They just figured that in front of a trial, a jury, you would get a harsher sentence?

Zolo: Yes. I was facing a life sentence.

TFSR: Wow.

Sorry to jump back and forth, but what sort of work was your mom doing during that time?

Zolo: Well, Mom did odd job that she could find. When my father passed away he had military benefits. He also had Social Security. My father also had several insurance policies. He would talk to me about them. He would be at the table. He always was reading and writing. So I wanted to read and write too. So I kept saying “I want to write!” But he would tell me “Go on, boy!”. But eventually, he came to me one day said “Come on, you gonna learn how to read and write.” So he started teaching me how to read and write at home. And when I didn’t follow instructions, or was slow picking up on it. He hit that belt. Right across my back. Oh!!! He said “That’s the answer! You didn’t answer the first time. You know what it is. What is this answer?” “That’s an A. “And what is this?” “That’s a B.” “And what is this?” “That’s a C.” And I had to keep going, and then he took the paper away. And they made me say them without looking at the paper. And here come that belt. WHAP! I ended up learning how to read and write.

I was doing pretty good at home. I was always told I was smart. And when I started school, I was one of the students who already knew how to write. I knew how to write my name. I knew how to count to ten in kindergarten. By the time I was in the first grade I knew how to count to 100. I was the first student in my class to count to 100. I knew how to tell time. This means a minute, this is five minutes. And it’s divided in five minutes around the clock. Every every five minutes there’s another five minutes added. So that’s how you tell time. Well, so I did that while I was in the kindergarten. We had a little mechanical clock, like where you can see the gears turning. And the teacher might say, “put one o’clock.” I put the hand on one o’clock. “Good!” You know, some students, they just couldn’t get it. So I thought that I was a little better than others because I knew something that they didn’t know.

Well, my father passed away. All that stopped. Because I didn’t have anyone at home to help with homework. I didn’t have anyone at home to teach me anything or help me with my school. My mother didn’t do it. She said that she did not know about this new math and she didn’t know a lot how they were doing things at the time. This was in the 60s. So I was just on my own. And my mother did not show the interest in school that I expected her. Even though I still held on to my art, my mother would discourage me from drawing. She said “you always want to focus on your art, on that art, on that art. You just keep harping on that art and your grades is going down. It’s more to school than art.” So I resented that. So I just stopped drawing from for a long time.

Till one day, I was looking at a magazine and it had a picture with Abraham Lincoln. And if you draw this picture you can win a prize. So I drew the picture and sent it in. I won the prize! But the prize was to go to art school. To take the art correspondence course. Matter of fact, from the Art Institute of Chicago. And the art Institute of Chicago sent a representative to my house after I had won and found that I was too young you had to be at least 14 and I was 12 or 13. I was somewhere around there. But I wasn’t old enough. They said well since you did such a good job. And I showed the representative the other drawings that I had in the house. They said they going to give me a waiver. They said that I was good enough to do it. So they let me start taking a correspondence course. We put the papers out and my mother started paying for it. But I ended up running the streets now. On my own I’m losing interest in art. So I start running the streets. I ended up going to prison. So while I was in prison, I said “I’m just gonna finish my art course.” So I wrote a letter to my mother and told her to send my drawing board and my pencils and the equipment that was given to us from the school.

TFSR: And she sent it to me. I wrote a letter to the to the school and said that I would like to finish my course. They said that I owed them 200 and something dollars. I did not know that my mother has stopped paying the tuition. Well, I was convicted 1974. But I was arrested at 72. December 1972 to April 1974. And then I was sent to prison. They counted my jail time in county jail towards my sentences. So, while I was there I met a man we call Rooster. He was a Picasso to the penitentiary. Picasso was a famous Spanish artist.

Zolo: He did his rendition of the Mona Lisa. He did what you call abstract and surreal art. And so I began to do surreal art. Surreal art would be like, if you would draw a forest, and the forest is there, but in the middle of that forest is a giant owl. But the owl is like it’s superimposed on the forest. Then it may be a clock where the owl is looking at a clock. And that would be surreal. Most of my art, if you look at my art… it’s done that way.

TFSR: Yeah, I’ve heard it described that surreal art is a lot of reaching into into your dreams, sort of, and looking for imagery there and then bringing that out, just sort of trying to help people make that connection between what their brain… not their logical rational, awake brain tells them but what their inside mind and body tell them and make that connection.

Zolo: Yes. Yes. That too! Salvador Dali did a lot of painting like that. I think he did the one with the clock. The clock looked like it was melting. That’s surreal.

TFSR: And you were able to get that equipment sent in and work on it in?

Zolo: Yes. So I really honed my skills while I was in prison. But during that same period of time, I had begin to do systematic political study. Reading and study of what was taking place on the streets. And people that was being arrested and coming into prison who was politically active on the streets. That’s what that was like beginning to be the majority of the population. Who had influenced in the population? These prisoners. So I gravitated towards people like that. And that that is how I began to get be re-educated.

TFSR: Last night you shared a little bit about that process of how you got involved with people that were doing this thinking and this talking and they held like an air of respectability. Even even the staff recognized it. Can you talk about those people and how that brought you into the study group that you’re in?

