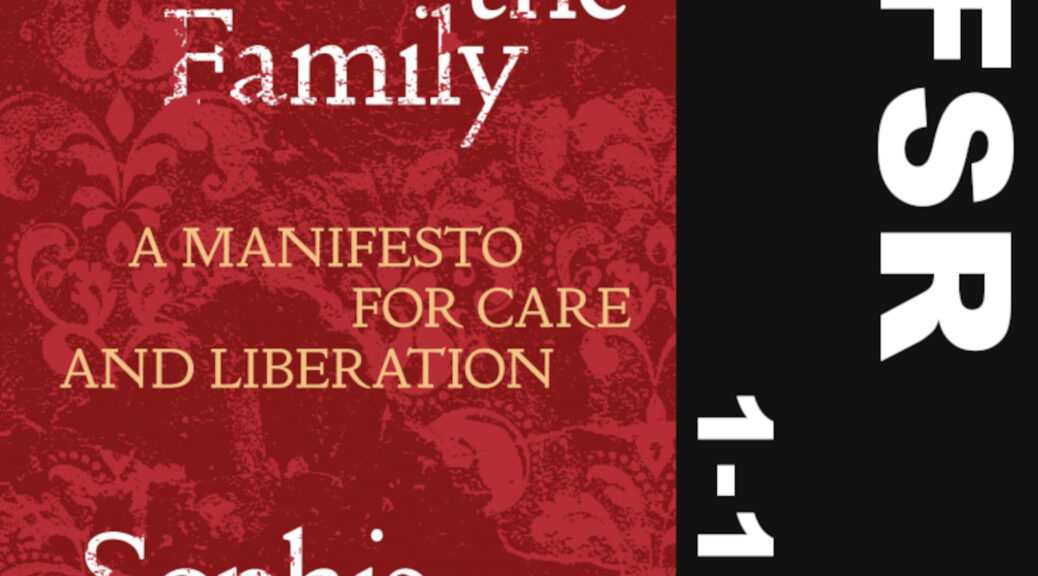

Sophie Lewis on Abolishing the Family

I’m sure that many people coming out of this holiday season, returning from visiting relatives will wonder: “couldn’t we abolish the capitalist family structure?” We’ve got great news! We’re happy to present this conversation between Scott and Sophie Lewis, author of “Abolish The Family: A Manifesto of Care and Liberation”.

In this episode, Sophie speaks about the book, the ideas and inspirations she’s pulling from, the critique that the family form not only passes property and generationally allows concentrations of it, but simultaneously limits our horizons of care to these small, private and often abusive relationships. Here we also find ideas of Child Liberation, a challenge to the state form and capitalism, and an invitation to imagine beyond what we’ve been taught is the natural nucleus of human relationships in what turns out to be a long lineage of ideas cast back through Black feminisms of the 70’s and beyond.

Anyway, there was a lot here and we hope you enjoy. For a related chat, check out Scott’s July 10, 2022 interview with Sophie on the show, and you can find more recordings and essays at her site, LaSophieLle.org and support her freelance writing on her patreon.

Next Week…

Stay tuned next week, possibly for a chat between Scott and Rhiannon Firth on their recent book, Disaster Anarchy: Mutual Aid and Radical Action.

Announcements

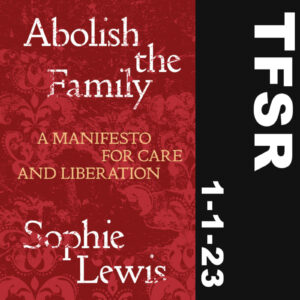

Blue Ridge ABC Letter Writing

If you’re in the Asheville area, Blue Ridge ABC will be hosting a letter writing at Firestorm Books on Sunday, January 8th from 3-5pm. Usually, this’d take place the first Sunday of the month but that’d fall on New Years Day and that didn’t feel realistic.

If you’re in the Asheville area, Blue Ridge ABC will be hosting a letter writing at Firestorm Books on Sunday, January 8th from 3-5pm. Usually, this’d take place the first Sunday of the month but that’d fall on New Years Day and that didn’t feel realistic.

Colombia Freedom Collective

There is an urgent fundraising appeal from the Colombia Freedom Collective as trails approach for the Paso Del Aguante 6, political prisoners from the uprising against police impunity and murder in 2021. You can learn more at ColombiaFreedomCollective.org

. … . ..

Featured Tracks:

- It’s Like Reaching For The Moon by Billie Holiday from Lady Day: The Complete Billie Holiday On Columbia 1933-1944 (CD1)

- War Within A Breath by Rage Against The Machine from The Battle of Los Angeles

. … . ..

Transcription

TFSR: I’m really excited to be talking with Sophie Lewis today about their new book Abolish The Family: A Manifesto of Care and Liberation, which is out now with Verso Books. Can you introduce yourself with any pronouns and any affiliations that you want to name?

Sophie Lewis: Yeah! I go by they and she. I have a visiting scholarship that’s unpaid at the University of Pennsylvania in the Gender Studies department. So I have a login for my academic writing and for research purposes. And I teach at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research as well, teaching online courses on critical social theory. Those are the two affiliations I’d mention, I suppose.

TFSR: In your first book, Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism Against Family, you’re already critiquing the family. I was really interested in that book and how you talk about it now, in the new one. This time, you’re going full throttle “abolish the family.” But when you were talking in public about Full Surrogacy Now, you found yourself maybe softening the message of family abolition in terms of “expanding kinship.” Would you say that is something that other feminists who were talking about family abolition had done in the past? I was wondering if you just might talk about why you felt, at that point, that you needed to soften the message of abolition? And then, what’s making you feel like that wasn’t right or enough?

SL: Yeah. Thanks. OK. I think there are several slightly distinct things in that question, which is a great question. So, I would just say briefly that [when I wrote FSN] I didn’t quite recognize the extent to which family abolitionism was … unheard-of. I mean, I knew that it had been largely forgotten, because there has generally been an active forgetting and un-remembering of what took place in the ’80s, by which I mean a lot of different liberatory projects. This willful amnesia made that term [“family abolition”] disappear completely from the collective vocabulary. But I didn’t quite realize the extent to which that was the case. So I used “family abolitionism” almost as a tacit background assumption of this [first] book, which was about gestating and the labor of pregnancy. I really found that I had to contend with way more surprise than I had bargained for! Perhaps I should have expected it. But in my defense I was a little bit isolated in the research process, my PhD, which led into Full Surrogacy Now. It’s nice to actually be in conversation with people. I now am [in conversation with people] on these topics, but at that point in time I wasn’t. So… that’s one very pragmatic circumstantial comment to answer you!

