This week, we feature two segments

On The Work of Sex Work with Matilda Bickers

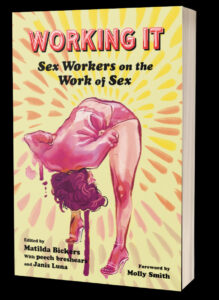

We’re happy to share our recent chat with Matilda Bickers, co-editor and contributor to the recent PM Press collection Working It: Sex Workers on the Work of Sex. For the hour we talk about labor organizing in the erotic industries, Matilda’s past experiences in publishing, hangups around sex work in radical communities and related topics. [ 00:01:00 – 00:43:02]

Harm Reduction and Advocacy

- Green Light Project, Seattle

- Twitter: @GLPsea

- Facebook: @GreenLightProjectSea

- Cashapp: $GreenLightProject or Paypal donations

- Bay Area Worker Support

- website: BayAreaWorkersSupport.org/

- Dancers Resource on Instagram

- StrollPDX (instagram)

- We Too: Essays on Sex Work and Survival anthology

- StripperWeb forum archive

Strip Club Unionization

- Stripper Strike NoHo

- Magic Tavern Dancers

- Instagram @MagicTavernDancers

- Organizing Fundraiser on GoFundMe

Updates from Chiapas

Then, Črna luknja shares an interview with a comrade who’s been living and active in solidarity with the Zapatista communities in Chiapas, so-called Mexico, about increasing violence and fears of civil war. This segment appeared in the June 2023, the 69th episode of BAD News from the A-Radio Network. [ 00:43:02 – 01:01:56[

You can hear some live audio this week starting on July 19th and until July 23rd from the St-Imier anarchist and anti-authoritarian gathering in Switzerland, including audio from the A-Radio Network. More info on that at https://anarchy2023.org/en/radio

Sean Swain’s segment

Following this is Sean Swain’s segment [ 01:01:56 – 01:09:54

. … . ..

Featured Track:

- Patricia’s Moving Picture by The Go! Team from Proof of Youth

. … . ..

Working It Transcription

The Final Straw Radio: Just a quick heads-up: the following conversation does contain references to sexual assault and childhood sexual assault, although there’s not a lot of detail given, but just listener discretion is advised.

Matilda Bickers: My name is Matilda. My pronouns are she/her, and I am a sex worker in Portland, Oregon. I run the outreach project STROLL, and we just published a book, an anthology of sex worker writing and art called Working It.

TFSR: First up, I wonder if you could talk a little bit about the collection and the zine that it grew out of. I’d love to hear about STROLL and also some of your publishing history in the sex work industry.

MB: Sure. So I guess I’ll start with when I was 17, I moved to Portland, Oregon, and I met this group of sex workers. They did a zine called Danzine, their group was called Danzine, and they did all of this stuff. They did street outreach, they’d put together a bad date list, which was they called all of the sex workers in the area and asked if they’d seen any bad clients that month. They lobbied for legislation that was friendlier to sex workers. They were just so amazing. They put on art shows, they put on parties, they put on film festivals, and it really changed my life.

They went dormant when I was 18, and I was just like, “That’s what I want to do for the rest of my life. I want to do what they did”. So I was a sex worker, and it’s 2005, we tried to start a union at one of our clubs, and it didn’t work. Organizing was just really hard, especially without Danzine around to get the word out. And then when I was 28, I think in 2014, I decided to sue my club for misclassification and sexual harassment. With that money, I started STROLL.

I got a grant from Cascade AIDS Project, which is a local AIDS project here, to do street outreach. Between that and the money I had from the lawsuit, I was just like, “Okay, let’s do this.” So a group of friends and I just started STROLL. We wanted to do a monthly zine, we wanted to do street outreach, we really wanted to do everything that Danzine had done because there was nothing like that since they’d closed in 2003/2002. So that’s what we did, and it was awesome for a while. The pandemic really put a cramp in our style, but we’re actually thinking about a new art. We maybe got a grant to do a new art show, the first one in four years. That’s exciting.

But so Working It was the zine that we put out. First it was supposed to be quarterly, but it’s actually really hard to put out a zine on a regular basis, especially with a group like sex workers, where sometimes you don’t have any money and so you have to cancel whatever you’re doing when you do get the chance to see a client to make that money that you need. It was hard to put out on a regular schedule. It became biannual, and then it became annual. And then I hadn’t put out an issue in like six months, and I was not planning on doing another issue when PM was like, “We’re looking for a sex worker anthology. Working It sounds like it might be a good fit. Can you send us some copies?” And I did, and they were like, “Okay, we want to do an anthology”.

That was 2020, so by that point things have changed so radically that I was like, “I don’t really know how much of old Working It is applicable, I’ll try to solicit new material.” So I approached some friends and was like, “Do you want to help me with this project?” and I was lucky they did. Between that and like word of mouth, we just got a bunch of submissions. We went through them, worked with people. Again it was really hard to get submissions on time. The project went from being due in the fall of 2020 to being due in the winter of 2021 and so on. And then we finally got everything in last fall, and the book came out this spring.