Zolo: Yes. Children are psychologically… physically and psychologically insecure. So children form groups as protection. They play together in small and large groups. I was a young man, I was a teenager, I was 19 years old when I came in the prison door. So I gravitated towards other young people like myself. And we ran together. And we protected one another. But I used to see certain prisoners walk by themselves, they didn’t run in a crowd, but they still had protection and respect that I was striving to get or earn for myself. And the rest of people in my group, the same thing. So I said, that’s how I want to be. Well, I eventually was able to get to know some of those people. And they spent time with me just like William Turner, we call him Rooster, who taught me how to paint and the concepts that he painted. Hugh Lions, we call him Mwatha ▪. He was an expert dialectician. So he taught me about dialectics and the study of the contradictions inherent in things. Makau ▪ he was a martial artist and he exercise all the time. So I learned some self defense techniques from him. I also learned about George Jackson because he was trying to imitate and practice some of the things that George Jackson wrote about in his book. And that was the beginnings of my reeducation and driving the role of political consciousness.

(▪: Mwatha and Makau’s names are informed guesses at a correct spelling. If we find we’ve spelled these elders names wrong, we will correct this -Editor)

TFSR: Was it difficult to get the materials to study in the study group? and who all was participating in it? Like what kind of prisoners?

Zolo: Oh, yes. At that time it was hard getting that material into the prison. Because the prison saw it as a threat to security. They always say it was a threat to security. But even still, during that period of time, them books seemed to find their way in prison. And it was now allowed in. But you have people in prison who had a thirst for knowledge, who had a thirst for reading and learning, unlike what it is today. Well, it’s still around today, but not as it was then. Everyone wanted to know something. Everyone wants to learn about something. And during that time, throughout the whole country, because I read an article in Ebony magazine where different prisons would highlight where they have Black culture programs. We even has a Black study class that we had attended. And it grew. A Black study class was a non accredited class. You weren’t forced to go to it, but you volunteer, but you couldn’t get any credit for it. For attending the class. We were not interested in that. We was interested in being able to study and learn. And a lot of prisoners had that type of attitude. It was expected when you come to prison. One of the slang terms we used to use was “carry you sponge with you.” Because sponges absorbed water. So we want to absorb the knowledge that was in the book. Yeah, a sponge.

TFSR: Those two older gentlemen that you mentioned who were running the study group were members of the Black Panther Party.

Zolo: Yes. They were members of the Indianapolis chapter. Indianapolis had a pretty good, well organized chapter. Some chapters was not as well organized, some were corrupt – and basically was counter revolutionary. You know, they were just Panthers in name only. But Indianapolis was actually practicing the 10 Point program expound. On the leadership of Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale. And COINTELPRO played a part in its destruction also. But in the process, the people that was sent to prison who was members of the Black Panther Party, they kept it going while they was in prison. So I became one of their students. And in some kind of way it came out that I was a member of the Black Panther Party. And I saw it on the internet myself. And some people had mentioned it to somebody else, and it got back to me. I’m like “No, I was never a member of the Black Panther Party.” I was a student of members of the Black Panther Party.

TFSR: Would you have been a member? Would you have joined?

Zolo: I would have been probably, I probably would have been. If the party had kept going I probably would have been, yes.

TFSR: Okay, so you’re arrested 1972… 16 months. By 1974 you are imprisoned. When did you get out?

Zolo: I got out July 8 1980.

TFSR: And can you say anything about your political involvement after that point?

Zolo: Well, after I was released from prison in 1980, I did seven and a half years. I immediately sought to put into practice the things I’ve learned. The new things I’ve learned while I was in prison to make a difference within the community. But I was not interested in walking on anybody’s picket line. I was not interested in anything non violent if violence is being practiced against me. Now, if it was no violence practice against me, then I practice no violence against anyone else. I was peaceful with those who were peaceful with me. But I did not turn the other cheek for anybody who tried to put their hands on me.

TFSR: Those those words seemed to me to reflect Malcolm X’s sentiments.

Zolo: Yes, that includes the police and anybody else.

TFSR: You were incarcerated again after that. What were the circumstances around your rearrest and what was your sentence?

Zolo: Well, I was accused of bank robbery and murder of a Gary Lieutenant police officer. And I was facing the death penalty. I was never identified in the case. No one ever said. “That’s the man right there. That’s him.” That was never done. It was circumstantial evidence about the color clothes I was wearing. Where I allegedly ran. Where I allegedly tried to hide certain things in bushes. Running through people’s yards and stuff like that. So even though even though the police officer wasn’t sure. I was the only person on the streets at that time. No one else was standing around. So the police obviously grabbed me and threw me in the backseat of a car, handcuffed me, and took me down to the police station. So they never arrested anyone. Well they had arrested some other people. But it was after that I was in jail.

TFSR: Did the police or the court accused you of being affiliated with any organization?

Zolo: Well, at that time, they did not know who I was. They just thought was just some random person who was accused of a crime. But after they found out who I was. That’s when the sensationalization began to be published in a newspaper. Printed on the newspaper. Because I openly declared my citizenship as a conscious citizen of the Republican New Afrika. And they consider the Republican New Afrika a terrorist fringe group, as they called it. So for that reason, I was singled out and made to be the leader of this bank robbery and murder of a police officer.

TFSR: Can we talk for a minute about the Republic of New Afrika? Because I’m very basically familiar having read some articles online with the concept. And I’ve read that the Cooperation Jackson, for instance, down in Mississippi was a project that had its roots in centuries of resistance to oppression of Black folks, but in particular, folks who identified with the Republic of New Afrika attempting to create an actual physical land that could be incorporated into that wider project. Can you say for listeners, where that idea came from? What it constituted and what sort of folks who are engaged in the project of New Afrika?