But I would also say that there were some among the feminists I talk about in my new little pamphlet, feminists who were in the milieu of the 1967-1975 Women’s Liberation efflorescence, for example, in the United States, who very purposively decided to walk the [family abolition] agenda back. Kathi Weeks uses that phrase: “walking it back.” Kathi Weeks has a really great essay, actually, about how abolition of the family was the “infamous proposal of the feminists.” Which is a joke about it being the “infamous proposal of the communists” in the Communist Manifesto. What she’s saying is that family abolition was [also] very much also the high point of women’s liberationist and gay liberationist ambition. But in the late 70s and throughout the 80s, feminists such as Gloria Steinem simply denied that this was the case. They just adopted a stance of erasure and denialism about it. “That didn’t happen. We did not want to abolish the family.” That tactical decision was made by all the prominent liberal feminists, really, who might have been fine with that discourse at the peak of the New Left, but in its aftermath were determined to strategically ingratiate themselves to the capitalist establishment and the state. So, in the the 80s, they start saying “No, no, those people, if they even existed, they were crazy. We never said that. Maybe one or two people did, maybe Shulamith Firestone did, maybe. But barely anybody.” Which is a lie! It’s simply a pragmatic decision that liberal feminism made because liberal feminism is, in my opinion, an enemy feminism and very much a part of capitalist hegemony.

Now a quite different response to your question is this. I talk about this in the new book. It’s the question of the whole queer-feminist ecosystem – which is very much not Gloria Steinem – but rather a whole ecology of comrades who celebrate, in many ways very rightly, the emancipatory effects of survival practices on the margins of private property and bourgeois familism. I’m talking about uplifting queer Black mothers or mother-ers, queer Black mothering practices, indigenous care practices that people have managed to hold on to, wisps, remnants, ancient indigenous ritual or kin-making ethics, little vestiges of things that predate the imposition of the colonial gender binary and the bourgeois private nuclear household, or practices which were innovated under conditions of captivity, for example, under slavery in the United States. Those sorts of practices get called “expanded kinship” or “queer kinship.” And that was what, in Full Surrogacy Now, I was often alluding to when I was talking about “full surrogacy” or “gestational communism.” The scholarship surrounding this “expanded kinship” field in feminism includes really important classic books like All Our Kin by Carol Stack, which is an ethnography of Black kin-making in the “projects.” It’s one of the key texts of this whole field, and in Full Surrogacy Now, I was gesturing towards it. And it was reasonable to read me as saying, “Well, that stuff is, kind of, family abolition.”

I didn’t really say that outright, but it was pretty much implied that I wanted to simply affirm the celebrating of those forms of expanded kinship and survival. Something in there wasn’t quite clear. I hadn’t quite finished the thought. I hadn’t insisted either way, whether or not, indeed, those forms are the same thing as family abolitionism, or simply adjacent to it, or whatever. Now, remember that, in Full Surrogacy Now, I was talking about the untenability of the concept of “surrogacy” outside of a system of proprietary parenthood. I was making the point that “surrogates” are everywhere and nowhere at the same time in the capitalist family model. There are shadowy figures, cut out of the family photo, who are really quite fundamental to the maintenance of this supposedly autonomous, self-managing unit, the family. I talked about how there is a dystopian character to that, and at the same time, potentially, a utopian horizon that could be envisioned by saying, “Full surrogacy now. What if we became capable of acting as though we were all reciprocally and equally, on an equal basis, the makers of one another. Rather than having our reciprocal care segregated along the basis of class and coloniality?” I talked about broadly having a family abolitionist commitment, undergirding that, and then I also talked about the contradictory-ness or the illusory-ness of the family in the present. In the sense that these surrogates are always there, even though the definition of the family excludes them.

But those are two quite complicated things to hold and think together. So… I hadn’t quite finished the thought is the completely honest answer, Scott. Part of the reason I became motivated to write a follow up – which, to be transparent, is something I was asked to do! – was to clarify that aspect. I was asked to write a follow up explaining what family abolition means, and the project was “sold” to me as a pamphlet, which wouldn’t take me long to write (and *cough* it was also paid at the level of a pamphlet rather than a book). But happily, I was sufficiently backed up, at this point, by other family abolitionists from whom I have learned so much. The more courageous character, I guess you called it, the ‘full throttle’ aspect, comes simply from being less isolated.

TFSR: Yeah, and that’s a lesson perhaps of family abolition too. Yeah. If I was going to reduce Full Surrogacy to a couple moves, one of the things that I take away from that is that there’s this deconstructive move, to be like, “we have this idea of the family, but it’s not really how things are working, and if we actually look at the way things do work, we learn that the family structure is in itself insufficient.” You use the the example of paid surrogacy to show first that gestation is a form of labor and one that has the stratifications of class and race. And then in a move that I feel is similar to what Federici does in “Wages Against Housework”: if we can acknowledge this as work, then we can refuse to do it under these conditions. That’s helpful because, with family abolition – I’ll speak for myself – I have as my own experience a visceral response to family abolitionism, which is, like, “Yes.” I think also people have the visceral response of, “No”! But I hear the term “family abolition,” and I’m like, “I hate the family,” like André Gide said. I experienced it as this suffocating space, even if I love the people in my family, and care for them, too. The family structure itself felt like that. So, I have that response.

But then, it’s really hard, I think, in conversation with people to go from, like, “Well, you know, the family sucks,” especially if they have different experiences [than mine], to this more liberatory horizon of like, “What would it look like to do something different?” To make that into a question, I’m wondering how do you connect to those differing responses, which are often so visceral, of yes or no? To theorize it, or even make it seem more practical, beyond pointing out the contradiction – that we currently aren’t actually operating under the nuclear family. Everything that everyone does is bolstered by all these other things. If you have thoughts about that. Just in conversations with people, how do you approach those reactions?

SL: Yeah, it’s interesting to me, ongoingly, how people whose experience is actually forced into unusual levels of dependence on family (so, for example, someone who is classified as having some kind of disability and who has options that are very reduced, artificially, by this world, to, like, institutionalization or kinship-based care, for example) … how people in that situation might have a particularly clear understanding of how that constraint, those two options, the reduction of options to those two things, is pretty dreadful. How they are well-placed to understand that it perhaps doesn’t have to be that way. So you would imagine. But perhaps there’s instead a defensive psychological response of, like, “Well, statistics show that people in my position get maltreated at worse rates in the institutionalization setting as compared to the kinship care setting.” Which becomes a defense of the family. Even though you might then also ask the follow-up question, like, “What are those stats on each side? Is the difference significant? Are we trying to look at the lesser of two evils here? Or what is this framework that we’re operating within, what is the concept of the possible?” Sometimes I find that there’s quite a visceral reaction of like, “How can you attack the family?!” from people who are in fact, in a situation that you could almost call blackmail. Being blackmailed into support for the family because of acute dependency on the family.

