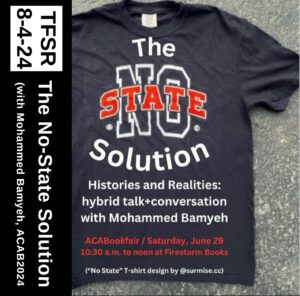

The No-State Solution (with Mohammed Bamyeh, ACAB2024)

This week we’re sharing audio from Dr. Mohammed Bamyeh’s presentation entitled “The No-State Solution” as recorded at the 2024 Another Carolina Anarchist Bookfair in so-called Asheville, NC. Dr. Bamyeh is a Palestinian sociologist and professor at Pitt and the author of multiple books. There is a youtube video of this chat available on the Firestorm Books channel. Shuli Branson’s current podcast is The Breakup Theory and she also authored a zine by the same title as this presentation.

A prior presentation of this title appeared at The Victoria Anarchist Bookfair, a discussion between Dr. Bamyeh and Dr. Uri Gordon. You can find a video or a zine of the dialogue.

Announcements

SCI Fayette hunger strike

According to incarcerated activists in SCI-Fayette in Luzerne Township, Pennsylvania, there are plans to initiate a peaceful hunger strike starting with breakfast on August 5th, 2024, to protest lack of out-of-cell time, locked down for laundry, commissary and evening recreation time during which they can contact family and friends. More on the details in our show notes to support their hunger strike demands.

The brothers at SCI-FAYETTE are planning a peaceful resistance 2 strike all the meals beginning the morning of 8/5/2024 because administration is continuing 2 limit our time out of the cell on the unit, as if we’re in a pandemic. This is the only facility n PADOC that are doing pandemic procedures. Continues to take from us. Creating problems & hostile environment. The men are tired of being locked down for commissary, laundry & now they’re restricting are evening recreation. For most inmates that’s the only time we can contact are family & friends. We want full day room recreation (no cohorts) on every housing unit 7:45-10-30am, 1:15-3:35pm & 5:00pm-8:30pm & more seats on the housing unit 2 accommodate the seating arrangements. We need their help on the outside to call #724-364-2200 & speak up 4 us.

Administration likes to keep matters like this in-house & hope we don’t have any outside support.

Please support us?

To hear about more ongoing and recent prisoner struggles and anti-repression news, check out the monthly column on ItsGoingDown.org entitled In Contempt.

Week of Solidarity with Anarchist Prisoners

August 23-30th is the Week of Solidarity with Anarchist Prisoners. To learn who is being supported, find propaganda and art and how to send your own updates, visit the website solidarity.international

. … . ..

Featured Track:

- Viva Tirado (part 1) by El Chicano from Viva Tirado

. … . ..

Transcription

Firestorm: We’re incredibly excited to be able to host part of the [Another Carolina Anarchist Bookfair] content again this year at Firestorm. We’re also really excited to have Mohammed Bamyeh with us here, joining us at the greatest distance of any speaker. So much appreciation to you, Mohammed, for being willing to do this. I think this is the first time in five years we’ve ever had a speaker who wasn’t present in person. So we’re breaking ground.

Mohammed Bamyeh is a sociology professor at the University of Pittsburgh. He previously served as Chair of the Board of Trustees of the Arab Council for Social Sciences, editor of international sociology reviews, affiliated fellow of EUME in Berlin, and as a senior fellow at the IFK in Vienna. He taught at, among other places, New York University, Georgetown University and the University of Massachusetts. His publications include Lifeworlds of Islam: The Pragmatics of a Religion, Social Sciences in the Arab World: Forms of Presence and Anarchy as Order: The History and Future of Civic Humanity. Of course, we’re very excited today to be talking about the No State Solution.

In order to make this work a little better, we also are pleased to welcome Shuli Branson to the conversation, who will be standing in on behalf of the audience, who are not visible to our virtual audience or Mohammed. Shuli is a queer and trans anarchist writer, translator, community organizer and teacher. Shuli is the author of Practical Anarchism: A Daily Guide, and is currently working on a book about trans-anarcha-feminism. They often contribute to The Final Straw Radio, a weekly anarchist radio show and podcast based here in Asheville. So much appreciation. For folks who are joining virtually, I’m sorry that you can’t see our full audience. We’ve got maybe 60 or 70 people here live. So we’ve got a very full house with folks spilling out onto the deck of the building with an outdoor speaker, in order to hear this conversation. I know it’s going to be an exciting one. Thank you again, Mohammed, and thank you, Shuli, I will pass off to you now.

Shuli Branson: All right. So yeah, I’m going to be here to facilitate, and I’ll just let you take over now, and as you need me to jump in and let me know.

Mohammed Bamyeh: Thank you Shuli. I appreciate the generous introduction. I wish I were able to be with you in person, but we do what we can with the technology that we have at our disposal. I’m happy for this invitation to share with you an idea that is still developing actually. The idea of a no-state solution kind of emerged, or has been talked about occasionally over the years, but with no analysis really behind it. The real thinking about this idea began in a conversation a few months ago and is still developing. Also with the help of audiences like this one. It is, of course, as you know, motivated greatly by the war in Gaza right now. But the idea goes beyond Gaza itself, and also beyond Palestine, and beyond the particular conflict, which provides the empirical material for the idea in general.

I’d like to go through the idea in four or five steps with you today. First, I’d like to talk about why. The first step is to describe why the obvious solutions to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have never worked. Second, I’d like to talk about the social history of Palestinian self-organization and agency. That is how society manufactured the society without the state already. The experience of living without the state is already with us. It’s not something that we need to think of as something that requires new experiences. Then I’d like to spend some time talking about the virtues of the no-state solution itself within the larger scope of Middle Eastern social histories, of which Palestine is part. And then, fourth, I would like to spend some time talking about the failing states as we have them today, at multiple levels, as well as the revolutions against them that are also symptom of their failures and the rejection of the people of those states. Finally, because it was always mentioned when we talk about any anarchist idea: realism. The concept of realism, or what we mean by it, and how to actually approach the whole idea of realism given the kind of realities that we have. So there’s a lot to unpack in 45 minutes or so but it is doable.