Zolo: Yes, absolutely. That that was not a new concept. It was something that as a consequence of the slave war, and the slave trade of African people brought to this country. Most were concentrated in the southeast United States. And in some of those areas, the captive slaves were a majority in those places. There were all Black counties, they were all Black areas. In the 1930s, and 40s, the Communist Party USA financed a study. So a man named Harry Hayward who was a member of the Industrial Workers of the World as well as of the Communist Party USA, and a veteran of the Spanish Civil War. He was a member of the Abraham Lincoln brigade, where Harry Haywood went to the South, the southeast, and he did a systematic study and wrote about the Black Belt. It was called the Black belt, and how the people in those areas who were members of different tribes, originally fused together as one people.

TFSR: Do you mean like folks who came from ancestors of different parts of Africa who were stolen here? Or do you mean indigenous tribes that were living in that area?

Zolo: Well, both. Well, first, for example, you had the Igbo people. You had the Fulani people. These are different tribes. You had the Mandingo people, you had the Zulus, you had the Makoshas, you had the Ankahs. You had different types of different tribes. And even though the indigenous people were there also, over a period of time, there was a fusion and an intermingling, as well as an interbreeding. And those people became one people. Some of the slaves even join different indigenous tribes, and they were accepted as members of the tribe. And so these people became known as New Afrikans. New in the sense that we haven’t uprooted from a country and brought to another but we did not change who we were. We were still African people who was living in another country and we brought our culture and some of our words with us. And those words, some still survived to this day. Such as the word banana – that comes from the Wolof people. You see what else? Goober for peanuts. So there’s a lot of words that’s in the English lexicon now that comes from African words.

TFSR: And that was brought over by the populations that were disinterred from Africa, not just through European interrelation with North African and with the astronomers and mathematicians and scientists that were in Africa, but specifically brought over by the transatlantic slave trade.

Zolo: Yes. Now, even though what you just got to saying, that took place also. It was not as widespread as what the effect of the Atlantic slave trade had on the indigenous population, as well as people of African ancestry, African descent, who were uprooted from their country. Primarily on the west and southwest coast of Africa and were brought here to the United States, what became later known as the United States.

TFSR: So among the people that use the term New Afrikan, because I’m sure there are a lot of people that don’t, who are of African descent, is that project, that nation, or… well not that nation because a nation doesn’t need a State attached to it, or a border necessarily. A nation as a constituent of the people that are engaged in it. But that term, that phrase, that identity continues to be used is an amalgamated landmass that is self determining, still a project of people that are identifying as New Afrikan?

Zolo: Yes. There are villages there right to this day. For example, the Georgia and Carolina Islands. Where you have people who held on to many of their ancestral ways. They were called the Gullahs. They are trying, when I say they I’m talking about the State and federal government are trying to uproot those people and to take that land and turn it into vacation resorts and golf courses. So they’re still just trying to destroy a people’s culture. The country is the land. and the nation are the people. And we have a historical relationship to that land in the southeast United States that we called the Republican New Afrika

TFSR: I have read about the Ogeechee folks in South Georgia also who during slave times were were farming rice, out in the in the wetlands and whatever. But after the war, gained some autonomy before the federal government stepped back in and took the land and gave it back to the white landowners. So once law enforcement and your prosecutors found out your political affiliations and your ideas, I had heard you mentioned before that your face was plastered on the newspapers for five years.

Zolo: Yeah, for five years straight I was in a Gary Post Tribune everyday. Something was said about me every day. Eventually it started to fade a little. I would be in the paper – the court made a ruling on my case or if I filed some type of petition, they would say “He just filed a petition! He’s claiming this and claiming that.” Or my appeal would get denied… “Oh, appeal denied! Execution date will be set.” So it went on and on and on and on like that for the rest of the years I was in prison.

TFSR: So you were put onto death row. How long did you serve that and what sort of self defense were you able to muster during that time, like a legal self defense?

Zolo: I was on death row for a total of 27 years and three months. At that time, I did not have the right legal representation. The attorneys that I had were court appointed lawyers who did what they were told to do, and nothing more. And so they did not serve my interests of how I wanted to fight my case, or prove my defense. It wasn’t until Michael Dortch and Erica Thompson and John Stainthorp of the People’s Law Office. When they came and began to represent that my case received the attention that it deserved. And they brought up the political aspects of my case and show how was singled out because of my political beliefs and my political activities.

TFSR: So until that point, you didn’t have a support committee or anything like that on the outside or anyone agitating?

Zolo: No, no, I had no one. My mother, some members of my family, a few friends. I had support from prisoners. But we was prisoners can only do so much to help each other in that respect. But that was it.

TFSR: And the way that you’ve talked and not because I’ve read up on this, but it sounds like you’ve educated yourself very deeply in and the legal processes and in your own self defense, despite having lawyers that ended up joining your side. Would you have considered yourself a jailhouse lawyer? And what was that process like?

