This week, we’re sharing a recording of Andrew Zonneveld from the 2024 Another Carolina Anarchist Bookfair talking about his book All Will Be Equalized!: Georgia’s Freedom Seekers of the Swamps, Backwoods, and Sea Islands 1526-1890 alongside his friend Modibo Kadalie. To see a video with the slides from the presentation, check out our youtube page.

. … . ..

Transcription

Andrew Zonneveld: I’m going to give you a little disclaimer. I put the whole slideshow in one order last night, and then this morning, I got up and was like: “I don’t want to do it like that.” So I will be flipping around a lot back and forth, and I will try to leave a lot of time for us to talk. A quick check. Is there anybody in here who’s really keen on talking about the Okefenokee? Because I know that’s been an issue that people are interested in. I saw one hand go up. So there’s not maybe [a big interest]. We’ll talk a little bit about that issue and you’ll get a little bit of story. Are there any people here who are from Georgia or spending amount of time in Georgia? Sweet. Okay, great. So this is for you. I’m gonna toggle through my slideshow real quick and just talk a little bit about how this project got started. So don’t look, you’re not allowed to look. [laughs]

I was working on another book that’s very much based in coastal Georgia, and that manuscript is still forthcoming because I got distracted by this thing. And while I was doing the research down there in Liberty County, I came across this really cool archive online that a woman named Stacy Cole operates. It’s called “They Had Names”. Stacy Cole is a white woman who worked at the Midway Museum, and she realized that the museum’s archives didn’t record names of any enslaved people in Liberty County. She set about using ancestry.com and all kinds of different records that she could find to find the names of everybody who had been enslaved in Liberty County. Through finding those names, she found a lot of interesting documents that emerged at the tail end of the Civil War from something that was called the Southern Claims Commission. That was from when Sherman’s March to the Sea (we can talk about it more in-depth in a minute) arrived in coastal Georgia, there were many people and a lot of turmoil. A lot of people were taking a lot of stuff from a lot of other people. The idea was that some people who had been anti-Confederate might have had their stuff taken by the Union Army. And there was this opportunity with the Southern Claims Commission to say: “Hey, can you give me a little money for the horses you stole?” or whatever. It was intended for any white landowners who had been allegedly loyal to the Union. But a lot of Black people applied and did get paid, and a lot of Black people applied who didn’t get paid, it really depended on who the agent was you were talking to.

There was an elderly widow who had a little country store, and she was very poor. She had two adult sons who died by the time she was making her claim. But her documents really stood out to Stacy and to me and this is where I got the idea to write the book. I encountered this document where part of the Southern Claims Commission deal was that you had to find people who would bear witness for you and say that you had actually been in favor of the Union or been against the Confederacy or something like that, to get your compensation. And so this woman named Elizabeth Somersault was filing for this claim. What we learned about her was that around her little country store in Sunbury, Georgia (which was a ghost town even then, now it’s really a ghost town) all of her clientele, all of her neighbors, all of her close friends were people who were enslaved. Some [of those] people would buy stuff from her. In rice country, if you were a slave, you still could sell stuff at markets on Sundays and make a little money so they would buy meat and stuff from her.

Her store became this hub of anti-Confederate intelligence. She was passing news of the war to people who were enslaved on nearby plantations because they couldn’t talk about it. They couldn’t ask anybody about it. It was very, very dangerous for people to be heard talking about this. There were some testimonies given by some of her neighbors, including a man named Samuel Elliot, in which he says that “Elizabeth was all the time getting the news and telling us how the war was going on. And said the South would get enough of it pretty soon. She said she would not do anything for the rebel soldiers to save their lives. I never knew her to help them in any way. She said there was not one colored person in Liberty County who did not think well of her. She had two sons, John and James, who were strong for the Union. And there were very few Union men in Liberty County. I did not know any others myself. We were not allowed to talk much. They cut and slashed so much that I was afraid to talk and to ask anybody else. We used to go to her and to Ben for news when they were home.” What happened was that Elizabeth was telling everybody basically: “fuck the Confederacy” and stuff like that. And she was very loud about it. And her sons tell her: “Yo, they’re going to kill us. You need to calm down.” And she says that she kept on talking till her son, John told her: “He told me if I didn’t hush, I should be the death of him, for they would come after me, and he should have to fight for me. And that scared me, and I stopped.”

