Grief, Storytelling & Ritual in Liberation Struggle with adrienne maree brown

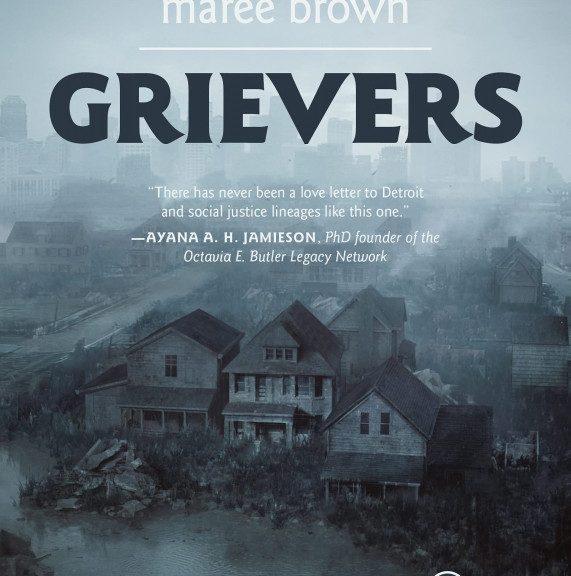

Today we’re excited to share a conversation with adrienne maree brown, the writer of such books as Holding Change, We Will Not Cancel Us, Pleasure Activism and Emergent Strategy. adrienne’s recent novella, Grievers, the first of a trilogy, was published by AK Press’ new Black Dawn imprint of speculative fiction. In this conversation, we dig into the book which is set in Detroit where a new illness that seems to only effect Black people (spoiler alert). We talk also about the role of speculative fiction in liberation movements, spirituality, ritual and grief in our organizing and holding space for inter-generational struggle.

You can support us by sharing our content in real life and on social media, more info at https://TFSR.WTF/Social!

Check out Scott’s prior conversation with adrienne on We Will Not Cancel Us.

Zine Catalog

You can find a catalog of our transcriptions to this point (Oct 2021), thanks to a zinester comrade. This could be good if you run a distro to prisoners and want to see if any zines sound interesting to them:

. … . ..

Featured Track:

- Locusts (feat. Finale) by Invincible from Shapeshifters

. … . ..

Transcription

amb: I’m adrienne maree brown, I’m a writer. I write speculative fiction, science fiction and nonfiction that is about… maybe it’s called transformative fiction, transformative nonfiction. I’m really thinking about how we transform our conditions and transform ourselves to transform the world around us. And I recently moved this year from Detroit to Durham. Although I still feel my roots in Detroit and I’m shooting new roots down into the ground here in Durham, and I’m an auntie and a Virgo and a voracious feeler.

TFSR: That’s really exciting to hear. You’re in the same state as where we’re based in this podcast. I’m over here in outside of Asheville right now. So… welcome!

amb: I keep hearing I need to go there.

TFSR: Yeah. It’s a place. There’s a lot of good people there.

amb: It’s a place. [laughs]

TFSR: It’s beautiful.

Well, yeah, I love that idea of transformative fiction and I’m also thinking about speculative fiction. I first came to your work through Octavia’s Brood which is a collection of science fiction. It was so exciting to see fiction by people who are grounded in movement work. I use the stories when I’m teaching around liberatory science fiction. I feel like from that time, you and your co editors and contributors are making the case that science fiction and liberation work go together to envisioning a new world. And then you also kind of develop that in your nonfiction by kind of like theorizing through Octavia Butler, who’s a very wonderful science fiction writer. So I just want to start kind of generally, because I know people, especially people who are committed to changing the world will sometimes dismiss fiction as not important or escapist. I wonder if you want to talk a little bit about what you think stories can do, and especially stories outside of strict realism and how they help us?

amb: Yeah. I think that a lot of people throughout history, who have been trying to organize and change the world have realized that ultimately, what we’re trying to do is change the entire narrative inside of which we live. And that the narratives inside of which we live are what allow us to either accept the oppression, accept the oppressive conditions we’re in and participate and become cogs in them, or to see ourselves in resistance to those systems, or to see ourselves as transforming and creating something beyond those systems. And Gloria Anzaldua said that “we have to dream it before we can create it,” I’m paraphrasing. I also think the work of Toni Cade Bambara and the thinking of our work as artists is to make the revolution irresistible. That always comes into play for me here because anyone who’s organized for any period of time, we learned very quickly that if we don’t have a story that people can see themselves a part of, it doesn’t matter how good our data and our facts are, right? People are not going to radically change their climate impacting behaviors, because we’re all going to die because of what’s happening to the climate. We need a story in which we fall back into right relationship with this planet and what that can look like.

So I think, every advance that we have made for human rights, social justice rights, economic and environmental rights, there’s a story in there about how humans are changing that helps us to make that advance. So then the work of writers becomes really important. It’s actually on us in some ways to figure out what are new stories that feel compelling for people to move towards a future that involves changing themselves. And that’s one of the things I think Octavia Butler did really really well. I think she is like the master class of that because she did not write easy futures. She did not write utopias. But she did write worlds where we could imagine ourselves still wanting to persist and wanting to figure it out and wanting to form the kind of relationships that could persist through change. I hope that’s the lineage that I’m picking up and that there’s a whole generation of writers who grew up reading Octavia. Who are shaped and inspired by her and by so many other Black speculative fiction writers. And Ursula Le Guin – feminist science fiction writers and other folks. I hope that that field grows and grows. I want to see lots of people who are up to movement work also writing the stories of our future.

