This week we spoke with Moira Meltzer-Cohen, an anarchist and lawyer with the National Lawyers Guild who practices mostly in New York City. For the hour, Mo talks about knowing ones rights and risks during interactions with law enforcement in the US during Trump 2.0, why even scofflaws should know some basic Bill of Rights trivia, info on warrants and house visits, airports and borders, and the importance of face-to-face practice with local lawyers who know the legal precedents on the ground in your jurisdiction.

Links

- NLG Anti-Repression Hotline: 212.679.2811

- NLG website: https://www.nlg.org/

- CUNY CLEAR website: https://www.cunyclear.org/

- instagram: https://www.instagram.com/cuny_clear/

- LLWD episode with Mo on Federal Grand Juries

- Our past episodes on Grand Juries and Grand Jury Resistance

- Magic Words flyer to stick on the back of your door in case of police visits: https://thefinalstrawradio.noblogs.org/files/2025/05/Magic-Spell_2025.pdf

Announcements

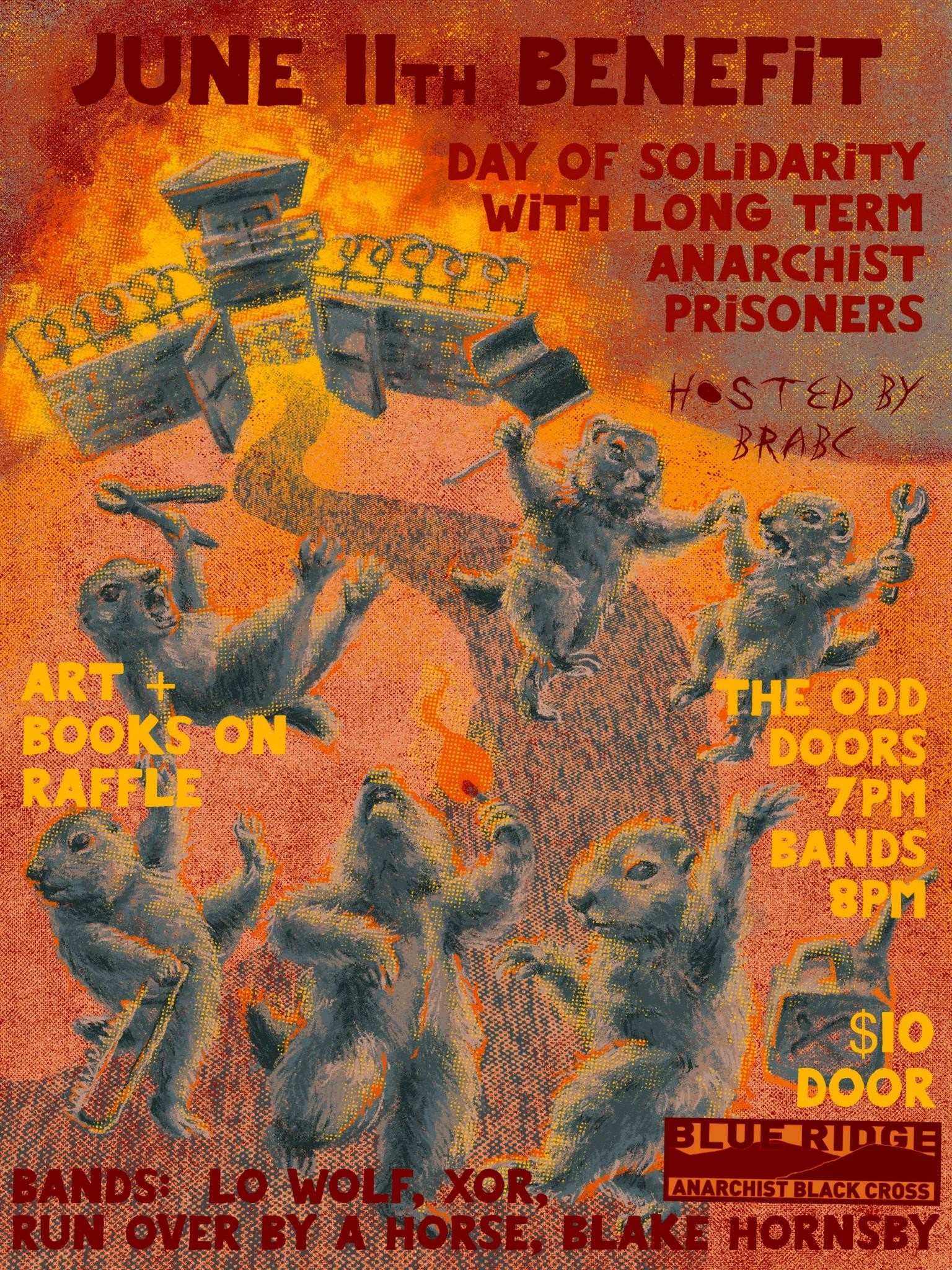

June 11th, 2025

Asheville

We’re a week and a half out from the annual June 11th Day of Solidarity with Long Term Anarchist Prisoners. If you’re in the Asheville area, Wednesday, June 11, 2025 at The Odd (1045 Haywood Rd near Firestorm in West AVL) . $10 door, opens at 7pm, music at 8pm

We’re a week and a half out from the annual June 11th Day of Solidarity with Long Term Anarchist Prisoners. If you’re in the Asheville area, Wednesday, June 11, 2025 at The Odd (1045 Haywood Rd near Firestorm in West AVL) . $10 door, opens at 7pm, music at 8pm

Featuring XOR, Lo Wolf, Run Over By A Horse and Blake Hornsby with lots of free lit and prizes available including books, stickers, clothing, jewelry and more.

- More info on the mastodon post: https://kolektiva.social/@BlueRidgeABC/114589079620149305

- Also coming soon at the BRABC website: https://brabc.noblogs.org/june-11th-2025/

Elsewhere

If you’re elsewhere, you can check out announced local events in your area by checking out the social media accounts for June11.Noblogs.Org, particularly their mastodon account on @june11@kolektiva.social

Fire Ant Movement call to action

Finally, the Fire Ant Movement released the following statement concerning June 11, 2025:

“Fire ant movement defense, an organization that works to gather mass opposition to the political prosecutions of the stop cop city movement in atlanta, is calling for a “movement defense day of action” on June 11 to support stop cop city defendants and long term anarchist political prisoners. Their statement reads: This year, June 11th arrives amid growing repression: Pro-palestine protesters are facing indefinite detention in ice facilities, and in Georgia, the state continues its aggressive persecution of the stop cop city movement, with 61 activists currently facing RICO charges.