This paragraph that Mr. Elliot was recorded as telling the Southern Claims Commission really interested me: “She told me we would all be free soon, and she was glad, and she said so, for they (the enslavers) but all have to take the plow, as she had. She wanted to see them rich men all put to the plow and hoe, and then the country would be better off, then all would be equalized. And she said then that they could not ride the patrol anymore (the slave patrol, beating and harassing people and killing people and cutting up the colored people). That was her cry all the time from the commencement of the war till the close.” The Confederacy was conscripting every white man they could. Her son John went to Samuel, and as you can see here [on the slideshow], Samuel says: “He wanted me to take a hatchet and chop his fingers off, for he did not want to fight. I refused to do it. I didn’t have the heart to do it. Then he called Jacob Monroe (a slave) to do it, and he, too refused.” John and James, both her sons were eventually conscripted and then they immediately fled, and they hid in the swamps, people would sneak them food and stuff like that. So I became curious about how much of that was going on in Georgia. I also became curious about stories of interracial and multiracial anti-slavery activity in Georgia. It didn’t end up being the end point of the book, but I said, “I’ve got this at the tail end of the Civil War. How far back can I take this story? What can I fill it in between [with]?” It turns out, quite a lot.

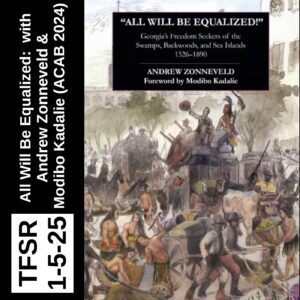

I wanted something from that period for the book cover, and I stumbled across this image here, which was a newspaper illustration depicting a rather chaotic, but in some ways jubilant and really energetic scene from Savannah, Georgia, at the time, where the Union was occupying Tybyee Island, which is right off of Savannah, for those who haven’t been [there]. It’s an interesting image, because there’s clearly a lot of diversity in the picture, both in terms of class and race. There are also people celebrating, some people who look scared, some people who look like “Hey, maybe something’s happening here.” I just thought this was great, and it’s wide, so you can wrap it around, you can do the front and back cover [of the book]. So I talked to some illustrator friends of mine about colorizing this. But then when I was talking to a dear friend of mine, Julia Simoniello, who lives in Staten Island, she and I hit on this idea of redoing the image, but including freedom-seekers from across Georgia’s history. So if you look at the cover image (it’s reproduced in black and white on the inside as well, and I try to post the full illustration online as much as I can so people can see this version) this is what Julia came up with. You can see a Seminole man raising a rifle on top of the cart. You can see the Timucua people, who we’re going to talk about in a second, down there towards the center of the image. You see some of the characters from the original design too. You can see some maroons hiding in the swamp at the bottom left corner there. All the characters that she put in here were derived from other illustrations from those various periods. Some of those illustrations you’ll see here.

So I’m going to go back about 400 years. There was this question of how far back can we trace multiracial or interracial anti-slavery solidarity in Georgia. It turns out you can trace it all the way back to the very first arrival of the very first known enslaved African people forced aboard ships and brought to North America. Does anybody know the year? No? I was hoping somebody would say 1619, and then I could correct them [laughs], but it was 1526. People who say 1619 are focusing on English colonies. But the first people who were enslaved and brought from Africa to the East Coast of North America were brought by the Spanish in 1526 to a small colony that we’ll talk about in a second. But I want to talk about what this part of the world was like right before that. In that moment where people arrived what kind of world were these slave people and also these colonizers arriving to? Coastal Georgia at that time was home to two distinct indigenous societies, the Guale and the Timucua, and they spoke two distinct languages. The Guale spoke a Muskogean dialect that we don’t have a lot of documentation for but it was some kind of Muskogean dialect. For the Timucua language, we actually have a Spanish translation dictionary for it, although that language has not been spoken in many hundreds of years but there is some documentation. That language was distinct because it was more similar to the language of the Warao in South America than it was to anybody who was in North America. The Timucua were in the South Georgia and North Florida area.