TFSR: I love how you’re talking about that and it made me think about people sometimes talking about how we need, on the Left, some kind of myth that is compelling. But there’s often a feeling of danger with myth, because we’ve seen myth be motivated, obviously, for horrific violence and fascism. And I’m wondering if you have thoughts about myth-making. Myth is a spiritualized story in a way. It has has kind of ritual and practice, that’s often part of it. I’m wondering if you think spirituality is connected in this fuller vision of the world that our movements need to engage with?

amb: Yeah, it’s interesting, I feel like I’ve come back around to it. I feel like this past two years has really been kind of a shock to my system as an organizer, and someone who has just deeply loved and cared about humans. Watching what this last two years has looked like, and how far we are from a future in which we could think collectively and make decisions for the community and not just for ourselves. So, I have been driven back to the spiritual realm, more in this period, in the sense of, I don’t think it’s enough to have a great case and a great set of information and a great even set of practices or a road map. I think that we have to attend to the aspect of humanity that thinks of ourselves as having some kind of destiny, some kind of purpose, some kind of calling for being here. I think, if we don’t, we cede that territory to the purpose of capitalism, the Manifest Destiny, the destiny of colonial efforts which is: we constantly grow and we accumulate more and more territory and material and then we die. You’re just trying to win the game for while you’re alive, and then you’re gone. And it doesn’t matter what you leave behind.

If we have a radically different purpose, which I think we do, I think our purpose is around loving each other. I think our purpose is around finding ways to be in relationship that transcend difference, that actually created biodiversity out of a bunch of different peoples. If that’s our purpose, which does feel spiritual, to me. That work feels spiritual to me, in the sense that it is greater than the material. It’s something that happens that we could feel in the body. I feel deeply connected to ancestors who I knew while they were living, and now they’re not in a body anymore, they still shape my decision making. They still tell me things that I need to do and pay attention to. I feel very connected to those who are not born yet. Generations that are yet to come, who have intentions and designs for what this world could look like. And I feel deeply connected and driven by the non human elements of this world. I feel that the water has a design and the air has a design and the creatures all have their purposes. I think we’re the lost ones. I think the humans have lost our way inside of the greater, greater narrative.

I think in the myth piece, the thing that comes to mind… I was recently taught this wisdom that an Ojibwe elder who has since become an ancestor, Walter Bresette, shared which is that the most European thing is to think that there’s one way to do anything. When I think about that, that colonial impulse, then the opposite of that is to have many, many myths, and to live in a world in which all of them can coexist and dance with each other. I like that. I’ve read some really beautiful collections of stories of origin stories and myths that people hold for the beginning of the world. They’re all really perfectly logical for their location and their time. I think we need to create myths that feel perfectly logical for our location in our time.

TFSR: I kind of want to pick up on this thread, but grounding it more and Grievers your recently published novel, which I really loved. And because In this discussion I’m going to talk about what happens in the novel, so I guess I’ll have to put some “spoiler alerts”. But the main character who we follow closely throughout, she, Dune, is grappling with some of this stuff very specifically, especially as it comes to grief and loss. But before I go more specific to that, there is a reflection that she has on this idea of cultural appropriation in the kind of rituals that we do, and wondering what her place is in that. Thinking also about the formation of Black culture and the history of cultural theft and how she’s trying to piece things together or sees the her elders doing that and what’s okay for her to do? And I thought that discussion in your in the book was really perceptive and flexible in thinking about how cultures…. what we do. I wonder if you want to talk a little bit about that and the formation of culture in our present actions in relation to the histories that we inherit?

amb: Well, I think if you’re okay with it, I want to read that paragraph that you’re referencing. So in the book, Dune is a very analytical character. She is someone who doesn’t think of herself as spiritual at all and she’s been raised by a mother who is very spiritual, and a father who was highly analytical, both of whom have now passed. And so she’s creating this, what she thinks is a research project in her basement, about all the death that’s happening in Detroit. And her aunt comes over and she’s like ‘it’s an altar. It’s a sacred space, actually, that you’re creating.’ So, Dune is hesitant about that, because she said ‘we never had a clear lineage, and I don’t want to be…’ and she talks about that kind of grabbing everything all around me. She says ‘I don’t belong to anything, it doesn’t belong to me.’ And what Eloise, her aunt, says to her is ‘when everything has been taken, filling that emptiness ain’t appropriation it’s something else. It ain’t pure, none of it. I think of these practices, my Orisha, my altars, my prayers and chants and all this accumulation of spiritual armor as something to comfort me when my ancestral ghost limbs hurt, because I need spirits so much. I answer what calls me. Spirit is bigger than any one lineage. It comes through all these channels. It’s complicated, beautifully complicated, but it ain’t appropriation. Not amongst displaced and denied peoples. It’s different. At minimum, it’s sacred data.’