TFSR: When you had mentioned the labor conflict at the club — this is a strip club or a dance club —and the issue of classification is about whether or not you were employees versus independent contractors, is that kind of what it comes down to?

MB: Yeah. So basically strip clubs… We used to be employees, and then in the 90s, people were like “Oh, we can make so much more money if we don’t have to pay our workers.” So they were like, “You’re actually independent contractors, and it’s a better deal for you because you get to keep all your tips”, which mostly we did anyway. You paid a fee to work. I don’t think we paid fees to work as employees.

But anyway, it changed, and so much of this situation has gone by in the last 30 years that now people are really convinced that it’s a better deal to not make a flat minimum wage, to not have benefits, and to pay out the ass to the strip club. I was paying like $300-$400 a night sometimes to work, and that’s really common. There’s nights where there’s no customers, and you leave in debt to the club, and the next night you have to hope that you make enough to pay back your debt and have a profit for yourself.

According to the Bureau of Labor Standards, strippers don’t control enough of our work to be considered independent contractors. Like a plumber would be an independent contractor, somebody that you hire for a really specific job that you pay, they come in, they do the work, they go. But that’s not how strippers are. You have a relationship with the club. You don’t really control when you show up for the most part. You don’t control… You have to wear sexy clothes, you have to wear heels of a certain size. And all of the fees that they charge are mostly illegal. You can’t charge someone to come show up late and then to leave early It’s pretty grotesque.

We ended up settling on the sexual harassment. And I mean, this is off topic, but I just really thought that it would go differently because in the dressing room everyone hated what was happening. We hated the sexual harassment, hated paying so much to work, but as soon as the actual lawsuit came out, people were like, “Nope! Nope nope nope nope nope! We love our club. You are crazy. You are so greedy.” I can’t believe… It just did not go how I thought it would. We settled, I got money, I started STROLL. It worked out in the end. It was pretty traumatic for a while there though.

TFSR: Having been a bartender for a while, in terms of a special engagement with employers where you end up… Because of the way labor law in the US was designed from back in the 1930s, home care, agricultural work, food service are these gendered and racialized categories of labor that were thrown under the bus in the 1930s when the National Labor Relations Act was brought about by FDR. And especially in such like a physically grueling job as dancing at a club, I look back on instances in kitchens where I’ve cut myself accidentally or been out sick and had a contract with the employers, the idea of not having that kind of protection where I could take sick days, maybe even get sick pay, because of some contract that I have, or get workers comp in the easy way that it’s available in a lot of workplaces, just seems to add to the stress of that kind of working environment.

MB: It’s really harsh. There’s a lot of clubs in Portland. You don’t need a lot of money to start up, so there’s a lot of divey bars that are just like “We have naked ladies” and the dancers cover the expense of running the club. I worked at one such club that had broken mirrors on stage, and it wasn’t a problem as long as you didn’t get too close to the mirrors. But I tripped one day, and I fell against the mirror and I cut my hand open, and I had to go to the emergency room for stitches. And it’s just like, that happened. I could try to sue the club for workers comp, but I wouldn’t be able to go back there to work. I would be out of work anyway.

So yeah, stuff like that happens. There’s no protection for germs, or there’s no standards for clean stages. So back in 2004-2007, MRSA just kept going around the clubs. Everyone was getting MRSA. And eventually, I think they caught on, and bleach became a standard for cleaning the stage and stuff. But it just took a long time, and a lot of people were out of work because they had giant abscesses on their butts. It sucked.

TFSR: You mentioned one of the important things about the source of Working It and Danzine and Spread [Magazine].. A lot of the importance of these projects is it’s cool for people to be able to share poetry, to share artwork, to share short fiction and such, and I’m sure that these publications offered an opportunity for people to express their artistic side, but also that it provided that forum for people in erotic industries to share tips, to give heads-up about bad practices or gigs, and to just allow people to chew the fat as far as the employment situation went.

In 2018, FOSTA and SESTA were a couple of laws that were passed at the federal level shutting down platforms, or pressuring in shifts of aspects of many surviving services used by people engaged in sex work for this kind of thing, to talk about bad dates, to talk about dangerous clubs or clubs that would rip you off, employers that sort. These websites weren’t necessarily “by sex workers for sex workers” model that these zines were, but people hack what they have to do what they want.

Five years and a pandemic out from the laws passages, I wonder if you could speak a little bit about people’s ability working in the erotic industries to share important info, and you don’t have to name out any specific methods that would get those targeted, but I’d be curious to hear how people have hacked it.

MB: Yeah, it’s been interesting. At first, it was really, really harsh in the first two, three years after because a lot of platforms that people used to advertise and screen clients were shut down, and there just wasn’t anything. People gradually find… they hack what’s out there. There’s new blacklist sites where you can, if you have the app and know people (you have to know people is the thing) you can check who’s a bad client. Then there’s things like The Dancers Resource which rates clubs around the country for dancers from a dancer’s perspective.

There’s stuff out there but now you can’t just Google “bad client list” or “escort reviews.” The stuff that exists now for sex workers, you have to know someone. People starting out in the industry, unless they’re on something like Reddit already — the good forums on Reddit screen, so you have to be a sex worker to join them — so new sex workers are just… I feel like they’re kind of screwed. And that really sucks. Because you need the community, but a lot of people just… you can’t trust people you don’t know. So if they don’t have an established history as a sex worker, they’re kind of out of luck until they build one.