First of all, let’s begin with the with obvious solutions. For the last five decades or so, there seemed to be at the official level one kind of “realistic”, so to speak, solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which was the two-state solution. That seemed to be a realistic prospect for a long time, and continues to be talked about, because it was a solution that the international community itself endorsed, that the United Nations was behind, that the United States itself officially endorses, and the European Union. Arab governments are behind it. Many Palestinian organizations have already accepted it, including the news. Before 2006 Hamas itself had actually accepted the two-state solution. For various points in history, a majority of Israeli and Palestinian societies also accepted the two-state solution. So you have a solution that had all the ingredients of success behind it, yet we have never been able to get to it. It seems to be a puzzle as to why.

There are three reasons why we have never gotten to that, and we will never get to that, actually. First is the balance of power is a problem. We have two entities here. One is an Israeli state that is armed to the teeth, that is very powerful, that has unlimited support of the one remaining superpower behind it. It is also relatively wealthy and secure, in spite of the fact that it talks about insecurity all the time, but it is the most secure regime in the entire region. On the other hand, you have a Palestinian population that is dispossessed, that lives under occupation or in diaspora, that is weak, that is unable to—because of its relative weakness, vis-a-vis the Israeli government—is unable to get the absolute minimum that it can get out of this kind of solution.

So you have an equation, right? If we think only about Israel/Palestine, where one partner has all the power and other has none of the power, it means that basically, the powerful party in the equation has no incentive to provide the absolute minimum that the weaker party is able to live with, and the weaker party has no resources to get the absolute minimum that it can live with. So that solution, or that kind of formula, can be changed only when you have a third factor entering to the equation, that fixes that balance. Actually we do not have any force that is willing to enter into that equation. The United States is not going to do it. Neither will the European Union. Neither would their governments. That leads me to the second reason as to why the solution is not going to happen. Namely that the Palestinians themselves are not a priority for any government in the world. Even though there are governments that in principle and in theory support Palestinian rights and support the Palestinian right of determination, these governments are either far away or unwilling to invest the kind of political capital that will be necessary to solve the problem. This is a reality that is verified by history.

We had lots of talk about the two-state solution before, namely, after every crisis, like the crisis we are facing today. We have basically lost diplomatic talk about the two-state solution that emerges, where diplomats, secretaries of state and so on, travel around the world, and say, “A two-state solution. Two-state solution. Yes we have to work on it.” Once the crisis over, all that diplomatic language is forgotten, and we go back to the business as usual before the war. That has happened before and that will happen again after this war. That is, there is a talk about the two-state solution as a way to pacify the Palestinians for a while. Once the war is over, once the crisis is over, we are going back to business as usual. Because state interests have nothing to do with the Palestinians.

The third reason why the no-state solution is not going to work, it has to do with settler colonialism, the fact that Israel is a settler colonial entity right from the beginning, ultimately. I could go on for a long time about that particular point, but it is a program that is based, like most settler colonial experiments, on dispossessing the indigenous population and treating them as a problem as opposed to partners in the land. You see that from beginning of the Zionist project where, for example, if you look at David Ben-Gurion, who is seen as the founder of the State of Israel, in 1915 he migrated to Palestine, and he worked on the Zionist project. He was good with languages. He spoke seven languages. Arabic was not one of them. So the language of 95% of the population of Palestine. When he went there, he did not bother with that. Furthermore, he told his people after 1948 “We have to remember that we are in the Middle East only in a geographic sense, but we belong to a different civilization,” meaning the West ultimately.

So here we have a settler colonial entity that regards the indigenous population—in fact, all the surrounding populations as inferior to them and as people from whom the land would be taken away. That is also true of even of the kibbutz as an institution, which is imagined in the West, basically as an embodiment of socialist, utopian principles. But what’s not known about that: It was, in fact, started as a racial experiment. This is what people don’t know about the kibbutz. The first kibbutz in 1908, was established as a way to exclude Palestinian farm labor from the Jewish farms that were being established in Palestine, to create cohesive Jewish only communities, cohesive Jewish only businesses, a cohesive Jewish only society in Palestine.

That project continues until today. You see it in the form of settlements that are being built in the West Bank, and also previously had been built in Gaza. Of course, these settlements, their costs are enormous in terms of land, in terms of water resources, in terms of expropriating the properties that belong to the indigenous population. For example, Gaza, from 1967 until 2005 was under Israeli occupation, directly. During that time, Gaza had Israeli settlers in it. There were 7,000 Jewish settlers in Gaza and 1.5 million Palestinians. The 7,000 Jewish settlers controlled 45% of the land of Gaza and half of the water resources. So you have 7,000 people, having as much land and as much water as 1.5 million people. This is settler colonialism. That is the character of the settler colonial project that continues to be in full force until today.

So for these reasons, these three reasons, what looks like an obvious state oriented solution that could be put in place will never work. Now, the second line of my discussion is, how do Palestinians respond, or have historically responded to the situation? Because obviously, part of the story is the agency of the indigenous people, ultimately. Now, the Palestinians were expected to disappear after 1948 with time. This is something that John Foster Dulles, the Secretary of State under Eisenhower, predicted back in the ‘50s. He said, “The issue of Palestine, will really cease after one generation.” That when you have a generation of Palestinians born outside of Palestine and have no connection to the land, then the problem would be resolved that way, with time. “We don’t have to do anything about it.” Of course, that did not happen. In fact, we had the opposite happening, and then you had several refugee generations in the meantime, that have even more commitment to Palestine.