So when that piece of writing was coming through, I was very uncomfortable. It felt like it was something that was coming from beyond or coming from another place that I needed to contend with and sit with. And it felt like something that also felt true as it came through. And I feel like I have sat in rooms full of displaced peoples. Peoples who, through the process of colonization have been intentionally pulled away from their indigenous stories and their indigenous landscapes and their indigenous songs and wisdom, whatever that originally was. And not only displaced, but then the multiracial and interracial pieces start to come in. Dune is an interracial character. And most of us in the US at this point are interethnic, if not interracial people no matter how we are viewed. There has been some straying from whatever that indigenous singular identity was. So I’ve been in so many spaces where people are being called by spirit into an action, and then are catching themselves and stopping themselves and in a way policing themselves. ‘Is this right? Is this okay?’ And I think that it’s such a complicated piece of ground.

In my own life have felt myself really drawn to spaces that had an intention to be shared. So I’ve been really drawn to the wisdom of Aikido. I’ve been really drawn to the wisdom of Buddhism. I’ve been really drawn into some of the wisdom and practices of Yoga. Things where there was an intention. There were teachers who were like ‘we want this to go as far as it can. We think there’s something universal here that everyone can use.’ And I’ve always defaulted to the idea of if someone in the room has this practice that they can authentically bring in… that’s good news. But I do think we all need practices. And so I think that there’s a big question for me right now, for everyone to be figuring out. How do I find the spiritual practices that help me line up with Spirit helped me actually hear Spirit? And how do I do that in a way that is what I think of is right relationship? Where I’m not dishonoring stealing or taking. And I just love this wisdom from Elouise that it’s like ‘if everything has been taken from you, then accumulating some practices is not a bad thing. It’s actually okay.’ And I think a lot of us need some permission to find those ways. And then inside of that to figure out how do I do this without causing harm? What does that look like?

TFSR: I really resonate with that. As a person who was brought up Jewish and pretty observant, and then rebelled against it, because it felt like it didn’t align with the way that I wanted to live in the world and then recently finding community with other trans and queer rad anarchists Jews. I was like ‘Oh, we can do this in a way that works for me.’ And keep some of the rituals that I grew up with, or rethink them. It’s such a big part of me but I don’t have to get rid of it.

amb: It’s even like a thing of releasing the shame that comes from not having those things, or from having them tied to a politic that you don’t agree with. I grew up in a Christian household and going to Christian church services. And I still love more than almost anything to be in a group of people singing together. Singing spiritual music, singing hymns singing in harmony with each other. It moves me. I love praying with other people. I love laying hands on people when it’s time to heal. All of those practices still generate in me a connection to Spirit, even if I needed to move them outside of a political context that was homophobic, and transphobic, and racist, and hierarchical and all those things that don’t align with my politic. I think there is something about reclaiming the practices that are around you, and that you grow up with.

Then I think there’s also, for me in my lineage, recognizing some place it got cut off that I need to be in a worshipful relationship with the moon. But I know that I need to be in a worshipful relationship with the moon, because the moon tells me that directly. Then I can and I have, can go research and try to figure out what are the practices for this. And what I’ve cobbled together is something between what I’ve researched and learned and what I can feel called directly to. And I think that feels really important to me. That as a human being on land, in relationship to the earth, in relationship to other people, there’s some of this that we have to be able to feel. We have to be able to trust that that feeling can cut through the divisiveness that colonialism implanted in our society.

TFSR: Yeah. I think that spiritual are the ancestral phantom limbs is a really perfect way of saying saying that. I think it’s an experience that people have, who might not even identify in those ways of having lost something or knowing that they lost something.

amb: On a deepest, deepest, deepest level, I think that so much of our fighting with each other, so much of our power tripping with each other, is because we have lost that place in us that needs to be in relationship to something much larger than ourselves. There’s a part of us that needs that. And if you’re like, ‘but it doesn’t make sense to me, that’d be one white guy on a throne.’ If that story doesn’t ***jouje out for you… then it’s like ‘oh!’ What I feel like I’ve been learning slowly is that almost every people’s has some part of our story that is about being tied into the land, being tied into the actual superstructure of nature, of the natural world, and that we are not outside of that, but part of it. That, for me, has been the way that I’m like ‘it doesn’t matter what other things are going on in your belief system. If you can go out and get in relationship with the land you’re on… you’ll be heading in the right direction.’ And it needs to be a real authentic listening relationship because the land has borders and boundaries of her own.