Yeah, it’s harsh. But there are open forums on Reddit that clients can access that are less secure, but you can get generic tips on that. There’s people on Tumblr, on Instagram. It’s out there if you are really dedicated, but it’s not the same. It’s not the same level of ease. You can’t access it with the same level of ease that you used to be able to.

TFSR: As an outcome of those two laws did you notice distinctive changes in the ways, besides the way that people communicated with each other, in how sex work was operating? Or how people were talking about in their distinct cities shifts because of the shutting down to the sort of platforms?

MB: Well, clients got a lot more emboldened, and so did people who make money off of sex workers. Pimp is a really loaded term, and legally, it covers anybody from like a friend that you pay the do security… Anybody who takes money is a pimp or a trafficker, even when the relationship is much more complicated than that. But people who want to have an exploitative relationship with sex workers were really emboldened. I think everyone I know got contacted and was like “Are you running out of clients? I have a client list. I can help you.”

Then clients were like, “There’s more of you than there are of us. We have the money, we have the power.” A lot of people didn’t submit the screening anymore. They were just like, “We don’t have to. You’re desperate. You don’t have advertising forums anymore, so you have to take what you can get”. There was a lot of violence, I think Hacking//Hustling was tracking how many people were reported dead or missing in the months after SESTA. So it was really scary for a long time. And it still sucks. It’s still not great.

TFSR: So you and Melissa Ditmore in the introduction touch on the trafficking framing of anti-prostitution law enforcement in this country, in the USA, that it’s often built around this idea of preserving the innocence of this character of the white cis woman, protecting their innocence for marriage to a white cis man and procreation of white families, that that’s a part of the imaginary that has at times been more or less coded into law.

Conversely, police, laws, courts, and prisons have engaged the bodies of women and other people of color as a threat to the stability of the white nation and the white family. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about white patriarchal imaginary and the discourse of sex trafficking in the US.

MB: Yeah, it’s I think that from the beginning sex trafficking has been really useful for white patriarchy to reinforce it. Everybody’s fears of like “the other,” the dark-skinned rapist “other” man who isn’t a white man, and innocent white womanhood and sexuality, it just funnels so beautifully into that trafficking hysteria. It hasn’t changed that much. It’s really kind of surprising to me how little it’s changed since 1912, which is when I think the Mann Act was passed. I forget.

But this woman just shot a man of color in Texas. He was her Uber driver, and he was taking her to the city that she wanted to go in, but trafficking hysteria on the internet has reached the point where she was like, “Oh my God, he’s kidnapping me!” and she shot and killed him. These white supremacist narratives serve to reinforce the status quo.

You get Cindy McCain looking at a man of color with his daughter, who I think was mixed race, and they were in an airport. Have you heard about this story? They were in an airport, and Cindy McCain was like, “Oh my God, he’s trafficking her!” and he was her father. But this hysteria blinds people to really obvious realities. It makes them so afraid that you can’t talk to them about it. The fear is so intense that somebody would shoot their Uber driver, rather than just be like, he’s probably taking me… Like what are the odds?

It’s so intense to me. If you don’t trust people of color, and you’re like “They’re out to traffic me!” you can’t build solidarity around that. You can’t see what’s actually happening, which is that white supremacy is closing in around us and taking away our autonomy and limiting us and destroying the world, really.

TFSR: I think a thing that that approach has shown over and over again is that it fills a certain psychological need, maybe, that the system imbues in us, in a lot of people in the US, especially white folks, for this sort of danger-narrative. For this fear, this existential fear that we’re already experiencing. Whether it be in the explicitly racialized version or not. Whether it be the idea of the groomer or QAnon trafficking, like farming children for endocrine or whatever, or the groomer narratives around trans folks and queer folks generally. But it doesn’t actually make victims, like actual victims of trafficking, any safer. It actually seems like it endangers them a lot more. You talk about that a little bit in the introduction too and the inactivity or the shifting of focus from where many cases of assault and trafficking actually occur. Can you talk about that a little bit and that shift?

MB: Yeah. Yeah, I mean, agriculture is the number one vehicle for trafficking. By millions of people. It’s just millions more people that are being abused sexually or commercially sexually exploited. And you can be sexually exploited in agriculture. The two aren’t mutually exclusive. But it just doesn’t have the same visceral resonance, I guess, with white people that the trafficking narrative does.

You were talking about the labor laws of the 1930s, and I just found out that actually agricultural workers were deliberately left out of those because most of them were Black, and white people didn’t want to extend protections to Black people. And I was just like, “Oh my God.” And from early on, you just have these structures that are built, and they don’t go away unless you really address them. And people don’t want to address them. It’s too innate in our society for us to want to see them.

