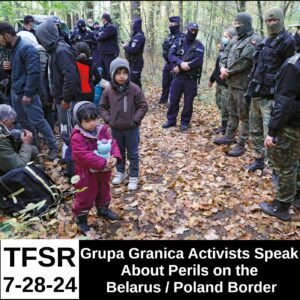

Grupa Granica Activsists Speak About Perils on the Belarus / Poland Border

This week, we’re featuring an interview with Dominika Ożyńska (Egala Association) and Aleksandra Chrzanowska (Association for Legal Intervention [polish: Stowarzyszenie Interwencji Prawnej SIP]), two human rights activists in eastern Poland near the Belarus border who speak about the situation with the migrant route through the Białowieża forest in the midst of increased militarization on both sides of the border through this ancient forest and through the region. Both are active in the umbrella Grupa Granica, or border group, movement supporting people on the move.

In coming weeks we hope to feature more conversations with activists on the ground in this region and elsewhere speaking on similar topics, including locals who’ve seen social and environmental changes as tensions build between the neighboring nation-states and international alliances and how it impacts people seeking asylum and engaging their freedom of movement.

Grupa Granica (Border Group) & Related Links:

- GG Facebook

- GG on X.com

- GG Instagram

- No Borders Team Instagram

- No Borders Team Facebook

- shop without borders / https://www.sklepbezgranic.pl/

. … . ..

Transcription

TFSR: Would you introduce yourselves to the listeners? Whatever name or location that you want to give.

Aleksandra: My name is Aleksandra Chrzanowska. I work for the Association for Legal Intervention, part of the Grupa Granica movement.

Dominika: My name is Dominica Orzynska, and I’m part of the EGALA association, also part of Grupa Granica.

TFSR: Can you talk about Grupa Granica, the Border Group, the umbrella group?

D: Grupa Granica, which translates to Border Group, is a loose collective of different organizations and individuals, activists, or members of the local community who organize together in response to the humanitarian crisis at the Polish-Belarusian border, and they all provide assistance to people on the move who get stuck in the forest here,

TFSR: Can you talk about what the border here looked like, to your knowledge, before 2021 and how it changed and why?

D: Well, I’ve never been here personally, but I think one misconception is that people on the move started crossing in 2021. It’s not true. People used to cross here before, but in 2021 the numbers increased. But when we talk with local communities, they would say that some individual cases happened before too, just it wasn’t a big deal, really.

A: The difference is that, before this humanitarian crisis, this border was very well protected by the Belarusian border guards and army. So it was really very difficult to cross the so-called “green border,” and it happened rarely. But this Polish-Belarusian border was a natural way for asylum seekers from the former Soviet Union. For many, many years, we’ve had quite many people from Chechnya, from Tajikistan, people running away from authoritarian regimes, and they were coming to Poland mainly through the Brest-Terespol border crossing. We also had at that time already some cases of push-backs. At the border crossing, people would ask for asylum, but the border guards wouldn’t let them in, stating that they need a visa to enter, which is actually against the law because the Polish Constitution and the international asylum law says that you don’t need to have any documents, not even passport or ID to enter a safe territory if you ask for asylum. In any other case, you need to have a visa. You need to have a document that gives you the right to enter, but not in the case when you apply for asylum. It’s not precised in the law. It just says that if a foreigner enters the territory of a safe country and is in contact with the border guards of this country and states that they want to apply for asylum, then such an application has to be accepted, and then the migration authorities decide whether these people should be granted international protection or not.