So it’s important to also think of the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico as a conduit, not a barrier to intercommunal, intercultural trade, and so forth. Keeping in line with Modibo’s analysis of similar histories, I leaned on his work, “Intimate Direct Democracy” for some of my analysis and you really can see that this was a society that were networks of eco-communities, both along rivers and intercostal waterways. They were economies of immediate use, equal distribution, and ecological symbiosis. So these were not people who were growing things to build a huge surplus to use to control people or sell at markets and enrich themselves, or something like that. It was very much immediate use. There was trade, but trade had a different role than maybe we’re used to thinking of. The most obvious example of this is that in both of these societies communal food stores were open to all. There was a French explorer who remarked that anybody could just come into these food stores, take whatever they needed, and leave and there seemed to never be any conflict about it. And he said something to the effect of: “If only we could get Christians to act this way.” I got a kick out of that [laughs].

As Modibo has observed earlier, these were also an intimate direct democracy. You could really describe these communities as direct democracies, where decisions are not made by commanding individuals or elites. This is where there’s really some conflict historiographically that Modibo mentioned earlier. There are a lot of books that are a little bit old, and some scholars who are a little bit old are going to tell you that this or that society has these rigid stratifications of this, that, and the other. And the more you dig into primary sources…there’s a big asterisk on that because primary sources are also all colonial, those surviving primary sources. So you have to read those really critically and you have to be able to understand when the person who’s writing that original primary source document is projecting European ways of thinking onto the Americas or onto the Western Hemisphere. And also, very importantly, these communities were very gender diverse. This is something that every colonialist who visited the area prior to the establishment of any colonies remarked about. There were different levels of pearl-clutching with this situation. But these were very gender-diverse communities. There were at least three recognized genders, probably four, and two-spirit people had very distinctive and important roles in their communities, which also was debated by colonialists at the time and historians today. We make an argument about it and I think we’re on the right track.

So here are some images that some colonialists drew. This was by a French guy named Lemoine. I think this was by a Dutch guy, not sure. But here is a great [picture], this is people taking food to food stores. Generally, there was a lot of foraging and growing happening on islands and then they would harvest and move the food to the food stores on the mainland. If you look at the front left, this is a procession of people moving food. They did a lot of stuff just by foot. But these two folks in the front left, are two-spirit individuals. And the way archaeologists know that is from the way their hair is worn in there and the type of dress that they’re shown as wearing. These are intended to be a documentation of two-spirit individuals. What happens when these Spanish people traffic enslaved African individuals into coastal Georgia, which, by the way, the exact site is not known, but this initial colonial attempt happened somewhere around Sapelo Sound. So if you’ve been in that part of the world, in the Sapelo Island, or Harris Neck, or anything like that, a very significant moment in world history went down there.

The colony that the Spanish tried to establish there, failed entirely. It just pretty much collapsed, because they didn’t know how to deal with living in the low country. They dug their latrines too deep and poisoned themselves. Everybody started to get really sick. The African people saw an opportunity for liberty, for self-emancipation, and they took it. Interestingly enough, and no other book [mentions that]. This is where I’m gonna brag a little bit. If you read a book about Guale, they’ll tell you there was an attack by the Guale at this time. If you read a book about the history of slavery, they’ll tell you that there was an uprising of enslaved peoples at this time. But these things happened at the exact same time so I think that’s significant [that] it coincided. This African rebellion in coastal Georgia, the first African rebellion on the Eastern part of North America, and possibly North America in general, happened right there in Sapelo Sound and was distinguished by a militant solidarity from Indigenous peoples.