But yeah, the majority of people experiencing commercial sexual exploitation are women of color. They’re youths of color, they’re LGBT youth, they’re people in domestic violence situations. They don’t fit the “kidnapped/Taken white girl” narrative. And that is also less appealing, I guess, to the media. We don’t have the same empathy for them that we do for supposedly innocent white people, and that’s how you get people like Cyntoia Brown, who are being sexually exploited as youth, and they defend themselves, and they go to prison. And Cyntoia is lucky, luckier than most because she got like Kim Kardashian on her side, and she got out early. But there’s a lot of people who are still suffering in prisons for defending themselves against their traffickers.

We’re so deliberately closed off to the reality of what’s happening that the Oakland police force in 2016 or so, so many people in the Oakland Police Force were involved in sexually exploiting this young girl that they ran through something like nine police chiefs in two weeks. Every time they got a new one that came out that that person was also involved in sexually exploiting her. That didn’t really make the news that it should have, and not very much changed. Eventually they found a police chief who wasn’t involved in it. She had a lawsuit against the city, and she’s doing okay now.

We don’t want to look at the ways that our system actually enables exploitation, the ways that laws are really set up to enable and further exploitation. Most sexual abuse happens from somebody you know, often happens in the family, and we don’t have any will to look that straight in the eye and address it. There’s no political will to do that, which is really sad to me. It’s really frustrating.

TFSR: So connected to this, I’ve heard people working in the sex industry expressed that there’s a massive failure of leftist, labor and feminist movements, including anarchists, to sufficiently address both the dignity of sex workers as workers, as well as the validity of people’s choices to engage in erotic labor. I’m guessing it’s maybe because as you note in some of your writings that people have trouble deriding an industry and the bad practices within an industry without devaluing the labor that people are forced to get extracted from them in order to make a living. How do you think that non-sex worker leftists more broadly, and anarchists specifically, could be better allies?

MB: I think there just needs to be a lot more conversations, and people need to be a lot more willing to put themselves on the line and do things that are going to be unpopular. Which, in this climate, I totally understand why people don’t want to put themselves out there. You don’t want an internet mob to get mad at you and go after you. But that’s the only way. You have to just take a stand that’s unpopular, which is that sex workers deserve rights and protections.

I feel like there’s a lot of talking points that people could use that don’t get used. You always hear “sex work is not sex trafficking,” and it can be. Any work can be exploited, and sex work is work. Sex work can be exploited. I feel like a better talking point would be like all of this stuff is already illegal. Like child sexual abuse is illegal, rape is illegal. And obviously it doesn’t get addressed, but that is not the problem of sex workers. That’s a cultural problem, and we need to be addressing that.

The problems that people have with the sex industry are just problems that they have with the culture, our culture at large. Sex work is illegal, it’s already illegal. And that’s not changing anything. Like sex work still exists, child sexual abuse still exists, sexual exploitation still exists. You can’t make things that are illegal more illegal. You can increase the punishments, but it doesn’t do anything to address the material realities that lead to these things, which is that we don’t we don’t value women, we don’t value children, we don’t value people of color. We don’t care when their autonomy is infringed upon, and we enable power to reinforce itself.

I feel like those are all pretty good talking points, but they are uncomfortable. Again, it is uncomfortable to admit that most sexual abuse occurs from somebody you know, that things that are illegal still happen. It’s funny, we’re willing to face that with murder. True Crime podcasts are so popular, but when it comes to sex, I don’t know, people have real hang ups about sex. I guess that’s another thing that we need to start talking about more is that like, sex is natural. It happens. I don’t, I don’t know what more to say. But people have problems with it.

TFSR: In your essay “Intimate Labor” in that collection, you talked about the scenario that you experienced where you were working in a club and you were engaging with some of the customers around the possibility of them doing sex work. So sort of like, it seems like pressing boundaries and also being playful and just kind of testing the waters to be like, “Well, you’re engaging with this in a certain way as a consumer, but would you… Is this a thing that you would engage with?” And I think you had some “Would you consider dancing, like doing a private dance for someone in a professional setting?”

I wonder if you could talk a little bit about your thoughts on the trap of moralizing the act of sex as something that is either only sanctioned by the Church or the State, and the choices that people make, without money changing hands, to informally exchange erotic work for shelter or relative safety. And like the distinction that people express towards comparing these acts, where somebody will have sex with someone or do something erotic or make them feel a certain way in exchange for getting a thing that they need, and how people put that on a different sort of field of reality from the drudgery that we put ourselves through on a regular basis for a legal wage.

MB: It’s funny, the people who inspired me to first ask that question were these two women who were like flashing the club. They were like taking their clothes off. And so I was just like, ”You’re doing it for free, how much money would you… to just up it a little bit and actually interact with like our customer?” Yeah, it was like ”A million dollars, and he has to be hot!” I was just like, you were just flashing the club for free. I don’t understand the difference.

Actually, I was just listening to this podcast Just Break Up, and the letter writer today was like, “I’m in a polycule. One of my partners just got the offer to be a sugar baby from this woman. I’m fine with him having sex with her, but I’m not fine with him having sex with her for money.” I was just like, “I don’t understand. Like what?” I would understand if she didn’t want to share him with one more person, but just the act of money made it so different to her that she was in crisis and writing to these strangers on Just Break Up.