How did that happen? There are three sources for this remaking of Palestinian society, all of which happened from below and without a state to speak of. This is really important to keep in mind. First of all, the refugee camps themselves, as a site of generating Palestinian identity. So the refugee camps where many of the refugees lived and continued to live for two decades after 1948. The refugee camps are not recognized encampments. They are supposed to be temporary structures. They do not really have a state law governing them. There are no property lines, for example. But once you have generation after generation living in those informal settlements, obviously some kind of law is going to govern their lives somehow. That law was Palestinian village culture. So the Palestinian village had this culture, these codes of mutual help and solidarity and conflict resolution. All these known, quasi-anarchist, voluntary traditions, migrated with the Palestinians into the refugee camps. So the Palestinian village, with its traditions, became one of the ways of actually making Palestinian life possible. And the old traditions continue to live in the diaspora, especially in the camps in particular.

By the late 60s, there’s a new culture that began to develop itself in the refugee camps, and that is the revolutionary culture. So you have modern organizations, all of which became part of the PLO. Those were organizations that had the character of political parties. They had militias, they had to work across refugee camps. They tended to have a meritocratic culture in the sense that people get assigned position on the basis of their capability, as opposed to social upbringing and so on. You had these two cultures, the traditional kind of village culture and the modern revolutionary culture. Both of them together conspiring to create a modern Palestinian identity. In addition to that, you have a third movement happening globally, in the globalizing diaspora, which is the establishment of a Palestinian civil society outside of Palestine. That is from the associations of cities, the workers unions, women organizations, pharmacists, doctors, etc, all of them organized as syndicates globally. All the syndicates became part of the PLO as well.

Over several decades, Palestinian society that was expected to disappear, recreated itself in diaspora, without the help of any state. That is part of the learning process of how to live without the state, how to create a sense of a strong identity connected to a cause of justice without any state, even though most states expected the Palestinian structures to simply disappear. Now this experience of living without the state—and this is one thing I need to emphasize—is not unique to the Palestinians. If you look at the population in the surrounding area that we call the Middle East, you also see similar experiences—especially from the 90s onward, but even earlier, depending on where you look—that is with the beginning of the neoliberal era. Then neoliberalism begins in a different time depending on where you look. With neoliberalism you have a situation where lots of people in Egypt, or Iraq, or Syria, or Yemen, or what have you, begin to realize that the states that they have tolerated so long are not going to do much for them. You have therefore, lots of people living outside the state, building shanty towns with each other’s help, without permits, without legality, without connection to the electric grid and so on. One house at a time, one family at a time, helping each other. Eventually we have millions of people establishing entirely new cities without permits and without a state license. That has consequences for the revolutions that I’ll talk about in 2011. Namely, you have all kinds of societies in the region, in addition to Palestine, or parallel to Palestine, that are also learning how to live without the state, even though there is a state above them, but it is useless to them, or at least it is their enemy.

Now let me move from this reality to a little bit of history, the historical patterns of social organizations of the area that they call the Middle East. Historically—and by historically, I mean before the modern state, before the colonial period in particular—the free movement of the population across borders was a norm in the entire region. There were technically borders, but they were not policed. People did not take them seriously. Free movement was a norm. That was historically the case because it made it possible for people to adjust to problems of demographic pressures, and also because long distance commerce was the main source of wealth in the region as a whole. As a result of that, you have, especially in the urban areas of the Middle East, (like Damascus, Baghdad, Cairo, etc,) all of them develop a multicultural, rich, interconnected life, where you have several communities living side by side, and none of them really feeling a pressure to build their own state. Nothing depended on a state for those people.

For example, you had Jewish communities, historically large ones, across the Middle East, in Baghdad in particular, throughout Northern Africa and Morocco and Nigeria, in Egypt, in Syria, in Yemen and so on. Not in Palestine. There was a small Jewish community in Palestine as well, but most Jews in Middle East were elsewhere. They never thought about going to Palestine, even though that was the so-called promised land, and there was nothing to prevent them actually from going there. There was actually no need to do that. That was a historical reality. Ethnic identity was not set in stone, even though it did exist. People used the idea of multiple loyalties as the norm, and we’re used to a region that is interconnected, where states—even though they did exist—they did not mean much to the daily life of the people. Even though there was an empire, we call the Ottoman Empire, that presided over the whole thing, most people did not see that empire in their everyday life. That empire itself survived for 600 years precisely because it left people alone. It was actually based on multiple loyalties, with the right of each community within the empire, to rule itself according to this own laws. That’s the reality that began to be disfigured with the creation of modern states throughout the region.

The pattern of social organizations that we have historically, and that continues to be familiar to a lot of people, was the pattern of free movement, mutual solidarity, inter-communal life, together, side by side. No need for a state to impose any rules on them. That is a reality that Europe, after World War Two, began to discover as something that it needed to work through, in order to prevent the Third World War from happening in Europe. We already had that, except that modern colonialism disrupts that and that historical experience. But that has not gone out of memory. When you look at ideologies like pan-Arabism, for example, it was, in fact, not based on nationalism in the traditional European sense, but on people rejecting the artificial division of Europe by outsiders and rejecting those ideas of new borders. So borders basically were not meaningful. As they should be, historically.

In 1948 and after the present Nakba—in the summer of 1948—some Palestinian refugees, peasants in particular, began to try to go back to their fields in time for the harvest. They were shot and killed at the borders of the new Israeli state. That had never happened before. At that time, people began to realize that borders now means something a lot more rigid than they ever did before, and that is a new reality that we continue to live with until today. Now, the reality of this case as we had them today—and this is actually where I want to expand the argument as to why these states actually are failing right now across the board. First of all, we have a clearly dysfunctional region. The Middle East right now has five major wars. More wars than anywhere else in the world. All of them major. In Gaza, of course, where it is genocidal, for example. But also in Syria, also in Yemen, Sudan, Libya. We also have a situation where you have financial collapse in some countries, that is imminent. Lebanon or Egypt, for example. We have all kinds of local hostilities at a smaller level that can break into civil wars as well. Wars, not our own though a lot of them right now, but they’re also frequent in the modern history of the region as well. So clearly, something is not working in the modern structure of the region.