The Spanish who lived fled back to Hispaniola. The Africans who were there, they had to stay, because they had no way of getting back across the water. And so where did they go? Well, the pretty obvious answer is they went to one of these ferries. You can see the map. I don’t know how good you can see it, but you can see the little dots. The dots that are around San Miguel de Guadaldape, they’re all Guale communities. If you look to the South of the Timucua area, it’s also worth noting that everywhere where you have a city in coastal Georgia or North Florida, these were all sites where Indigenous people had cities. for example Seloy, that’s where St Augustine is now. Tacatucuru is Cumberland Island. So if you’ve been to Cumberland Island you might have seen some references to that in the museum that they have there. This totally embarrassing attempt at initial colonial thrust into North America failed for the Spanish, but they’re a very tenacious bunch and they keep coming back. The Guale, by the way, are ancestors of the Yamasee. So if I don’t get a chance to mention that earlier, I’ll mention that later.

Then you have the Spanish mission system come up. I’m just going to briefly go through this, but this was a really cool map I found that’s also reproduced in the book. Very hard to see, probably for you in terms of reading. But I was pleased that in the book if you put your face real close, you can read it pretty nicely. All of these things here [on the map] are Spanish missions or indigenous towns, and there’s a lot of them. The missions were also in the town. So a mission had its own name, the town had a different name. The mission system was basically an attempt to use religious conversion to undermine indigenous economic and political life. It was super insidious. I go into it in the book a little bit. It’s an interesting subject. If you haven’t read about the Spanish missions (they extended from Florida through coastal Georgia into the Carolinas) it’s super worth reading about. We get into it in the book and if you look at the footnotes, there’s more books that you can get into if you’re interested in that kind of stuff.

Guale revolt: so there was a series of indigenous revolts that happened. And these things are so important because these are revolts that are happening specifically because these Indigenous people are concerned about being enslaved. And why are they concerned about being enslaved? Because they’ve been living with 100 people who had been enslaved by the Spanish, and they had their children and grandchildren, stuff like that. This has certainly, by this point, entered into the popular discourse of “you can’t trust those Europeans.” So there was a lot of conflict among Indigenous people about how to engage with the Europeans, who were assholes, but also had a lot of cool stuff that people wanted. The trade was very exploitative. One day in 1595 a Guale man named Juan Mio is pissed about the specific grievance that he had and he just can’t take it anymore. He comes into a mission that’s on St Catherine’s Island, which has a whole long, interesting history. He arrives at St Catherine’s Island, walks into the mission, kills a Franciscan friar, and makes a speech. I have a little quote from the speech. It’s a much longer speech than this. It was recorded by the Spanish. I mean, who knows what liberties they took, but it’s interesting shit that he says here: “All they do is reprimand us, treat us in an injurious manner, oppress us, preach to us and call us bad Christians. They deprive us of every vestige of happiness that our ancestors obtained for us in exchange for which they hold out the hope of the joys of Heaven. In this deceitful manner, they subject us, holding us down to their wills. What have we to hope for, except to become slaves? If we kill them all now, we will throw off this intolerable yoke without delay.” And they went to work and the Spanish ran for their lives, they fled the area for about six years, and then they came back, and they were like: “We promise we’ll be really good this time.”

They kind of ease their way back, very sneaky bunch. Don’t have a picture for this one. Timucua revolt happened 60 years later. This was really like a general strike that followed the forced relocation and ethnic cleansing of all the Timucua communities surrounding and inside the Okefenokee Swamp. This revolt failed because the Timucua needed some assistance from the Apalachee, which was not forthcoming because there was some bad blood there, I go into it in the book. English colonialism comes around. I apologize for not giving a content warning here because this is a disturbing image. When English colonialism went down, slavery, the Atlantic slave system, came full force into the Eastern coast of North America. The most significant event where that’s concerned for the region we’re talking about is the establishment of Charleston. From there on, you have this power struggle between the English and the Spanish over control of this part of North America. Amid that power struggle the English were trafficking millions and millions of people, 12 million in total. A lot of those people were trafficked to Brazil.