Sex has this emotional weight. W’re taught that sex has this emotional weight, but only when it’s exchanged for money. Like you go to bars… Like this one person is in a polycule and has multiple partners and has clearly had some thought about relationships. There’s swingers clubs, there’s all kinds of things. People are willing to have sex for free in all kinds of situations that aren’t even safe. But as soon as you add money, they’re just like, “No.”

I don’t think it’s just because it’s criminalized. I could see that weighing in on some people, but the people that I’ve asked, I don’t think they’re thinking about that. It’s just the act of having sex for money would somehow diminish them in a way that they aren’t willing to deal with. It’s just so weird to me because we spend our lives in work that we hate for the most part. Even if you’re lucky and you get a job that you like, it’s still work. But most people don’t have jobs that are really fulfilling. Most people show up to work, they’re cleaning houses, they’re sitting in front of a computer for eight hours a day. And you can make this amount of money in like three minutes. Like a lap dance is $20. Or if you sell a half hour, that’s like $250. An hour is $500.

It’s kind of reclaiming your time in a way to me, like that’s what I found so appealing about the sex industry. I don’t like working for other people, I don’t like being around other people, I like sitting at home and daydreaming and reading books. It gives you this return on your time that enables you to do that. It enables you to do the things that you want to do that make life meaningful. And people can’t… they can’t get over their emotional hang-up about exchanging sex for money, even if you put it in terms where you’re like, “Yeah, in one hour you could make half of your rent.” That’s time. That’s like, what, two weeks that you would have back to do whatever you want with? But no, there’s just some kind of mental block. I guess if there weren’t that mental block, more people would do it, and then the market would be saturated. So like, personally, I guess I’m grateful for it. But I do think it’s really strange.

I’ve kind of theorized, like I’ve talked to other people, and I know the rates of child sexual abuse. They’re just high. But I do know a lot of people who did deal with child sexual abuse, including myself, and I wonder if that kind of… the fact that we don’t see sex as sacred anymore… like some people do still see it as sacred, but for me, I was just like, “Oh, this is just a thing, this is just an act, and people can make you feel bad about it, but like I’m not gonna let them make me feel bad about this.” For a while I considered myself contaminated, and then I worked through that. And then I was just like it’s just another thing that people do. It’s on par with picking your nose sometimes, like it can be really gross, it can be really awesome, but it’s just the thing that people do. And I can make money, and then I have this money, and I have all this time to do STROLL, to do street outreach, to do the things that give my life meaning.

I’ve been struggling with the fact that I don’t have time to do the things that give my life meaning anymore because I’m trying to transition out of the industry into nursing. Nursing gives my life meaning, but I struggle with the fact that I can’t read any more, like I can’t read books, I have to study constantly. If I do really backbreaking work for minimum wage. I get sexually harassed by patients. There’s a joke among nurses and nursing students that male patients will want you to hold their penis for them while they pee in the urinal. You don’t have to do that. We tell everyone because if you aren’t already told you’ll get conned into it. I was conned into it.

So like, I’m still dealing with people’s sexual abuse, kind of. Like I do regard that as sexual abuse. It’s not heavy, it doesn’t… It’s just really annoying. But I miss having time, and I miss being paid on a rate that I approve of. Yeah, I don’t know what the solution is. I don’t know why people… I guess if it’s just drilled into you from childhood, it’s hard to overcome. But some people overcome it, and some people don’t.

TFSR: I remember back before pandemic began there was a lot of discussion from Red Umbrella Project about pushing for decrim[inalization], where critiques of the.. I don’t know, what you’d call the Nordic model. Similar to the prison system, the Nordic model. Is that still a dialogue that’s going on and being pushed in organizations that you operate in, or has the critique changed since pandemic?

MB: Oh, the Nordic model is deathless. It’s currently rebranded as partial decrim. It’s called partial decrim now because theoretically you’re decriminalizing the seller side but not the purchaser side. But it’s still the Nordic model. It’s still… People still die under it. It’s still stigmatized. They have it in Canada, and rates of murder are still very high among sex workers. Sex workers are still abused.

There’s the case of the woman in Sweden, which also has the Nordic model or Swedish model. She was a sex worker. The sale of sex was legal, but the purchase of it isn’t. But nothing around the sale of sex had been decriminalized. So she was still stigmatized in trying to find an apartment. The child welfare system still discriminated against her and took her kids away. She’d gotten into sex work because she was trying to leave an abusive husband. She did manage to leave him, but they gave custody of her kids to the abusive husband, and she was only allowed to see them on visits with him. On one of the visits with him, he stabbed her and he killed her.

He was obviously not a safe person for children to be around or for her to be around. But because she was a sex worker, the state was like, “No, we’re going to force you into these unsafe situations.” That’s one of my big critiques of the Nordic model is that it doesn’t make sex workers safer. And it doesn’t… it never comes with funding to get you out of sex work. I personally would love to be rescued from sex work. Like I would love for someone to give me money so that I could quit, but there’s never any funding. People email me all the time, and they’re like, “I want to get out of sex work. I’m in a domestic violence relationship,” and I’m like, “There’s nothing, I’m so sorry. There’s nothing.” Like there are some resources for DV [domestically violent] relationships, not enough, but there’s nothing specifically to help you get out of trafficking. Like you can contact the religious organizations and see. Shared Hope International, which is an anti-trafficking organization, is across the river. Sometimes I’ve directed people to them, with the caveat that they’re probably not going to do anything, but you should try. They never do anything. They never are like, “Oh my God, you need rent? You need rent so that you can leave the sex industry? Here’s your rent.”

