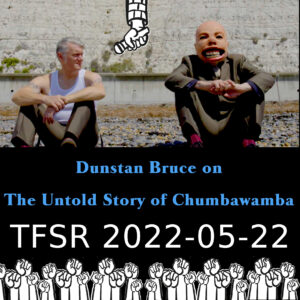

The Untold Story of Chumbawamba with Dunstan Bruce

Dunstan Bruce is perhaps most famous for his lead vocals and listing of libations in the Chumbawamba pop hit, Tubthumping. But there is so much more to him and that band than that one song. For the hour we touch on some of the band’s 30 year history, their relation as a collective, anarchist band to social justice movements around the world and how they used their fame and money to give back, Dunstan’s recently finished documentary “I Get Knocked Down: The Untold Story of Chumbawamba” and his accompanying one man show “Am I Invisible Yet?”, aging and the battle for relevance, staying involved in politics and more. “I Get Knocked Down” is still seeking distribution so not streamable, but keep an eye on the fakebook page for updates on that, and you can find his prior documentary on Chumbawamba published about 20 years ago on youtube, entitled “Well Done, Now Sod Off!”

You can find a rather embarrassing mixtape from us years ago on archive.org, expect a replacement playlist for it soon.

Chumbawamaba-related:

- Bandcamp: https://chumbawamba.bandcamp.com/music

- Wikipedia Article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chumbawamba

- Good 2012 article on the band

- Writeup on Anarcho-Punk.Net

- Interrobang!?

Some hijinks from the era:

- Miner Strike

- Poll Tax

- IndyMedia (benefited from Chumbawamba $$)

- CorpWatch (benefited from Chumbawamba $$)

- Bristol Social Centre (benefited from Chumbawamba $$)

- Radio Onda Rossa (benefitted from Chumbawamba $$)

- June 18, 1999 Carnival Against Capital protest party in London

- The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence (benefited from Homophobia Single)

- Mumia Abu-Jamal on Letterman

- BASE social centre in Bristol (benefited from Chumbawamba $$)

Other music related projects mentioned:

Dunstan’s Other Docs

Announcements

Greg Curry Hunger Strike

Greg Curry, a prisoner in Ohio serving a life sentence in relation to the Lucasville Uprising of 1993 for which he claims innocence, has just begun a hunger strike for being stuck in extended solitary confinement known as TPU at Toledo Correctional Institution. To voice concern, you can call 419 726 7977 and select choice 8 to speak to the warden during business hours, or you can select 0 to speak to the operator at other times. You can also mail Harold.May@odrc.state.oh.us requesting that his communications be re-instated and that he be able to re-enter general population.

You can find our 2016 interview with Greg at our website.

Social Media Documentary from SubMedia

Stay tuned to Sub.Media for a documentary film on the troubles with social media in early June

TFSR Fediverse Podcast

We’ve launched a temporary instance of Castopod podcasting app on the Fediverse at @TheFinalStrawRadio@Social.Ungovernavl.Org. Definitely a work in progress, but check it out if you care to.

Bad News, May 2022

The latest episode of the monthly english-language podcast from the A-Radio Network is available now at their website: A-Radio-Network.Org or here: https://www.a-radio-network.org/episode-56-05-2022/

. … . ..

Featured Tracks (get ready):

- Tubthumping by Chumbawamba from Tubthumper

- Top of the World (Olé, Olé, Olé) by Chumbawamba (single)

- Do They Owe Us A Living? by Crass from The Feeding of the 5,000

- The Cutty Wren by Chumbawamba from English Rebel Songs 1381–1984

- Timebomb by Chumbawamba from Anarchy

- I Never Gave Up by Chumbawamba from Never Do What You’re Told (Live)

- Heartbreak Hotel by Chumbawamba from Fuck EMI (compilation)

- Shhh-it by Oi Polloi from Bare Faced Hypocrisy Sells Records / The Anti-Chumbawamba EP (compilation)

- Her Majesty by Chumbawamba (single)

- Knit Your Own Balaklava by Chumbawamba from The Liberator – Artists For Animals (compilation)

- Song Of The Mother In Dept / Song Of The Hardworking Community Registration Officer / Song Of The Government Minister Who Enjoys His Work / Song Of The (Now Determined) Mother by Chumbawamba from A Pox Upon The Poll Tax (compilation)

- Smash Clause 29! by Chumbawamba from Uneasy Listening

- Homophobia by Chumbawamba from Anarchy

- One By One by Chumbawamba from Rock The Dock (compilation)

- Pass It Along by Chumbawamba from WYSIWYG

- Bella Ciao by Chumbawamba from A Singsong And A Scrap

- Here Now by Interrobang‽ from Interrobang‽

- The Day The Nazi Died by Chumbawamba from Class War

- So Long, So Long by Chumbawamba from In Memoriam: Margaret Thatcher

. … . ..

Transcription

TFSR: So would you please introduce yourself for the audience with your name, preferred gender pronouns, location, and any other things that you’d like to mention?

Dunstan Bruce: Yeah, my name is Dunstan Bruce. I’m a 61 year old man, and I’m living in Brighton. Is that sufficient? Is that enough? Actually, that’s fine. I did a one man show and that’s how the… and a film actually, both start with me going “my name is Dustin Bruce. I’m a 61 year old man, and I’m struggling. I’m struggling with the fact that we all seem to be going to hell in a handcart, etc, etc, etc.”

TFSR: So we just got a preview of the introduction of the one man show then. That’s great. I’d reached out to you first, because I and my co hosts are, and have been for a long time huge fans of Chumbawamba, and secondly, because he recently released a documentary entitled “I Get Knocked Down: The Untold Story of Chumbawamba.” So congratulations on the film release at South by Southwest. And yeah, I look forward to seeing it.