TFSR: I want to get a little bit to like place but sticking with ritual, thinking about grief, one of the really moving parts early in the book is the extended scene of Dune doing the work of dealing with our mother’s body. Cremating her. So I’ve been thinking about this via other texts, like how grieving itself can be a political act, and certain rituals can be forms of resistance. I’m just one wondering how you think what kind of act is doing undertaking in that moment? Is it just for her? Or is it belong to the movement in honoring her mother and her father, because they’re both people who had who had been part of movements?

amb: So I think that this is a ritual. I have done a lot of reading around death rituals. And it’s so fascinating to me how recent it is that there is this economy around death. That takes the bodies away from their families, away from their home, as soon as possible. That fills them with chemicals and puts them on brief display and then puts them inside of a box, that’s going to make decomposition very difficult, and then puts them in the ground, somewhere. That’s a very recent practice inside of the long history of humans. A much more common practice, in most places, has been some variation of washing the body, some variation of sitting and honoring the body, being with the body, everyone getting to come and say goodbye. And then a process of burying the body into the dirt or burning the body, setting up a pyre pushing it into the water. But there was so many ways where it was like ‘return to nature, you came from the dust and into the dust you shall return.’ Right?

So in this story, it’s an economic resistance. Dune is like ‘this system did not care about my mom, it did not protect her did not keep her alive, and they don’t get to touch her now.’ So there’s a part of that that’s just the resistance that poor people get to have of ‘I’m not going to keep giving my body over to systems that do not care about me. I am not going to give the bodies of the people I care about to these systems. I’m gonna take her into the backyard and do this myself.’ And then I think there’s the labor of it. It’s very much Dune setting off on an individualistic path. I hope that readers see throughout the whole time that there’s all these places where Dune probably needs more people around her right now, but she keeps turning in towards herself. What happens when you keep turning in towards yourself. This is that first big move. What would that ceremony have looked like if she had invited her community members into it with her? What would have happened if she had let movement hold her in that moment? She’s not ready to do that yet. It’s also why it’s the first novella in a trilogy, because this is a long arc. I think it’s a long arc to move from that individualistic path to something more collective.

TFSR: That was actually something I wanted to ask you about because I think that’s a huge dynamic in the book – between isolation and community and the conflicting desires that one can have around that. So Dune, for much of the book, is isolated in her grief. But I think in addition to the family members that she’s mourning, she’s grieving that community that she doesn’t feel like she can take a part in or there’s some obstacle for her. Even though she was kind of born into it in a way because her parents and her grandparents were part of this community work. So this also connects to the illness and the theories behind the illness in the book. What do you think the relationship is between grief and an attempt to recover this intergenerational sense of struggle? Is there like a need to do personal work to be able to get to the community? Does it prepare us for community?

amb: One thing I wanted to interrogate was, I know a lot, a lot of people in movement who have kids. I know a lot of people who are like ‘ Oh, because my parents were movement people I wanted to do something different.’ And a lot of people, even if they ended up coming back into movement, there’s a part of them that’s like ‘I need to go somewhere else.’ There’s some natural rebellion, that natural differentiation from your parents. So part of it was I wanted to write that. You can be steeped in it, and then your rebellion is to go the other way. And so in some ways, Dune’s rebellion is to be this introverted isolated character, who comes from hyper-extroverted, deeply interconnected people. She’s never quite felt that connection, that space to get to be her authentic self.

There’s a critique of movement inside of that, that movement can have a very prescriptive way that you have to be in order to be accepted in it. And if you don’t fit in… I see people doing this contortion all the time to try to be like ‘how do I fit in and belong here?’ I want movement to be the kind of space that sees itself. All the movements that are concurrent, to be spaces that see themselves as sanctuaries for people to come and be, however we are, moving towards justice. And instead I think it can become this narrow path. ‘If you’re like this, you’re gonna get to justice.’ It becomes heaven. It’s like ‘if you just do All these little rules, you’re going to get to the utopian end game.’ And otherwise you’re cancelled! Or something else is going to happen to you. So I wanted to get permission to Dune to go about this in her own way. And then I wanted to be in an exploration of how do you authentically awaken the desire in someone for community? And then how do you authentically meet that desire with community that can actually nourish what the Spirit needs?

TFSR: In a way, that moment with Eloise is sort of a crossroads for that. But one of the main conflict of the book is that everyone that is surrounding is getting stricken by this illness. Thinking about, that still on idea of grief… One of the theories that is in the book, because there’s not an explanation necessarily of what’s happening, but it’s only afflicting Black people in Detroit. One of the theories is that the illness is some kind of accumulation of grief, mourning the movements and I was thinking about our last conversation where you were talking about how we haven’t fully grieved the effects of COINTELPRO on on the Black freedom movements. What are you trying to capture about Black grief in this book? And the contradictions? Because Dune experiences contradictions, also being interracial. What do you hope to convey about the experience of intergenerational Black movement work through that affect of grief as the main one?

amb: That’s a great question, Scott. I mean, for me, I think there was something I am interrogating around Blackness in general. Which is, there’s this expectation that we will persist and keep trying and keep living and keep creating culture and joy and magic without an acknowledgment of how much oppression, how much trauma, how much torture, how much death, how much accumulated conditions are still impacting us. So there’s never a moment of ‘wow, that was horrific what happen to y’all.’ and reparations? ‘Wow, this should not happen.’ Abolition. It’s never clear like ‘no people should have to live through this level of police killings. Seeing the data, we recognize, we need to change our ways.’ It never happens like that. So what happens is, we’re constantly in pandemic conditions. Combined pandemic conditions, depending on where you sit inside of Blackness plus your economic status, plus your educational status, plus these other things.