In response, we call for a united front, to link the defense of the stop cop city struggle with the june 11th tradition of solidarity with long-term anarchist political prisoners.We invite people to learn about Marius Mason and other long-term anarchist prisoners, host public events, drop banners, throw fundraisers, and take action to defend our movements for total liberation.”Fire ant movement defense says that this will be the first of many movement defense days of action, drawing connections and lines of solidarity between movements fighting for liberation. You can find more information at fireantmovement.org and follow them on instagram, twitter or bluesky.”

They also wanted to point people to learn more at supportmariusmason.org and weelauneethefree.org

. … . ..

Featured Track:

- Know Your Rights by The Clash from Combat Rock

Transcription

TFSR: Would you please introduce yourself for the audience with any name, pronouns or any sort of affiliations you want to share?

Mo: My name is Maura Meltzer-Cohen, everybody calls me Mo. I prefer no pronouns, gender neutral pronouns. I am an educator, abolitionist and attorney. I spend a lot of time teaching people in liberation movements how to deal with the law, I spend a lot of time teaching lawyers about how to effectively represent people in liberation movements, and I am a member of the National Lawyers Guild.

TFSR: Thank you so much for taking the time to have this chat. I really appreciate it.

Mo: It’s my pleasure. I think these Know Your Rights conversations are so important. Maybe we should say, Know Your Risks conversations. I think they’re so, so important because a lot of times people get frozen up when we start talking about law. It can be really alienating, and not having the information is really dangerous. I also think hearing someone talk about the law can be really frightening, especially if we’re talking about State repression. I’m not here to frighten you or your listeners. I really want to empower your listeners to feel confident about what your rights are, to give a lot of reassurance about what your rights are, while also being really honest about what the limitations of the law are. The State has a ton of power, but so do individual humans, particularly people who are being charged with criminal offenses, right? We do actually have a lot of rights and a lot of protections. So I am going to say a lot of stuff that’s going to sound pretty scary, but I don’t want anyone to walk away from this program feeling frightened. I really want people to walk away from this program feeling courageous.

TFSR: Yeah or at least better informed and able to make more conscious decisions in terms of like understanding some of the processes that they’re that are being forced on them. Right, right?

Mo: Exactly. If anyone has decisions to make about how or whether to engage in ways that are likely to bring them into contact with the State, I at least want people to be able to walk into making those decisions with their eyes open.

TFSR: If there’s one simple takeaway, if someone has to turn off this podcast now, what do you want them to take away, in terms of Know Your Risks/Know Your Rights with law enforcement in the US?

Mo: The absolute most important thing that everyone needs to know (I actually have it written on the back of my business card) is that you have a right not to speak to police or answer their questions, and you have a right to an attorney. I’m going to say this so many times probably, but you should feel extremely comfortable exercising your right not to speak to cops and to have counsel. The way that you can do that is by saying, “I’m going to remain silent, and I want to speak to a lawyer.” I really want people to understand that asserting those rights, asserting all of your rights, is not evidence that you have anything to hide. It is the safest thing to do for yourself and your community. Just to unpack that a little bit, there is never a compelling reason to speak to police before speaking to a lawyer. So if cops or federal agents stop you or come to your door or call you on the phone, all you need to say is, “I’m represented by counsel. I need you to leave your name and number and a lawyer will call you.”

I guess the last little piece of information that I want to get out for anyone who has to tune out right away is the National Lawyers Guild, Federal Repression Defense Hotline is live at 212-679-2811. If you are contacted by federal law enforcement or given a subpoena to a federal grand jury, you can call us at 212-679-2811, to have a privileged conversation about your rights, risks and responsibilities. We can work to put you in touch with appropriate legal resources in your area. I’ll give TFSR a document to upload so that people can access it, print it out and tape it to the back of their door. It’ll remind them what to say if they have such an encounter with law enforcement.

TFSR: Cool. Thank you so much. It’s really helpful, having those sort of takeaways and having those sort of numbers and statements, like repetitious terms, magic phrases as they sometimes call them. “I have the right to remain silent” and “I want to speak to an attorney,” or I’m represented by counsel”, I think those things are really helpful ways for people to be more empowered when they’re having those interactions. The past few months have seen federal law enforcement, Department of Justice and the executive branch claim a lot of privileges and rights to detain, deny due process and deport people to third party countries in some cases. Does the law protect people from these sorts of situations? Have the laws changed just because there’s a new hairdo in office?

Mo: People ask me a lot, “Well, what does the law say about this? What does the law say about that? Is this illegal?” The sort of flippant answer that I always give is that the answer to any legal question is: nobody knows. The reason is that the law isn’t a static thing. It’s always a set of arguments, right? There’s a really big difference between what the law says, how the law is enforced by police and how the law is interpreted by a judge in a courtroom. Now, this administration is making a lot of policy changes. It’s making a lot of announcements about the law. It’s making a lot of claims about the law. There are all these executive orders, and they’re really frightening. I’m really not trying to be dismissive about this, but a lot of them (all of them, I think) are being subject to judicial challenges. People are suing in the courts and it’s kind of heartening that the courts (including at least seven of the nine unelected God/Kings at the Supreme Court) are standing up to these executive orders and saying, “actually, this is not permissible.” So as we’re seeing the attorneys and the impact litigators bring these challenges, the courts are saying, “No, actually, you can’t just change the constitution by fiat in this way.” It’s really important not to panic too hard and to understand it has always been the case that there are differences between policy, practice, the law as it is written and the law as it is interpreted. These things are always in tension with each other.