Zolo: Yeah, eventually happened. People have been recognizing my efforts, and I actually became a jailhouse lawyer. I didn’t plan it that way. I did what I thought was best for myself, because there was no one else to do it for me. And I was angry in that process, because I did not have the help. So I saw help from other people. So one day I got a letter from a man who was a quadriplegic. But he owned a nudist camp in Roseland, Indiana. His name was Richard Drost. I don’t recall his first name right now. He wrote me a long letter back and he couldn’t write with his hands, he had this machine that he talked into and it wrote a letter for him. So he sent me a long letter. In that letter, I’m reading waiting for him to say “I’ll help you.” I’m waiting for him to say that. But he just kept saying, in general to make it short, he said that the prosecutor got many cases. Yours is just one of them. But you only got one case, and you got 24 hours in a day to study. You have more time to work on your case than the prosecutor got to work against you. And he said “use your knowledge, learn the law, and fight and fight for your rights.”

I was so pissed off. I didn’t tear the letter up, I just folded it and threw it to the side. But I eventually was thinking. I said “Wow, he got a point there.” So I tried to read and study and learn something about the law. I just read anything. Give me a law book, regards what it is, I’m just reading it. I read aimlessly. Book. Law. Read it. Then I began to understand the concepts of the statutes and how they applied and the language that was used to explain these things about the law. I began to put certain things, books to the side, and now I’m looking for particular things about the law that concerned my case. And from there, I just learned about it.

TFSR: So you said it was 27 years that you were incarcerated in that stent. And so how were you able to get yourself off of death row? How were you able to overturn the conviction that would have sent you to, I assume, the electric chair?

Zolo: Well, I was given the death penalty twice. But I never stopped fighting. I did not fear speaking truth to power. I did not fear that it was going to kill me if I speak my mind. I did not fear that. For some reason or another, they conveyed that message to me that they feared people would listen to me. So I saw that as an opportunity for myself to organize, to use my case to organize. To use my case as an example of injustice. So I went back and forth from public presentation of my case, to the courtroom presentation of my case, even though the court was supposed to be public. It’s not really presented in such a way for the public to understand what’s going on.

So my theory and practice was to use the courtroom as a classroom, and to instruct people, not necessarily the judge or the prosecutor or the public defender system, but to instruct the people who were in the audience who was listening. Even though I had my back to them, and they was in the audience observing the trial, I spoke loud enough. And I explained things in common layman terms with every day common person would understand what I was saying. And I call it using the Dick Jane and Sally words. You know but of course they don’t like that. They like for you to use large words. They say “keep it simple.” That’s not what they actually mean. They say keep it simple? That means don’t overdo it. Not keep it simple, per se, or in actuality, not keep it simple. They want to keep it simple, then don’t use the Latin term. Don’t use then Greek terms or the or the language that the ancient Romans spoke. When they use words like that, they are trying to deceive the public.

Latin is dead language and they keep it alive through the legal court system. So I learned Latin. So when they was in there talking they will say things that I didn’t know what they were talking about it, but they were talking about me. What did he say? What does that mean? “Okay, your Honor. Okay. All right. That’s it. All right. Court Adjourned.” What happened?! I’m sitting, my heart beating fast. I didn’t know whats about to go on.. So I learned what the words meant. So when I learned what those words meant, I began to use them. And when I would be in trial and I’d get the opportunity to speak without the threat of the Bailiffs putting their hand on their pistol like they ready to shoot me and being gunned down in the courtroom, I would explain what that word means. Instead of using the actual word I would use the meaning. For example: Nunc Pro Tunc. Nunc Pro Tunc means that something was done that was a mistake, that was not a fatal mistake where you couldn’t come back and correct it, that the judge made. So, if I’m having a Nunc Pro Tunc hearing and I’m trying to get something in the record concerning my defense that’s in my favor. I may use the word Nunc Pro Tunc but then after that I’m only using the definition. The judge made this mistake. The judge done this! The judge done that. The judge left this out. This mistake here was prejudicial to my defense. That’s when the judge did this. The judge…. that’s enough of that! But if I keep saying the word Nunc Pro Tunc then the audience wouldn’t know what I was talking about.

TFSR: When we first met, like in the library, and you were talking about studying these older cases and learning from them, you made a point of saying that learning the rules of how the court operates, but not basing your defense on those rules, necessarily. This seems like an example of that. Just sort of seeing how they operate and going your own way with an understanding of that, seems like a really smart approach, but also something that a lot of people would be hampered by. They would see the rules and they would say “I got to color within these lines” as opposed to “I see what those rules are. I see what they expect. I have my own ideal of what I want to achieve out of this.”

Zolo: Yes. Correct. That’s accurate. It’s like playing pool. You know, a person can play pool, but they may do particular pool shot, and somebody may call it a trick shot. Well, in a sense it is a trick shot. But it has to do with skills, you are playing within a certain rules. But there’s no rule that says that the ball just can’t bounce up in the air, jump over another ball and hit another ball and the ball going to pocket. They didn’t figure that one out that a ball cannot come off the table, it cannot go over another ball and it can’t come down and hit another ball to knock it in a pocket. They didn’t say that. So person do a shot, or trick shot as they call it, and make his point and knock the ball in the pocket, corner pocket, side pocket or whatever. It’s all within the rules.