Even before we had quite a lot of cases that people applying for asylum were not accepted at the border crossings. But previously, before this humanitarian crisis that started in the summertime of 2021, we’ve never had so many crossings through the Green border. This changed because that was the idea of the Belarusian regime, the idea of Lukashenko, who stated that he wanted to invade Europe with migrants, and that was in response to the sanctions against the Belarusian regime, the EU sanctions after the stolen presidential elections in Belarus in August 2020. So it started more or less in the spring of ’21 on the Belarusian-Lithuanian border, and then also in Latvia and Poland. Actually, the Lukashenko regime started to invite people mainly from the countries where people run away from anyway. We are talking about people from Afghanistan, from Syria, from Yemen. The information in these countries was spread that it’s easy to obtain Belarusian or Russian visa. We heard about the so-called touristic offices, which opened in these countries, encouraging people to come to Europe. In the beginning, we had really a lot of people here who heard that this was a legal and safe way to Europe. You buy a Belarusian or Russian visa, then you just need to walk for a couple of hours through the forest, and you are in Europe. You are safe. This, of course, wasn’t the case because here on the Polish side, the Polish border guards were stopping these people and whether they asked for asylum or not, from the beginning, they were pushing them back to Belarus. This practice of pushback is an illegal and inhumane practice forbidden in European law, but unfortunately, applied in practice.

TFSR: Based on your conversations with people who have crossed the border, what happens if they decide to turn back and go back into Belarus?

A: They don’t decide to go back to Belarus. When they are stopped on the Polish side they probably get pushed back. When they are here in Poland, they usually want to apply for international protection. But in most cases, they are pushed back to Belarus. Then if they realize that this is a trap, that they don’t want to take this risk anymore, and they want to go back to Minsk in Belarus and then to their countries of origin, in most cases, they are not let in by Belarusian forces. They usually tell us that they hear from Belarusian border guards or soldiers, that once you are here, once you are in this border area, you either manage to go to Poland, or you will die here. We heard a lot about cases when people describe it in a way as if they were punished for the fact that they were not effective in crossing the border and that they were pushed back from Poland back to Belarus. In such cases, they are very severely beaten. Sometimes they are forced to dig their own graves, like a mocked-up execution. And we hear of very different violence, tortures, people are electrocuted, are chased by dogs. We quite often see the wounds after the dog bites. Sometimes we hear also about rapes.

D: The only way that I’ve heard for people to be able to return to Minsk is to pay really big amounts of money, which they usually don’t have at this point, because if they try to cross once and they meet Polish authorities, either Polish or Belarusian authorities, very often we hear testimonies that they take money from people, that they rob them of their belongings. Most often, once they’re back in this part between the Polish fence close to the border, which people call Sistema or a death zone. Once they’re there after several pushbacks, they don’t really have money. This is almost the only way that we hear that they can get out and go to the hospital or to get some shelter is to just pay a bribe again.

TFSR: Somebody told me about a large amount of graves that were found outside of Minsk not that long ago, like 250 graves. I don’t know if this is something that you have heard before. When I asked about this, they explained that this is likely people that got infections, maybe from dog bites, or maybe died of exposure, or became sick because they were drinking water in the swamps because they didn’t have other alternatives. Maybe you can’t comment on that. I can’t point to a news story that talks about it.

D: I have heard this story, but the problem is that we have absolutely no means to verify any of that information with all of the misinformation that’s out there. Because Belarus is just such a tight regime, and most of the people working on the topic of human rights already were forced to flee from Belarus themselves, the Belarusian citizens working in the civil society in the field of human rights, etc. So we don’t really have any means to verify any of such information. It’s quite hard to comment on that.

Recently, there was a report published, and I think so far, we’re talking about roughly 80 confirmed deaths, but we know that the actual number is much higher and we know that most likely, it will never be possible to establish the real number of deaths to people that happened either directly in the areas next to the border or as a result of push-backs and disease or sickness, somewhere around Minsk.

A: From time to time, we hear testimonies from people on the move we meet in the forest that, for example, they were traveling with their family members or with their friends, and some of them died on the way. But they cannot indicate the location. Some of them say that some were on their way, they were passing by and they saw a body, one body or more bodies, both on the Polish and Belarusian sides. It’s absolutely impossible to verify, but I can’t see why would they invent such stories. Because it’s not that we can hear it on an everyday basis. Only from time to time. So it means that if they say so, it means that they either lost somebody or they really saw a dead body. This is one type of testimonies, and sometimes they also tell us that they saw real executions on the Belarusian side, that somebody was beaten to death, or that somebody was in such bad condition because of drinking this dirty water from swarms or from hypothermia, or just because somebody was exhausted. Some people were witnesses of somebody dying or being killed, this is mostly about the Belarussian side, so it’s even more difficult to verify than here.