So, when I was living in Detroit, I started writing this back in 2011. And what I was seeing was, the city was just towards the end of this massive economic crisis. We were heading into the emergency manager period, and there was just this idea of ‘how much can you try to humiliate a Black city and act like Black people don’t know how to govern or how to manage our own budget and finances and our water.’ Just the insult of how people respond to Black leadership. And the inability to give any space for learning, right? We’re supposed to go from having no access to power to sitting in those positions of power and doing it perfectly without that space in between to necessarily get to practice what does it look like to govern in different ways. So there’s a grief, there’s shame, there’s rage, and all of that is accumulating in the Black body. And it shows up as early death.

What I was noticing around me was the Black people in my life don’t live as long and the deaths tend to be so unnecessary, and so tragic and often born of exhaustion. Things that might happen to other bodies, but we don’t have the spiritual immune system to respond to it because of how much we’re carrying. So I wanted to write about that, and particularly Detroit. I’ve had a lot of people say that they see their city in this book as well. Folks are like ‘there’s a lot of Black cities in this because there are so many similarities of what it means to be Black city in this period of history.’ But I wanted to spend some time there and I wanted to feel my way into it and feel into what does it look like to pay a debt of grief? Is it possible? Is it possible?

In this book, at least, the initial answer is even trying to begin to turn towards it… It overwhelms. It’s that much. And I think that a lot of us feel that way. If I actually stopped to let myself feel everything that me and my people are going through on a daily basis, I would not be able to go on. That feeling is always right there. Just there. You got to just push forward. Because if you look back, it’s your you’re going to get sucked into that. So I also wanted to name that and see if we can still find something compelling to help us move forward.

TFSR: That’s interesting. I’m hearing you on that idea of if you’ve stopped and let it catch up with you… I feel like that’s still an internalization of that need to be productive and a kind of individualized feeling that doesn’t actually reflect on the way that this kind of pain and death happened to individual bodies, but it’s the effect of a larger social war that’s going on. That’s creating the conditions in which people perish.

amb: This is part of it, too. I know you can’t compare pains. I deeply believe that. I know people from every kind of possible background. And what I know is that the human experience is mostly aligned and similar. Mostly we are struggling to belong. We want to feel safe. We want to feel dignified. We get hurt. We’re trying to recover. For everybody, of any background. So then inside these constructs that get set up, the whole idea of these constructs is to divide us from having these common human experiences, so that some of us can be manipulated, can be oppressed, can be overused. So that we can produce what others need. And for me, the tenderness when you recognize that just by being born as a Black person, there is nothing about me, that is necessarily distinct from the human experience. Every human is miraculous, and has the capacity for all the same magics. It’s all there.

But because of this construct that someone came up with, which again, the story, the power of story. Someone came up with a story of superiority, and because of this story an unimaginable and too heavy amount of trauma has been allowed and enacted upon my lineage. Yeah. And right now is this interesting moment where Black people are looking each other like ‘Okay, our lives matter, we’re gonna raise the bar, we’re gonna hold this standard.’ It becomes necessary than interrogate what is Blackness inside of this ‘Black matters’ right? If our lives matter, do we mean everybody Black? Monolithic Blackness? and we started to really have to name ‘we mean Black trans people, we mean Black disabled people, we mean Black queer people, we mean Black homeless people, we mean Black people with HIV and AIDS, we mean Black incarcerated people. ‘We’re really talking about all the people who have experienced the brunt of this weight. Those intersectional Blackness’s. Those are the lives that we want to center and uplift inside of this mattering. So even those kinds of conversations, there are people who are like, ‘I’m not even there yet!’ We’re in a really interesting moment inside of Blackness.

One of the things Octavia Butler always did brilliantly was say ‘a Black story is a human story. If I’m telling you a Black story, no matter who you are, you should be able to relate to it because it is also a human story.’ And I think we’re in that moment on a grand scale. The story of what’s happening with Black people, not just in the US, but globally. The story what’s happening with Black people is the human story right now. And it’s not the only human story. The story of what’s happening with immigrants is the human story right now. The story of what’s happening with incarcerated peoples is the human story right now. What we have to constantly be able to do is recognize our humanity as never, ever actually separate from those that we are trained to see as lesser than us. That’s where the path has gone astray. And that’s what we have to figure out how do we return ourselves to ourselves?

TFSR: Yeah, that quotation from Octavia Butler also makes me think. What I love so much about her work is how complex the worlds and the situations and conflicts and emotions. Nothing is straightforward. It’s always kind of ambiguous or ambivalent in ways. It made me think also about James Baldwin, and Everybody’s Protest Novel, He’s like, ‘the novel isn’t here just to send a message of Black politics, it’s to render the complexities of experience.’ And so in your book, there’s this tension between is this a Black illness, which in a way makes Blackness this simple thing. But what the illness is, is that accumulation of grief through the stories and the history. And that goes back to the way that you’re kind of parsing Black Lives Matter to not be the monolithic, we know what we mean when we say Black, but that it’s this weight of it, and it’s this history, and it’s all these intersections.