TFSR: It kind of reminds me of those stories of like, the devil comes down and somebody has an interaction with them. The devil challenges them to something and the way that they’re able to get around it. The danger is the devil is in the detail, right? Of what is said and what isn’t said contractually. But you are literally dealing with the devil when you’re going through this court circumstance. And so paying attention to the details and just saying, “Well, you didn’t you never said I couldn’t do that. And that’s not in the rules and say that I can’t do that. You never said that I couldn’t explain actually what the words mean to the jury and break it down for the people that are in the audience or talk loud enough so that they can understand what I’m saying as long as I’m not disrupting the court.” I think that’s super smart.

Zolo: That’s what I did.

TFSR: So you had that overturned. Or both of those overturned, you said, and those were consecutive?

Zolo: Yes. I got my death sentence overturned in 1993. That was the first time. But I have been fighting my case for like 12 or 13 years. And I basically the jury recommended the death penalty for the second time. So I get the death penalty in 1996 for the second time. I found my appeals. My appeals were denied, I went to the US Supreme Court. So I filed a successive petition, which is a special petition. You have to get permission to file one of them. Because effectively, my State appeals ran now. It was within the rules I can file another petition if I can show that an egregious violation of my due process rights has occurred, or been committed by the State or the court. So I filed one of those petitions because I had an all white jury. It came out later that the jury had been rigged against me. There were jury members, as well as some members of the court system itself, like the Jury Commissioner. And this came out through an investigative a reporter at one of the local newspapers had done. So I took the newspaper article, and I filed the petition and said “this is what happened to me within this period of time.”

So it took place between January or February of 1996 up to September 1996. It was taking place within there. So that’s when my trial was held. Within that particular frame when the jury was selected. Come to find out, I was one of those people that had a tainted that jury because of that reason. So now we have to go through what you call legal wrangling. I have to show that I was prejudiced, and my due process rights was violated as a member of a class. So that is how I was able to argue that I am a distinct member of particular class. And I use those same examples of the Black belt South. People uprooted from Africa during the Atlantic slave trade, supplanted over here, they came with their ways, and culture, in their heads and in their daily practices. And they applied them while they were here that did not change who they were. They were African people then, and African people now coming into a new awakening of themselves. At times we saw ourselves as different individual tribes and those tribal distinctions and conflicts have been blurred and diffused and we have become one people. Instead of one individual tribe, we are saying we are one New Afrikan nation. And this is what I did with my class argument, that I was singled out and prejudiced as a member of particular class, that New Afrikan class.

TFSR: So the court granted relief?

Zolo: Yes, they granted relief and overturned my death sentence for the second time. And the judge threw the whole case out. I got special judge, he threw the whole case out. This this judge was a judge advocate or jag as they call it. He was a colonel in the Army Reserve. And Steve David was a civic judge. He encouraged young people, he would have field trips to court and he would teach young children about their civic duty and how the court system worked. And so we had a fast and speedy trial argument. It took three years for them to try me. And I had been fighting the case for that period of time. So we found a petition to dismiss the case for violation of my rights because witnesses died, evidence that I needed to prove my issues was gone. I couldn’t get it back because of the delay caused by the State. Well, the judge agreed and threw it out.

Well, the US Supreme Court didn’t like that. Some kind of way he got reactivated and was called to active duty. And he was given the task of organizing a legal legal defenses for the Guantanamo Bay prisoners. And cut the US Supreme Court had ruled that Guantanamo Bay prisoners had the right to file Habeas Corpus petitions challenging their detention. Well, Steve David was treated like a criminal. Let him say it when he came back. They were successful to a degree but he had been accused of being sympathetic with terrorists. He had been accused of covering up for terrorists. So he he came back to give a speech about his experience of organizing the defense, for the organizing the attorneys for the defense. He was like the head public defender, for example. And he had maybe 50 deputy public defenders and he assigned to what cases was what. That was his job to coordinate the defenses for the Guantanamo Bay prisoners.

My attorney, one of my attorneys told me they had went to the conference that was sponsored by…. I can’t remember… it wasn’t the American Bar Association. It was sponsored by some other group in Indiana down in Indianapolis area. And Steve David said “now I know how it feels to be on the other side.” So he turned his back to the audience and he had a target stuck to the back of his suit coat. And he turned around the audience got it, that he became a target. And well, anyway, Indiana Supreme Court, in spite of all that reinstated the death penalty charges, saying that the State can retry me for the third time, and that I was the one. The defendant was the one causing most delays by appealing. [laughing] If I didn’t appeal, I would have been dead. What do you mean I caused most of the delays by appealing?! What is it saying?!

TFSR: I’m sorry court? Yeah, that’s terrible. I’m sorry. Also, it’s in the rule-book. So you got to do these things. You even had to go through a special appeal to be able to challenge the Supreme Court’s decision.

Zolo: Yes, they allowed it in. Yeah. But they didn’t figure that I would go file to dismiss the charges for delaying trying me within a year, they had one year to retry me.

TFSR: So they blamed you for not getting a speedy trial.

Zolo: Over three years. It took over three years to retry me. And then while we was picking the jury for the third time, the Attorney General quit the case. Let’s say they don’t want to go to trial. So they brought me a deal, in which I didn’t have to plead guilty to anything. I just refused to plead guilty. I refused to recognize the legitimacy of the court to even try me on this case. And they have been caught so many times cheating, violating their own rules, in the worst way. By plenty evidence, I still got this information. I brought it home with me. They planted evidence they falsified the ballistic tests, firearm examiner, they suppressed evidence to show that never fired a handgun, a paraffin gunshot residue tests. We also hired our own experts. We hired a ex Indiana State Police officer to analyze our gunshot residue tests. He ended up being ostracized by the Indiana State Police and Attorney General and the governor and the court system. We also hired an ex FBI agent to testify for the defense. And everything was… I proved everything. The people who came forward to help me they said was a conflict of interest, because a law enforcement officer was killed. I don’t think so. I think that these people should be commended for coming forward to speak then tell him the truth.