In addition to that, you have states that are based on enormous inequality as part of their structure. For example, you have in the same region, very rich countries right next to very poor countries. So if you look at the region as a whole, the Middle East is the most unequal region in the world right now. Also the most militarized region in the world. The two go hand in hand. Let’s be clear. Vast inequalities, vast investment in a security apparatus. Problems of security compound because ultimately, what happens is that if you treat the population as an enemy with disregard and you call them human animals like the Israeli Minister of Defense called the Palestinians—they’re going to hate you, and they are going to become your enemy and you are going to have a security problem. Then you are going to complain about your security problem, which you yourself generated. So you have the problem of security, because the governing institutions that we have themselves create the kind of insecurity against which they complain. That justifies further investment in the security apparatus, more militarization of society, and the use of force as the first resource.

All these are some sorts of failure of the systems as we have them today. These are the problems that result from the fact that all these states, that we have in the region have been created essentially as imposed structures. We don’t really have anywhere in the region, an organic process of state creation, where a state is actually established because of the will of the people, that comes from the bottom up, or at least is represented by some kind of elite force that translates what it has to public wealth. That never happened. For the most part you have states that have imposed themselves or been imposed by colonial powers against an unwilling population. When that population was too unwilling to accept the new state, you have something like in Israel, where you have an ethnic cleansing, where the population is violently expelled.

Elsewhere in the region it is the same. You don’t have as much in the way of ethnic cleansing— occasionally you do have that but for the most part, you have large populations that regard the state to be their enemy, ultimately. And it is their enemy. It regards much of its population as a threat to it, as a state. So, either we have that condition, where we have large populations being guarded as a threat, or you have an apartheid system like we have in Israel. Israel is imagined often in the West as a democratic state. It actually does advertise itself as a democracy and is talked about as a democracy, but if you look at the entire population that Israel controls between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean, half of that population has democratic rights. Only half. The other half have no rights at all. Which is what we call apartheid. It is a single state. All these populations are governed by a single state. It is not democracy. It is an apartheid condition that, of course, calls itself democracy. South Africa under apartheid was also a democracy. Right? But democracy only for the whites, ultimately. So these two conditions, democratic claims as well as the apartheid system, can live side by side. That is what we have.

Now I want to spend some time talking about an earlier revolutionary period, against the modern states. Then I will move to the modern revolutionary period. I’m not going to go too much into details because of the time, but one thing about states that are imposed on population is that those states sometimes become tolerated by the population that they control, to the extent that they can deliver some goods, to the extent that they promise something like some post-colonial states have done the Global South. Promising development, modernization, sovereignty, rights, etc. When a state appears to be doing these things, then it might be tolerated, even by a population that is hostile to it originally. We did go through that already.

We have, in the Middle East, beginning with the early ’50s, the so-called Free Officers Era, where a number of young officers from the army took control of governments in several countries, including Egypt, then Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Libya and so on. Those few officers tend to be young men, typically not from the old elite, but actually often from marginal social backgrounds, often from rural backgrounds, in fact. They presented themselves as a “man of the people” type and basically had socialist ideas. They invested in the public sector and tried to redistribute wealth more equitably for a while. They invested in women’s rights as well. So for a while, it appeared that, that kind of revolutionary elite, so to speak—that of a modern but also marginal background—would be able to deliver this kind of modern project that would take us into economic modernity, progress, prosperity, rights and so on.

The problem with the system was that they were all dictatorships. There was no accountability and with the entry into the neoliberal era, all those project were abandoned. What used to be the Free Officers Era collapsed completely. As a result, in 2011 we have a new revolutionary era that we enter: the era of the so-called Arab Spring, which, so far we have two iterations of it in 2011 and 2019. All these revolts had a character that we never saw before. That is, all of them happened without guidance by any political party. They did not produce a Free Officers or anything like that. They had no interest in vanguardist leadership. They seemed to be nonchalant about organization or centralized leadership, even though earlier revolutions in the region did have those properties. They had leadership, organization, etc. It is something that I studied quite a bit, because I was interested in why you have what I call this organic anarchism as part of the mentality of those revolts. It seemed to me that there is a history behind that; the history that I just described. Ultimately, that we have tried vanguardism. We have tried the Free Officers. We have tried these dictatorships on the hope that enlightened despotism would work in our benefit. We have already tried all of that and we ended up against the same wall every time. All these systems became corrupt repeatedly. Not only corrupt, but also now genocidal and murderous.

Out of that reality, organic anarchism evolves. You will see it put into action by millions of people who never read any books about anarchy, who do not even know what anarchism means as a concept, and who will not even call themselves anarchist. It is an anarchy that comes out of the earth, out of an experience where you have a hostile authority that is doing nothing for you, and you have to rely on each other to survive. So this is the anarchism that comes out of the necessity for survival, the necessity for mutual assistance, the necessity of mutual help. The necessity of figuring out a way to resolve conflicts peacefully, with your neighbor. That is what the Palestinians have been doing all along, without a state.