That’s my biggest critique of the Nordic model is not only that it doesn’t make people safe, but that it never comes with funding, the funding that you need. If you want to eradicate an industry you have to give people options. You have to give them something else to pay their rent, to pay for their child care, to pay for everything. Life costs money under capitalism.

So yes, it’s still around, it’s still a discussion. I have a friend in nursing school, and she’s from Hawaii. And AF3IRM… I don’t know whether you’ve heard of AF3IRM, but they’re a big proponent of the Nordic model in Hawaii. That’s been a conversation lately that she has been sending me little snippets of. Some of their critique is really on point. They talked about how Indigenous women had been affected by colonialism and imperialism, and missing and murdered Indigenous women are missing and murdered because they’re Indigenous. There’s a much higher rate of missing and murdered Indigenous women than there are white women. But the solution to that I don’t think… like they automatically go to “All prostitution is wrong, all prostitution is an extension of imperialism”.

Which, it might be, but you aren’t helping Indigenous women by making it illegal and pushing them further away from resources. Nothing is made better by being made illegal. Like drugs aren’t made safer by being made illegal, alcohol wasn’t made safer by being made illegal. That’s just not how it works. So it’s still out there, still makes me really angry.

TFSR: Coming back to the legislation from five years ago. The assault on sex worker organizing and safety that was FOSTA/SESTA feels like a bellwether for legislation and court decisions at state and federal levels since eroding bodily autonomy around abortion, contraception, education on social struggle, history, gender identity and non-hetero relationships across the country. More plainly said, there’s a huge backlash in the system across the US against any push towards egalitarianism, towards breaking down the patriarchy, the history of racism, all these things. Can you talk about how a robust defense of the rights of people engaging in sex work to better their working conditions and their personal safety dovetails with a defense of sexual and gender autonomy more broadly?

MB: Yeah. I think they’re all issues of bodily autonomy, and they’re all issues around the fact that we need to rethink the way we look at sex and gender and people’s bodily autonomy. It all comes from the same stigma against… I mean, again, misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, and fear and hatred of sex workers, it all stems from the same white supremacist, patriarchal source. If we’re going to combat any one aspect of it, we need to combat all of it. Like you can’t just leave a little patch of weeds when you’re going through because they’ll take over. Like invasive species… Sorry, my metaphor is a little bit convoluted. But like you can’t leave anything behind, otherwise oppression still exists.

I feel like abortion is a really clear parallel with it. A lot of feminists don’t want to see it that way, but it’s what somebody does with their body, and you can’t tell people what to do with their bodies as long as they’re not harming another person. You can’t do that. Even if I have a friend who uses drugs, and that’s her choice, that’s her right. She gets to decide what’s best for her and how she wants to cope with reality. And she knows what’s best for her. A person who’s pregnant, they know what’s best for them, whether they want to carry the child to term or not. A sex worker without very many options… A sex worker knows what options are best. If there was a better economic option, probably they would be doing that.

TFSR: Are there any sites or projects that if someone is considering getting involved in sex work, or are involved in sex work and maybe aren’t aware of, that would help in their circumstances of organizing or of just day-today survival in the so-called USA, any shining lights that you’d specifically point them towards to help?

MB: There’s local projects like Bay Area Workers Support, Green Light Project up in Seattle, Aileen’s which is just outside of Seattle. I think that SWOP Brooklyn closed. There’s not very many. If you Google SWOP [Sex Worker Outreach Project] you can find local SWOP’s that are more active. SWOP USA isn’t very active. And then there’s local projects, but there isn’t a whole lot to direct people to. There’s the Dancers Resource on Instagram, and they have an app if you are looking to get into dancing. I like the sex worker communities on Reddit, even though if you don’t have documentation that you’re a sex worker you’re not going to be able to get into the secure ones. But yeah, there just isn’t a whole lot out there unfortunately.

TFSR: How can people find you online, and as far as other media sources that carry news of sex worker concerns by sex workers are there any others you want to point people to? I guess that kind of covers some of what was in the last question too.

MB: You can find me online, I’m on Instagram @strollpdx, and that’s really it for me. But let’s see, other media of sex workers… I like to We Too which is an another anthology edited by Natalie West. I don’t know of many newsletters or zines anymore. Stripperweb just shut down this year, which was a really good resource for people. I think there’s an archive of it somewhere, but it isn’t the whole site because that would have been impossible to do.

Really, it’s just kind of bleak these days. There’s a lot of community on Instagram and Tiktok and Reddit, and I would just kind of look for sex workers there. Yeah, there was a sex worker festival in San Francisco this year, Sex Worker Art and Film Festival that Bay Area Sex Workers Support did. But not a lot.

TFSR: Are there any questions that I didn’t ask you about that you wanted to speak on?