TFSR: Yeah. I mean, so the professionalization of expertise means that people that are experts in this sort of thing are going to get called before court, are going to become law enforcement officers or develop this expertise. Yeah, that’s absolutely ridiculous. That would basically just cut you off at the knees for getting any sort of expert witnesses to talk about the things that they became experts in because they were law enforcement officers. Yes.

Zolo: So there was a conflict of interest.

TFSR: That says a lot about how like…

Zolo: “You are not supposed to be on their side!!! You are supposed to be on our side!”

TFSR: Look at the uniform. Yeah, that says a lot about the the fairness and if they didn’t want people in Guantanamo to be able to challenge their own incarceration, then they don’t really believe in a fair legal system, where everyone gets advocacy to make logical arguments and a fair trial can occur and someone can get convicted or found innocent based on the evidence and based on the argumentation, right?

Zolo: Yes, that’s right. Yeah, that’s correct. You know, and that’s what they don’t want us to do. And now judges, the judges, I want some more. Because at the time the prosecutor quit the case was in October 2008. I think it was October 16 or October 18. I don’t recall the exact date. I think it was October 17. That’s what I think he was. I’m pretty sure of that. Well, the audience cheered. YAY! People was embracing me. My lawyers was embracing me, everybody was happy. While I was embracing one of my attorneys, I kept feeling this tap on my shoulder. So I’m thinking there is somebody else saying “give me a hug”. So I turned around and it was a judge. So I stop. The judge had came off the bench. And then he told me, he said “Oh, congratulations. Enjoy yourself going fishing.” Because I had talked about how I like to fish and he shook my hand. I though he will try to hug me. [laughs] So that was one hell of an experience for me. So then the Attorney General and the prosecutor. The county prosecutor and the State Attorney General, they said that I was intelligent and a formidable force.

TFSR: That’s probably about the nicest thing they’re gonna say.

Zolo: No, so that made us say… “okay, yeah”

TFSR: So that brings us up to 2017.

Zolo: Yeah, yes.

TFSR: I guess can you talk about what the process was like getting out? Who was waiting for you on the outside? Was there anyone waiting for you on the outside? What sort of resources did the State give you as someone they were releasing into the public? And were you coming straight from death row, just into the wider outside world?

Zolo: No, I was released from death row into the general prison population. And I did almost another 10 years in the population. I was released January 30 2009, where I was sent to RDC, the Reception Diagnostic Center. And from there, they assigned me to a prison. And I did. Then was released in 2017.

TFSR: What was what was being released like?

Zolo: When I was released from death row, it was almost like going home. It was like, this is a freedom. I got freedom. And I was treated altogether different. While I was on death row everything was a heightened security. Something’s going to happen any moment now. I was handcuffed and shackled everywhere I went. And when I got to the general population, I kept creeping in my mind that I was tempted to turn around to put my hands behind me when I saw a guard thinking that I was supposed to be handcuffed. But I caught myself. I didn’t go all the way through with it. But I had talked to other people who had been on death row with me, who had been released over the years. It was like internal organization between us. And when we see one another, we would gravitate to another one another and we ended up talking about what happened when they left, when you left, so and so eventually get executed. When you left so and so came and they put him in the cell that you was in. Some new person, he’s charged with this, charged with that. We were talking about things like that. Oh, I’d saw when you left I’d say I gotta get out of here too.

We would talk this way among ourselves. But one person who had began to slip mentally, he began to lose his mind a little bit. He was becoming more and more irrational. He finally made it to general population, but because of his mental illness it was unconstitutional. The US Supreme Court ruled to execute the mentally ill. So he made it to population and I saw him coming over to me. He began to walk, he would walk like this, scratching his chest, but he would walk like you take those little steps like he’s walking on hot coals, you know. And he came to me one day when I was in the mess hall. And I saw him coming over to me, I didn’t know what to expect and he came over and he smiled. To let me know he recognized me. And he bent down to my ear, and he said “You are a prime example of what consistency and tenacity is.”

TFSR: That’s an awesome thing to hear.

Zolo: That’s what he said. He was supposed to be mentally ill. But he had a moment of clarity and said that when he saw me. People was thinking I was crazy. Because that’s how I did. I had obsession with my case. All I talked about every day was something about the law, something about our rights, about going home someday. Didn’t know when and didn’t have a clue. Couldn’t even see daylight at the end of the tunnel nowhere. I’ve always had that in the forefront of my mind that I was going to get out of prison. I was determined to get out of prison. Not just to get off a death row, I wanted to get out of prison, I want to go home. I saw mistakes that I had made, politically speaking, that I can do good. I can do something to help people. And to be a contribution not only to the community, but to the world.