Another thing that people ask me all the time is, “well, when can the cops kick in my door?” The answer is, and has always been: whenever they want to. Whether or not it’s lawful for them to kick in your door or to have kicked in your door is something that I can’t tell you ahead of time. It’s something that a judge is going to decide down the road. I was talking to a mutual friend of ours actually, about how it’s really weird as an anarchist to watch the government dispense with the rule of law, but that doesn’t make the government anarchists. What they’re doing is they’re dispensing with, or they’re trying to dispense with the laws that act as a constraint on State power. Again, their efforts to do that- I’m not going to say they have no impact. They clearly do, but I don’t know that they have a permanent impact. That impact is certainly not evenly distributed. What we’re seeing is an escalation, but really just an ongoing continuation of what we have always seen, which is the Constitution has never actually constrained the behavior of law enforcement in real time. We continue to have constitutional rights. It remains important to be confident in your rights, to know what they are, to know how and why to invoke them, and also to understand what invoking your rights will and will not do right? So I certainly don’t want to be dismissive about people’s concerns, but what we’re seeing may be a change in policing, an escalation in policing, obviously a redistribution of even more resources toward policing. That does not mean that the law has changed. It does not mean that your rights have changed, and it doesn’t mean that the way that I would recommend people interact with law enforcement has changed. This is probably a good time to say that nothing I say during this program can be taken as legal advice. I am going to be giving public legal information. If you require legal advice, you’re going to have to have a privileged conversation with an attorney.

TFSR: With that said, as much as it’s useful to talk about, where are people in the US at with legal rights? What are the rights that people can expect to be able to assert, and who does that apply to?

Mo: The Constitution applies to everyone, whether or not police know that or care about that, or believe that it is it is true. The Constitution applies to everyone, and it applies to everyone, everywhere, sometimes in different ways. Notably, in certain institutions, like for example schools, prisons or borders, sometimes our rights are diminished. Sometimes the authority of law enforcement is enhanced. But the fact is that the Constitution applies to all people who are here, wherever they are. Now, if you’re somebody who’s particularly vulnerable, someone who’s not a citizen, someone who is a person of color, who’s gender non-compliant, disabled, etc. or if you are someone who is perceived to be any of those things by law enforcement, then I would say you need to be extra prepared, because you are someone who may be subject to particular scrutiny and targeted by law enforcement. If you’re traveling, then I would recommend that you be extra prepared and really understand what your rights are. If you’re someone who is known to the State because of your politics, then being extra prepared is helpful.

The fact is, of course, the law was created by human beings, and in particular by powerful human beings, in order to protect their interests. So the more layers of risk you bear, the more likely it is that you are going to be targeted, and that anything you do or say is going to be perceived in the least generous way. My first exhortation is not only to know what your rights are in an encounter with law enforcement, but to do your best to avoid encounters with law enforcement. The less time you spend in the company of law enforcement, the better. All of that being said, we all need to know how to invoke our rights, and we should all be investing in our legal education, connecting with legal resources and investing in good security practices. That’s not just to protect ourselves, but to protect the people around us. Anyone can get arrested at any time, for any reason or no reason at all. Your innocence will not protect you, but it’s a good start. We are in this age of rampant State repression, but we do still have all of these rights and being confident in exercising them, and especially, again, your right not to make statements to law enforcement or answer questions is key to resisting that repression.

TFSR: So the term State repression has come up a couple of times. Could you talk a bit about the idea of State repression, like the definition that you’re working from when you’re using that?

Mo: What I mean when I say State repression, is I’m referring to the use of the State’s power to target, harass, punish or undermine any activities, ideas, people or groups perceived as being a threat to State power. That can be by the use of the law, or it can be extra legal. It can just be harassment, or it can be through an actual prosecution. When we’re talking about State repression, it’s really important to make clear that the State’s perception of threat can be a result of actual conduct that people are engaging in, including conduct that’s completely lawful and protected by the Constitution. The State’s perception of threat can also be based on nothing more than its perception about an individual or group’s identity. So when I say this, one of the things I want to make clear is you don’t have to be doing anything illegal. You don’t have to be doing anything effective, and you don’t have to be doing anything at all to be subject to State repression. This is particularly true around the policing of criminalized identities, meaning your identity or your perceived identity, as opposed to unlawful conduct, is being targeted, policed or punished. It’s also true around criminalized behavior, meaning attempts to target behavior or conduct that is lawful but is viewed as undesirable, immoral or antagonistic to the interests of the State in some way. I am not going to suggest that you change your behavior or conceal your identity, but I want people to understand what they might expect and how to be prepared with the best possible tools to weather State repression.

TFSR: Can we talk about some specific implications of this in terms of identity or activities?

Mo: People often say, “Well, what about the First Amendment?” I’ve been arrested, but I was doing something that I’m sure is protected by the First Amendment. Yes, that is a thing that happens. There is a lot of repression on the basis of First Amendment protected political beliefs, activities, assembly and First Amendment protected identity. It is not new and it’s not unusual. The biggest misapprehension that I encounter about the First Amendment is this: The First Amendment protects our rights to political and religious belief, expression and association. It also protects our rights to any expression, including identity expression. The way we dress, what we look like, things like that. But the First Amendment does not immunize us from prosecution for otherwise unlawful conduct. What I mean by that is graffiti does not acquire First Amendment protection because it bears a political message. But importantly, with the exception of so called hate crimes, graffiti cannot be more illegal based on its content or viewpoint. So graffiti that says, “down with fascism” can’t be more illegal than graffiti that says, “hooray for fascism.” Now obviously selective enforcement happens informally at every level of the system, and is in fact discriminatory on the basis of First Amendment protected content, viewpoint and identity.

Throughout any conversation about law and rights in this legal framework of having human rights or having constitutional rights, it’s really important to recognize, again, the difference between the law as it’s written, the law as it is enforced, and the law as it is interpreted in court. Again, the de facto reality is people who are inclined to call the police are more likely to target predictable groups. Police, prosecutors and judges are more likely to take seriously conduct that’s alleged to have been done by certain people or motivated by certain beliefs, and they’re less likely to take seriously conduct, however harmful, however illegal, that is alleged to have been carried out by more powerful people or in the service of beliefs that are not viewed as antagonistic to State interests. I think I said before, anybody can be arrested at any time for any reason or no reason at all. That’s really scary and people do absolutely get arrested and prosecuted on the basis of their First Amendment protected beliefs, expression, association and identity. Nevertheless, it remains, actually pretty hard to bring targeted prosecutions only on the basis of these protected categories. In order to do that, you really have to strip away the traditional protections that are afforded to speech and identity, and those are actually pretty strong. So even though the State keeps trying to do that, and even though they have put in place practices that can accomplish this in some ways( for example, this is what has happened with hate crimes legislation) the law surrounding the First Amendment hasn’t actually changed all that significantly. Still, you can be arrested on the basis of these activities or as a result of engaging in these activities.