DB: I was just gonna say, it hasn’t actually been released yet. We’ve been showing it at film festivals, but you can’t see it anywhere just yet. We’re in the process of making that happen. So hopefully, that will all happen this year. But don’t go looking for it just yet because you won’t find it anywhere. We’re still doing various film festivals and stuff like that trying to sell the film. It’s a long arduous process, or it is still being a long arduous process.

TFSR: So when you say, “sell the film,” you mean getting a production company to do distribution and everything? Is that kind of what that looks like?

DB: Yeah, no, we’ve got a sales agent who’s trying to sell the film to distributors, and broadcasters, and platforms around the world now. That’s just time consuming. So we’re at that stage. We’ve shown the film in quite a few film festivals, and it’s done really well on the festival circuit. What’s happened with the film a lot is the people have, we get a lot of feedback about people really loving the film. But it doesn’t fit into any category or genre quite easily. It’s a music documentary, but it’s not a traditional music documentary. And it’s not a music documentary about the Rolling Stones or Bob Dylan or anybody else who sells millions and millions and millions of records, who have already made audiences for a documentary.

So we found it difficult to get broadcasters interested in the documentary because that world is so conservative and safe. People don’t like taking risks with stuff. And so I think we’ve made a documentary that’s quite challenging and innovative and fun. A lot of the feedback we get is that, “we really loved it,” but they won’t to take a risk with the documentary because it’s not a straightforward history of a band, really, it’s a bit more convoluted than that.

TFSR: I can imagine it’s kind of subjective. What is the format? Like how does it differ from, if any of the listeners have have have seen, “Well Done, Now Sod Off,” for instance, which was made 10, 12, 20 years ago?

DB: 20 years ago. So, “Well Done, Now Sod Off,” that was more of a potted history of the band. That told the story… a lot more of the band’s formation and goes through the history of the band up until 2000 when that documentary was finished. We didn’t want to remake that film. That wasn’t the point, going back to try and tell the story of Chumbawamba. This film is a bit more exploratory in what it’s trying to do and is less about the potted history of Chumbawamba and is more about my own story. Which means that the film has a contemporary element as well.

So we’ve taken the song, we’re using the song, Tub Thumping, you know, “I get knocked down, but I get up again” as a sort of a Trojan horse in a way. As a means of telling a larger story. So my time Chumbawamba is just part of the film, a very important part of the film, and a large part of the film. The fact of the matter is that we’re trying to explore more ideas about what can you achieve when you enter the mainstream, and what happens when that fame is over, and what do you do to carry on being relevant and being visible and being part of some sort of continuum of dissent or some sort of movement to try and still change the world? So it explores more those ideas about getting older and what do you do?

TFSR: Yeah, that’s really awesome. And I’m very glad to hear that that’s what it’s about, because that’s kind of the line of questions that I was hoping to go into. I think that one thing, like you mentioned, as a Trojan horse, it’s kind of perfect for that. There’s two big, in my estimation, there’s two big pop songs that I came across with Chumbawamba that standout aside from me delving into you alls discography ‘Tub Thumping,’ and then ‘Top of the World.’ Those really, if you say Chumbawamba to a lot of people, those are going to be the point of contact that they have. “Oh, that band that did that one song that was great in the pub, or whatever.” And that’s kind of what your earlier documentary points to, at the opening when it’s got all these newscasters saying, “Chumbawamba Chumbawamba Chumbawamba.” Yeah. Or the talk show circuit, that’s always the point of introduction.

It really allowed for the opportunity to, as other members of the band talked about, talk about politics on daytime talk shows in the US, at least in in the UK to a degree. Or be able to be featured as the opening performers at major musical events and also insert your critiques of how, for instance, new labor dealt with the dockworkers strikes or directly confront politicians or corporate individuals about their slimy-ness. I think that that seems to be one of the major positives to come out of the crack into pop music that you all made.

DB: Yeah, I mean, yes. That’s exactly right. Yes. You’ve answered the question with the question, really. I’ve got nothing to add on that. That’s like a perfect summation of it.

TFSR: I’m not a very good interviewer.

DB: [laughs] But a good critiquer.

TFSR: So, since I mentioned those two hits, and I know there were others. Like ‘Enough is Enough,’ hit the charts at some point, for instance. But can you talk a bit about the history of the band? I mean, it spanned decades. There were numerous musical styles that came up outside of what you hear in those two hits. Maybe talk about the band’s expectations of itself and how that changed with exposure and the scope, with the idea of fame.

DB: Yeah, so Chumbawamba started in 1982. We were, in those early years, those first few early years we were very heavily influenced by Crass, an anarcho punk band from the UK, who were huge, absolutely huge. They sold hundreds and hundreds of thousands of records, yet were never included in any charts or anything. They were absolutely massive.

We were really heavily influenced by what they were doing their daily lives in a commune down south in the south of England. We found their way of trying to express their politics at first really, really inspiring. They were talking about anarchism in a way that made it seem sexy and rock and roll and exciting, rather than having to attend endless boring political meetings. We just found that that was a much more interesting and exciting way of expressing our politics, and being involved in politics.

So the first few years, we were sort of influenced by what they were doing. But then we tried to make a conscious decision to step out of that movements that felt as a was increasingly becoming a ghetto of its own making. We always had this idea that we wanted to talk to the rest of the world that we weren’t particularly interested in staying in our little safe little bubble.

So our first attempt to doing that was by changing our style of music. We wanted to make a style of music that was a bit more accessible to people. The music that we were listening to was stuff that included three or four part harmonies and was pop music or it was music that used humor in a way of trying to get the point across rather than just shouting and screaming in people’s faces. We didn’t necessarily think that was the most effective way of trying to convince people that there was a better way of doing things.