D: On the Polish side, there were cases where we found the bodies or other people from other organizations did.

A: Maybe one more thing, we are in the primeval forest. It’s huge and it’s really very old, and usually, people who are here need to hide because they are afraid of border guards and soldiers who organize manhunts. If they hide, and they are exhausted and they die, they probably hide in places that are really difficult to access. There are swamps, there are fallen trees, very old fallen trees. If you hide in such a place, and if you die, it’s not a place where anybody would go just like that. If we don’t get information that maybe somebody stayed here or there, there are plenty of places that will never be checked just like that, and nature will just absorb such bodies sooner or later. Probably, you cannot estimate the number of people who died and we will never find out where, when, and how many of them.

D: It’s a huge topic of the deaths because this is one aspect of it that when people are scared and they’re hiding, just as Aleksandra said, it will be impossible to ever find them. But another really sad and horrific side of what’s happening here is that there were at least two cases where people were found dead very close to the houses of the nearby villages. In one case right under the windows of a house. Recently, last year, just on the forest road from the village, it also shows how scared people are. Even in these very extreme conditions, they still were too scared to go and ask for help when they were so close to the houses and people in the village.

TFSR: It sounds like there’s a legal side to offering people help with the process of applying for asylum. Are you aware of activism that people engage in, or human rights accompaniment, or whatever that they do when they find people in the forest, or when they hear that people are coming through the forest? How do people give aid?

A: We mainly provide people on the move with basic humanitarian help. When we get information that there is a person or a group of people somewhere in the forest, we ask for the precise location, and we ask about their individual needs. We always, take with us water, hot tea, hot soup, and some more food, and then we pack the backpack according to what the individual needs clothes, shoes, sometimes sleeping bags, and sometimes raincoats. It depends on the weather conditions as well. If we know that within the group there is somebody who needs medical help, we ask also a paramedic to accompany us. If we don’t have such information, we just take basic medical stuff with us and actually, after three years of the crisis, we can all manage with trench foot or the first stage of hypothermia or water poisoning. We pack the backpacks, we go to the forest, we find the group, and then if people tell us that they want to apply for international protection, we explain to them what it looks like.

We explain to them what is the law. But also we have to tell them that in practice, it might be very difficult because the border guards don’t always follow the law. It happens that even if people declare they want to apply for asylum in our presence, after signing for us the powers of authority to represent them in this procedure, we are witnesses that such a person really declared the will to apply for asylum, it still happens that the border guards push such people back. We have to tell them that we cannot guarantee that this time everything will work as it should. Then we also inform them about what this procedure looks like, and about the risk of being placed in the detention center. If people decide to apply for asylum, we help them to fill in the powers of attorney and a simple declaration, and then we inform border guards, and they come and they take people to the border guards office, and then they should start this asylum procedure, which sometimes takes place and sometimes doesn’t.

TFSR: Somebody explained to me that there are two kinds of facilities that people get brought to, open ones and closed ones. Can you talk about the difference, and what logic you’re aware of as to when people get placed in one versus the other?

A: Normally, if somebody applies for asylum, they shouldn’t be placed in the detention center at all. But here the practice right now is that if somebody travels without a passport or any other ID, they would be placed in a detention center to confirm the identity of such a person. People who don’t have passports are placed in detention centers, and those who apply for asylum and have passports or at least photos of their passports would be rather placed in open facilities. Detention centers are run by border guards, and these facilities are prison-like. You have no right to leave. You have limited access to your phone or to the Internet. You cannot use your own devices. You have a common computer you can use for some time during the day. And I think that the most difficult for people in this situation is this deprivation of liberty because these are people who usually haven’t committed any crime. They just wanted to apply for asylum. That’s why they crossed the border illegally. But illegal border crossing is not a crime, it’s a petty crime, so they shouldn’t be placed in detention only for that.