Rice was the cash crop of the region. They were targeting specifically people who knew how to grow rice and they were appropriating this African science and technology forcibly in the Carolinas and then eventually in Georgia. This is a famous image many of you have probably seen depicting rice production in the colonial South, or this might actually be closer to the pre-Civil War period. There’s a problem for the English, which is that the Spanish hate them and don’t want them on the continent. A lot of people who are being enslaved in the Carolina colony are finding this out and are very astutely making use of this competition and they’re fleeing south to Florida. There’s a big difference between Spanish colonialism and English colonialism in this region. The Spanish were not creating agricultural colonies. They were there to exploit relationships with Indigenous people and do some kind of extraction and just hold down this kind of strategically valuable part of the world that was important for them in getting their treasure fleets back to Europe. The English wanted Indigenous people to die, they wanted to take their land and to use enslaved labor to cultivate cash crops so that they could sell it on a market. But because enslaved people knew about the conflict with the Spanish they would flee, often south across the Spanish lines.

There weren’t enough Spanish people there to police this [territory] at all and so they didn’t really try. And eventually formerly enslaved, self-emancipated. people establish Fort Mose, which Modibo writes eloquently about in the second half of this book. If you haven’t read the book, Fort Mose is considered the first legally recognized free African community in North America. There’s a museum on the site, just outside of St Augustine, that you can visit today. I really recommend that you do because that museum, as people can attest, is the product of local activism there and it’s a significant place. So some asshole named Oglethorpe approaches the [English] crown with an idea. He’s like: “I got these guys, some trustees and some rich people like me, we think we should have another colony. And we think the way to solve this problem of marronage, people escaping slavery, is simply to create a new colony between the two and in that colony, we’ll have no slavery.” This misled people into thinking that Oglethorpe was anti-oppressive. He’s not. The reason why he’s saying “there will be no slavery in this colony called Georgia” is because he wants to create a whites-only buffer zone, where people would be on the lookout for anybody who was Black escaping slavery and heading South. Also, they could establish some military outposts like Fort Frederica on St Simon’s Island, from where they could launch attacks against the Spanish, which they did. They eventually destroy the first Fort Mose and they rebuild it. That’s the whole other story, which is in this book, and you should buy it.

So what were they going to do? These landowners don’t want to work. So where are they going to get their coerced, cheap, or free labor? Well, just so happens in Great Britain, there’s this thing going on called “the enclosure of the commons” and there are a lot of landless working people who have no land to work on and are very poor and are coming to London and having not a great time, getting to debt, getting thrown in prison. And Oglethorpe is like: “Ship them over here.” So they ship over a bunch of what they call “indentured servants,” but they were going to be agricultural workers [in the colony], and it’s a bad scene. About a quarter of them died in the first year after founding Savannah, and then a lot of others escaped into the same swamps and backwoods that enslaved people from the Carolinas were escaping into. In the book, there are a lot of people escaping into swamps and backwoods. That’s pretty much the theme of the book. A lot of people go into the swamps and backwoods, and what they do when they’re in there is interesting stuff. So that plan doesn’t work out. People who’ve been granted land in Georgia protest, and they’re like: “We want to be rich, like those planters in South Carolina.” Eventually, their protests were successful and by 1750 slavery was allowed in Georgia. That initial period is called by historians the “Georgia Experiment” and it was the only one of the original 13 colonies that was founded initially with a prohibition on slavery. Like I said, it didn’t last long, but it’s an important period to consider. There’s an illustration of Savannah while it was being constructed, which was being sent to the trustees in Britain.