So we started to change our music. We would always bring in any sort of influences that we had from the outside world. So, in the 80s we got into Irish rebel music and English folk music became a part of what we were doing. Then in the late 80s, dance music started to become a huge movement in the UK, in particular. We sort of embraced all of that. We started to make music that reflected the times a bit more. And at the same time, we sort of started changing the message of what we were saying within our music. We spend a lot of the early years complaining about everything, basically. I think we reached a point where we thought, “Look, that’s great, complaining about everything, but why don’t we celebrate some things as well?” There was an album in particular, an album called ‘Slap’ that came out at the end of the 80s that started to celebrate little acts of resistance or small victories. We changed the emphasis in the songs. We started to have a lot more fun on stage.

[Cat sounds in the background] So many cats trying to get into me bedroom, making a lot of noise and destruction. Sorry about that!

So anyway, we changed what we were doing, musically and lyrically, and started having fun being on stage and with our records. That carried on throughout the 90s. We were working together, we were a collective, and we were on independent record labels, various labels. We moved from one to another. That seemed to work as a business model, if you want to call it that. We found we were very self sufficient, very DIY, and we managed to exist as a band by touring constantly. We got to travel the world because of that.

When Tubthumping came along, that was not something that we planned. We didn’t reach a point where we felt, ‘right, we’re going to have a hit record.’ We were sort of like trundling along quite nicely. Things had gone a little bit off the boil just before we made that album. We had a couple of big meetings. We decided we were gonna give it one last shot, basically. We got to put everything into doing this album and out of that came ‘Tubthumping.’ So at the time, we didn’t realize what we’ve done, or what that song was, or what that song was going to mean to so many people. We just thought, “Right. We got ourselves back on track. We made an album that we really like. Right, let’s start trying to put this record out.”

The label we were on at the time was One Little Indian, which was actually run by some old friends of ours who used to be in a band called ‘Flux of the Pink Indians.’ They didn’t like the album. They basically told us to go away and rerecord the album or they’d get some producers in to produce it for us. So we were furious about that. We were like, “No, you’re not gonna do that. We think this album is great.” So we left the label. We just thought, “Right, we’re gonna go and put this record out somewhere else.” So we had to find a way of putting it out. So we had some old friends who used to manage the likes of Hawkwind and Motörhead back in the 70s. They took the album and basically touted it around various people and it garnered a lot of interest. So we ended up having all these all these offers from major labels from around the world to sign record deal with them.

What happened at that point was that we had no idea what we created and we made the decision, “Why don’t we take a leap in the dark in a way and sign to a major label and just see what happens?” Just see if anything amazing happens. If it goes wrong, we were about to get a huge advance, so at least we would have that money and we could do something with that and keep the band going for a couple of years just on that money. All those things happened. We signed a deal with EMI Germany, much to the chagrin of a lot of former hardcore Chumbawamba fans who obviously felt like we’d sold out because back in the 80s, or the early 90s, we appeared on this albums compilation album called fuck EMI. So it seemed like the most hypocritical thing we could have done was sign to EMI.

But that’s what we did. We had always believed that we should do what we felt was best for us and not what our audience expected of us. We always wanted to challenge everybody’s preconceptions about the band. We always wanted to do something that was interesting, and exciting, and different for us to keep us engaged in the whole process. So we signed to EMI Germany, and we signed to Universal in the States. Then obviously, the song was an enormous, enormous hit. And we had no idea that was going to happen, we had absolutely no idea. It was as big a shock to us, as it was to Chumbawamba fans. Suddenly, we had this song that was absolutely huge.

So once that happened, we had to think, “right, what we’re going to do now? What do we do with this success? How do you negotiate that?” The worlds that we were thrown into. We just made the decision that we had to make the best of it because we realized that that day would not last forever. It’s going to be a couple of years of sort of intense activity. We got to do something with our platform. Because as we thought, how often does anybody get that sort of global audience and that opportunity to speak to so many people outside of the fan base. You don’t get them opportunities, it was a once in a lifetime opportunity for us. So we decided to try and use it to be as subversive as possible and to help as many people that we could and to use the position to amplify other people’s struggles and get involved in advocating and agitating around as many issues as we could and bring those things to the fore in that in that small window of opportunity that we had. And that’s what we did.

TFSR: So a few years ago, and correct me if I’m wrong remembering this, but I recall… I want to say a few years ago, COVID has done some amazing things to our chronological memory. Maybe this was up to 10 years ago? But some members of Crass had decided to challenge legally, some of their albums being distributed for free online, because these are people that had been making music 40 or 50 years ago and they weren’t making any money off of it. Suddenly, they were saying, “Well, our stuff is out there everywhere. It’d be nice to have a little bit of money for retirement because austerity has kicked in and nobody’s making money.” So a lot of people reacted to that like, “Well, these people are charlatans, these people are sellouts. They made this music this long ago. They were handing out albums for free. Why can’t we distribute it for free?” I’m a big advocate of distributing music and art for free and also choosing to support artists when you can afford to. But also there’s a commons of knowledge and a commons of creation and no one’s building in a bubble. But I guess I’m bringing this up to ask about the question of when people were saying that you all were sellouts. Like it’s obvious that you had critiqued EMI. But what was the studio system like at the time? And how was that shifting? And where was that value of DIY and small labels coming from? Was it that you were going to change your values in terms of what you were talking about or be less accessible?

DB: We didn’t change, if anything we amplified what we were talking about because we felt as though we had a bigger responsibility to use the platform and not abuse it. So when that album came out, that was just pre iTunes and pre Napster. So we were on the cusp of all that. That big shift, that huge shift. We were just before it basically. So we were still dealing in physical copies of records, in CDs and cassettes and vinyl and stuff like that. That was still our world around that time. I think we felt like we’d made a living up to that point, largely from touring and selling merchandise and selling records on tour.