That is where we ended up in 2011 and that is where the idea of historical memory emerges in the form of summary judgment on the record of earlier historical revolutions and what we are supposed to be in the current climate. So it seemed to me that the 2011 Arab Spring movements, suggest not simply people wanting to overthrow a regime—which was a mere slogan—but rather people wanted to overthrow the state. That was not, of course, the conscious slogan. That was not the expressed slogan. But if you look at what people were doing, the fact was that they did not actually care about forming a single political party as happened before. If you look at the psychology of the revolution itself, where millions of people, for the first time felt more free than ever—it was during the middle of the revolution. The greatest experience is that precisely at that moment you are not being governed. And that becomes a precious memory for everyone that participated. So we have a reality where—not just in Palestine—people were rejecting the principle of being governed. Not out of an ideological kind of consciousness of anarchism, but out of the historical experience that brought them collectively in that direction.

Now when we talk about the no-state solution in Israel/Palestine, we have of course, to evaluate it on the basis of the solutions that appears to be realistic, or have historically appeared to be realistic, such as the two-state solution—which is not going to work for the reasons that I mentioned at the beginning—or the one-state solution. If these actually happen, fine, I guess. For a while. But they are not really any more realistic then the no-state solution at this point. The problem, of course, that we face right now, is that we have a reality that is completely unacceptable. It is a reality that is created by realism as a perspective, by people wanting to actually think within the bounds of realism—(what we call realism), namely statecraft—that create a diplomatic kind of effort, UN resolutions, etc. State-centered thinking that tends to be called a realistic kind of thinking.

If you look at the Palestinian history, the Palestinian resistance movement, you see that actually, that movement was never realistic. That is, you have a very powerful enemy, so the realistic thing to do, is to surrender. That is the realistic thing to do. But we haven’t done it. We fought against a powerful enemy and against all odds, knowing full well what we are fighting against. The same thing had happened in other revolutions as well. With Khomeini in Iran. I’m not praising Khomeini, but I’m looking at the particular kind of way of avoiding realism as a way of motivating the revolution. Again, he had no prospect of success. He didn’t know that he was going to do it. He was saying all kinds of things that were completely unrealistic in the middle of the revolution. He did not understand how the Americans were going to view him. If you were to say to him, “What do you think the Americans would do?” in the middle of the revolution, he would say, “Well, we are on the right path, and because of that, the Americans will support us.” Of course, his advisor would say, “that is not how politics work.” But that was not important for him. For him is was a conviction that “We are on the right path. I’m doing that thing, against all odds, and it is my historical responsibility to do it.” You saw the same thing among the Bolsheviks, whatever you think of them. It was completely unrealistic, but they succeeded. Or Fidel Castro. Most revolutions were carried into success by people who are not realistic, people who actually not only rejected the reality that they lived in, but also realism as we’re thinking about reality. They highlighted things like energy, vitality, basically conviction that one was on the right path, that one’s cause was just. That was the most important spiritual force behind any revolution that ever succeeded.

The other reason to actually get away from realism as a way of analyzing the situation is because of what we know about social science. I am a social scientist, so I know. I think I know what my colleagues do, and also what I do. What we do is that we try to analyze reality. We try to understand why the reality we have is what it is and not something else. That means you analyze reality and at the end, what we call understanding reality, is the way by which you figure out that the reality that we have right now is here because of structures that are necessary. It is here because of some necessity that my analysis has shown to be there, and because it comes out as the product of necessary forces, it has to be what it is. It can’t be something else. So sometimes even the social science analysis that is suspicious of reality, ends up by understanding things actually confirming this necessity. Revolutionaries don’t work that way. They tend to think of a way beyond reality, especially when the reality becomes so objectionable—as we see in Gaza today—so intolerable and to be the product of people who have the power to think that they are the ones who create the reality in the world that all of us have to live with.

So the no-state solution comes out of these clusters of factors. A way, out of necessity, to think beyond the limits of reality as we as we have it, with historical awareness of how things happened in the past, and awareness of how that reality was opposed by people from the law using various means. Violent as well as non violent. In order to move on the power of conviction that the cause was just, in spite of the fact that they were weak and much of the reality of the world conspired against them.

So I’ll stop here. Hopefully, if I missed anything, we’ll talk about it in the coming half an hour. I don’t know how much time we still have but in the remaining time.

Shuli: Thank you so much. That was really amazing. If you’re open to questions, I’ll facilitate the questions in the room. For people who are online, if you put questions in the Q&A section, I will be able to read your question to the room and to Mohammed. I’ll open it up if anyone wants to start the conversation, and then I’ll repeat what people say so you can hear Mohammed. I can also start.

I thought that was a really helpful outline of the situation and these prospects. When I when I’ve talked with other people about the idea of a no-state solution, the one of the things they say is that that’s unrealistic, but then, as you say, the other outcomes are intolerable. Because it also just involves so much death and destruction. Then you also talk about the actual social organization for Palestinians in diaspora—even under the apartheid regime—has this organic, horizontal, anarchistic way of living. I’m interested, because you’re also bringing in this sociological lens. The way that we talk about these things, versus the way that they’re actually lived, seems to miss some aspect of the that lived experience on the ground. So, just to open up a first question, what do you think the distinction is between the way that we talk about this issue over in the West—how it’s represented to us—versus the way that people on the ground are living it? I feel like even though we have sort of some kind of media representation—even made by the people who are there in Gaza—there’s something that isn’t being communicated over here and that we can’t see. So I wonder if you could speak a little bit about that distinction.

Mohammed Bamyeh: It’s a problem for global communication, ultimately. There’s a lot of things that we don’t know about Gaza right now. That’s intentionally so because of the killing of journalists. About 95 journalists or more at this point have been killed in Gaza, intentionally. They were clearly marked as journalists, and they were intentionally killed. So there was actually an effort to reduce the visibility of what is happening in Gaza and also reduce Gazan voices in our conversations. That did not prevent, of course, a solidarity movement from emerging anyway.