The other kind of facilities are open centers for asylum seekers run by the Office for Foreigners, and it’s a shelter where you can live, and you have access to food. You can go out or do whatever you want. You just cannot leave it without informing social workers for more than two days, because if you disappear for more than two days, they interpret it in a way that you actually left the country and they stop your asylum procedure.

TFSR: As someone from the US, when I think about Fortress Europe and the border protections, I know that it’s not always Frontex that, for instance, in the Mediterranean crossing or when the Balkan route was a thing, that people were coming into contact with, it was sometimes navies or coast guards for various countries. Why isn’t Frontex operating the border and why is the Polish state doing it?

D: We can say why we think there’s no Frontex…

TFSR: Not to say that Frontex would be great.

D: Exactly.

A: We wouldn’t like Frontex to operate here.

D: Just because the Frontex hasn’t been here so far, it doesn’t mean that it might not show up here very shortly, as every now and then, we hear rumors that the new government might invite Frontex. We always just assumed that the previous government did not actually want anyone interfering with the way they dealt with things at the border. But this was our interpretation of why Frontex wasn’t here because, at the same time, actually, the main headquarters of Frontex is in Warsaw. It is quite ironic that they’re not yet present at the border here. But replacing the Polish authorities here with Frontex or Frontex support would mean just as many violations of human rights as we have now, or more, as we see on other migration routes that you mentioned.

TFSR: The border fence is only a few years old. It doesn’t expand the whole Polish border. Somebody also told me, or maybe I read it, that the British government had helped to pay for part of the border wall installation. It made me think it’s interesting that this is the approach, that they’re not doing it out of some love necessarily for the Polish nation, but to create as many barriers to stop people from coming to the UK, where the GDP is much higher than a lot of other countries in Europe and such. I don’t know if you have any commentary on countries on the periphery of the EU having the responsibility of watching the border being put on those governments and the way that that ends up getting enacted on a person-to-person level with people crossing the border. I know certain Mediterranean border states will pay off the Libyan coast guard to very dangerously pull people back or push people back. It’s not a fully made-up question.

D: Observing the general atmosphere and the tendencies in the rest of Europe with the far right rising, but the European policies on migration, I’m talking about the Pact that was recently introduced, or including these ideas of externalization of migration, it is quite obvious that the Polish government (the previous one and the new one) would not be able to do what they do to people on the move on this border if it wasn’t done with the silent support of the rest of European Union. We’ve seen other European countries speaking out very loudly when it came to the previous government violating women’s rights, for example, or introducing new laws regarding abortion, or some laws regarding climate. We heard the backlash from other European countries and the calls on the Polish government not to turn into one of the regimes, etc. But when the crisis at the Polish-Belarusian borders started in 2021, there was no such strong reaction. Instead, we know that it’s very much in line with the general attitude towards migration in Europe. Of course, the Polish government is responsible for the way they behave. But we need to see changes on a European level in general. Otherwise, nothing could change here.

TFSR: I heard that China and Belarus just ended some military exercises on the other side of the border. There are a lot of people who came from Belarus to escape the Lukashenko regime after the uprisings, and also there’s a lot of tension around the war in Ukraine. This region has had an increase in militarization and I heard of tens of thousands of troops going to be coming here to “secure the border.” People that I’ve talked to in different parts of Poland have been talking about it feeling like war is coming between Poland, or between Europe, or between NATO and some of the countries across the border from here. Can you talk about how you experienced the militarization, further increasing the danger for people on the move in the forest, and also the impacts on the communities that live on the border?