MB: I always love going off about like the dancers struggle for rights and like Stripper Strike Noho, and a club here in Portland just voted to join the union. So like that kind of stuff.

TFSR: That’s cool. Do you want to talk about that club and what union it is?

MB: Oh, sure. Yeah, there’s a club in Portland that just voted to unionize, and I think they’re going with Actors Equity. I think it’s the same union that Stripper Strike Noho joined. I can’t remember what club the strippers down in LA were organizing at, but here it’s Magic Tavern. I think it’s so exciting.

The pushback was so intense. It’s always so intense. People are so scary and hateful whenever anyone tries to organize. People died in like the ‘30s for trying to organize, and it hasn’t gotten that much better 80 years later. I think they’re so brave, and I love it. I love watching that. I hope that it goes really well for them, and I encourage people to look up the Magic Tavern Dancers on Instagram. I think it’s @magictaverndancers and @stripperstrikenoho. [@equitystrippersnoho]

Zapatista Update Transcription

Crna Luknja: We have on the line a comrade that is now based in Chiapas, Mexico. Thank you for taking your time to make this conversation with us. Let’s start with some basic information about what you do in Chiapas. If we understand correctly, you are engaged in different forms of practical solidarity with the struggle of the Zapatista communities. Can you be more specific about what is it that you do?

Compa: Yeah, sure. I’m working in a media collective. We’re doing audiovisual formation. We started in 1998, when there were like more open state repression on the Zapatista communities. There my collective came in and brought cameras, like video cameras, and started to get information so that all the repression could be captured and could be shown to the world.

From 2014 on the Tercios Compas, the media compas from the Zapatistas, were founded, and so it wasn’t necessary anymore that we would give information if the EZLN [Zapatista National Liberation Army] would do it by themselves. And so now we’re more working with other struggles here in Chiapas. For example, the defense of territory and stuff like that. But yeah, we’re here, and if communities need some help with movie stuff and media we are here to help.

And also we did cover media in the last caravan. That was The South Resists! And yeah, that was our latest thing we did.

CL: Okay, now let’s turn to the recent worrying events in Chiapas. A few days ago, an urgent news reached us about an attack of paramilitary forces against one of the Zapatista autonomous communities. Can you say more about what exactly happened? How serious was the attack? And are these kinds of attacks against particular communities common?

Compa: Yeah. Okay. On May 22nd there was the last attack on the community Moisés Y Gandhi, which is part of the autonomous municipality Lucio Cabañas, which is part of the 10th Caracol Patria Nueva. And yeah, first from one side of the village they started to shoot members of the town at around 4pm, and at 8pm from the other side of the village another part of ORCAO [The Regional Organization of Coffee Growers of Ocosingo] was starting to fire as well. And in this fire, the compa Jorge López Sántis was shot in the chest.

First he was denied medical service, but after urgent action by human rights centers, they got that he went to hospital in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, which is capital of Chiapas, where he still has inadequate medical care. But yeah, his situation as far as I know, he’s still living.

Sadly, it’s not the only case. There’s also aggression on the community Neuvo San Gregorio, which is also part of Caracol 10. One year ago, there was also the displacement of the community Emiliano Zapata and another community where, yeah, you see that violence against communities from the EZLN still happening.

CL: Okay, you mentioned ORCAO. ORCAO is, if we understand correctly, a paramilitary force that is behind also this latest attack. Can you say more about what ORCAO is? What is the agenda that they have, the methods that they use, who are they fighting for? And what is the relation for ORCAO with the Mexican state?

Compa: Yeah, so I think for explaining what ORCAO is I will go back in history. The translation of ORCAO is Regional Organization of Coffee Growers. It was founded in 1988 and firstly at the function of fighting for fair coffee pricing, so that coffee planters could have a good life, which is a good thing, I think. But in the late ‘90s ORCAO started to work with the state and get state funds and positions and power in the government and things like that, in exchange for doing favors for the government. From then on attacks started. In 2002 they attacked the Poblado Javier López and burned the crops of the Zapatistas that are growing their food there.

And it went on. In 2009 there was the attempt of displacing people from Bosque Bonito, which is another community, and also the attempt to attack the Caracol Morelia while there was an international encounter in San Cristóbal. Also in 2011 they attacked Poblado El Paraíso, destroyed 4,500 coffee plants, and there were armed attacks on support bases of the EZLN. In the following years it went on like that. There’s a large register of the attacks against Zapatista communities. And yeah, sadly also this attack on Moisés Y Gandhi is not a new thing. They started in 2019 to do armed attacks on this community.

There’s total impunity of this organization and their attacks and violence. So I think there you can see like the first connection it has with the state, and also that research of the EZLN brought to light that the money the state was planning for a school was used in arms have of big impact.

Maybe for showing a little bit more how the connection between the state and ORCAO is, I think it’s good to look into the program of counterinsurgency that’s still going on. The open attacks by military and the open repression after Los Acuerdos de San Andrés, this open violence changed more to a low intensity war, and parts of that are the paramilitaries like ORCAO or Los Chinchulines or other paramilitary groups. And displacements, which we see in Chiapas a lot, there’s like 17,000 displaced persons in Chiapas.