So we already had a model that we were using to keep the band going. That model never was anything to do with selling records, weirdly, because we never sold enough records for that to be a way of us making a living. We always knew we could go on tour around Europe for six weeks and sell out every night 1000 capacity venues. We were huge on this underground scene. So we were making a living from doing that. It was a small living. It was dependent on quite a few of us having partners who also had jobs, which is quite a common story of a lot of creative people. Quite often they have other people in their family unit who helped support them in that. A lot of us in the band had that and we probably couldn’t have done it without that. So we had that model that we were making a living. When Tubthumping happened, we just thought, “well, it’s not going to change anything that we say.” And really, that’s why it ended in a way because we were so determined to carry on saying and doing the things that we’d always said and done.

So, what it meant was that, when you have a hit record, you get invited to join a club. You get invited to stuff. You’re expected to behave in a certain way. You’re expected to want to be at all these parties and all these events and stuff like that. We weren’t in it to do any of those things. And so what happened with the Deputy Prime Minister, the Brits, with Prescott, that more than anything put us in a category where people became very wary of us. We stopped getting invited to stuff and we stopped getting people wanting to give us free stuff and all that sort of stuff. Because we’d broken the rules of being a member of the club. We didn’t want to be a member of that club. That’s not why we were doing it. It was not to be to become famous for that reason.

When I was making the ‘I Get Knocked Down’ documentary. There’s a scene in the film, which us all discussing what happened to the Brits. When Danbert, Alice, and Paul chucked water on John Prescott. What was really refreshing, that discussion was just a couple of years ago, everybody still thought it was really funny, really proud of it, and nobody regretted it. I thought that was brilliant that, that we still stood by what we had done all those years ago and still felt as if we were in that situation, we would have done exactly the same thing. Because we weren’t careerists. It wasn’t our club. Why would I want to be a member of that club? I just didn’t want anything to do with it. We will never about just wanting to be hobnobbed with celebrities. That’s why we took a couple of dockworkers with us to the Brits. So, if we’d won the award that we were up to, they would have gotten up to pick up that award and have the opportunity to talk about their strike. As it was we didn’t win the award. But, because of what happened, there was a lot of publicity around that.

That felt really good. In fact, in the film, not to give you any spoilers, but I go and talk to Penny Rimbaud from Crass and he just actually said that that’s the moment at which he thought that we absolved ourselves, by doing that thing to Prescott. He said, “Nobody else would have done it, and nobody else could have done it.” He was like, “Yeah, I thought that was brilliant, and that made everything as you did feel worthwhile.” And it did to us as well, it really did.

You know, we were doing a lot of stuff as well that nobody knew. We were giving money away all the time to a lot of different people. We were raising money for different people and talking about different struggles all the time. So our politics didn’t change in the slightest. It just meant that we were in a situation where we could talk to a lot more people about us the music. To go back to the stuff about the the music for free and all that sort of stuff that never really became a thing in our world. We did put out a free CD or something that was critical of drummer Lars Ulrich trying to take somebody to court or something because they’d downloaded some Metallica music illegally.

TFSR: I think they were on Sony or something.

DB: I just thought that was ridiculous that they would do something like that to a fan. It was a fan and they tried to sue a fan. It was just the most hideous thing you could do. We were appalled by that. I think we’ve always been sort of early adopters of technology and acknowledged that once something like that starts, once the lids took off, you can’t put the lid back on. That’s it. It’s “Boom. That’s it.” I think it was like that with Napster and then what came after that. You can’t have any control about that. It took a couple of years for everything to settle down again. I think now people have a much more responsible attitude towards what you pay for and what you don’t pay for. Stuff like that. I think it’s a lot more. It’s just how it is.

I suppose I have a similar approach to you, there are some times where I will just ask a friend to find a film because I can’t find it anywhere and it’s been gone at the cinema and I just want to see it. I think, “Okay, I’m making a decision now to watch that film and not pay for it.” But then on the other hand, I buy stuff that I’m not even gonna listen to because I really believe in it. A friend will put out a record and it’d be a benefit record and or whatever. I just think, “I’m gonna buy that. I’m not bothered about listening to it.” I’ll listen to once, maybe. It’s not like something that I’m listening to over and over again. But I just think you make those sort of decisions, what you do, who you help, and who you support, and all that sort of thing. A lot of what I do now is live, either live music or live theater. So it’s stuff that you have to come to anyway to experience.

I think what I found when I got a new band together, Interrobang‽, one of the things I loved about Interrobang‽ was as much as I loved performing, and loved the music we were doing, I really believed in it, but what I really loved was getting back into that that scenario where you go to a gig and you’re part of a community again. I think now more than ever, because of what’s happened in the last couple of years, that just feels like really, really important that we come together and share ideas or just have fun together and have this sort of communal experience that we’ve been robbed of for quite a few years now. So the live experiences, I still think that’s one of the most… I don’t think listening to a record, for me, I don’t think listening to a record ever compares to a live experience.

So, and weirdly, I used to think that about Chumbawamba as well. I was never I was never that involved or passionate about the making of a records, or a Chumbawamba album. I knew that there was people in the bands who were brilliant at producing records, and I knew there were musicians in the band who were brilliant at putting all the music together. I was one of the vocalists. I really, really enjoyed that. But for me, nothing was better than Chumbawamba playing live. That, to me was where all the magic happened. It was in a live situation. I think we all used to really, really love playing live because of that, because the gigs were like, they were like huge celebratory events. And when I go and see bands now and you feel that it’s an amazing experience.