Police certainly violate the First Amendment routinely, but it does make it much harder to sustain a prosecution or obtain a conviction. If that First Amendment violation really is the only basis of an arrest, it doesn’t undo the damage that can be done by an arrest, certainly for people for whom an arrest has other consequences. For People who aren’t citizens, an arrest is going to affect them much more severely. For people who have certain kinds of educational or medical licenses that the State can withdraw on the basis of an arrest or a conviction, an arrest might affect them much more severely. Someone who’s on probation or who has an ongoing child custody dispute. There are all kinds of ways that the arrest itself could be really harmful. But it is very difficult to maintain a prosecution or to successfully prosecute what is actually protected behavior. Which, of course, is not to say that it isn’t wildly disruptive to individuals, communities and movements to have that happen. The law itself certainly does not constrain the ability of police to make those arrests or the ability of prosecutors to try to pursue those prosecutions, but they are often not really supported by the law.

TFSR: That makes a lot of sense and is super disruptive, as you said. People lose their jobs, people lose their housing, just based on an arrest without a conviction. Then if a conviction does go through (because some local, circuit, State Supreme Court or whatever, finds in support of the prosecution) and a Federal Constitutional Court decides actually that shouldn’t have stood, the person still has to go through all of this time and resources fighting this, as opposed to the resources that the State has in order to prosecute.

Mo: I’m really not trying to say, “Oh, this isn’t a problem. The law supports you. It’s not that scary. It’s not disruptive.” It is horrendously disruptive and everything you said about all of the time, energy and resources is absolutely true, which, frankly, is one of the reasons that bringing prosecutions and making arrests is such an effective tactic for the State. It really drains our resources and attention. It really refocuses all our energy away from doing actual movement work to doing things like court support. The actual message gets lost in the sauce of all of this legal process. I certainly don’t want to diminish the gravity of that, but it isn’t new. It isn’t unusual. We have always seen activities that are protected by the First Amendment be punished by arrest and prosecution. We have always seen police violence. What varies by time, the historical moment and jurisdiction, is the degree to which that happens and the severity of it.

In New York City, where I mostly practice, I’ve seen this. The use of force, the use of prosecutions, the kinds of charges that get brought. I’ve seen those go up and down over the years and over time, the typical practice has generally been cops use mass arrest as a form of crowd control without anyone outside of the cops seeming all that interested in really vigorously prosecuting most of those arrests. That has changed from time to time. Sometimes we see a lot more violence in this kind of policing, especially where we have anti-police brutality protests and the cops are basically showing up as counter-demonstrators. We certainly see a lot more violence. We see a lot more serious charges being brought. That goes up and down depending on the kind of protest it is, how those protesters are perceived, what the policies are of the federal government, the local government and the local district attorney’s office. Right now we’re in a moment where totally garden variety protest behavior is being charged more seriously and prosecuted more vigorously than I have seen before in New York. Again, what’s defined as First Amendment behavior by prosecutors, or what’s legible to cops and prosecutors as being First Amendment protected is going to be different depending on, for example, if you’re talking about a textbook Martin Luther King style sit in where everyone has a sign, or a group of Black youth congregating for any reason. Both of those things are equally protected by the First Amendment but this is where the difference between law and law enforcement really comes into play. The cops are charged with sort of enforcing their vision of public order and their individual visions of public order may or may not have anything to do with the Constitution.

TFSR: So recognizing that repression is ramping up right now, and recognizing a framework of rights and risks, let’s talk about what we can do. These are scary times, but a very important time for people to be speaking up in their own defense, or in defense of their communities, or the communities of their neighbors and loved ones. So can we talk a little bit about what do we do with this Know Your Rights and security framework?

Mo: First of all, one of the things I always try to say to people is that we don’t need to do law enforcement’s job for them. Invoking your rights really matters. I know that it’s very frustrating, because the effect of invoking your rights isn’t something that takes place in real time. If you say to a police officer, “I’m not consenting to a search,” it doesn’t magically make them not search you. It does something to the kinds of arguments that are available for an attorney to make in front of a judge, many months down the road. I know that’s really frustrating, but the fact is that it’s a way of maintaining your own power, and of not painting yourself into a corner where you end up producing evidence that the State can use against you to punish you. So being prepared and not being discouraged and understanding that this is a really long game, are all really critical parts of this. It really matters. As I said, avoiding encounters with law enforcement is something that I vigorously recommend. In the event that you have an encounter with law enforcement, knowing how to invoke your rights is pretty important. Like I say a lot to my clients, I understand that they feel totally justified grief and rage about the variety of genocidal violence that are being enacted by the State. I share this grief and rage. I understand the impulse to smash the State, but the fact is that there are a lot of times, especially for people who are members of more vulnerable groups, where maybe avoiding the State is really the move. That doesn’t mean we do nothing, right? Maybe that means we do mutual aid and jail support and infrastructure building. Again, is that guaranteed to keep you away from ever having contact with law enforcement? No, but it can help.

Look, I’m not your dad. I’m not here to tell you not to protest and not to do civil disobedience or direct action. If that’s the thing that you are moved to do, then I want you to feel empowered to do that. Also, I want to remind you that none of the things I just mentioned are necessarily actually illegal. They are just things that may bring you to the attention of the State. Everyone should be cultivating good security practices, not because that’s how you get away with crimes, but because you’re entitled to privacy. The State is just not actually entitled to your private information, and the State will often use that information (which, again, is completely innocuous, constitutionally protected information) to manufacture or support politically motivated but unwarranted investigations and prosecutions.

You don’t have to be doing anything illegal to be subject to State repression. We should all be aware of that and be circumspect in how we move through the world. That does not mean self-censorship. It does not mean hiding under the bed. It means being thoughtful about what we say, where we say it, who we say it to and making sure that we’re really engaged in the calculus of what is our end game, what are our political goals and do these strategies move the needle on those goals? How much punishment, how much legal intervention are we able to tolerate in the service of our goals? That is something that’s a calculation that I as a lawyer absolutely cannot do for anyone else. But what I can say is I want you all to be thinking about whether the thing that you’re planning actually is going to be useful. Is it actually going to accomplish what you want it to accomplish, or is it something that’s going to be spectacular and dangerous to you without accomplishing the thing that you’re trying to accomplish?