So what are people doing when they’re escaping into the swamps and backwoods of Georgia? As the Georgia colony and slavery expand, African runaways, self-exiled crackers…that was a name that white people who ran away from colonial society came to be called – crackers. They were really considered an undesirable cast of white people and were hated very staunchly by the land-owning class and various rulers and surviving communities of Muskogean-speaking peoples. They all encountered each other in Georgia’s swamps and backwoods and there were plenty of venues in this period for the expression of interracial solidarity, including, of course, illegal activities. So they would often get together and raid plantations, raid trade routes, or engage in piracy on the high seas. This is coinciding with that Golden Age of Piracy, you know, Pirates of the Caribbean, all that kind of stuff. This is that period, and it’s really interesting. Pirate ships are really fascinating. If you haven’t had a chance to read Marcus Rediker’s book called “Villains of All Nations”, and you’re interested in pirates, you have to read that book. It’s really freaking cool. A lot of freedom-seeking people went on to become pirates. And the term “a short life, but a merry one” is an apt description. It was a very dangerous work, but it was people who didn’t have a lot of options, who were just trying to live free for as long as they could.

Jail is another venue where interracial solidarity takes place. In Savannah jail, they couldn’t segregate their population for some reason, didn’t have the ability. So people would break out of jail together and stuff like that. In the woods, an important takeaway is freedom-seekers formed multi-racial communities of resistance, in which everyone participated in decision-making and leaders, where they existed, generally held no coercive authority. What we learned from Modibo’s book about the Meco system in Muskogean societies, there are really interesting parallels in Seminole communities and also on pirate ships. Authority and anti-authority worked the same way. I don’t want to take up too much time, so I’m gonna move along. Here are some maroons in the swamp. Here are some crackers in the woods. Here are some pirates doing their directly democratic Pirate Council. Literally, the name of this illustration was “The Pirate Council”, that was cool.

Things I’m skipping over, 1776 – a lot of stuff happens [that year]. Most importantly, the Black loyalists. These are people who sought freedom behind British lines and were relocated to Nova Scotia. Very, very important. The same exact damn thing happens in 1812 except it’s even more people, and a lot of them leave from Cumberland Island on the Georgia coast. We talk about that in the book. Seminole War…so after the US became a thing, Andrew Jackson wanted Florida, basically, and they’re having this problem still with Seminoles. By the way, the word “Seminole”…are people generally familiar with the word “maroon”? We know that “Seminole” comes from the exact same root. “Maroon” comes from “cimarrón”, which was a kind of Spanish appropriation of a Taino word. There are arguments over the definition, but one of the definitions I like is that it means “flight of an arrow”, and that’s a very common expression that is used to refer to people who are fleeing for freedom. If you look at “cimarrón” – “Seminole,” it’s basically the same slur that they’re using to refer to freedom-seeking people. The term “Seminole” was used by the Spanish in Florida at this time to refer to these groups of people. Who were Black, Indigenous, and there were some white people there. It was kind of a catch-all term, and the US even recognized this. Andrew Jackson, when he does his campaign of attacking these various maroon and Seminole communities in North Florida, explicitly says to attack anyone, regardless of color. It’s very interesting. There’s a great story I really like in the book about some Scottish pirates named Alexander Arbuthnot and Robert Ambrister, and some terrible shit happens to them. I could go all day on this particular battle of Old Suwannee Town. One of the communities that we’re talking about is technically outside of Georgia but it was known as Old Suwannee Town. It’s right there on the map. They fought Andrew Jackson and suffered losses but fled into the Okefenokee Swamp where they lived on Floyd’s Island. I met somebody earlier today who had just camped at Floyd’s Island. If you go to Okefenokee and you camp at Floyd’s Island, you should know that’s kind of hallowed ground. A tremendous history of resistance took place there. (It’s a nice painting. I think it’s actually painted by a marine or something, but it’s the Seminole War. For a while, I didn’t like the fact that there was a flamingo, because there are no flamingos in North Florida. Now there are flamingos in North Florida thanks to climate change.)