I’ve been going to see Patti Smith for over 40 years now. I still absolutely adore her. When I go and see her it feels more than just a gig to me. It’s like a place where you replenish your soul in a way. And for me, recorded music doesn’t do that for me in the same way, I suppose. So I sort of sidestep that big issue about Spotify or iTunes or Amazon, whatever, however people listen to music now, because to me, where I get my energy from is from performing live or seeing other people perform live. I think that, to me, is where the magic happens.

TFSR: It seems like, if the question is, “do you support an artist in their ability to create art and to share that and record it?” You can make that decision to buy a t shirt or send them some money or do whatever without actually going through the record company that makes a huge amount of cuts. And there are individuals that do the recording that work for the studios that get paid by the record labels and such, but it seems like through your experience, the studio system, or the way that musics distributed has shifted like two or three times and sort of changed the social rules.

I was kind of hoping to get back to that question of how you all related to movement and where money went from some of the success that you had. I mean, even before that you you all did at least one performance that’s in that documentary, the ‘Well Done, Now Sod Off,” showing you all performing at the miner strikes in ’84. So you clearly had been a part of movement, besides the content of your music, talking very frequently about issues around gay rights around anti racism, anti fascism, and definitely focusing on capitalism a lot. Could you talk a little bit about how Chumbawamba used its resources and its reach to support things like the 18th June Carnival Against Capitalism, or Indymedia? Could you talk a little bit about that?

DB: Yeah, I suppose. To catalogue Chumbawamba’s timeline, we started off in the 80s and we were doing lots of animal rights benefit gigs, anti nuclear war gigs, we were involved in a lot of small campaigns at that time where we would be doing stuff for anarchist groups. When the Miner’s Strike came along in ’84, that was sort of a massive shift in people’s politics. Because up until that point, I think we’d regarded ourselves as anarcho-pacifists in a way. So a lot of the causes that we were involved in were to do with animal rights and stuff like that. When the Miner’s strike came along, that was this idea that that was a class issue, and it was a class struggle. And we shifted. Our politics shifted, but also the sort of benefit gigs that we did started to shift and we widened our horizons.

So we found that that meant that we stopped being so isolated in our anarchist politics and started to get involved with working with other left wing groups and organizations and with people whose politics weren’t exactly the same as our own, but that we had enough in common with that we realized that there was some sort of common ground and that was sufficient for us to work together or to raise money for quite different organizations. Britain in the in the late 80s, there was all this stuff around the Poll Tax, which was this unfair tax that the Tory government were trying to bring in. We did a lot of gigs around raising money for protesting against that, and demonstrating against that.

Then, if you look at Chumbawamba’s back catalogue, in the early days there would be a single there was about fighting an abortion bill or a bill – clause 28, clause 29, which was basically anti LGBTQ. It’s sort of rearing its head again, nowadays. Both of those things are. We’d be touring a lot and things would come along and we got involved in the early 90s a lot in LGBTQ issues because that’s what people in the band were just like, it was part of their everyday existence. And so it just became a natural progression that we were then putting out singles. We did a single called ‘Homophobia’ in the 90s with the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence. They were this gay nun organization. There was stuff like that. So, when Tubthumping happened we’d done a massive benefit for the dockworkers. So it only felt natural that we carry that on into a bigger platform. But, you know, we’d gotten involved in the Mumia Abu Jamal campaign and so that’s why when we went on Letterman, we changed the chorus to that. Stuff came along.

I don’t know whether you were alluding to this but it’s an interesting story anyways, this was after Tubthumping. We used to get offered stupid amounts of money for people to use the song in an advert. That was a new world to us. We’d never experienced that before really. General Motors wanted to use the song in an advert for a Pontiac car and we turned down loads of stuff. We turned down money from Nike, we turn down money from General Electric. We were making those sort of decisions all the time. But then this one came along. We just thought, “Look, why don’t we take the money for the advert and then just give the money away?” So what we did is we found Indymedia and CorpWatch.

CorpWatch was this organization who monitored the bad working practices of companies like General Motors. So it seemed really appropriate that we give the money to them to criticize the behavior of General Motors. That was quite an interesting process because we got in touch with both Indymedia and CorpWatch before we did before we agreed to give a song for an advert. It took a little bit of persuading for those two organizations to accept the money, to agree to accept the money once we got it. They were both a bit like… CorpWatch more than Indymedia actually, we’re a bit like, “I’m not sure. Is that ethical? You’re getting money for this, and then you’re giving it to us.” But in the end they both agreed to accept a share of this money.

So what happened on the back of that was we then turned that into a newsworthy article. It garnered press from the fact that we’d even done that. It was some clever Situationist prank that we’d turned that idea on it’s head that we’d got money for an advert and then given the money away to criticize the thing that we were advertising. So we liked that. We liked that idea. We got money for, I can’t remember what it was. It might have been a martini or something. It was some drink or something. Anyway, we gave the money from that to an Anarchist Italian radio station or something like that. We were always finding opportunities to use our position to further causes that we believed in. I think we felt in a lot of cases that we were giving voice to the voiceless in a way and were being able to use our position to further the causes and stuff that we believed in. People who would never get the chance to be on national television to talk about their particular cause.

On top of that, we used to give away a percentage of the money that we made to various organizations. We’d have these meetings where we’d have a list of all these people who had asked us for money and we decide. Then we’d split up a certain amount of money every three months and give a lot of money away. Just because we thought that’s paying back all these organizations and people who have supported us over the years as well. We were suddenly in a position where we can do that, and it felt worthy, it felt really worthy. But at the same time, it was just like, “this is brilliant. We were helping.” I still occasionally hear from people in Bristol. We helped these people in Bristol buy this building to set up a social center. And I still get messages from them saying, “Yeah, remember when you did that?” It’s funny, because at the time, it was probably just another thing that we helped. But to those people, it meant the world. It was amazing opportunity to do that sort of stuff.