amb: Exactly. It feels important to me to note that I know a ton of Black people who have never been stopped by the police. I know a ton of Black people who’ve never been arrested. I know a ton of Black people who mostly have not even felt that personally endangered by the police. But when they start to pay attention to those numbers, then they have to interrogate ‘Okay, where in my own Black experience am I tied to that and disconnected from that?’ And what made that the case? I have a friend who was like ‘Oh, I went to an all white high school, and from there kind of moved on to a path where I was mostly socialized inside of white spaces. I experienced micro aggressive racism, but I never experienced that overt institutional racism until a later, institutional experience.’ It opens up the idea that there’s so much complexity happening within the Black experience right now, today. That’s why Black people run the entire gamut of politics. You have your Black anarchists and you have your Black Republicans. Everyone’s having these human experiences and trying to figure out ‘how do I relate to these constructs?’

I think it’s a really hard thing to want to be free of a construct. And for some people to think ‘if I deny the construct is there, I will be free from it.’ And for other people to say ‘we have to actually point at the construct, all of us together and tear it down, for it to not be there.’ And yet others to be like ‘that construct is permanent.’ All of that is happening concurrently. I get really curious all the time about that, because I can see that ignorance is bliss. I can see there are definitely some Black people are just bopping along like ‘it’s fine! It doesn’t happen to me.’ You know, whatever. And maybe it feels good inside of that. For me, when I’m denying something that is true. When I’m denying pain that is actually happening to myself or others, it actually causes me more suffering. It’s not just the pain, but the effort to hold it down. Or the effort to keep it locked behind a door. Eventually that effort becomes exhausting. So for me, I’m like ‘let’s bring it into the light and see if if we can be deconstructionist?’

TFSR: Yeah, what you just called to mind is Joy James who tries to distinguish between threads of Black feminism. There’s liberal Black feminism, there’s even conservative, and then there’s radical revolutionary. And she says ‘Black women in the position that they’re placed in our society in the US are seen as default radical.’ Even just speaking up against racism, which doesn’t need to have a radical perspective to be like ‘that’s wrong.’ That’s placed into this, ‘Oh, my God, that’s an outrageous thing to say.’

So I was just thinking about how there’s all these different ways to relate to this. To make this into a question… Because you’re writing this within the history of Black movements, and other kinds of community movements and liberal liberatory movements… I feel like one interpretation could be that these people who succumb to this illness are failures in some way. But I don’t think that’s the story you’re telling in the book. They’re not, right? But there’s not a revolutionary response, at least in this volume of the trilogy. There’s something else happening.

amb: Yeah, it felt important to me. I hope that it, as people keep reading the trilogy, I hope that it shows as a form of discipline, but I was really trying to be realistic. And what I’ve experienced every time there’s been a massive crisis is that even if people want to move straight to organizing, the part of us that needs to feel happens first. And even just this past couple years going through COVID processes, there was that first initial wave. People are actually grieving. People are losing folks and were really confused. We don’t actually know what to do. Let’s just follow the CDC even though we’re all anti capitalist, socialists, anarchists. People were like.. ‘Sure! Now, we’ll follow what they say.’

I wanted to be really humble in some of this. Because I totally got caught up in the corrective policing behavior of the beginning of this pandemic. I deeply did. I still feel the vestiges of that. I’m really trying to tease out in myself what is policing and what is protection inside of me. When I am walking out and I see someone without their mask on, the part of me that wants to be like, ‘You need to put your mask on!’ And then quickly this other voice is like ‘you don’t know what that person’s situation is! You can’t make assumptions!’ My responsibility is to keep my six feet of distance and wear my mask. What is the collective move that’s needed right now? All that still happens and I’ve been a radical organizer for 25 years!

So I wanted to be in that where we don’t always know what to do, especially when it’s happening when it’s overwhelming. And then there are organizers and what we see Eloise doing in this book is really holding the position of the organizer. I wanted people to see that even though Dune is on this individual path of her grief, organizing is still happening. People are being like ‘we need to figure out the response here.’ And one of the things that I love about Eloise is she’s like ‘we have to resist, but I don’t even know what way we need to resist yet.’ And I think that happens to us a lot. Where we’re like ‘we know this isn’t right. But we haven’t quite figured out which way we need to go.’ We get caught in the tension. Where my Emergent Strategy brain comes into this is that I think we need to be more open to the idea that we’re going to run multiple experiments concurrently. So in a way, to me, the book is that. There’s multiple things concurrently happening, and we get to see Dune’s experience up close, but there’s also other experiments going on.

TFSR: Interesting to relate it also to COVID. Initially when COVID happened I was like, ‘Oh my God! These contradictions of what we’re supposed to and do not supposed to do are gonna hit everyone and we’ll all rise up and do a general rent strike!’ Then that didn’t happen, but then the George Floyd uprising…

amb: I thought we were gonna be so clear. Eviction moratoriums and rent strike and the whole thing but then it was like… we’re not. But Minnesota turned the fuck up! They were like ‘Oh, well. We’re just going to take to the streets and y’all gonna catch up.’