I’m going to skip Jackson. Jacksonian Democracy was an attempt to offer the vote to poor white people as an attempt to reel them into US statecraft, which we go into in depth in the book as well. And I’d already talked about the Civil War. I would get one more quote from this guy, Jesse Wade, from the Civil War, because he understood class. He was a self-identified cracker and he was referred to as a cracker by the newspaper journalist who wrote this. He was talking about the Civil War in class terms. He said (I’m gonna have to do an accent here, and I’m gonna try to get my Georgia out. Bear with me): “The rebel army treated us heaps worse than Sherman did. I’m a refugee, left everything care of my wife. I had four bales of cotton, and the reds burnt the last bale. I had hogs and a mule and a horse, and they took all. They didn’t leave my wife near a bed quilt. When they took what they wanted, they put her out of the house and set fire to it.” And then he says something interesting, “Mary, one of my boys fit again’ the Union. They was conscripted with me. And one night we went out on guard together, and we did, and we just put out for the Yankees. Sherman was up here to Kennesaw Mountain then, and I left. I did the joining. All the men that had a little property was for the war, but poor people was against.” I like that from Jesse.

There’s a lot of stuff I didn’t get to talk about here, so I wanted to leave some time. I don’t hope we have time for any kind of conversation or something like that, but please feel free to add stuff.

Modibo Kadalie: This is a concrete example, several examples, of how racial solidarity existed as the people resisted America invading them. America never was democratic. I mean, that’s just bullshit. These people were democratic. America coopted everything they had, took everything they had, and then perpetrated themselves and protected themselves throughout the world of the democratic society. So what we try to do is bring a new perspective to this. Most of the stuff that’s taught in school now is from the perspective of the American nation-state as a civilizer of the world. And they are really retrograde. They [the American nation-state] really are bringing barbarity and killing and stuff throughout the world. And what Andrew has done, which I appreciate, is he’s taking examples and shows. At the very beginning, they weren’t doing it. Then the people were solid. There was no Jim Crow. I mean, a cracker in the woods – he was running too. People are writing from the perspective of Jim Crow now and they interpret this stuff as if there was Jim Crow.

Andrew Zonneveld: We talked about this before, Modibo, you correct me if I’m wrong. What you’ve often said is people project Jim Crow further into the past than the actual Jim Crow period. Oftentimes, when we look at history, we assume that if we look back in history we’re going to see worse and worse racism, and we’re going to see another version of Jim Crow further back in history. But in this time, when ideas of what we understand as race now are not really solidified, in this earlier period, you find a lot more solidarity than you might expect. Is that what you’re saying? Yeah. And on Jim Crow. The actual Jim Crow period – in the book we make a case that this was, in my opinion, one of the most successful propaganda campaigns ever perpetrated on Earth. It’s really horrific. Because the question comes up, if there’s all this [inter-racial] solidarity [before], what happened? And the answer is: the Jim Crow period. That’s something that we that we go into in the book quite in depth.

Modibo Kadalie: Okay, we’re open to the discussion. Are there any questions or comments that people would like to raise, raise your hand. Could you talk a little louder?

Audience 1: I’m curious how later, during the period of emancipation and then reconstruction, broadly speaking, what was the status of these autonomous communities that existed prior, and did these communities absorb newly-freed, formerly enslaved people?

Andrew Zonneveld: That’s a really good question. I have to pause that because we’re constrained by time. And maybe next time I do the presentation, I’ll reorganize a little bit so we can do more reconstruction stuff. But Modibo, do you want to speak to that?