So I think what was interesting about going back into that environment with a new band was that there was a lot of goodwill. There was a lot of goodwill for what I was doing. I was doing something DIY again and trying to be involved in a movement on a grassroots level again. And that was the level that when we had all that fame and fortune, it was the very people we were trying to help way back then. So it was a nice circular thing that came around, it felt really heartwarming.

TFSR: Do you mean with Interrobang‽

DB: Yeah. Because Interrobang‽ was always just a small passionate project that we had. For a few years shone quite brightly in an independent DIY music scene in the UK. That felt really great. There were so many people I met from years gone by, from during the Interrobang‽ It felt like such a positive experience being part of that community again. I’d drifted away from all that. This is the thing about making the film. When I started making the film, I was in quite a low place. I was wondering, “What I was doing with my self, how do I fit in to the world?” And what happened was that it then became quite a meta sort of thing. The making of the film itself became the thing that got me out of my quagmire, in a way. It was the thing that helped me. So it was in talking about the things that I was trying to resolve, that I resolved those things, if you see what I mean? It helped me just doing that. And that led on to me doing the ‘One Man Show,’ which is a very similar thing, you know. So the act of creating the film helped me move on. So that was a really positive thing for me.

TFSR: Yeah. And so you’re still doing performances of ‘Am I invisible yet?’ Could you talk about that experience and sort of like another way of reinvigorating this relationship with the audience by doing live shows and how it sits alongside of the documentary?

DB: Yeah. The One Man Show came out of the film in a way. The previous two years, when we were locked down or whatever, it was quite a creative time for me in a way because me and Sophie, who I made the film with, we managed to finish the film, editing remotely with various editors. We got the film finished. Once we finished the film, we did have a discussion about what we were going to do next. We had a brilliant time making the film together. She’s from a completely different background. She’s an amazing filmmaker. She brought a lot of her talents and skills to the making of the film. I brought a lot of my…just my history, and just having stupid ideas that she would then make work. That was a really brilliant process.

When we finished the film and I saw it. I said to her, “Do you think we’ll make another film together?” And she said, “No, I don’t think we will.” And at first I thought I was like completely shocked and offended. I was like, “why would you? Why would you not want to make another film with me?” And she said, “Well, because I think what we’ve learned is that you need to be on the stage or you need to be performing somewhere. You’re much better at that than you are being behind the camera.” And she’s right, she’s totally right.

At first I was offended that she didn’t want to make another film with me. But then what happened is that she said, “Look,” I said, “Right, well, what should I do? Well, I’ve started writing this, a one man show.” And she was like, “Look, I’ll direct the one man show.” She used to work in a theater years ago. She said, “I’ll direct it. You write it, you perform it, I’ll direct it.” And that’s what we did.

What the one man show enabled me to do was take a lot of the things that are in the film, about reaching a certain age about starting to feel as though you might be invisible and wondering what your place is in the world, and how relevant you are, and how do you keep on trying to be part of a movement where you try to change the world, and you keep on doing that. So we took a lot of those things from the film. I brought them into the one man show as well as combining a lot of the Interrobang‽ stuff. Because what had happened within Interrobang‽ was that that had sort of ground to a halt. And, for one reason or another, we had stopped. We couldn’t really do any more shows. Harry had stopped doing it. He was a member of Chumbawamba and was also the drummer in Interrobang‽. He had to stop performing because he had to care for his partner who was not well. Griffin just couldn’t find the time. Griff has a young family and he couldn’t find the time to commit to the to the band.

So I had to find a way of expressing myself still. So what I did was I took all those elements of Interrobang‽ in the film and turned it into this one man show performance, which is like music, poetry, prose, film. It’s a combination of all these different things and it’s me performing this thing that goes on for about an hour. It’s worked out really well. It has become a really positive thing. That is also something I’ve never done before, performing that way. I’d always been in a band. So the idea that I was stepping out of my comfort zone and doing something that I thought was terrifying, meant that I was keeping that creativity alive. This felt really important to me.

When you get to a certain age it’s harder and harder to be part of a creative world. Just because there’s a lot of other things going on the take up your time. And there’s less and less of a place for you in the world that seems more towards youth and for the people who are well known anywhere, who have the have the funds to do whatever they want in a way. I didn’t solve up that, but I found a way of doing this that I’m really excited about and that really stimulates me. So the idea that we’re going out and doing this show, where I’m basically saying, “Look, am I invisible yet?” We’ve all had that feeling, everybody, that’s not just me, that’s all of us, everybody has had that feeling that they’re becoming less relevant and what do you do about it? So the whole idea of the show is to not feel alone, in a way, which I think is really important.

To feel as though you are still part of a movement or a community. I keep on banging on about movements and communities because I do think that in a world where it’s really hard to affect any sort of huge change in the world, I think we have to always find those small victories and those little things that really keep us going. The fact that we embrace different adventures and that we don’t give up and we step outside of our comfort zone, I think it’s telling us stuff like that. Part of the show is about this idea that we just have this one go at life. That’s it. This is our one go. I just feel as though you can’t waste a minute of it, you’ve got to do something with your time here. But you’ve got to enjoy it as well.

I think I got sort of depressed about the fact that there was a time when it felt that you were obliged to go on demonstrations, you were obliged to be part of various political actions, and you were obliged to be angry on Facebook or Twitter all the time. I think I took a step back from that, because I realized that it wasn’t a particularly healthy way of going about things. So I made all these decisions about approaching all of those sort of things in a different way. Which was really good for me, and it’s turned out really positive for me, I suppose.

You know, in making the film, what’s really encouraging about that is that there’s a lot of love for Chumbawamba in the world. Even though we felt at the time that everybody hated Chumbawamba. that there was only a small amount of people who actually liked us. I’ve sort of realized over the years that that’s not the case. There’s a lot of love out there for the band. And that’s a gorgeous thing for me. That helps me feel as though, “okay, I’m trying to do something now, but that still resonates for a lot of people.” That song was 25 years ago now, and that is still resonates for people.