TFSR: One term that floats around in response to repression is security, which sometimes people use to describe practices around different technologies. It’s pretty frequent that I hear “Oh, security? Well, don’t bring your phone.” But in addition to digital security (which is just one element, representative of strategy or a way of thinking, as opposed to a set of specific practices) what sort of security culture do you propose that people engage?

Mo: That’s going to look different depending on what communities you’re in and what you’re doing. I would reiterate State repression is often not in response to unlawful conduct. There’s a real anxiety about even talking about security sometimes, because there’s been a lot of propaganda that has educated people to see the idea of security as a code word for how to do crimes. Again, you have rights to privacy. We have curtains on our windows. We have doors on our bathrooms. Nobody thinks that you’re doing anything illegal, because you close your curtains sometimes. There’s just information that the State is not entitled to, and you have no obligation to share information with the State. Doing so again can be very dangerous, even if you haven’t done anything illegal. State repression exists all the time. It’s a whole apparatus. It exists even when we can’t see it, and that’s really scary. In fact, one of the most powerful tools at the State’s disposal is fear. Fear is really chilling to action and speech. It can even prevent social movements from getting off the ground entirely. The solution to these efforts to frighten you into silence is not self-censorship. It’s courage.

I have observed a lot of defeatism about security where people are like, “Oh, the State just knows everything we do. So why would I even bother?” Then I’ve also observed a lot of sort of blithe technicism, where people are like, “Well, I use Signal so nobody else could ever know what I’m up to.” You know your Signal messages are not encrypted to your eyes. If somebody gets your phone, they can read your messages. What I would say is security is a set of practices, not a set of technologies. A lot of times, people are so wrapped up in digital security tools, that they forget that electronic surveillance is prevalent, but not all surveillance is electronic. Is it important to use disappearing messages? Yes. Is it also the case that your group chat is only as secure as its participants and all of their phones also? Yes.

You cannot live your life mistrusting everyone and looking over your shoulder. It is not useful to play “Who’s the Cop in the Group Chat.” But also, you have to be able to be in community with people who know how to exercise discretion and whose actual behavior (whether or not you think they’re being paid by the feds) is not dangerous to the people around them. Again, I’m not saying “oh, cancel people who have bad security practices” or “cancel people with problematic beliefs.” I just don’t think that gets us anywhere good. This is information. Maybe people who are engaging in behaviors or practices that are troubling, are not people who have access to sensitive information. Maybe these are folks who get a little bit of extra care or support in terms of addressing whatever the conduct is that’s dangerous or potentially disruptive. For example, Food Not Bombs is just transparently, the same kind of First Amendment protected voluntary association as a church bake sale. If you get someone who’s showing up to Food Not Bombs and advocating for it to be Food and Bombs, maybe there is a conversation that happens there about community goals. If you get someone showing up to a space where their values are inconsistent with the shared values of the group, (like maybe they want to exclude certain groups, or they want to use certain tactics, maybe they want to share information with the public or with police) that’s a conversation that you have. There might be a role for that person in a larger community or even in a movement, but it might not be with your group, or it might not be in the particular role that they want to be in at that moment. That’s not because you’re sneakily concealing your crimes from this person. It’s because literally anything you say can and will be used against you. So if there is somebody around who doesn’t share your values, particularly maybe who doesn’t share your values around talking to cops, that is not necessarily someone that you are compelled to organize with.

TFSR: As you point to, having a conversation is an important thing, and that’s a step that is uncomfortable. A lot of people avoid that as a part of their community security practice. If we have a disagreement, it’s possible that somebody doesn’t understand the implications or the concerns of the other people in the group as to why that would be inappropriate or just activated around a certain issue. Having this conversation, working out conflicts doesn’t have to be a resolution, necessarily, but this is good practice. Oftentimes it seems like preexisting conflicts can be a good point for the State or other outside groups that are trying to break up movements or cause disruption to take advantage of.

Mo: Absolutely. I will say, I think the greatest tragedy of COINTELPRO, where the FBI manufactured conflict in social movements (and they did so using the entirely First Amendment protected conduct, association and expression of these groups) to great effect. The tragedy there is that it did, in fact, give people in social movements a lot of really good reasons to mistrust other people in their movements. So now, things that are personality conflicts or ideological differences, can be parlayed into these massive, explosive movement ending conflicts. If we can have direct communication with each other and approach each other with a spirit of curiosity, as opposed to censure, and where people have the space to be able to change their minds and say, “Wow, I really never thought about it that way. I’ve really learned something,” that’s going to make our movements much stronger than this thing that I have observed over many years where people just get ostracized. There are sometimes times to say, “Look, we’re not going to mess with this person. This person is no longer welcome” sure. But our goal should be to be in conversation, to be mutually supportive, to recognize that it’s okay to have unresolved conflicts. It’s okay, especially as individuals to say “Yeah, I actually am just not comfortable organizing with that person” and walking away from something, and that’s fine. I don’t think anyone needs to feel any type of way about saying I’m just not comfortable with this person for any reason or no reason at all.

But I would love to see movement spaces where people do have the space to change their minds, to learn things, to become better people. I am so grateful to all the people that I’ve been in community with over the last 25 years who have pulled me aside and said, Hey, you said something that I think wasn’t very thoughtful or like, I’d like you to think about how this thing, you know, your proposal, could affect this group of people, right? That’s how we become better people. We’re not going to become worse people. For seriously, you know, giving air space to good faith criticism, I think that that’s like kind of underlying security culture in a lot of ways. Is that openness.

TFSR: Yeah, it seems for trust to exist and for people to take risks together, there needs to be affinity. There needs to be understanding, not that everyone has to agree on everything, necessarily, but having those like set like we agree on these things and we don’t agree on significant enough stuff that we can work together is kind of the the like mathematics that I make of like, if I have trust, if I have affinity with someone else in you know, enough to act and organize with them.

So, we’ve been dancing around it. Let’s talk about, know, your rights, or Kyr, as it sometimes gets short handed in in movement spaces when you’re giving a presentation or when you’re talking to people about just framing out the rights that they should consider engaging when they are forced to interact with law enforcement. Can you give us, like, a sort of outline and talk about some of those?