Modibo Kadalie: These communities still exist. I grew up in Crossroads, Georgia during the segregation period. The community down the road was called Briar Bay, and it was all-black. And it was a remarkable amount of self-organization and democracy, the churches, the Baptist church. You know, I’m an atheist now but I grew up in a Baptist church, and the Baptist church was organized democratically. Everybody voted on the preacher. When the preacher got too outrageous they threw him out. I was talking to Andrew today about how Gabe Wright, who was a personal hero of mine in my community. I remember the day when he threw Rev. Moore off the porch. You know, Rev. Moore was talking about, “I’m ordained by God.” And Gabe Wright said: “No, this congregation called you, and now we’re voting again, and we voting you out.” Even the PTA was democratic, but as time went on, they were eroded. I call it a state creep. It was eroded. And even under your feet, you see it disappearing and reemerging in some other place. But you see it disappearing.

Andrew Zonneveld: So just to add on to that, right at the end of the Civil War in the early Reconstruction period, you might be familiar with everything that was going on on the Georgia coast and the Sea Islands, concerning Sherman’s Field Order 15, which we didn’t get a chance to go into here. But essentially, Field Order 15 provided that 30 miles from the coast was going to be a reservation in which former plantation lands were divided among formerly enslaved people. Formerly enslaved people were already dividing those lands among themselves with this kind of revolutionary moment that was happening at the end of the Civil War. It’s a very important distinction to make, and they were forming communities that still exist now. Briar Bay is one of those. The great example of Briar Bay, which you talk about all the time, is that there was a rice plantation there that was owned by a white family called the Lacans, and if you go to Briar Bay today, you will see mailboxes Black families up and down the road, let’s say Lacans from the mailboxes, they’re still living on land that they won through struggle at the end of the Civil War. That’s something that we go into in the book, and that specific example is the subject of a forthcoming work that we’re putting together.

Audience 2: In your books, have you talked about or have you found sources on the nitty-gritty, on how early maroon communities lived? How they got their food, what kind of shelters they lived in, how they stayed concealed, and how they resisted?

Andrew Zonneveld: So for folks outside, the question was, what kind of historical information do we have about the day-to-day lives of maroon communities and Seminole communities? And the answer is that it depends on where you’re looking and which communities you’re looking at. These were people who had to constantly change the way that they were living because they were living on the run, and so they were establishing themselves wherever they could. But oftentimes things had changed. What you can see and what’s documented is always documented by people who hated them and were chasing them. So it’s sometimes hard to tell, but what you can see is a surprising amount of holdover from the earlier Guale and Timucua period. And if you talk to people who self-identify as Yamasee in Georgia today, there’s not many, but they’re there, you’ll hear some oral history of how we harvest shellfish and stuff like that. And it’s also, in the end, part of the Gullah Geechee tradition as well, slightly removed, but it’s still there. So the answer is yes, but it’s not uniform and it changes over time. For some periods you have more information, for some areas you have more information. With time and geographical location I think there’s a lot of variation.

Modibo Kadalie: And I just want to implore you all to be more sensitive to what you see and be more communicative to what you see. Because sometimes the stuff is so hidden and we are so indoctrinated, we can’t see it, we don’t understand it. And that’s what we’re trying to do. We’re trying to get people to be sensitive to this kind of thing because it’s right in. It’s right in. It’s not like some remote way past, it’s right here at our feet even. When there’s a crisis, say there’s an ecological crisis. If you have ever been in a flood, or been in a place where there’s a fire, something like that. People come together. You know, it’s almost like a reflex. They come together and they serve one another, even the assholes they carry water too. [laughs] That’s just the way the human beings respond. And they’ve been responding. That’s why we’re here. We’ve come a long way over the 20,000 years that human beings live in groups that can be documented. Over 20,000 years, or 200,000 years as a species. But I mean, we’re here, and we inhabit most of the inhabitable places of the world. We had to be working together, otherwise, you would be extinct. We would be some minor species or something. We’re all over here, and we’re beautiful too.

Andrew Zonneveld: Okay, the meeting should adjourn. If you want to pick up any books, we’ll just be right over here to our left. Each of those books are different prices. My book is 25 [dollars], you know, over the years, the price went up. We had a big crisis in printing. So now 25 bucks per book. But there are other books that are also more affordable. Thank you very much.