All of us, however, are dependent, to some extent, on the family. Even those of us who are in unusual situations vis-à-vis the (biological or legal or juridically acknowledged) family, even those of us with few kin, or who live in dormitories, say, or in otherwise unusual, perhaps creatively different, situations, are still impacted in some way by the world of normative, narrative, romanticization of family.

The very language we speak is saturated by metaphors of blood and reproductivity: they are our containers for questions of self, legacy, and immortality, for our ideas about ancestors, genes, descendants. And indeed the aspiration of a work society is this: to work your entire life for the sake of someone (or someones) who becomes, essentially, an extension of you. I insist very much in this little pamphlet that work and family are 100% inextricable. The regime of work is the regime of family, at least right now.

I confess I don’t know if there’s a conceivable other way in which capitalism could organize itself and work. Society could perhaps organize its reproduction, maybe, in an even worse way. Maybe there are worse things than the family. I’m completely open to that. You can see, for example, that there are dystopian warehousing and dormitory style situations for reproducing the bodies of workers. Amazon warehouses in Czechia, for example. (I don’t know. That’s just a random example, because my friend was organizing there with workers who are literally warehoused in dormitories.)

But there are people who might find it particularly hard to imagine a utopian end to the family, rather than a dystopian one, precisely because of their vantage point. So, since you asked me about how I deal with the emotional reactions, I do try and see where someone is coming from, materially. For instance, it is really important to me to stress, over and over again, that the family really does keep many of my comrades alive. It keeps us alive!! It’s the one naturalized care structure in our society. It is bound up, substantially, with practices of resistance to the state in racialized or undocumented communities. The family is almost ubiquitously celebrated and romanticized in immigrant communities. There are basically no ethnic subcommunity in this nation-state where there isn’t an intense cult of the family. Family values come with a certain proud, almost micro-nationalist flavor, which slots easily into the wider patriotic-nationalist aspiration of citizenship. Oftentimes, non-white family values might feel like a different thing compared to the overarching hegemonic cult of the white bourgeois family, by which I mean, say, the image of the president’s family, the image of ultimate property owning, cis-heteronormative productivity-reproductivity. I’m just not convinced it really is different.

If you ask people about their associations with the family in culture and literature, you can sometimes find that people have all these quasi-nihilistic associations, like The Simpsons. All these darkly or lightly ironizing takes on the disappointment of nuclear heterodomestic life. You can sometimes get people quite far along towards abolition, simply by exploring this. People often resist the phrase, feeling at least initially resistant to the phrase: ‘abolish the family.’ But you can sometimes show people that there’s an anti-utopianism baked into the satirical vibe of the way we talk about the family. The way we roll our eyes and go, “You know, Thanksgiving.” Right now on social media… (Sidebar: I’m maybe leaving social media? I’m sure many of our common friends and comrades were on this list of anti-fascists and have now deactivated.) But I still noticed the overarching tone of popular discourse about Thanksgiving [on Twitter] was a series of jokes about escaping from the family dinner table, right? There’s this joke about having red eyes when you come back in the house, because you went out, to “go for a walk,” to get stoned, to get away, to escape. So there’s this collective open secret of how much it sucks to hang out with your family. Even if it’s ambivalent. It’s an ambivalent feeling. And nevertheless, right? And nevertheless. And nevertheless.

I think that satirical tone is what makes it all a question of relatable-ness and nothing more. That’s what prevents us from having a conversation about, “hang on a minute…. What if the world was organized completely differently?” There’s something that needs to be addressed about that initial affective reaction, as you say. And you brought up André Gide saying “familles, je vous hais” (“I hate you, families!”) which, I think, a lot of queer people feel. And the straight mainstream doesn’t appreciate the extent to which that feeling is a materially, structurally produced affect/experience for so, so many of us. There is a total crisis, an epidemic of dispossession: millions of refugees from the nuclear family are produced, still today, in this era of LGBT acceptance and mainstreamization and homonationalism and homonormativity. There are still ultimately huge populations of dispossessed rejected queer youth, whose relation to the family is ultimately going to justifiably be one of resentment, bitterness, and hatred.

I think you can also move beyond the initial reaction to talk simply about what you actually want for the people in your family, if you love them. And you might find that those things you want for those people is, actually, family abolition. That maybe sounds kind of glib, but I find that if you focus on the love that people often do feel for the people who juridically, legally, or biologically are their family right now, you can often actually bring them around (almost paradoxically), that way, to the political project of creating a world in which the care that all those individuals receive is not dependent on this infrastructure of organized scarcity. Where the ties between people are ultimately predicated on a kind of reciprocal blackmail. Where there are ultimately no other alternatives, yet that is somehow supposed to be romantic.

I really mean it when I say, “if you love your family, you want family abolition for them.” We can unpack that more. But I think I can work with both the very pro and the very anti kneejerk responses.

TFSR: Yeah, that actually makes a lot of sense. For some reason right now, I’m coming with personal reactions to this. And this is one of the ways that you define what love might mean in the book: wanting freedom for your loved ones, wanting autonomy for them, the kind of autonomy that doesn’t seem to exist within the family structure. And the desire for that: that, in itself, is a liberatory desire. That really makes sense to me.

But also, I can imagine the fear, right? You were saying that under the structure of capitalism, which works through the nuclear family as the cell of its reproduction, the family also provides us with the the meaning of our lives – it provides that what we are all working for is the family, or our children, or whatever. So, stepping outside of that structure is daunting. Because then you have to find some other reason to be living. You lose that alibi, and have to face [the existential void]. I like that you brought up work abolition, too. Because then, you have to face the question of what you’re working for. Who you’re working for, maybe, but in a different way.

Maybe we should, at this point, talk a little bit about what we even mean by the family, because it could mean so many different things. When we’re saying “abolish the family” what exactly are we talking about? And what is included within that abolition? And what might not be included in that?

SL: Yeah, absolutely. I think people find this quite surprising if they’ve not thought about it before. But the definition I propose for the family is this: the family is the the name we have for the fact that care is privatized in our society. Or: the family is the form that the privatization of care takes in a class society.

Concretely, though, let’s be clear: I am talking about the capitalist family, not the feudal one, because that’s the one that we’re dealing with today. It’s relatively new! Under feudalism, before capitalism, care started to be privatized in households, which had previously been (the Latin word for servant is famulus) “collections of servants and slaves” (that’s where the etymological root of family comes from). There was no notion of love in the ideology of family whatsoever. The institution of marriage wasn’t an institution with a love-narrative until very recently in our history. It was just a property institution. We brought up (Wages for Housework) Silvia Federici just now. Her account [in Caliban and the Witch] of the way that care was privatized and enclosed inside domestic space during the Enclosures, in the context of the witch hunts, narrates the starting-point of the family in the sense I’m mainly talking about. I do think there’s a pre-capitalist family, i.e., a feudal family (which also involves privatization of care). But I think the family was perfected under capitalism.