D: This was the main strategy of the previous government: to portray migrants as this tool in Lukashenko’s war against Poland. Naively, we hoped that with the change of government last year at least – I don’t think we were that naive to believe that the situation would improve – but at least we didn’t expect it to deteriorate, and it really did in the recent months. We just see that the new government is really continuing the same methods, the same strategy as the previous one, which is to rule through evoking fear in the society. You’re right. It’s easy to do so because a big part of Polish society is scared and worried because of what’s happening in Ukraine, which is very close, and it’s very easy to portray Belarus and Russia as a huge threat when you see what’s happening in Ukraine.

But this narrative of “hybrid war” that this new government is pushing for, it feels it has nothing to do with the real threat that Polish society might face, and this increased militarization, as well as the fence that was built and is planned to be reinforced now, it’s very obvious that it has nothing to do with the security on this border. Because what we see that it does in practice, is it just increases violence and aggression towards people on the move. I really do not see how violent practices like push-backs, but also beatings, tortures, spraying with tear gas, and basically catching and pushing people back to Belarus, I don’t see how in any way it increases anyone’s safety. Not to mention that, in general, I’m strongly against violating the rights of anybody like this, but it’s almost absurd to talk about security. Security is a basic human right for everyone, so if we want to talk about security at this border and in this region, we have to talk about security for all of the people, including people on the move who are looking for safety and protection here. And it has huge repercussions for them. We’ve seen a big increase in the aggression of Polish authorities against migrants and refugees. Just last week, there was a new regulation introduced in the Parliament and next week, there is the next stage of introducing it, which basically gives complete impunity to Polish authorities to use weapons and shoot at people claiming the right to self-defense with no legal repercussions, meaning no proper, transparent investigation of whether the means used were absolutely necessary. So simplifying it, it just basically gives complete impunity and the right for Polish authorities, military, border guards, and police to shoot people. We really feared that the main victims would be people on the move.

A: If it comes to security, actually, this practice of push-backs is totally against providing security. Some people enter here. [The Polish State] pushes them back. Some of them lose their lives. But the great majority of them, soon or late, maybe after a second or fifth or 15th trial, they finally manage to go through and disappear somewhere. They reach their destination countries without any control, without any registration. If we wanted to have this control and to be aware of who is coming, where they are going, and who they are, we would just need to apply the existing procedures, the asylum procedure, or a return procedure. Applying these procedures gives us the possibility to check these people, to have control. We are not doing this. If we are not doing this and applying push-backs, then we’ll totally lose control. The government talks so much about security, but what they are doing is actually totally the opposite of guaranteeing the country, and the citizens basic security when it comes to migration issues. Because if we talk about security on a large scale, talking about the possible threats from other countries, etc, this is a completely different topic. What’s happening here in the border area as a response to this humanitarian crisis, has nothing in common with these possible war threats. Which we don’t want to deny, it’s just not our expertise. This is not something that doesn’t exist, and people have the right to fear it, but the government’s response has nothing in common with protecting us from a possible war threat.

D: I think we can also be very blunt and clear about this. The government’s response, but also the technique and means by which they create this fear against migrants in society is purely and solely rooted in racism. They basically portray people on the move as the threat, as the tool to destabilize the nation. This is what we hear from people. That these large numbers of people will destabilize Europe. What does it mean? People do not destabilize Europe, people with different skin colors, different origins, different nationalities, religious books, or whatever, they do not necessarily destabilize anything. I can also respect, and I think it’s also important not to undermine the fear in the society against the Belarusian-Russian regime, if we do it, we lose this connection and dialog with the society.