I had begin to receive more and more attention in my case. In the process of preparing for the third death penalty trial, my attorneys and I filed a petition to the to the Organization of American States, requesting them to intervene on my behalf because of the human rights violations that’s taking place. The State tried to oppose it by saying this is the common criminal trial had nothing to do with human rights. But we knocked that down because the US Constitution is a human rights charter. So you saying the US Constitution is no good means nothing? So basically, we compromised that they would drop their arguments about terrorism and did I was a member of the Republic of New Afrika or some other terrorist group. And that I would drop my petition to the Organization of American States.

And this is during the same process of picking the jury for the third trial. And during that time, they just quit the case. I was released into the general population. I got in school. I was able to fight my case the rest of the way through federal court. So in 2015, the US Supreme Court denied my petition for Writ of Certiorari saying I did not present any issues for them to review. So I just only had two more years to do. So I just use that time to prepare for my reentry.

TFSR: That reentry process, you’ve already said how it affected, at least going from death row, which is hyper security and keeping people segregated from each other and probably a lack of contact and how difficult it was transitioning from that into the wider prison population. And I would imagine it was very difficult when you got reentry into the wider non prison or whatever you want to say… outside of the prison walls. Getting used to having wide open spaces and getting used to having less restrictions on motion and also more responsibilities. Meals weren’t just provided that you had to find means to get those and also with being hampered around having a felony on your record.

I think it’s really fascinating and really awesome that not only you mentioned having this focus when you’re inside on your case, but also on helping other people and getting home and getting free. And that seems where a lot of your life has been directed. And now that you’re out, getting involved in and helping to coordinate service towards the community to end cycles of violence and help folks acclimatized themselves back into wider communities outside of behind bars. Can you talk about some of that work that you do in Gary?

Zolo: Yes, my primary interest is the cause of crime. It’s not as simple as saying, people are part of their environment. Poverty leads a person to steal and rob. That’s true also. But that’s not the answer of that particular problem. There’s something else involved. And it deals with the way people think. Their thought process. The way a person thinks is the way they act. And the system of capitalism is an immoral system and it reached reached his peak with the African Atlantic slave trade. That was the peak of capitalism, where the exploitation of people’s labor is stolen from them. And a person’s labor is not used for their own benefit to earn a decent wage or a livelihood. That was exploitation of their labor and those people who are totally exploited and their resources was used to benefit someone else and something else, at the detriment of the workers themselves.

And that was the highest level of capitalism at that time, which was imperialism. And after that, there was no other capitalism left. But there was people who made so much money, they had to figure out another way to keep this going. So they come up with the 13th Amendment. The 13th Amendment of the US Constitution says in part, that neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall exist in the United States, except as a punishment for crime. Now they got slaves again. Now they have to come up with a way to keep people coming in prison. So it’s a long range…. what word am I trying to find to describe their… long range con game. To trick and manipulate people to do what the status quo want them to do and who will keep a semi line of people fed into the prison machinery.

TFSR: I’m pulling back from times of like either conversations that we’ve had or times that you’ve spoken here about a sort of elder status, and taking care of younger people in the community, people you’ve viewed as children, not being afraid of your children but working with your children to help to sort of foster them in a very father-like manner. What sort of programs to help to undercut the pipeline into prisons in your community do you engage with? What does that look like and how are you changing minds and trying to open eyes and help people realize the tools that they already have?

Zolo: My daily activity is to practice what I preach. I walk that walk. But I recognize children, as human beings. I recognize other people as human beings. I recognize all people first as human beings and I treat them as such. Children are not given the respect that they should have as human beings. They are seen as someone who is insignificant. Do what you’re told. Stay out the way, go play. But I show the children that you are important. And you are important, not only because you are you, but you are important to the wider community. You have a say so in this community. What you say and do affects this community, if things are not going so well, you can do something about changing that. And I would give them examples. I also go into the schools and talk to the children.

Myself and Benny Muhammad in Gary, Indiana, we formed the Reentry Circle. The Reentry Circle is a transitional support group. Transitional in the sense of people coming out of prison and have somewhere to go to talk and seek support. Right now we don’t have a budget. We are operating out of our own pockets. But we are growing. So it’s not always having money to throw money at a problem. We are prime examples, living examples of that. We are doing things that we don’t even have a lot of money to do. So why do the city administration or the county, why they cannot be doing the same things? And they got the funds in the budget and the means to do it.

So we educate the people that way. Showing that they don’t have an interest in lowering the crime rate. They don’t have an interest in helping you to stay in school and obtain education. For your benefit, education for you to benefit and learn and to work and earn and live a happy life. They want you to be a brainwashed robot, conditioned to maintain the status quo. To keep things the way they are. Not for change, but to keep the money flowing. So if you commit a crime and you go to prison, and that somebody is paying for that somebody is and when and when somebody lose some money, like taxpayers, that means somebody is gaining the money. The money wasn’t just lost and blew away in the wind. The money went in somebody’s bank account. And the people whose bank account that is going into are those who runs and maintains the status quo. The State. The State consists of, not some mythical being somewhere behind the corner, the State is a combination of police officers, executives, the news media, the corporate industrial complex, and the legislators who make the laws, and the judges and prosecutors who enforce those laws. Those people together are the State. So the State doesn’t have an interest. And youth centers and the youth being able to have a voice and a say so and what happens to them.