What I really focus on, as I’ve mentioned twice now, is this question of the privatization of care. If people aren’t used to thinking like that, it’s precisely because our needs for care are unconsciously almost always, at this point, directed towards kinship and the private sphere. Our needs are met almost exclusively there. What I mean by this includes the scenario where you get an Instacart shopper to do your groceries, or a TaskRabbit to clean your kitchen, or an au pair to look after your kid, or whatever: that’s all privatized care. The social reproduction picture has changed quite a lot under neoliberalism.

Back in 1972, the Wages for Housework Committee that you were talking about was trying to make visible the labor that was done, often exclusively by one housewife, in the domestic sphere. But of course, from the point of view of the overwhelmingly racialized, feminized people who already did household labor for a wage in the homes of wealthier, overwhelmingly white women, the slogan should probably have been “Wages for ALL housework.” Fifty years later, now, there’s a creative fragmentation and dismemberment of all of the tasks that need to go on within a private household. It’s much more complicated than that situation was back then (which which was already, as we’ve seen, bisected by class and race). Today, you can have all kinds of tasks outsourced. At the same time, the basic dynamic of privatization remains. The care that we have can be purchased in or hired out, but the unit responsible for meeting our needs is this anti-social, anti-commons, private realm.

What it would mean to have our needs met in the common or public realm would be, e.g., if you could imagine no longer being obliged to take care of your hunger via you or your partner’s cooking, or your mom’s, in a private kitchen, or having to buy food or purchase private dining. Instead, you would always have the option of having that need met in a central canteen or eating-place, where food was just provided all the time. Or: if you had a need for radical intimacy, perhaps we could imagine not always meeting that need in a little team of designated people under whose roof we usually want to live. It’s fun to live with people, obviously; it’s not like cohabitation is something that anyone would want to proscribe or take away (on the contrary, we probably want to find ways to expand it, while preserving forms of voluntary seclusion). But this is a vision about the sphere of the public, the sphere of the commons, as the center of society, which necessarily means that people are not all working because of their need to survive. In this vision, you can go and get your hygiene and therapeutic needs met, you can mend stuff collectively (e.g., your clothes), swap things, eat, relax, all in the common sphere.

Think about the needs that you get met in the private realm of your household, and imagine the infrastructures that would have to be in place for you not to even necessarily think of going straight home to address them! In the past, laundries (and I’m not necessarily saying this is cool and romantic) would be big central operations where women did the laundry for a whole neighborhood or village together. Obviously: why is it just women doing it? That’s ridiculous. But at the same time, it’s quite an efficient way of organizing some very hard work. And we do want to think about things like efficiency if we are interested in anti-work, which is a horizon of minimization of the alienated work tasks that all of us carry on our backs.

Antiwork is not just elimination and automation of work, but also redistribution and changing the qualitative character of things through that redistribution. It’s not just a quantity thing. It’s a quality thing. Or, rather, at a certain point, diminution of work’s quantity collapses the distinction between quantity and quality: work becomes nonwork. Maybe it doesn’t really feel like work to look after a one-year-old for two hours every other day. But it is work if you have to do it for 20 hours a day every single day. That’s the kind of distinction I’m talking about.

TFSR: That’s really helpful. I was thinking one of the things you say in the book that really struck me. You quote Margaret Thatcher’s really famous claim that “there’s no such thing as society,” only families and individuals. And from that claim, you make this claim of your own: that that means that family is an anti-social institution. At first that would seem not right, because, as you said, we have this idea of family as where we get our connections, or where we know we can connect with people, perhaps. But I think within that phrase, there’s something really interesting, especially thinking about ideas of social war.

I wonder if you might unpack that idea about about family as anti-social a little bit, which I guess would just mean expanding on what you were saying just a minute ago?

SL: Yeah. Well, I’d love to take credit, but it’s really Michèle Barrett and Mary McIntosh’s idea, as expressed in their title, The Anti-Social Family. I think they wrote this in 1982, 1984, I can’t remember right now. But in any case, yes, they are in this Thatcherite moment in the United Kingdom, and they are two Marxist-feminists who are refusing to go along with the generalized feminist strategy I mentioned earlier, of pretending that family abolition was never dreamed of by anyone (apart from maybe some really crazy people). And Barrett and McIntosh are holding aloft the promise, the need for family abolition (we could also say: the orthodox-marxist imperative – ha – but obviously it’s not as though marxists ever really took that part of the Communist Manifesto seriously or honored it, but that’s another story…).

But yes, they say this in their book, The Anti-Social Family. As I read it, basically, Margaret Thatcher says, “There’s no such thing as society. There’s only individual men and women and families,” and they say, in reply: “Yeah, exactly, because of the last part, the first part is true.” The fact of the family is what turns all of human life indoors into the domestic realm for private satisfaction. And so, the social is kind of what happens on the opposite end of that impulse: it’s when we cease to turn inward and meet one another in the commons.

The sphere of the social is starved, systematically and structurally, by the family. Because the family is not just the narrative and the ideology, but also the material means for telling us that all the good feelings that we require, and all the very basic functions that we require, to be able to get up in the morning, are provided in the private nuclear household. They cannot be generated together outside of that unit.

People don’t actually love and cherish the competitiveness of the family, the chauvinism of “keeping up with the Joneses,” the generalized us-and-them mentality this all generates, which is a rat-race mentality (pure survival, working for your entire life, etc). People widely recognize that it is unbearable. Indeed, during the Big Quit or Great Resignation, which we were talking about a lot last year, people did start to reach a certain kind of tipping-point where they were saying, “well, actually, fuck this!” But the thing that makes it very difficult to reach that point is the “doing it for your children” aspect. The “doing it so that your children can have a better life than you had,” or the “doing it for your sick Dad or your sick Mom who doesn’t have enough money to pay for needed medical care.” And so on and so forth.

These are the sorts of reasons why it is the love of another, the love of family, that forces us into these deeply dis-empowered encounters with the labor market as wage slaves.

TFSR: Some of the last things you said was making me think, because you brought up the Great Resignation and I was thinking about COVID and how when the pandemic first hit, it really brought home the insufficiency of the family as a location of care, especially for people that are parenting or like you said, or caring for disabled or ill family members. Because most people still have to work in some way, but then they were also caring. Their structures of care that they need, they relied on school for children, weren’t available.