It is true that what we have here is the no-state kind of reality. This is a lot more present in Gaza right now, in the sense that all of the people are refugees (2.3 million people). They have to somehow rely on each other to survive more than ever before. That had already been the case before for this war, but even more so right now. So one thing that is really important is to try to convey those experiences to each other in a way that we can understand.

Now there is something global that is happening, not just about Gaza. In fact, the global protest movements everywhere, really, since 2011 did have anarchist features, like what you saw in Arab Spring. So that’s a global way of thinking about protest that is traveling around the world right now, especially among young people—who don’t pay as much attention to the regime media, but do collect information from all kinds of various sources. This is on account of connections to causes on the basis of more horizontal networks of transmitting information, that was the case before. The thing that keeps us going in the middle of these crises, is original thinking about solutions, as you see the human tragedy happening in front of you, that is produced by the powers that rule us. So what is happening in Gaza is possible because the American government is making it possible. The weapons are American weapons that are being used. The money is American money. The US is complicit in the genocide that is happening. So is Germany, by the way. So are other European countries. We must understand this complex complicity. Part of the solidarity comes out of the awareness that there is complicity, at least by governments, in the community crisis. Also, there’s the fact that governments that produce genocide—including the US government—are automatically illegitimate precisely because of the injustice that that they are doing.

Part of the trick is to really change the discourse. For example, in Europe, in the US, people talk about the right of Israel to exist. That’s taken for granted as a meaningful question but states don’t have a right to exist. They force themselves into existence and they exist because they have the capacity to force themselves into existence. That’s true of any state, ultimately. If we are talking about states having the right to exist, then the real question would be: does Palestine have right to exist? In fact, in that equation, Palestine is the one entity that could use a right to exist. The same thing about the right to self-defense that we see in the US and Europe as well, when Israel is attacked. Israel has a right to defend itself. Do the Palestinians have right to defend themselves? They are the ones who are under occupation. They are the ones who are a lot more vulnerable because of the occupation, than Israel. So part of what I think the communicative practice is—that we need to cultivate more of—is how to kind of create a new language out of the barrage of questions and dogmas that come our way to divert our attention from what we should be talking about. I don’t know if this is actually answered your question.

Shuli: Just as a quick follow up on this idea of the “right to exist”. It’s it’s very hard for people to think outside of the idea of national or ethnic determination, as the reason of existence for a state. So the two-state solution comes from this idea that everyone has their own state based on their own ethnicity, which is obviously not real. Do you think that there’s a possibility through discourse, of changing the idea, that gets so ingrained in our heads, that every people deserve a state?

Mohammed Bamyeh: I mean, in principle this is not wrong. We have to talk about the right to self-determination. Of course, the problem with the right to self-determination—as it was formulated—is that it is restricted to nations. So you have to be a nation in the Wilsonian version of it. You have define yourself as a nation, to get self-determination, but you can’t be anything else that is a not nation. So, we can expand the idea of the right to self-determination to various groups that do not regard themselves as nations, in terms of the state. If a two-state solution happens that would be preferable to the occupation. If you have a one-state solution where everyone is equal, that would be even more preferable to the two-state solution. If we have no-state solution then that’s preferable to the one-state solution, for all kinds of reasons I mentioned.

It’s not as though when we say no-state solution that it is the only solution that we can practically live with. Rather, we talk about order of preferences. Each solution along the way solves some problems but it may create others. It’s not an idea that is meant to be exclusive of other possibilities. Of course, a lot of people are committed to nationalism and nation states. You are not going to be able to impose a new state on them. The no-state concept of political life, does not get a life until it is presented at the table and becomes a part of the cluster of arguments that we talk about. So that’s idea: to expand the parameters of the thinkable, especially given that everything that we have to talk about until now hasn’t worked.

Audience Question: How would you describe the Palestinian Authority within the no-state solution? In particular, the current members of the Palestinian Authority came from the PLO who described the current work of liberation in state terms.

Mohammed Bamyeh: I think I heard most of that question: What do I think about the Palestinian Authority and its connection to the PLO? That’s what I heard.

Shuli: And how it fits into your analysis.

Mohammed Bamyeh: Well, the PLO is the combined cluster of the Palestinian National Resistance Movement altogether. All of it emerged from this goal, and it was not a state until, of course, the Palestinian Authority came in. The Palestinian Authority was meant as a transitional period, until you had final status negotiation that presumably would result in the Palestinian State. That never happened. What happened is that the Palestinian Authority essentially became reduced to a police force for the occupation. So the only thing that it does is simply make the occupation cheaper for Israel. Also it is not really a practical authority. The Israeli army can walk in, at any time, into the territory that is nominally under the control of the Palestinian Authority and arrest anybody it wants or simply shoot people. The Palestinian Authority, from an Israeli perspective, is regarded as something like a support mechanism for the occupation. It is not actually expected to develop into anything more than that. At best it will become something like Bantustan, in the South African Apartheid model. That is the most it can aspire to be.

Of course, what happened in the meantime is that the Palestinian Authority itself became essentially adjusted the role. It is not really doing anything more even though nominally, it is committed to the idea of Palestinian independence. It does not have the power to pursue that. It’s actually not doing anything other than perpetuating itself as an authority. It’s funding depends entirely on the outside world. It comes either out of donor countries—so it is dependent on the goodwill of those countries—or from taxes that are collected by Israel from residents of the West Bank. So the people who live under the Palestinian Authority, pay taxes to Israel, not the Palestinian Authority. Israel collects that money, and in theory, is supposed to send it back to the Palestinian Authority. That money gets withheld all the time (right now it is withheld) as a punishment for whenever the Palestinian Authority tries to do something for Palestine. For example by joining the genocide case against Israel in front of the International Court of Justice, or by asking for membership of Palestine in the UN—which just happened. Also the tax money was withheld from the Palestinian authority as a punishment for this. So it is not really an authority ultimately. Most Palestinians are now against it, and they want it to be dissolved. There is a demand right now for a new Palestinian election, where Palestinians do have, or should at least, have part of the right to self-determination: to determine who should be represented. So that’s where we are now.