This is how I tried to influence the young people to become better and become to take the initiative to do something about what’s going on. Martin Luther King was 26 years old when he led the Montgomery bus boycott. And when I tell people, I’m talking to young adults in their early 20s, and 30s. And I tell them that, they start to relate, now they can relate to Martin Luther King [JR], because he was a young man like them, but he was mature. And he was doing something positive and constructive. I said you can do the same thing. And I try to build up their confidence. I say “I’m not gonna tell you what to do. I’m not gonna tell you what not to do. But I’m gonna give you advice on what, from my experience what is best.” And what I say to you is the same things I’m doing myself. I say now “you’re the leader. And you lead by example. You don’t lead by sitting back somewhere in an armchair giving somebody orders to go do this and go do that.” That’s not a leader. That’s a dictator.

Those are the type of people who maintain the status quo to keep things the way they are. Who closes the schools and build and build some prisons, and then take people who are able to obtain education, and then put them in a prison that they just built at right after school just got closed down. You have to be able to learn to decipher the truth from the trick. What is the truth? And what is the trick? Closing the school down and saying that the school is not making money because there’s not enough students enrolled in the school is a contradiction by saying that the classes are too overcrowded. And the teachers can’t teach and focus attention on the class, on the students, because they have too many students. So once now you don’t have that many students and now they are saying they want to close the schools down because you don’t have enough students. Wait a minute, that don’t make no sense. But they don’t want you to think that way and be able to see what they’re doing.

It’s no different than the way the status quo is maintained. It’s no different than the mythical fantasy movie Wizard of Oz. Because once the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, the Lion, and Dorothy realized that the man behind the curtain was a human being just like they were, pulling those levers, was not all powerful, and could not be taking out of that position. The main tenets of the status quo, the representatives of the State, they are the Wizard of Oz. They are pulling the levers behind the curtains. Once you pull back that curtain, they are exposed, and people can see. And once the people see the people know what to do. You know what to do. What it takes to get things right for your own community.

TFSR: And I guess I want to ask one more question. So the way that capitalism and racialized capitalism operates in our society creates trauma, and the trauma especially impacts the communities that are on the bottom of the social hierarchy and society. So groups that are racialized as Black or brown or indigenous, queer and trans folks, femme folks, women all bear the brunt of and especially like poor folks, and a lot of that overlaps, bear the brunt of trying to survive, trying to thrive and also dealing with the traumas that they interact with by being over policed, by not having subsistence, by getting public services cut, by having their families broken up generationally, by incarceration by prisons. Can you talk about what community organizing looks like and trying to break that cycle of trauma and help people realize what those traumas are?

Zolo: First, we have to work from a premise of human rights. We must keep human rights in the forefront of the struggle in whatever we’re doing. Whatever facet of society, whatever group, friends group, marginalized group, we must keep human rights in the forefront. Whatever it is, we must first say “what are we talking about?” We are talking about human rights. So can we talk about human beings? So human beings. What are human rights? Human rights are the rights that a human being is born with on this earth. So we’re talking about a person’s sexual orientation? That’s their business. If that’s what they want to do, that’s their right. That’s their human right now. I’m straight. I don’t go that way. But somebody else does. So that’s on them. I still respect them as a human being. We’re dealing with a human being.

How was slavery justified? Well, first they had to justify by saying that these people are not human. So we can treat them this way. We can deprive them of the status of a human being by saying that they are three fifths human. Probably human? A little bit. But they’re not all the way human. They are like a beast. They’re like the animals. They don’t deserve the same respect. But it wasn’t until people start expressing their humanity, individually and collectively. You have many individual resistance where people struck back because of their humanity. You have had countless examples. But you also had collective actions, where people organized to express their humanity, such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott, of 1955. You can go on and on and on, of different examples of people expressing their humanity.

George Jackson, he was a prisoner True enough, as defined by the 13th Amendment, United States Constitution. But he was a human being. You see, they say as slavery itself, a person has been convicted or duly convicted in court of law, they didn’t say a human being. They want to avoid the word human being, because the people who represents the State, they consider themselves human. Those of us who are not part of the State, who are the poor and oppressed, we are considered some other people, some lesser people. They do not want to recognize us as human beings deserving of respect and recognition. That we should enjoy the right to live our lives the way we want and to raise and raise our children the way we want. That’s how genocides slips in. Keep human rights focused. If a person say I’m a trans prisoner, or I’m a queer, whatever you want to call themselves. I’m a human being and whatever anyone is doing to violate their rights to abuse them, you are abusing a human’s right. Keep human rights on the forefront. Human rights is got to be a front. That is up front. Always. Human rights.

TFSR: Well, I have kept you well into lunch. Thank you very much for having this conversation.

Zolo: Thank you for having me. I appreciate it.

TFSR: Before we end, is there any way that listeners who aren’t in Gary who can’t get involved in the organizing that you’re doing? Is there any a website or an email or anything where people can get in touch with you learn from what you’re doing? Or if they have some money and like what they see you doing and want to give a donation, Is there a way that they can get in touch with you all?

Zolo: Yes, well, it’s easy to get in touch with me on the internet. Just put my name in or say my name and it’ll come up. “Zolo Agona Azania Art”. You might say ”Zolo Agona Azania free from prison”. My name will come up and my information is there. My email is azaniazolo5@gmail.com – you can reach me there. Or you can also reach me at

Jumpstart Paralegal and Publishing

PO Box 64854

Gary, Indiana 46401

And you can reach me there also.

TFSR: And people can check out your art online?

Zolo: Yes, they can!

TFS: Thank you very much.

Zolo:You’re welcome.