Also selective assassinations is sadly a thing that we see often. All of this fits very good into an analysis many critical persons have in Mexico, which is that the State, economic forces like big capitalist firms, and also the organized crime are like doing a thing, the three of them. For example, big landowners very often are the government forces and have their own friends with organized crime. So there’s a really, really powerful connection between these and really much corruption.

Often when there’s a capitalist interest, they may say to the governors “Oh, yeah, we can give you money for implementing our project in this part.” And if the people say no, the organized crime or the paramilitary will hit there, and afterwards, yeah, the capitalist interests can enter there. And so I think this connection is a really visible thing.

CL: How does the EZLN and the Zapatista communities deal with these kinds of attacks and other forms of pressure?

Compa: In the last few years I didn’t hear much about how they answer to these attacks. But a little while longer ago, there was for example in La Garrucha, which is like another Caracol, there were attacks, and the EZLN sent men that were not armed with firearms but just with sticks, but there really were many of the military forces of the EZLN, and they went to this community that was attacked. And the people that were armed with firearms, the aggressors, tried to attack but they went to them and said, “So you can try to kill every one of us, but there really are many of us.” In the end they gave their arms, and they went away because there was too much presence of the EZLN.

The Zapatista communities there are also other strategies like from the civil wing. For example, if there’s a land in dispute that other groups want to enter, sometimes members of the EZLN go there and plant and have their present presence there so the aggressors don’t enter.

CL: Maybe let’s now move a little bit sideways and speak more about the general dynamics in Chiapas in the recent period.

Compa: Yeah, that’s a really, really hard thing. The last six years, more or less, the violence in Chiapas increased a lot. That was for one part, I think, because of the elections and because change of power always brings violence with it here. Also in the last years, there is an open dispute between two cartels, like the Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación, which is one really big power, and the Cártel de Sinaloa. Chiapas is the most southern state of Mexico. It is the border with Guatemala, and so this plaza, this region, is very important to traffic drugs. So yeah, these cartels are trying to get the control over it, and to do that a lot of violence is happening.

Also, there are territorial conflicts between communities, and so there are armed groups that are willing to give everything to kill for having territory. It’s really crazy around here, like nearly every day you can hear about assassinations, about armed conflict, about a lot of violence. So sadly, the attacks on the EZLN are not the only thing that’s happening. There’s much more of violence going on.

CL: After the Journey For Life there was practically no official declaration from EZLN except a short statement about the war in Ukraine, and that was already in March 2022, so more than one year ago. At the same time, some sources that are linked to the Zapatistas and the supporters of their struggle, such as the schoolsforchiapas.org website, they openly warn that Chiapas is on the brink of, as they put it, civil war. Can you maybe comment, both on the silence of EZLN in the context of high tensions and also on the civil war concept itself?

Compa: Yeah. So I think for one part, the silence of the EZLN is a thing that already has occurred in history. For example, a thing that came up two months ago is the case of Manuel Gómez Vázquez, which is the supporter of the EZLN who was taken prisoner two and a half years ago. And just now, two months ago, the EZLN made their research and they finished it and so they did that case openly. They mentioned it to human rights organizations.

Also, for example, in 2000, before the EZLN went to Mexico City, there was like a period of three years that they didn’t appear publicly. That’s the thing, they take their decisions, and take the time to make good decisions. Also, there was what compañeros in the Journey For Life were telling us. They took 11 years to plan their insurgency, and this is a big thing to plan. But also other things, I think they take their time to do the right decision. And, yeah, maybe in some time, there will be big changes. Or maybe it’s gonna take a little bit longer and it’s not going to be that big. But I think something’s going to happen, and the EZLN certainly knows when they want to let us know

CL: Okay. And about the civil war?

Compa: Ah yeah, the civil war. I think it was in the comunicado they did about the sequestration, the kidnapping of the two bases de apoyo [core supporters] while there was the Journey for Life. And I think they related to this general normalization of violence in Chiapas and that it’s like a really delicate situation. That would be my understanding of this statement of the brink of civil war.

CL: Yeah, we also remember, yes, that during Journey for Life they stressed a lot the challenges ahead and the difficult situation that for sure is awaiting them on their return. I believe that we are quickly running out of time, so I would ask you for the conclusion, just one that’s a classic question. It’s about what can the supporters of the Zapatista struggle from around the world do? Both about this latest particular incidents of violence, and of course, in general. This, and of course if you would like to add something that hasn’t been mentioned before, please feel free to do so.

Compa: Yeah. So I think, sadly, directly here, there can’t be done much because the people in power have the weapons. And what we can do is show our solidarity because international solidarity often can prevent other things to happen and also can do much pressure. So I think for one part, yesterday there was published a national and international statement against the attacks against the Zapatista communities. Also there’s a convocation for the 8th of June for an international day against the aggressions against the Zapatista communities. And I think that’s basically what people around the world can do, show that they see what’s happening and show that the state can’t do this without people noticing all over the world.

CL: Thank you for the time that you took. Greetings from North Western Balkans to the southeast of Mexico. Bye bye.

Compa: Bye bye.