Like, last week before we did the ‘One Man Show.’ Sophie and I went leafleting in Brighton to try and get people to come on to the show. It’s a thankless task, leafleting, there’s no fun in it at all. Sophie started doing this thing, where she’d give people leaflets for the show, and I’d stood behind her, and she just go, “Do you know who he is?” And then then they’d go, “No?” And then she’d go, “He’s the guy from the song. He’s the guy from the ‘I get knocked down’ guy.” And honestly just middle aged people just be like, “No way!” And they’d be absolutely delighted and they’d have a story about how that song was still resonating now.

There was one couple who Sophie did this to. One of them, in his phone, he showed us his phone, and he calls his son ‘Tubthumper’ on his phone, because 25 years ago, they were really laughing about when he was a little kid he just used to fall over and get back up again. So they called him ‘Tubthumper,’ and they still called him that. So it meant something to him, it was just really funny. Then we met these other two guys, and they were the same. They had this whole story about 25 years ago, what that song meant to them and stuff like that. It’s just that. To me, that’s really touching. I really liked that and it made that whole experience of doing something as excruciating as leafleting, I felt that day I’d sort of achieved something just by finding some common ground with these people. All they wanted was a selfie with me. That’s all they wanted was to take a photo to send to their mates and say, “look, look who I’m with! This guy.” I don’t mind.

I don’t mind about that in the same way that I’m not in the slightest bit embarrassed or ashamed about the song. I’m really proud of the song. I’m really, really proud of it. I know it ends up in lists of the 10 most irritating songs ever written. I don’t give a **** about that. I don’t care about that. Because I know that there’s people out there that that song just means something to. That is the power of music. I love that. I love the fact that music can be such a powerful force for good. You can bring people together in that sort of way. I think that’s a brilliant thing. So I’m really proud of that. I’m really proud of this song. I don’t think it’s Chumbawamba’s vest song. I don’t think in any way it is. But I love it for what it has enabled me to do on the back of it and the way it’s touched people’s lives in completely different ways. We get we still get letters from people saying, it seems really inappropriate, but people play at funerals. It seems like such a strange choice.

TFSR: Praying for the resurrection, I guess?

DB: Yeah, yeah. Yeah, it was. But it gets played at all these weddings, birthday parties, all sorts of stuff where people are like, “oh, yeah, that was my song. I remember that song. blah, blah, blah.” I think that’s great. To enter popular culture in such a way, I think it’s something that Chumbawamba always hoped we would achieve. That we would be that we would be able to leave a footprint. If that means that people go off and find other stuff, other interesting stuff, or get involved in other things, I think that’s a really good thing. At its lowest common denominator point, people really enjoy the song and I have a really good time dancing to it and stuff like that. It brings back really good memories for people. In that sense, I’m really proud of it.

TFSR: I’d like to know a little bit around how you feel about, how mostly anarchists as a movement as a gaggle of freaks, we tend to sort of shun the idea of people taking space and being public. Fame is a weird thing definitely among anarchists, among punks, and these variant and related groupings. Some times we will revere an individual or group and their contributions, and at the same time, I think we have a pretty healthy aversion to putting people too much on a pedestal, or making too much out of them.

I wonder, for you, obviously you mentioned the contribution that it’s giving you a connection to people nowadays who you would not have met if you just stayed playing an anarcho-punk stuff that’s fun for me to listen to, but a lot of people like my parents would just kind of cringe a little bit at, then 20 years later, having a one man show called ‘Am I Invisible Yet?’ I guess I’m wondering what sort of insights you have about intergenerationality and social and political movements and how you keep involved and how you try to engage with younger folks and bridge that gap? I think social movements have to be, if they’re going to be contiguous, if we are actually going to change the world in the way that you described, It’s going to take not just one flash in the pan, one really good pop song. So how do you stay involved, or what sort of difficulties have you found of keeping engaged besides being busy with work and with family and stuff like that, with new people coming into movement?

DB: Yeah, I think what happened to me was that I sort of dropped out of all that. That was because I had kids, little kids. They became my focus, and trying to decide what I was going to do after Chumbawamba. That was quite a difficult time for me. I think what happened was that I started working with a band in Brighton called The Levellers. The Levellers were huge in their own way. They’ve never been particularly mainstream, but they’ve got a huge following. I made a documentary about them. I was sort of friends with them years ago and I met back up with them and then I made a film. I worked for him for a while and then I made a film for them. That sort of showed me that there was a lot of people out there who were growing old, disgracefully or gracefully, but still being involved in political movements and still doing stuff.

But what was interesting was that their children were coming to Levellers gigs as well. There was this whole new generation where these parents were bringing their kids to gigs. I found that really interesting, that they are influencing their kids and the kids are getting into their own their own stuff and finding something in this not in a nostalgic way. The parents are doing in a nostalgic way, but to this new generation, it was something new. So I found that quite interesting. But then, I met various people on the back of that, and then that led to me meeting other people and other bands that were still doing stuff that were my generation.

But then this movement sort of blossomed in London. Well, it felt like it started in London because a friend of mine, Cassie Fox, set up this thing called ‘Loud Women,’ and it was a response to the fact that festivals were like 90% Male performers and there was such a small space for women to get up and perform. So she basically set up her own festival with a few friends called Loud Women Festival. I didn’t become involved in the organization of the festival but I became involved in that whole thing that was going on and became friends with a lot of the bands that were getting involved in that.