But the perfect example of the fact that it’s not the people that are the problem is the Ukrainian border that was open the first few months of the full-scale invasion, and 2 million people from Ukraine came to Poland, and somehow the country is still standing. Actually, it was a very heartbreaking moment, not only because of what was happening in Ukraine and to the Ukrainian people when the full-scale invasion started but also because it was very clear that the treatment of refugees from Ukraine and refugees from other countries around the world is so different. But Polish society then showed that they were really able to give shelter to everyone, to give transport to everyone, to find food, to organize collectively, to create this network of support. On the government level and the legislation level, even though the response was slow at the beginning, there were also so many new regulations introduced really fast that actually showed that it’s possible to provide the support, financial support to refugees from Ukraine that are not really given to refugees from other countries. These detention centers are a very good example of this, where people from Ukraine crossing the border were not immediately directed to the closed detention centers, obviously, because there is no need to do so. But why then are our people coming through this border directed there? I think we all know that the answer is racism.

TFSR: Could you talk a little bit about the repression of human rights activists on the border? I’ve heard that some people are facing charges for giving aid.

A: Humanitarian help is legal. Actually, we have in Polish law the obligation to help people in a critical situation. If there is somebody who needs help, and we have the means to help them, but we don’t do that, we could be punished. But nevertheless, as those who provide people on the move with humanitarian help, we sometimes face problems and accusations. Since the beginning of the crisis, the border guards and the politicians have done their best to present us as smugglers or as those who collaborate with smugglers, or at least those who help people with their illegal stay. There are different moments. There are some moments when it’s a bit easier for us to work and they just don’t pay attention. But at some points, and it’s usually in the moments when, for some political reasons, they need to show off how effective they are in dealing with this irregular border crossing, so in some moments they really pay more attention, and they try to intimidate us, to make us fear or to tire us. Fortunately, we have only a few very severe cases where people are accused of smuggling people only to provide humanitarian help, but we have quite many smaller cases. As I said, we feel the reason is to intimidate us, to tire us.

D: We’ve had some very absurd cases together. [both laugh]

A: You can talk about it if you want, that would be a long story. Sometimes they invite you for interrogation as a witness, but after five minutes, you start to understand that actually you are heard as a suspect and not as a witness in the case, and they find all possible ways to make you believe that you are helping smugglers or that you are doing something illegal, which is not true, and we know that. But for some of us, psychologically, it’s sometimes difficult to face it, especially if it’s constantly repeating. This is a repression technique to tire people, to intimidate them, to make them believe at the end of the day that maybe there is something wrong with what they are doing.

D: Most of the time they’re absurd, but over time, some of those accusations accumulate, and some people do face more serious risks, and we had cases of the activist bases being raided or people’s houses. Many cases of phone seizures, including mine. My phone was taken by border guards once.

A: When we were interrogated as witnesses, by the way.

D: I went to the border guards’ office to make sure that the procedures regarding one man from Syria who wanted to apply for international protection were followed correctly. Since I had his power of attorney, I went there, and they invited me to one of the rooms saying that this is where his procedures are taking place. When I entered the room, they closed the door behind me, and it was very clear that it was just me and the border guard officer who is who said, “Okay, let’s begin the interrogation.” I was like, “Hold on a second. I don’t remember coming here for interrogation.” Luckily, that time, because we have this amazing lawyer collective that supports us, I actually managed to sneak out of the room because I said I had the right to contact someone. I called them and they were like, “Just say that you want to get out of there. They have to give you an official invite for the interrogation.” I don’t think I even had the exact legal basis to claim that I shouldn’t be there, but with the support of this collective, I felt so empowered that I was like, “No way, I’m leaving now.” And they let me go. But then a week later, they took away my phone and they found a way, but hopefully, they never managed to actually see what was inside. There are many such cases.

There was another thing that we really hoped would change with the old government, and now we hear the new government doing exactly the same thing and again positioning us as a threat to Polish security or collaborators with the Belarusian regime. It’s really tiring and annoying that instead of focusing on proper issues in Poland with the integration of migrants and refugees and all of the things that are actually needed, they focus on this. Sadly, they’re doing this, and it’s sad to see some of the officials who a few years ago were strongly supporting human rights now following the same narrative. It is what it is for now.

TFSR: Could you name some groups and their websites you could think of that people could either learn more about the subject from or offer aid if they’re far away from the border, but maybe have some money that they want to kick in for battery banks or raincoats or whatever?