Mo: Yeah, I’ll give you the quick and dirty. So in a general way, whether or not you have done anything illegal, whether or not you’re somebody who you know is concerned about prosecution, if you have an encounter with law enforcement just as a matter of solidarity, as well as being a matter of safety, I would really recommend that people invoke their rights not again, because it will constrain the behavior of law enforcement in Real Time, because it almost certainly will not but because A, if you’re arrested or if your civil rights are violated, it’ll help your lawyer make certain arguments that will not be available if you did not invoke your rights. And B, it’s really good for community solidarity for the cops to know that your community is aware of what their rights are.

So there’s a lot of caveats here, and I’m going to say absolutely, fundamentally, you should always do what feels safest to you. But I would also say that verbally invoking your rights in any encounter with law enforcement is preferable. And I would say like I’m about to give you a very abbreviated outline of how to invoke your rights, but I would really encourage anyone listening to engage in Know Your Rights or Know Your Risks trainings that have role play and that are put together by attorneys and legal workers who are really familiar with your local jurisdiction, because I don’t think there’s really any substitute for that.

If you’re approached by law enforcement, you can ask, “Am I being detained, or am I free to go?” If you’re being detained, ask “Why?”, and if you’re free to go, go. If they ask for ID, honestly, it’s probably expedient either to just tell them who you are, or to give them ID. It’s expedient first of all, because it can mean that you’re spending less time with them, because sometimes if you don’t give them ID, they can use it as an excuse to arrest you and then hold you until they figure out who you are. And frankly, in my opinion, the less time you spend in the company of law enforcement, the better. But again, you should always do what feels safest. In some states, it is its own crime to refuse to identify yourself. So again, I would say, if you are able to do it, giving them ID can be expedient because in some states it’s a crime, and in some states it isn’t. I am encouraging everyone listening to do a Know Your Risks or Know Your Rights training that’s carried out by people who are really familiar with what the law is where you physically are, geographically. You can find Know Your Risks / Know Your Rights trainings, they’re done by the National Lawyers Guild, the ACLU, a lot of local law schools will do them. Sometimes even libraries will do them. And if you really are not able to find one, you can call the NLG national office, or you can call the hotline, and we can try to help you identify some people who might be close to you or available or able to do and Know Your Risks for you.

So if you are being detained, cops are allowed to pat you down, over your clothes, to search for weapons if they have what’s called a quote, a reasonable fear for their safety. Who gets to define the word reasonable?

TFSR: The cops!

Mo: The cops! But if they’re looking for a weapon, they really kind of can’t look in your wallet, right? If they’re looking for a handgun, they can’t look in your pack of cigarettes, right? And no matter what, if a cop is about to pat you down or search you, you know. You don’t know, and frankly, neither does the cop, whether it is going to be a lawful search, unless you consent to the search, and so you don’t want to consent to any searches, right? If you’re about to be patted down or searched, you can say, I do not consent to any searches. I want to be clear. People will go, “Well, I don’t care if they search me, because I don’t have anything illegal on me.” Well, look, if they pull something out of your pockets. I mean, we’re not just talking about, you know, LSD and fireworks. They can take something out of your pocket that’s like a little scrap of paper with someone’s address written on it and decide that that’s evidence that you are going to go burgle that address, right? We don’t know what they’re going to see as being evidence of a crime, and so not consenting to any searches means that if they do find something, and they do decide that it’s evidence of some kind, and you have said, “I don’t consent to this search”, your lawyer is able to argue to a judge that the prosecution shouldn’t be able to use anything they found in that search as evidence against you.

TFSR: And that’s the fruit of the poison tree. Idea is that, right?

Mo: Yes, that’s illegally obtained evidence can’t be used against you, right? But if you don’t say, “I don’t consent to a search”, then you are considered to have consented to the search.

TFSR: Fourth Amendment?

Mo: Yes, under the Fourth Amendment. So the Fourth Amendment protects you against unwarranted searches and seizures, but if you consent to those searches and seizures, then there’s no protection right. You’ve waived your protection. You’ve waived your right, and so the way that you make sure that you preserve that right is by saying, “I don’t consent to a search.” And you have to say it loud and clearly. And you know, as I’ll talk about in a second body-worn camera is pretty ubiquitous these days, so say it right into their chest where their body worn is.

If you’re arrested, we all know that there is a common practice among law enforcement to kneel on you such that you’re not able to put your hands behind her back and then to scream, stop resisting. If they are yelling at you to stop resisting because they are kneeling on you and have pinned your wrists under you, or in some other way, have made it impossible for you to “comply”, then you can say as clearly as possible, “I am not resisting. You are preventing me from complying”, and you can explain why, and hopefully that will be picked up by their body worn camera.

A fake thing that everyone thinks is true is that if you are arrested, the cops will read you your rights. Cops will not read you your rights. When you are arrested, they will not read you your rights, unless and until they are formally trying to interrogate you, but the second you are being detained or arrested, you can just say, “I am going to remain silent and I want to speak to a lawyer.” They’re going to ask you some questions like, “Who are you? Where do you live? What’s your phone number?” And it can be useful, truly, to disclose certain information that’s basically already known to the state, right? The State gave you your social security number. They already know what it is. I don’t think it’s like a huge problem for most people, particularly for citizens, to give that kind of information to police, and it can be pretty disruptive not to and it can cause. Some other problems down the line. Also, if you’re in custody, you should be advocating for the human dignity and medical needs of yourself and other people who are in custody. Right? If you need food or water to go to the bathroom, you should advocate for yourself or you should advocate for someone else. But after you say those things, re invoke your rights. Right you have if you say “I’m going to remain silent”, you have to then actually remain silent, or it doesn’t work.

There’s just no reason to talk to cops about anything. There is no reason to talk to cops about your politics. You’re not going to win them over. There’s no reason to talk to the cops about your friends or what you had for breakfast. Please, please understand when we say, anything you say can and will be used against you. That is an extremely accurate statement. Anything you say, anything you say in custody or out of custody, anything you say to police, anything you say to someone who’s in your cell, to journalists on the internet. For the love of all that is holy, remember that the phones in a lock up are monitored and recorded. If by some miracle you get a phone call, do not say anything other than that you have been arrested and where you are. When I say anything you say can and very much will be used against you, I am not being cute. I am being totally, totally serious. You have no obligation to cooperate with law enforcement or to answer their questions. Declining to answer their questions is not evidence of guilt. It is not a crime. It is not obstruction, whatever they may tell you, it is protected by the Constitution. Failing to exercise your rights, and in particular, failing to exercise your fifth amendment right not to talk to cops can be extremely dangerous to you and others.