I just found them really inspiring because it was this younger generation of women who were finding their voices and finding an outlet to express themselves in such a way that just felt really powerful. This was at a time, this was sort of post Pussy Riot getting a lot of publicity for what they did in the church, the Orthodox Church thing. And so I just thought, “This is this is amazing. These women are finally finding a push to kick open the doors, in fact, and have found a way in and are taking back control.” It just felt really ****ing inspiring. At that time, this idea of being an ally became a big thing and I just thought, “yeah, the timing of all this is brilliant.” I felt at that time that my role was to be an ally with everything, to help in whatever way I could and get involved in a way where I wasn’t trying to take the limelight. I completely felt inspired by these people.

Then, of course, there was stuff like Greta Thunberg, and Tamika Mallory, and Ella Gonzalez. There was all these young women who were becoming really vocal and visible. I just thought there’s something happening here that I felt hadn’t happened before. It felt like a moment where things shifted massively, where I was now an older white man who was now getting his inspiration from a lot of other other younger differently gendered people. I just thought, “this is brilliant, this is really great.” It really energized me. It really made me think, “yes. There’s a movement here, and there’s a lot of people!” It felt voluntarily underground and it didn’t necessarily want to be mainstream. I thought that was a really good starting point for people finding their voice and finding a movement to be involved in.

That ‘Loud Women’ thing is still going strong. A lot of brilliant stuff has come out of that. That’s brilliant. That was something that I bring up in the film and I also bring up in the One Man Show, that that’s happening. For once, what’s happening is we’re not looking to an older generation for the answers. We’re looking to the younger generation for the answers. This whole thing, a friend of mine coined this phrase ‘generation left’ which is this idea that the younger people are more likely to have left wing politics and express left wing ideas. It’s my generation that become more right wing and more middle of the road. All that made me think was, “Don’t ever let yourself fall into that trap of being middle of the road.” Just always be aware of what’s going on around you.

Lots of stuff that’s going on with that younger generation, I admit I can’t keep up with it all a lot of the time. My daughter is 19. She’s absolutely all over it. She understands the subtleties of it, of everything to do with that generation inheriting a world that’s an absolute **** show. The way she talks about stuff and the passion she has for what she believes in, I find that really inspiring. I like the idea that you never stop learning. The fact that you’re learning from a younger generation. I remember being her age and even a little bit older and just been been so idealistic. And so determined I was going to change the world. I find it inspiring that that the Zoomer generations who feel like that. All that climate change movement that came about a few years ago, I thought that was a brilliant starting point. It’s one of the biggest things that is is going to kill the planet. I just thought that was brilliant that that was such a huge rallying point. And seeing young people get involved in the Black Lives Matter movement, to me, it was just incredible.

When I was that age, we had anti Nazi League and Rock Against Racism. Those were things that politicized me back in the 70s. That’s where I found my politics, through the bands I was into and what their politics were. So it was stuff like The Clash doing Rock Against Racism gigs and me working out what that was all about. I thought, “All right. Yeah! Yeah, I agree with that. If Joe Strummer thinks that then there must be something there.” Then you go off and you form your own ideas and stuff like that. But the jumping off point was like bands who are saying stuff. Now I think there’s a new generation of bands who are doing that again. Sorry, I waffle on.

TFSR: It wasn’t waffling. But yeah. And I think for me, and I’m in my 40s, I’m no spring chicken, I think it’s super inspiring personally, to see for instance, the Black Lives Matter movement, or the Movement for Black Lives, the Anti Fascist organizing that’s been happening in my country visibly in this last wave for the last seven years or so. That stuff is built on what was there before. Before people were calling themselves Anti Fascist here, there was Anti Racist Action, there were other groupings, and you can just look back for inspiration. Though the struggle might look different at a specific moment, there’s so much still to learn from how there were people doing Earth First and ELF and ALF actions that you were talking about in the 80s and 90s in the UK. People doing XR, you can bring a lot of criticisms to it, but a lot of action to try to bring attention and stop the Ecocide that’s going on now. Just like you had National Front at a certain point, and then, National Action, people were fighting both of those movements.

There’s a lot that I think every generation can get from being able to tap someone on the shoulder from a prior generation and say, “you saw something like this, how did you fight? What mistakes did you make?” And sort of learning off of that. That that’s kind of what I feel when you’re talking about your daughter’s interactions and the current feminist uprising. It’s super inspiring to be able to look back and forth and see that we’re not just alone.

DB: Yeah, in all the stuff that’s happening. That feminist surprising that you talked about, to me, it’s really inspiring because I think there was pushback against that massively. An almost anti feminist sort of moment. I think there is people that have been vindicated in continuing that struggle. There’s so much stuff that’s happened. Even all the ‘Me Too’ stuff and what that has exposed. It’s incredible. My laptop is gonna die in a minute and it’s half past four now. I might have to go. Is that okay?

TFSR: Absolutely. Yeah, and thanks so much for taking the time I’ve really enjoyed it. I of course had more questions, but I could have gone on all day. I have work in a half an hour. So by saying, “I could go through all day.” I’m not going to ask you to. But Dunstan, it’s been a real pleasure speaking with you and I look forward to getting to see the film once it has distribution. Where can people find out how to how to get a hold of it? Do you have a website or social media presence that you want to point people to where you will be announcing when it hits the screens where people are at?

DB: Yeah, I’m useless at all that sort of thing. I think there’s an Instagram? There’s a Facebook page or something like that. I’m really bad at social media. I’m even really bad at it.

TFSR: It’s terrible. It’s bad to us. I’ll find the links and then I’ll put them in. Well, hey, it’s been a pleasure. And I hope you enjoy the show tonight. And again, thanks a lot for chatting.

DB: Yeah, check out Bob Villain. He’s doing really well over here. But he’s quite interesting. I’m interested in seeing him tonight. I’m excited. Alright, Ok. Cheers.

TFSR: Cheers. Okay, thanks a lot. Ciao. Bye.