TFSR:

I think that’s related. I think the conditions also what’s happened in Minneapolis wasn’t isolated to Minneapolis, but spread across the country and across the globe was in relation to the pandemic and the work that people are doing that isn’t as visible as a riot, but the kind of mutual aid care work that people were doing in the immediate effects of COVID and having to figure out how to survive when you’re abandoned.

amb: Right, and also the analytical work that people are doing all the time. I think that when something happens, when something like COVID happens, if we don’t have an analysis, then it can feel like an isolated event. Or we can be like ‘we don’t know why this is spreading the way it’s spreading and hitting certain communities the way it is and we don’t understand why these variants are emerging or anything.’ When you’re steeped in organizing, then you’re like ‘Well, I do have a sense of why and, actually, it is deeply tied back to what’s happening to George Floyd.’ Being able to make that connection of if you don’t care about the life of poor people, you don’t care about the life of Black people, you don’t care about the life of indigenous people and immigrant people, if you don’t care about the life of people who have disabilities or people who are struggling with a system, struggling with substances. If you dehumanize those people, then when something like COVID happens, that same pathway of thinking is just going to burn it all down.

Now, we’re in such an interesting place and I think Grievers in the real world are very aligned in that way. that we’ve lost a huge portion of people. It’s like ‘How do I still be normal? Now do we function? Now do we go back to normal?’ It’s a little bit more pronounced I think in Grievers, that normal is not available in the way that we currently seem to think it is. But in terms of the actual impacts, is just as unavailable to us now. What’s happening right now, it’s people who try to go about things as normal die. Then you sort of move back into a boundary, and then repeat the cycle. And because we don’t have any strong enough leadership to be like ‘actually, we’re going to change the rules, so that we can actually survive this a different way.’ We don’t have that kind of leadership.

TFSR: I mean, it’s like the negative side of running multiple experiments. Where I live, the school board just decided to lift the mask mandate in the elementary schools. And I got a kid in there. The people in the school are preparing for a spike, obviously, because this is unsafe. Everyone has a hand in this and no one’s actually on the same page.

amb: I think this is the interesting thing… From a scientific perspective, you run the experiments so that you can reach some conclusion. You gather the data, and then you apply that data. What I think has happened is that we can see the multiple experience happening around the globe. So my friend, Sonya Renee Taylor is down in New Zealand. So I’ve been watching how New Zealand is navigating this experiment versus how the US is. In New Zealand, they’re like ‘we got a case? Quarantine everyone. We’re going to track what unfolds.’ They are like ‘we found out exactly the moment that these two doors were opened in a hospital, and the Delta variant was able to move between the rooms and that’s how this person got infected.’ That’s something unimaginable that we would be tracking and be self responsive, and be able to say ‘we’re shutting everything down for three weeks until we have contained this’ and so on, and so forth.

So even at that level, we do have the multiple experiments happening, but we, as the US, is very locked in, we’re not going to learn from anyone else’s experiment. We will not let new data change our position. Which is a very American way, right? There’s really a commitment to ‘I’m going to put what I believe over any new incoming information.’ Because superiority makes you think that that can create a different reality. I don’t know if you’ve been following, but I can’t look away from the stories of people who were hardcore COVID deniers, and hardcore anti-vaxxers who are dying. I just keep reading these stories and feeling in myself, the complexity of emotions that get generated in that. Because I’m like ‘you are loved by people. There’s people who care about you.’ And in some cases people were like ‘we were fighting with them till the very end’ and they just refused to get help, they refused. And I find myself really mystified, like I really want to understand. As someone who’s in this novel writing journey, I really want to understand what it is in our human nature that allows us to create and maintain conditions of illogical danger.

TFSR: You know, I hadn’t thought about this before. But, a novel I really love is Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo, which is also about a pandemic that is about Black cultural crossover into white culture and, and when the way that Ishmael Reed talks about Western culture as a whole – it’s a death cult with a propulsion to kill everyone in the end. Even the white people who are like helming it.

amb: I write about this in multiple ways, but…There is something you know, I’ve written about this in a number of ways, but I think that there is something…. if you feel really truly disconnected from spirit, like if you are like ‘I’m not connected to something that’s larger than myself. I don’t, I can’t feel it.’ I feel my connectedness to aliveness so viscerally that nothing can take it from me. There’s no argument to it. It’s so clear in me. It’s taken a lot of work to uncover that and get into it, and trust it, but it’s there. And I think there’s a lot of people who don’t feel that. In the not feeling of that, I think the terror is so absolute, you have to almost disconnect from being connected from any desire to continue living. That death cult piece, I think there is a grand scale collective suicidality that is at play and has been!

I don’t think it’s always been that way, which is important for me to remember. This is not our human nature, because there were many, many, many, many experiments in humans that have not moved towards death, or towards war, towards violence, towards guns, towards domination. There’s all these other experiments. But how do those experiments actually survive the onslaught of those who are really obsessed with moving towards death. Because in some ways, if you’re trying to move towards ‘power over’, you’re ultimately constantly moving towards death, because you have to always be in a position of defending that power, or having that power taken from you in a violent way. And, to me, that’s the invitation of ‘power with.’ You can be in a power that is not fatal with other people.