I always have one person who thinks they’re really slick and that they can convince the police to let them go. I will tell you you are not going to talk yourself out of custody, but you absolutely can talk yourself into a conviction. There is never a reason to speak to law enforcement prior to speaking to a lawyer, your rights to protest, your rights to remain free of unwarranted searches and seizures, to remain silent and to talk to a lawyer are protected by the Constitution, and so all you have to say is, “I’m going to remain silent, and I want to speak to a lawyer.”

TFSR: Quick follow up question to something that was said earlier: When I was doing cop watching California. The way that lawyers explained it to me was that with identifying yourself like obviously to shorten the length of the interaction. So say that you ask cop like, “Hey, am I being detained? Am I free to go” and the cops like, I’m detaining you right now? And you ask, “Okay, what’s the probable cause? Whatever a reasonable suspicion?”, excuse me. Okay, well, the reasonable suspicion is that you can, they can give a reason, and maybe that differs from the reason that they give later when they process the paperwork if you get arrested, and so that’s a good way to potentially help a lawyer get you out of a circumstance.

But part of the purpose of identifying yourself, if it’s not just like a legal requisite. That the logic that’s argued, is that if you’re given a ticket or a summons or something like that part of it is going to be to be able to send a ticket to an address to be able to reach you. It doesn’t have to be necessarily your address, but just an address that you could be reached at at some point the future. And part of the identification thing is to make sure that you’re not currently being sought by law enforcement. There’s not a warrant out for your arrest.

Mo: I would say a good rule of thumb is to give them as little information as possible. And at the same time, one thing I know just from sort of practice, from practicing as an attorney, is that refusing to give them information like you know that you have a job and that you have a phone number can be used as a rationale to claim that you’re a flight risk. You know, again, I’m going to make a real, heartfelt plea to everyone listening to go and do a real Know Your Risks / Know Your Rights, training with people who practice wherever you are actually located, because those are the exact kind of nitpicky questions that I’m just not in a position to answer, and somebody who really practices in your jurisdiction is going to be able to answer.

TFSR: Okay. The other follow up that I had was: We talked about detention like, you’re detained, here’s the reasonable suspicion of you being involved in a crime to detain you about. Until you get word that you’re actually being arrested, does it make sense to keep asking “Cool, am I free to go now? Am I being detained?”

Mo: Yeah, for sure. And like, I think it’s important again to say, do it feel safe? You know, obviously, if you do have a warrant out for your arrest, your calculus might be a little bit different. You know, I can’t make that decision for you. If you’re someone who doesn’t have ID, if you’re somebody who entered the country without inspection, these are things that would be really specific risk factor. I would really want you to not have any encounters with law enforcement, but where I would hope that you’ve had a private, privileged conversation with an attorney about how to deal with that.

TFSR: Yeah, and I just want to intercede here and say that I think that as an anti-state movement, as an anarchist culture: we’ve gotten very good at spreading the message ACAB (All Cops Are Bastards) right? People just don’t like the cops, hate the cops, [are] rude to the cops. Whatever that is, even though there’s sass-back charges [you can get] in some civilized places like New York. I think that ACAB is a good starting point but if, and this is why I was excited to have this conversation with you, ACAB isn’t enough. And if we’re just like bad mouthing the cops, making up stories, trying to confuse them, doing whatever in our interactions, rather than avoiding them completely, then we we allow ourselves to walk into traps that they either have set or are planning on setting, with whatever testimony we give them in the meantime. Those conversations are interviews. Anytime a cop is talking to you, besides getting that basic information or giving you some sort of orders, considered that an interview that you can end at any time with I’m going to remain silent. I want to talk to an attorney.” “Am I still being detained? Am I free to go?” Right?

Mo: Yeah. I mean, in addition to creating the danger of retaliation, talking to cops, arguing with cops, this is a losing battle. You know, they have guns. I mean, you’re I know there’s a lot of TikToks where people are very funny in their interactions with cops. And that’s as satisfying for me to watch as anyone, but I would just say: the less said, the better. Not creating evidence that can be used against you is a good move, and I can’t even explain how when we see people invoke their rights and an attorney does call and says, “What do you want with my client”, I would say an overwhelming majority of the time, that’s the end of it. And when we see somebody sort of go off on the cops or start to try to explain themselves, all of that verbiage ends up being used against them. That’s where we see search warrants being obtained. That’s where we see arrest warrants being obtained. Because anything you say, including things like, “I didn’t do it”, can be used against you.

TFSR: You said that constitutional rights apply to everyone present [in this country]. It doesn’t necessarily matter: everyone has rights, whether they’re prisoners, whether they’re not citizens, citizens, kids, whatever. But you also mentioned that there are circumstances where there are caveats, where these rights might be changed because of some legal circumstances. So I wonder if you could talk about some of these sorts of situations, parole, probation, children, etc.

Mo: So the thing is that within our framework of constitutional rights, your rights remain essentially the same, but there are different ways that they might come into play in different situations. And there’s different ways that they might be diminished in certain situations. It is still worth invoking your rights, even if it turns out that a judge later says, “No, this was a lawful search”, or, you know, “the cops were allowed to kick in your door”, it doesn’t do any harm for you to have invoked your right not to be searched, right?

So, some of the special circumstances that are worth touching on so if you’re on parole or probation, you already know what your conditions are, and that your PO can come to your home whenever they want, basically, and search your house and pat you down and look in your pockets and, you know, give you a piss test or a blood test or whatever. Forever. And folks who live with you probably also know that their common space might be invaded, right? The living room, your shared bedroom, your refrigerator. But people who are in a situation like that typically already are pretty acutely aware of all the ways that their rights to privacy have been diminished. Apart from situations like that, there’s other situations where people actually think that they have fewer rights than they do. Children have all the same constitutional rights as adults and are allowed to have a parent or guardian present with them if they’re being interrogated. For example, there are some diminished protections at places like schools, sometimes regarding searches, but kids still have first amendment rights to expression. They still have Fifth Amendment rights not to answer questions, even if their parent or guardian is present with them.