It’s kind of interesting, I was just thinking about how there’s this huge right-wing reaction to that: trying to force the schools back open, through COVID skepticism, or COVID denialism, which then turned into this whole anti-Critical Race Theory and anti-gay and anti-trans movement directed against public schools. I’m wondering if you have any thoughts about that. Because, again, it’s one of these experiences where COVID hits, and I’m like, “Oh, everyone’s gonna be face to face with the contradictions of the world that we live in, and they’re going to have a fire lit under them to organize things that are better!” But then we have this reactionary and really hateful outcome. I just wonder if you have any thoughts about that? Like why, when faced with the insufficiency of family, and the need for larger care structures, did it take such like a fascist turn?

SL: Yeah. I mean, this is the question I’m asking myself. I think it’s a really important question. I’ve been listening to the Death Panel Podcast, and going on that show a lot, because I think they have such wonderful things to say, both about the concrete policy developments that some of us might (certainly I do) find it quite difficult to follow. They do all that hard policy-crunching work. But they bring alive the political and theoretical ramifications of that stuff from a disability-liberationist perspective.

I’m rereading their [Bea Adler-Bolton and Artie Vierkant’s] book Health Communism right now, actually, to try and find clues as to how, historically, critical utopianists sought to de-privatize care from a perspective of anti-psychiatry and unionized sickness. The Socialist Patients’ Collective (SPK) in Heidelberg in Germany in the 1970s, sought to “turn illness into a weapon.” They wanted to find ways to resist the regime of capitalist health by dreaming of a communist health, a somatic communism that is not about “repairing” yourself and “curing” yourself for the purposes of productivity and work but, on the contrary, persisting for the purposes of becoming ungovernable and unproductive.

Sorry, that’s a bit of an evasion, because I don’t know how exactly the potential that we all felt [during COVID] was lost. I think so many people felt the potential of the moment. For instance, when people were forced to develop “pods”: slightly enlarged little units of temporary non-familiality. Maybe those simply became temporary prostheses to the family. Maybe there was just, say, one another discrete household that you decided to pod with for the purposes of epidemiological prudence, allowing the social-reproductive isolation of one private nuclear family to be attenuated, albeit only slightly, for a period. Pods were on the one hand, allowing people to get a glimpse of what it’s like to slightly open the door. But then, the State of Emergency logic governing all of that, and the ongoing simultaneous retrenchment and turning inward that was going on… Family abolition isn’t something that changes overnight. And unfortunately, COVID ushered in a lot of state involvement in people’s lives. It’s not like the world could be remade on the basis of state law, state discourse, state architecture: things like the apparatus of custody, the apparatus of parental rights, the apparatus of child protection. We’re going to have to figure it out ourselves.

Still, it’s just so interesting how there were two things simultaneously going on: a rebellion against work (which is intrinsically tied to the family) AND an affirmation of the sanctity of family (via the need to stay indoors, to stay the fuck at home). Obviously, some of us anarchist utopians, anticapitalists, feminists, we’re asking, “wait a minute, whose home?!” “In what ways can the private home, organized as private property, the very location where the vast majority of sexual violence and – for women – murder, occurs, be safe? How can you be forcing people into that space under the aegis of safety and wellness? People are going to explode in this pressure cooker situation.” And indeed, people were reporting that domestic violence rates went through the roof. People who were battered or abused, found it especially difficult to flee their partners or their abusive family members because there had been this intensification of the imperative to stay with your own.

This idea of “us and them” is only intensified under a lockdown, on one level. But then at the same time, an antagonistic moral imperative arises, “What about your neighbors? How are we going to make sure everybody’s okay? People are not okay.” So all this mutual aid was simultaneously made necessary, made really obviously necessary. It’s necessary all the time, but COVID raised a little bit more awareness of it.

I just don’t know what the cause of the collapse was. As you’re saying, we saw a gigantic wave of demoralization, at one point. There was so much normalization suddenly going on: a desire for the “normal.” This was very nihilistic, and went hand-in-hand with forgetting the George Floyd uprising. Society decided not to grieve the ongoing fact of death, of mass death. There’s much that is evil flowing from our failure to grieve. I think grieving is the only way you process and integrate the knowledge of this kind of loss. But it’s too challenging, maybe, for most of us to face up to our collective implicatedness in all this brutally unnecessary death. All this death, in all its unnecessariness. We bear a certain collective co-responsibility for the continuation of the world that that produced it, it seems to me. We didn’t start the fire, but if we’re not trying to fight it, we become responsible for it.

Those are just some random thoughts. What about you?

TFSR: Well, I think that that nihilism is really apparent, especially in the right wing reactions that took the opportunity to attack the idea of being taught about racism, or being exposed to queerness and other family structures. Another thing that comes to mind is one of the things about the pandemic that goes along with the anti-social aspect of the family, is that it made us feel unsafe around other people that we weren’t aware of what their exposure risk would be or whatever. So, that was a further isolating element, that I felt even internally as I navigate the pandemic as a chronically ill person. I think about that a lot, about my exposure risks and other people’s willingness to tolerate more risk.

One other thing, I don’t know what you think about this, but a failure on the… whatever we want to call it, but the Left or an anti authoritarian perspective that comes to mind. I’m thinking about this particularly in relation to children. This gets to another point that I want to ask you about: In most left or radical or anti authoritarian spaces, there are still spaces that are segregated adults and children. Usually, there are no children there, maybe in an occasional space, there’ll be some kind of childcare, but children aren’t integrated into it at all. So I feel like in that way, by reproducing the adult and minor hierarchy that we’re limited to in thinking are about the kind of collective care that you call for and Family Abolition.

To tie this historically to what you’re talking about, part of the gay liberation, the historical gay liberation movement of the late ’60s and ’70s, part of what they were calling for or in the idea of family abolition was a liberation, a Youth Liberation too, I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that, where children fit within this idea?

SL: Yeah. Well, Youth Liberation or Children’s Liberation are concepts I feel people have heard of even less than abolition of the family, somehow! Sometimes people have heard of “smash the church, smash the state, smash the family” – those three used to go together in Gay Liberation history. But “children’s liberation,” and the analysis of adult supremacy, those are currently forms of memory cultivated, I think, almost exclusively among anarchists, in North America, at least, as far as I can see. There’s a really great collection that came out from AK Press, by carla bergman, called Trust Kids, which has stories about confronting adult supremacy, in small, voluntarist, small-scale ways, but trying to develop scalable radical democracies intergenerationally.