D: There are quite a few, I think, for your listeners, there is NBT, No Borders Team. Then also there are social media of Grupa Granica where you can also find information on how to donate money, mainly through Sklep bez Granic, which is “shop without borders”, where you can actually choose more or less what are the items that you could donate money to, like a food package or the hygiene kit or psychological help for someone. You can choose and donate the equivalent of that to the shop. But we try to be present during some more alternative events where we try to talk directly to people and spread information about what’s happening at this border. Last year, a lot of activists from Grupa Granica went to different no-border camps in Europe. Unfortunately, I don’t know if we managed to spread it to us, but we do have some volunteers coming from the US to volunteer at our base. This is also great to exchange these experiences. This is also always an option to contact us and actually come and join the efforts.

TFSR: Is there anything that I didn’t ask about that you want to mention, any burning thought that you want folks in the listening audience to hear about?

D: Obviously, we never talk about the positive stories at all, but it’s hard to think of them [laughs]

TFSR: Maybe there’s no time. But any examples of people that you’ve met passing through the forest that are now-

D: I always talk about Zuzia. I think one thing that keeps us going because people find it hard and depressing. There are so many heartbreaking stories. To see people who experience this violence and this unfair, violent treatment is hard. But on the other hand, to see the strength and resilience of people on the move. So many people in this world have to, this is the only way for them to really fight for the future they want, and to see how many people are so strong and brave to go on this journey and cross like this, really gives you the perspective that what we do here is nothing compared to even just crossing this border one time. And we meet amazing people. This is what happens when you let go of the fear of the other, and instead, you’re more open. Of course, we provide help to anyone, regardless of who they are or how they are. But for sure, one amazing side of this is that we get to meet so many incredible, amazing people in the forest.

I remember one story where last year, in the middle of really dangerous swamps, we got the call for intervention from a young woman from Somalia. She was alone, and I remember it took us hours to get to her. We had to cross the river and a really dangerous old swamps where we, me and my friend, got into the mud up to our waist and could barely get out. We were really exhausted. But then, when we finally reached the location, we saw her just holding onto a tree on this little island of soil in the middle of really difficult, horrible swamps. We just both rushed to her through this water and mud and immediately hugged her, even though that’s not something we always do. But she just looked like it was such a dangerous spot that- So we hugged her, and we wanted to at least get her out of the swamp to the dry ground. You can’t leave anyone in that. It’s a clear threat to their life. I don’t think it would be possible for her to get out of there by herself.

We decided to get outside of the swamp, and it was really hard because she spent days in the forest alone. She was dehydrated, she didn’t eat for days. She was exhausted. Her entire body was in pain, you could see that every move, every step hurt her so much. And every step meant falling into the mud until your knee or thigh. Every step required so much strength, and both of us pulling each other, three of us actually pulling each other from the mud. It was a really slow process. I thought that we’re gonna spend ages, we’re never gonna get out of here. It took us two hours to move not even 50 meters. And we were almost losing energy, me and my friend, and then this young Somali girl, she started motivating herself, and this was something really heartwarming. She started talking to herself, like “Okay, you can do it. You’ve come this far. You can you can keep going. Your family always believed in you. You’re the bravest of your siblings. You can do it.” And you could see the strength coming back to her, and she started picking up the pace and walking. I was like “ Okay, there is a chance we will get out of here.” Suddenly, the three of us fell into an even deeper swamp until our waist. I was like “Oh no, we’re all gonna cry again, and the nightmare will start.” I remember I turned back and looked at her standing in the mud up to her waist, and she looked at me and she said, “Oh, my mud!” [everyone laughs]

We started laughing so hard, and a little bit more time, and we got out of the swamp. For me, she’s one of the bravest people I’ve ever met. It’s stories like this that you think it’s all of this is worth it?

TFSR: That’s great. Thanks a lot for having the conversation and the work that you do.

D: Thank you. Thank you for coming here