I’m cultivating that landscape in Grievers. It’s my thing for myself. I don’t know if you’ve read Steve Biko’s I Write What I Like. But it’s a memoir, political memoir, of a South African, anti apartheid organizer that I love. But I write what I need. I write what I need. Sometimes I like what comes out. A lot of times, I’m just like, ‘Well, it’s true, or it’s honest. It’s true to me.’ And what I feel like right now is I’m like ‘I need to write something that helps me see a compelling way out of this time. Because it’s breaking my heart.’ So I’m writing from that place.

TFSR: And I feel it in the book too. You talking about wanting to be realistic and you render the world in it really beautifully and richly. I love some of the striking combinations of adjectives and stuff like that. One thing that I just pulled out was ‘the calm waves sweeping Dune’s parents away.’ Thinking about it as a calm wave, but like the motion… I think that’s interesting to juxtapose with the speculative aspect of it. It’s really physical, palpable, embodied, and also connected to the seasons really strongly in a way that’s maybe counter-intuitive too. Because hardest time is summer, and then winter is where she’s reaching out to people. Do you have thoughts about the way that you were trying to render that kind of physical embodied experience in a novel?

amb: Oh, yeah. I really wanted to pay homage to Detroit as a location and what it feels like to move through the year there and what it takes to survive a winter in Detroit. It’s so cold and it can get so isolating, and you just need people so much. I have such sweet, sweet memories of discovering how to stay warm inside of a cold place. And then sweet, sweet memories of what spring feels like after a Detroit winter, which is incredible, and enlivening. And then summer. I also wanted to capture the fact that the places that are rotting, the places that are not being tended to… the summer can be really dangerous and fatal time. And so that’s what’s happening in this book.

I think we’ve been learning a lot about the seasonal aspect with COVID. It’s been interesting. Actually, the winter is so dangerous and summer actually gives us more space. So I wanted it to feel for people like no matter when they read it, that it can feel current. Like they can feel themselves in that world and in that particular Detroit. This is my book of grief, too. So it’s a grief of a certain time and place in Detroit, a certain set of people. So I also wanted to bring it to life forever, or as long as the book exists. I wanted it to be like ‘if you need to go be in that Detroit where Grace Lee Boggs was alive and Charity Hicks was alive and Shetty was moving around and David Blair was spitting poetry. If you need to visit that Detroit, it’s still here in these pages.’ And I hope other people also write about that time and place and people. But this was my offer.

TFSR: I want to actually pick up a little bit more on Detroit because you said people reacted to the book saying ‘oh, this could have been my city.’ But in a way I felt this is very much a Detroit novel. And I just read a book, a novelization of the riots in ‘67. And thinking back then the abandonment that’s so commonly known about Detroit was happening so so long ago, right? It wasn’t just in the ‘80s. It was like that in the ‘60s.

amb: And it’s moved in waves and waves and waves. Part of it is it’s a river city and things are always moving through that city. Detroit is a place where people have survived for such a long time in the absence of what we would call ‘success’ or being a ‘successful city’. And it’s one of the reasons I think Grace Lee Boggs said that ‘Detroit is what the rest of the country has to look forward to.’ Because every city goes through these cycles in different ways. Some cities never recover from them. And we forget the names and other places continuously recover. Detroit feels particularly unique in it’s not-going-to-give-up-ness. Because there’s been many moments where it’s like, ‘Okay, I think that might be it.’ But then organizers generally keep on going. People who wouldn’t call themselves organizers. One of my favorite things when I was living there was, that would I would meet people who were doing all the work of organizing, and they were like ‘I’m not an organizer. I’m a community member. I live in this community. And so I’m doing this.’ And I think it was that spirit in that location unlocked something about persistence that I want people to know about and think about and consider.

I also think it’s like a vortex city. Like Sedona, Arizona has that spiritual vortex around it. I think there’s something similar happening in Detroit. And I want people to consider that, that there’s a reason why it doesn’t disappear. There’s something Karmically that the city is moving through and learning about its true value, which I think is in its collectivism and in its fecundity, it’s in the proximity to the water, it’s in the Blackness that has moved up from the south, up the Underground Railroad. I think it’s a sacred place.

I know we are at time, but I also want to say to people that I hope that the book invites people to read a lot more from Detroiters and about the city. I’m a student of Grace Lee Boggs and her autobiography, Living For Change, is a beautiful piece of work. But James Boggs, who was her partner, an incredible labor organizer has a ton of writing an ‘American revolutionary.’ There’s so much good content that’s come out. And then there’s people who are living and writing and thinking and creating around the city now. So I hope that it’s an invitation to people to get curious about what is coming from Detroit.

TFSR: You really feel the space and the place and the relationship to the history and the people there and a knowledge of how people live and survive. So yeah, thanks for extending that to the larger canon of Detroit literature. Well, thank you. I could talk to you about lots of different things for much longer, I’m sure. But I want to keep this succinct. So thank you so much for taking the time.

amb: I always love our conversations Scott., I really do. I appreciate you inviting me on and I hope they’re of use to the listeners.

TFSR: Yeah. And I’m looking forward to the next the next volume of the trilogy. Thanks so much.