I do think that, for me, abolition of the family is very much about dehierchalization. I don’t know if I really feel attached to the word “democracy,” but I do feel sure about the need for a truly de-hierarchized space in which we negotiate our need for care. This is also linked to the abolition of work and the productivism of capitalism. Because, under capitalism, elderly people and very young people are positioned, culturally and socially, very much at a disadvantage, because of their relation to the labor market. When capitalism is not yet able to use you for the production of surplus value because you’re too young, or is not anymore able to use you because you’re too old and you’ve been used up, or when you’re never going to be usable because you’ve been classified as disabled (disability can be thought of as a form of inutility, non-usefulness to capital), then you’re being marginalized by capitalism’s ageism and ableism. In that sense, there’s quite a lot of similarity and overlap between Youth Liberation and Disability Liberation. I think some people find that quite startling. They want to hit back and say, “Are you saying that disabled people are like children?” And it’s like: “Do you think that children are not people?”

TFSR: Yeah. Why is that a bad thing?

SL: Yeah. I think the history of experiments in children’s autonomy and equality with adults is quite easily criticized from a Marxist or revolutionary perspective, because they’re so piecemeal. Often it was quite small projects, or, I don’t know, clearly compromised things like fee-paying schools. Things that weren’t necessarily outside of the marketized field of education. For example: There was a school called Summerhill that was quite famous. It was in England. I think it began in the 40’s or even 30’s, I can’t remember. But it became famous in the 60s and ran for a long time. Summerhill was a radical free-school, anti-hierarchical education project. Parents sent children there and paid fees, but while the kids were at Summerhill, there was all this radical pedagogy that was being put in place, with horizontality around decision making and the making of “rules” and agreements, no obligation to go to classes whatsoever. Well, that was the theory. And people spoked holes in it and said, “Well, no, the school master, in a sense, is still a school master. He still pays the taxes on the property.” Lots of people were really keen to poke holes in it from all directions. It was ultimately a private school, right? But it was also an an anti-school. I really found it quite delightful, reading about Summerhill, and reading accounts of some of the big meetings where everyone, young and old, was equal.

It was always asked, “Could the children who came through Summerhill get jobs in the normal world?” And the answer to that was always like, “Yeah, in fact, actually, they were creative individuals who excelled at whatever vocation they decided to study in the end. Because they had only studied what – and when – they wanted to.” Sometimes, apparently, young people would not do classes or schooling for two years at a time before they felt any desire to go to a class, because they were so burned and traumatized from the world of hierarchized schooling they’d left behind. Then one day they would suddenly decide, “No, I do want to learn engineering.” They’re these stories like that. It’s quite inspiring as a tiny little glimpse into what might conceivably be possible in terms of relations between the young and the not-so-young.

With all the caveats I’ve already given, I’m in a way more and more inspired by the youth-led or youth-run collectives and social centers that are talked about in the anthology Trust Kids. Like the Purple Thistle in Vancouver. That social center is the subject of some of carla bergman’s writings. I don’t think it necessarily has the same utopian aspirations that radical pedagogues like A. S. Neill of Summerhill did back in the ’60s and ’70s. But in many ways, it’s more true to its own form, because of its attention to the actual voices and thoughts and writings of actual children, who may or may not actually share the same sorts of Youth or Children’s Liberationist ideas that people like I do!!

You run into these sorts of paradoxes and problems when you try and liberate people – against their will? – at the abstract level of theory. There’s a contribution by carla bergman’s young comrade, or kid, who isn’t really sure about the idea that “children do not belong to anyone.” That is a phrase and a concept that comes up in a poem by Khalil Gibran (“On Children“): “Your children are not your children / They are the sons and the daughters of Life’s longing for itself.” There’s a commentary on that by this teenager. And they aren’t sure it sounds good to them.

The idea that children “don’t belong to anyone but themselves” – and belong to all of us equally as a responsibility – was very popular among Black and so called “Third Worldist liberationists,” or Black and Third World gay and lesbian conferences in the ’70s. There was one caucus that resolved that children must be liberated, not just from the patriarchy, but also from the ownership model of parenthood, full stop. Lesbian parents, for example, would say, “we’re not trying to mimic the proprietary structures of patriarchal parenthood in our own lesbian communities. We want to completely revolutionize the whole concept of parenthood and the private-public distinction all together.”

But then again, you need a model for how children (who have entitlements to very specific forms of care) will be guaranteed this care. There often need to be, especially for the very early years of human life, very stable, very reliable arrangements of care provision. Extremely young people need round-the-clock hands-on care. It’s not at all clear that it has to be the same exact adults delivering this care. Clearly, it can be several. But we have to come up with imaginings for what the model might be.

For that reason, it’s nice to visit speculative fictions, or science fictions, like Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time, where there’s a society called Mattapoisett. I think she wrote this in 1976. She was influenced by Shulamith Firestone’s Dialectic of Sex, with its ambivalent openness to the possibility that some forms of technology could help liberate proletarian gestators – pregnant people – from the burden of necessary compulsory pregnancy if they want to be. That’s very much in a post-capitalist scenario, rather than in the present scenario of techno-patriarchal capitalism, which (Firestone is very clear!) is evil. If something like an artificial womb were to be developed in the present, it would be a nightmare, because it would necessarily be for all the wrong reasons. And indeed, ectogenetic technology is being developed right now by people with very strong pro-life commitments and “fetal personhood” commitments.

But anyway, in this speculative fiction [Woman on the Edge of Time], where working-class gestating pregnant people have thought about their needs for gestationally assistive technology, there’s a communal tank with fetuses. After the fetuses are finished gestating in this “mechanical brooder”, as it’s called, the community does the parenting, according to a three tier system. There’s an expert called a ‘kid binder’, who’s professionally given over to the vocation of looking after kids, because it’s a serious business, it’s a serious art. Then, everybody else is also responsible, all together, for all kids. Then the third level is that every single individual child has three designated parents.

I quite like those concrete proposals, because it gives your mind something to work with. If you know children and can talk to them about what they think about that, I think you can advance a little bit into a less abstract level of Children’s Liberation in 2023.

TFSR: Right. My experience of reading those things is always like, “Oh, my God, that sounds so exciting.” But then, that reaction that you mentioned of like, “Well, I’m not so sure. That’s such a good thing.” That speaks to another desire that could get lost in some of the discussions about wanting to be cared for. And what the distinction is between wanting to be cared for and wanting someone to have power over you. In both of the situations of caring for children or caring for sick or disabled people, that can be transformed into power and control. I mean, that’s what the right wing literally calls it, in terms of parental rights.

But there’s another kind of care, that doesn’t totally destroy your autonomy. I think maybe it’s hard to see that from our perspective now. Right? Maybe even from our desires, because we’re so exhausted of caring for ourselves, that the desire to be cared for might be some kind of totalizing desire, just like an escape, you know?

To phrase that as a question: how do you think family abolition, the idea of family abolition or the movement for it, could transform our understanding of care? Along the lines of Federici saying, “We don’t even know what love is because of being forced to do this for us work.” What is the utopian vision of care that comes from a family abolition perspective?