Shuli: I’ll take one question from online. This says “Thank you for the talk. I was wondering about the connections and perhaps fruitful friction points between practices of Islamic life —worlds and practices of stateless, local organization and self-governance. How are these parts of your work connected, complementary, contradictory, etc.”

Mohammed Bamyeh: That’s a good question. It would take a long time to actually answer. I wrote a lot about Islam—not as a religion, but a social system over time. I was interested in finding out, why do we still have Muslims today? I am not a religious person, but I’m interested in religious people and why religions continue to exist and inspire people after the time/space of their creation, hopefully over centuries.

For me, the explanation was that religion survived to the extent that they provide people—not with doctrines, not with orthodoxies, but in everyday social life—with some kind of a pragmatic compass to everyday life. In a way, a religion becomes a way by which people talk to each other, across the class system and across the tribal divides, across linguistic divides. You have a way by which religions have started global systems, global citizenship across languages and ethnicity and so on, in a way that allows a global community to communicate across class interests. So the rich and the poor and the farmers and the etc, can actually talk in the name of the same religion, and express their interest in a religious language. That’s my approach to analyzing religions as kind of capable of surviving to the extent that they provide that practical, pragmatic concept and approach to everyday life. I’m less interested in religious authorities even though sometimes I do look at them, but I look at the ordinary pragmatics.

In terms of the area we’re talking about, the Middle East, we have a religious revival as of the late ’70s. That was relatively new and surprising because in the post colonial period most political systems and cultural life was dominated by a secular elite. Religion would seem to be on its way out as a historical force everywhere. So an upset—by the ’70s, you have religion coming back to life, not as a religion, but also as a political force. This was a new thing with the Iranian Revolution. Gradually many people who used to be secular leftists became Islamists. For example the founder of Islamic Jihad in Palestine was a secular pan-Arab nationalist with no connection to religion in the late ’70s. He saw the Iranian example, and said, “Well, this could work for us.” It is the same cause: sovereignty, independence, modernization, anti-colonialism, etc. We tried to do it through leftism. That took us only so far, but now the same cause, the exact same cause, can be carried through under the banner of religion.

What interests me is how these oppositional energies migrate from one ideology to the next. Of course Islamism is not eternal as a political force. In 2011, 2019 with the Arab uprising, there was actually very little religion in the revolutions themselves. Even though religious political parties benefited from the revolutions, they did not initiate them. They were thoroughly secular revolutions. By 2011 the oppositional forces also moved away from religion into something more like anarchism, unself-conscious anarchism. It continues to be somewhat there in an unorganized form. So for me, religion has a political force in particular as a guide to life in the world as part of a continuum of experiments and resistance that the little person does not control. It exists in the same mind like other ideologies. You can be, for example, a Muslim believer and an anarchist and also believe at the same time in the possibility of Enlightened Despotism. The mind of the ordinary person does not consist of one clear ideology. There’s a dialectic process that is going on and choices are made on the basis of experience as to which path you want to go down. That is how I understand religiosity, as part of a larger mix of strategies of resistance in the same mind, in the same society.

Audience Question: Do you think that the ways that Rojava has done its autonomous system could be a model for the no-state solution?

Mohammed Bamyeh: Rojava is an ongoing experiment. I think has to be looked at that way. So it is not really a finished system. It should also not be forgotten that it is one of the products of the Arab Spring from 2011. The same movements that we are talking about that produced all these revolutions across so many countries also produced Rojava. So it is really part of the larger picture of revolution. It just happened to work in Rojava, where actually people did take over power, for a while at least. I think a lot has been learned from it. I just met some academics who actually tried to build the full universities in Rojava that I just became aware of. All of them I knew, and they’re doing a lot of really interesting work. The thing about Rojava is that it also does not live in a vacuum. So around Rojava you have the Turkish army, you have Russians, you have the American forces, you have ISIS every now and then moved in, you have the Syrian army as well. So you have lots of forces in the area. I think it would work if it shows commitment to the principles out of which it was formed, which is inter-ethnic, not only Kurdish, not [only] Arab, but rather allows multiplicity of practices and types of conflict management within it. So it is there, and I think we can learn a lot from it. It is part of the larger cluster of experiments in self-rule that emerged in 2011, throughout the region. It is the one that we pay attention to, because it is the one that seemed to be more successful so far. But it is part of a larger movement across the whole region.

Audience Question: How do you see the future of nourishment, within anarchistic mutual support for life within community, while the colonial powers may ransack, poison and steal the land, given the continual killing of resources in this fundamental colonial practice. I’m thinking of the reality of land made not only unsustainable for life, but depleted entirely of nutrients for decades, particularly given the practice of foraging and self sustained practice within anarchists and survival communities. So the question’s about the land and the realities of that.

Mohammed Bamyeh: This is difficult language and a difficult issue to address. Gaza is an extreme case, in the sense that in the war, the entire agriculture of Gaza was destroyed, intentionally. Water purification systems were destroyed intentionally as well. Hospitals: all of them were attacked. All universities in Gaza were destroyed, level to the ground. There were 12 universities and all of them are gone. Two thirds of the schools are destroyed completely there. So the practice of war there is to actually make Gaza uninhabitable. This is a really clear goal of the war—to make sure that Gaza becomes uninhabitable, as a preclude to occupying it without its population. We never had a situation like that before, especially in full sight of the world, in real time. Now, when analogous processes happened historically they tended to make people cohere more together because they needed each other for survival. The extended family for example—which is there—became a lot more important than before.

Look at Libyan society under fascist Italian occupation. Remember, Italy was in Libya after 1911 and it became an Italian colony at a time when Italy became fascist, ruled by fascism. There was a resistance movement in Italy, in Libya against Italian fascism which resulted in huge massacres of the local population. About 1/3 of the population of Libya was killed during the fight against the Italian fascism. Concentration camps were built for the first time in Libya before they were built in Europe. Again, something I bet people don’t know. A huge amount of suffering resulted from that conflict against Italian fascism. One result of that war was the increasing of the power of tribalism in Libyan society. Why? Because the tribe—which was always there as an institution that you need in time of help, but not as an institution that is needed regularly—became a lot more important for people’s lives. So the tribe was actually a quasi-anarchist system. It did not call itself that, but it did not have prisons, did not have a police, it did not have executive council. It was simply a mutual help institution, that was available to help people who belonged to it, who didn’t necessarily know each other personally. They can travel across great distances and knock at someone’s door and they can help you. That in terms of culture, becomes a lot more important as an institution of a mutual help.

For a long time, I’ve been interested in these so-called traditional institutions, as part of the larger history of anarchism. We don’t really think of them that way—as part of the larger history of anarchism but they are in the sense that they are mutual help mechanisms that do not rely on police or force, that are voluntary in nature, that do not govern your everyday life, but they can provide help when help is needed in life. In times of conflicts like we have in Gaza and in other processes historically you find these traditions become stronger. Sometimes that results in society itself becoming more conservative. That’s part of the deal, really. That comes with it. So people adjust because they have to. In times of hardship they revive or give more credence to the institution that are familiar to them and already there. Sometimes as in the case of the Palestinians, over time they create new institutions like what you see in the eventual emergence of a revolutionary culture in the Palestinian refugee camps.

Audience Question: How do you see the transition from being a people without a state because of Zionist oppression, to a people without a state from a liberatory perspective?

Mohammed Bamyeh: I don’t know how that’s going to happen. I don’t have a framework for that, because I see these kinds of solutions, especially the ones that take an anarchist reason to be pragmatic projects. One knows more about the nature of this entity that we call a new state by doing it, one step at a time. One possible pathway is to actually pass through the state. So have a state that is committed to abolishing itself in favor of a more self-managed type of social structure. In order for that to happen you have to have, first of all, an awareness that this is what we want. People have to be actually convinced of it and that is really a part of the allure of anarchism, for me in particular. Persuasion is essential for the process. Anarchism, I think, is the only ideology that cannot be imposed on those who do not believe in it. That’s not true of others ideologies. It’s not true of Marxism, for example. You can impose it on people who don’t want it. It’s not true of fascism, which can be imposed on those who want like. It’s not true of liberalism either, which actually can be imposed on people who don’t want to be liberal. Anarchism is the only one where there is a self contradiction in the notion that you can force it on people who don’t want it.

For me, the appeal of the idea of the no-state solution comes simply from the fact that state-based solutions have been catastrophic. Very clearly so. Not just today, but over a long period of time. So there’s a reason to talk about the no-state solution, that comes out of empirically experienced reality. That reality is visible to millions of people, not just intellectuals, and has been visible to these millions of people for a long time already. It just requires the consciousness. It just requires the mental tools to imagine a structure that involves getting rid of the states as we know them. So when we talk about the reality of how to put something like this together we are talking essentially about communicative process, about persuasion, about planting the ideal on Earth. Once it is planted, hopefully, it becomes appealing on the basis of its superiority in comparison to what we have experienced, or what we know—which is horrible and genocidal and intolerable. That is where we are. How do we put it into practice? That depends on how many people are persuaded and how they want to put into practice. We can use existing institutions, if we want to, and if they’re capable of being used that way in order to push to a no-state solution.

Shuli: As an addendum to that: You talked about the precious memory of people having the experience of organizing themselves but then we also have this imbalance of force, of the police and the violence that they’re willing to use to impose their structures. I wonder how you think we deal with the confrontation of that force. Even if we had a mass of people. If they have overwhelming force, then how do we confront that?

Mohammed Bamyeh: By resisting it in any way, as Malcolm X says, by any means necessary. People have a right to resist occupation. They have a right to resist oppression, by any means necessary (although Malcolm X actually meant it rhetorically, I think). Also not entirely so, because the idea is that it is the people who live with oppression who have the right to decide the means of their resistance. Sometimes they use violence. Not necessarily because it’s practical, but because they want to show the energy of the struggle. They want to verify to themselves that they’re capable of doing something. They want to experience their agency. Not all acts of resistance are rational, in the sense that they are not intended to produce an exact result, or proven result. Sometimes you fight fully knowing that you’re going to fail. That is something you see in the first Palestinian Intifada, where you have young kids throwing a rock at a tank, knowing full well that the rock is not going to destroy the tank or end occupation. But by doing that you verify to yourself that you are still a capable human, that you have agency, that you are resisting and you’re showing that you are resisting.

When I when I think about resistance I don’t think necessarily about practical things. I don’t think about effectiveness necessarily. I have nothing against effectiveness or being effective. That’s not the point. Often it is the case that before we do anything that’s effective we have to verify to ourselves that we are capable agents to begin with and then do that by acting. Acting itself generates both. That is, it is possible to imagine a different world because I am acting at this point as a capable human. When you have more of those agents, you have a lot more successful movement. That is, for me at least, how resistance ought to be thought about: by any means necessary, but not necessarily in a way that is crazy, but in a way that is actually oriented to discovery of self-worth and of capacity in the world.

Shuli: That’s a beautiful way to wrap up the discussions. Thank you so much for sharing your analysis and ideas and taking the time to stream into our bookfair. Thank you. And if you want to, give Mohammed a round of applause.

Mohammed Bamyeh: I’ll be in touch, hopefully in the future.

Shuli: Yes, that would be wonderful. Thank you so much