SL: Yeah, that’s a great question. A part of me is content to tolerate not fully knowing. Simply being up for finding out along the way. Because I think, definitionally, a part of it can’t be known in advance. It would be a little bit like that very moving line of thought that you’re citing or gesturing towards, implies: that we want to find out what it would be like to conduct these same labors in a situation of freedom. All these beautiful moments. Because they can sometimes be beautiful even in the present, where they are stolen from us in large part (not 100% stolen – but a large part of these creativities and affects are being expropriated by capital, out from under our noses). Despite being partially expropriated of them, we sometimes experience some of the nicest, most pleasurable, joyous, liberated feelings, while doing things like teaching a very young person how to speak. Or learning things, back, from them. (What do we learn from one another transgenerationally, or just in general?) It’s the worst and the best of life. In the contemporary organization of maternal drudgery, wiping a child’s nose, as I said earlier, every three minutes, every single day, on your own, with no assistance, that’s a bit of a living hell. But at the same time, the relationship with that same child might be giving you some of the sweetest pleasures of your life.

What we want is to find out what it would be like to not have that whole situation circumscribed by capitalist privatization, such that the isolated intensity of its co-dependency is compulsory (as well as being pretty much all we know). Because, in a weird way, parents are almost, I’m not gonna say equally, but like, similarly dependent on the children who are so totally dependent on them for their care and survival. This is because of the way that your whole identity as a worker would fall apart if you were not the exclusive authority, quasi-exclusive authority and bearer of responsibility over that child’s existence. So, you would have to find out (and this is the kind of curiosity that Federici and her comrades were talking about) – you’d have to find out – what it would be like to love freely. You know, truly freely.

So, care, as you say, in the present is often bound up in power and powerlessness. And I’m not sure that it never intersects with autonomy in a somewhat constraining way. I don’t know. We will find out whether care and autonomy can be interlaced with no friction! I wonder. I think that’s the question! My definition of love is about both care and autonomy. “To love someone is to struggle to strive for their immersion in care,” like maximum abundant care, “at the same time as as having maximum autonomy.” I don’t know the extent to which those two things in the future might rub up against one another.

What I do know is that love is so proprietary in the present. We don’t really want people to be loved by others. Well, I think some of us do. Maybe all of us, even, in our best moments, do. But – because of the enforced scarcity of care, the care crisis of capitalism, the care crisis that is capitalism – we don’t feel it’s safe. We don’t trust ourselves or others to be cared for by many. We don’t trust others, indeed, to be autonomous from from us. I hope and believe, and to an extent I know, that it can be otherwise. I know that the enthusiasm and excitement for those anti-proprietary, anti-possessive modes can spread like wildfire in moments of high intensity struggle, or in moments of mass occupation of a public space where things stay and develop and become creative, become experimental, people live together in moments of insurgency.

That’s when, somehow, the proprietary logic of our emotion, what Alva Gotby calls our “emotional reproduction” of one another and ourselves, along these propertarian lines, is weakened and loosened. Instead we see outbreaks of Red Love, as Alexandra Kollontai called it. Red Plenty, was Mark Fisher’s term. (I’m not sure Mark Fisher was down for our family abolition at all.) I think the emotional level of “red plenty” is the feeling that we are secure in the very contingency of our caring and cared for-ness. Where we don’t need containers like the family, like marriage, like private property, to reassure us that we will be held tomorrow, as well as today.

Indeed, those containers that I just mentioned, family, and all the mechanisms that come along with it (like inheritance and marriage and so on): they are already quite fallible. They do fulfill certain social reproductive functions adequately from capitalism’s point of view. But everyone knows a husband can walk out on you (or worse, maybe, not walk out on you, in some cases?). It is us that the family is not serving. It’s serving the market and the state pretty well.

I keep noticing that the conversation about the crisis of white masculinity in America doesn’t really refer to the ample evidence, the sociology. that shows that men benefit massively from heterosexual marriage. Even with all their complaints, like: “there’s no male breadwinner household anymore” and “women aren’t respecting men anymore.” Whatever narrative is being peddled by Jordan Peterson, basically. The hard evidence is basically that marriage is a great deal for men. It’s a great labor deal for heterosexual men. That’s why they don’t leave marriages. They cheat, but they don’t leave (unless their wife has a life-threatening disease).

TFSR: One of the things that you said that’s really important that comes in feminist and Gay Liberation texts from the ’70s is this idea that the family gives to the worker this mini hierarchy. You get yelled at by your boss at work, but you come home and you get to lord over your wife and children. And then there’s a chain of hierarchy there too, where the husband has power over the wife, or the wife maybe has power over the children. It’s the little laboratory in learning your place. And then also the violent pleasures of having power over someone, too.

I think that’s really an important thing to pull out. That’s how I tried to explain to myself this current movement of, in a moment of devastation and economic precarity for so many people, why there’s a parental rights movement. Why is that the thing? That’s one place where these people are naturalized into having power over someone where they have no power in any other situation perhaps?

SL: Yeah, yeah. That’s fascinating.

Gosh, there’s something I literally thought just a minute before getting on this podcast with you, Scott. Someone shared a snippet of Hannah Arendt, who is a philosopher I’ve always disliked. She’s very, very conservative, in my opinion, anyway. But there was a section of an essay by her that I’d never read, which was her essay opposing desegregation! I didn’t even know this existed! Anyway, she argues that it is too great of an infringement on parental rights, basically, to demand that children go to desegregated schools if their parents don’t want to create a desegregated family culture. She has this fantastically clear and strong statement in favor of the primacy of family: the supremacy of parental authority over the realm of the public. I don’t know if this is actually useful, you may want to cut this from the recording. But I was just thinking about the social crisis that she was writing from within. The tumult of that moment. She’s writing from this moment of racial justice, upheaval, and movement and she’s saying, “The Family is threatened by this, and I choose to uphold the Family.”

I think we need to get braver. I think we need to be able to say, against the right-wing assault against Critical Race Theory: yeah, fine, this does threaten the family. I think there are so many similarities between that “integration” fight and this moment of organized assault on trans children and trans life more generally. Do people have the guts to understand the structure? The way in which the far right is sometimes onto something when it accuses anticapitalists, feminists, leftist of seeking to undermine the sanctity of the Family? Against Arendt, for example, can we insist that that parental rights can go get fucked, when appropriate?

I think the missing part of left discourse is the willingness to say, “Yeah, we do oppose the Family on x and y fronts.” Or even the willingness to merely criticize the family. I’d like us to be able to say: “We do not consider parental rights a supreme value on this terrain.” But we have to be very clear that at the same we oppose the devaluation, dispossession, expropriation and dehumanization of Black parents. There are many groups whose “parental rights” are always already pretty much null and void within the Child Protective Services industry.

Dorothy Roberts has important scholarship on family policing and the very, very white supremacist structure of parenthood as it is defined in settler-colonial law, and in child protection generally. We can, according to her, and I agree, seek to abolish family policing (and to that extent, basically argue almost for the voices of Black parents to count more), while at the same time fighting for family abolition, as a longer term anticapitalist goal. We can defend disenfranchised parents and at the same time struggle for parental rights to be limited or balanced out (relative to the rights of children).

But family abolitionism is full of these slightly tricky-to-think-through contradictions. Because we live in a world in which family is always already a racially bifurcated technology. Which is not to say that Black, or racialized, or immigrant, or queer, or proletarian working class families aren’t part of the privatization of care into private households. As I said, that privatization is the main thing about the family, so, even these alternative forms of household and social reproduction and kinship (which in many ways have skills and experiences that are going to be super useful for family abolitionism) are part of the family regime. It makes no sense to make exceptions for these sorts of marginalized and underserved and underbenefited families. People who benefit the least from the edifice of family values and the regime of familism (as an economic system) should not be used as a reason to shore up the family!

Saying like, “Oh, we don’t mean those families, we just mean, like, the white bourgeois family!” is much safer. People always want me to say that. They want me to specify that, when I say family abolition, I mean the white bourgeois family. But I think if you define the family – as I think it is correct to do – as a mechanism that really affects everybody and is reproduced, wittingly or not, by everyone, then then you really have to be talking about the privatization of care. It is non-bourgeois, non-white, non-settler people who are going to benefit the most from family abolition. In that sense, they deserve it the most. They should not be exceptionalized, or for that matter, romanticized. Because the private nuclear household is not somehow a wonderful thing, just because it happens to be situated in a racialized, proletarianized community. Unfortunately!

TFSR: Yeah, I want to get to the trans stuff, but where you’re leading me is thinking about the selling out of the radical liberationist movements of the women’s movement and gay movement by taking family abolition off the table. Is that another moment of white supremacist consolidation? I’m thinking about gender abolition, for example, or the word gender itself already includes the power structure. I think family maybe does, too, by thinking that family is related to blood and naturalized relationships, it erases other forms of relating to people that happening, but get called the family maybe, wrongly, and reproduces a kind of racialized logic that our belonging is based on blood.

So, what I’m thinking about here, and what I want to ask you about is on the one hand, why was it taken off the table? Do you think it has to do with this racialized logic? On the positive end of this question, how do we relate family abolition to these other kinds of abolitionist movements? Connecting it back to the abolition of slavery, but also police and prison abolition, which is explicitly Black liberationist and fighting against an anti-Black world? Do you have thought on why that was sacrificed in the vision of the movement and how we can make those connections now?

SL: Yeah, it’s really interesting. The collapse of that imaginary at the height of the struggles that proliferated around 1970 is definitely linked to, simply, our material defeat. It’s literally just the epistemic consequences (epistemicide) of the murder, frankly, and repression, that the state successfully carried out. Our people were stomped into the dust. We can’t really state that enough.

You can look at the beginning of the ’70s and the end of the ’70s and simply compare the texts! I found two things that struck me that were amazingly different. From the early ’70s and, then, in contrast, the early ’80s. A text by Pat Parker, who is a Oakland-based Black liberationist radical nurse and “third world” feminist, who has a speech that she gave at an anti-imperialist convergence, and it is all about how white women on the left need to get with the program of family abolition and stop being scared, because capitalism and the state will not fall until women and children explode the cell of the family (i.e. the private nuclear household).

That text [of Pat Parker’s] is amazing, because it puts Black women really squarely at the forefront of that politics [of family abolition], which I personally kind of imagined, like everybody else imagines, until I looked in the archive, was probably most forcefully articulated by the white, Jewish feminist Shulamith Firestone. It’s just not the case. Actually, Black women were saying it way harder, I discovered.

But then 10 years later (and, again, we have to think of all the successful State repression of Black liberationist struggle in the interim), we have Hazel Carby’s very famous and also very well articulated open letter, White Woman Listen!. I think that’s from 1984. And it’s basically about why white feminists’ excessive emphasis on the family as an oppressive structure is harmful to Black women. And she says, “Black feminists do not deny that the family can be a source of oppression, but it’s also, for us, an important site of survival and resistance to the state.” That’s the text that everybody knows. What people don’t know is the previous one, the one 10 years before that. Because as I said, the memory has been erased.

I find it so interesting that essentially, we’re talking about the defeat of Black feminist abolitionism in the widest sense. The abolitionism of the present state of things in its entirety: family, capital, state, criminal justice system, all of it. That intensity was actually voiced by the Black feminist imaginary. Which makes sense given, for example, Hortense Spillers’ analysis of how it is the Black woman who falls out of the symbolic logics of gendered humaneness in the grammar of American life. And it is the Black female social subject who needs to be made a place for. We don’t know what that place would be. She says she doesn’t know whether that place would be called a family anymore. That’s possible.

Tiffany Lethabo King reads Hortense Spillers’ epochal text, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” as potentially family-abolitionist. Tiffany Lethabo King is one of the Black family abolitionist theorists thinking and working today. And she’s not the only one. I quote in my book from Lola Olufemi and Annie Olaloku-Teriba, who are working on “patriarchal motherhood” from a Black radical perspective in the UK right now. I do think maybe it is the defeat of Black power that we must point to, if we want to explain why family abolitionism was no longer thinkable by the end of the ’70s.

TFSR: Thank you so much for this wide ranging discussion. There’s just so much to talk about and it’s such a central and big idea. So I really appreciate you getting into the nitty gritty. For our listeners, if there’s anything you want to say in terms of ways people can support you or follow you, you’re getting off social media, beyond buying the book, which we’ll link to in our notes.

SL: It’s always a massive pleasure to speak with you on The Final Straw, Scott. I learned so much from you. Thank you for prompting me. It’s true, I have a Patreon, Patreon.com/reproutopia. It is my only regular and reliable form of income. It’s really appreciated when people help support my freelance writer life. I’m not sure yet (whether I’ll be on Twitter in the future). I’ll probably be on Mastodon at some point. But yeah, reproutopia is the handle you can find me on. My website is lasophielle.org. You can look at some archives of video and audio on there, and there’s a list of all the essays that I’ve written, which at this point are very, very many (!), on all kinds of concepts, from octopus erotics to the political economy of heterosexuality, and more. But yeah, I look forward to our next conversation on here.

TFSR: Thank you for being willing. And yeah, we’ll link to all that stuff. It’s always a pleasure to talk to you and also really a pleasure to read your work because you are also just a wonderful writer. So I just put that up there too.

SL: Oh, thank you. Thank you very much.