A big place where our rights get a little muddy is vehicle stops. Cops can search anything that’s in your car, if it’s within arm’s reach. They can search your trunk and anything that’s locked up in your car, if they have a reasonable suspicion that they need to. This is defined in somewhat different ways, all of which are subject to control by the cops. So, again, this is in a vehicle stop. This is a place where, as long as you feel safe, you can say, “I do not consent to this search.” Are they going to search you anyway? Probably, but at least then you won’t have just consented to the search. The big one really, is borders, international borders. You know, this is another place where security becomes really important, because you do have rights at the borders, but especially for like international travel, those rights can get diminished and trampled upon. So for international flights, they can seize or copy your devices, but very importantly, they can’t make you give them your passphrase. So I’m going to say that again. They can’t make you disclose your passphrase. You know what they can do. They can take your finger and stick it on the fingerprint reader. They can wave your phone in front of your face and unlock it with facial recognition. But if you have a strong alphanumeric passphrase, it’s going to be much more difficult for them to get into your phone, because you cannot be compelled to disclose it, right?

You have a fifth amendment right not to talk to cops, and that includes not disclosing your passwords. So one thing to remember is your smart watch. If that thing is synced to your phone and it’s not secured and encrypted, they can just go through that. Really the best practice here is to just have really good digital hygiene if you’re doing international travel, and not be traveling with anything that you don’t want cops to see. Again, things that you don’t want cops to look at, is not code for illegal stuff. I mean things that are private, things the state’s not entitled to: your contact lists, your nudes, your political musing. These are all squarely protected by the First Amendment, but can be used in really sinister ways by the state for things like social mapping, infiltration, sewing discord, and we don’t need to give the state access to that material. It’s just none of their business. I want to refer everyone to a zine called “At The Threshold of Empire” that was put out by Austin ABC. There’s a lot more detailed information about this, and bursa can send it to you if you don’t already have it, and maybe you can upload it to your show notes.

TFSR: Well, I guess [I have an additional] two things [to ask about] and I want to go back to borders a little bit. But if you’re on parole or probation, and you’re riding in a car that gets pulled over, ostensibly, maybe the cop claims that there’s a light out or something. Whether that’s true or not, they decide to pull over the car does something that is in the possession of somebody else that’s in the car. Can that become a danger to you?

Mo: What I can say is any encounter with law enforcement for a person on parole or probation is potentially disastrous for any reason, right? Even if it’s completely by chance, there’s just not a way for me, from this vantage point, to answer that question in any kind of specific way. But certainly anytime a person who is already subject to that kind of state intrusion has a separate encounter with law enforcement, it’s a very high risk situation for that person.

TFSR: A question about borders… So in 2020 we saw the deployment of customs and border patrol officers into Portland, which is within 100 miles of the coast, which is considered a border. Does being within 100 miles of a border change generally your reasonable expectation of rights with law enforcement? Or does it depend that you’re going to be more more likely in interaction with federal law enforcement, enforcement who do Border Patrol, like in international airports within 100 miles of the border. And also, and this is a weird thing, and I could cut it, but like international trade zones that are within the US.

Mo: So here’s what I’ll say. We talk about the border like the border is this physical, geographic location. And we talk about this 100 miles, you know, “within 100 miles of the border”, like the relevant thing is the geography. The relevant thing about borders is not the geography. It is the individuals who are being policed and whether they are perceived as being on the right side or the wrong side of that border. And so when we talk about borders, I think it’s really important to remember that the border is actually cited, really in the bodies of the individuals who are being policed. For people who are United States citizens and who are perceived as being United States citizens by law enforcement or by Border Patrol, I don’t think those people are at a lot of risk for being policed differently or for having their rights being interpreted differently. I think the place this becomes relevant is the way that people are being targeted for certain kinds of specific action by border control in places where Border Patrol knows they can get away with certain kinds of policing. And that later it makes it much more difficult to challenge rights violations by specific individuals, because Border Patrol can say, or the government can say, “Well, they were within 100 miles of a border, and so that kind of intrusion was warranted or was justified and was lawful, right?”

I think it is really important to talk about the rights of non-citizens. So I want to say, first, [that] I am not an expert in this particular area, but my absolutely devastatingly brilliant colleagues over at CUNY CLEAR very much are. And I cannot recommend strongly enough that anyone who is not a citizen, whether you have status or not, whatever your status is, and honestly, everyone, but particularly people who are not citizens, get familiar with the materials that have been created by CUNY CLEAR and that are available on their Instagram, which is at @CUNY_CLEAR. There are Know Your Rights resources and guidance about everything from travel to charitable contributions to protesting as a non-citizen. And they have these resources in English, Spanish, Arabic, Bangla, Urdu and Farsi.

So the first thing I’ll say is, if you have an immigration case already, you need to get specific legal advice that is responsive to your specific circumstances, as opposed to general information before you travel. There is not going to be a substitute. You cannot substitute a zine for specific legal advice if you already have an immigration case. For anyone else, you should know that they might question you about things like where you’re going and why and how long you’re staying. And those are questions that are within the ambit of Border Patrol’s authority to ask, and you can answer those truthfully, but the sort of general wisdom is don’t give them anything they don’t ask for. As I said, even non-citizens have constitutional rights, and they have those rights even at the border. So if Border Patrol starts asking about your religion or your politics or whether you know certain people, that is a First Amendment violation. They do not have the right to ask you those things, and you don’t have to answer. You can just say, “I’m not comfortable answering that.” And just in the exact same way that regular cops might try to imply that your refusal to answer questions is evidence of guilt or a reason to arrest you, the cops in the airport or at the border might imply that they can detain you. Now, look, I’m not going to tell you that they won’t detain you, but they cannot lawfully detain you for refusing to answer those kinds of non-travel related questions about First Amendment protected subjects. That’s sort of the the TLDR, but I would just really encourage everyone listening to check out that outstanding resources that have been put together by CUNY CLEAR.

TFSR: You’ve described like the rights that people have if they’re pulled over by police or if they interact with police. What about federal agents? How is it different?

Mo: You don’t have to talk to them, either! Listen, federal agents approach people who are not in custody to see if they will voluntarily speak with them, and they are very often doing this precisely because they don’t actually have a reason to believe that any Federal offense has occurred, and therefore they do not have a warrant that would allow them to access your home or place you under arrest. And that means they don’t have the kind of information they need that would allow them to ask a judge for a warrant. You know how they go about getting that information, whether or not you’re actually doing any crimes, whether or not any crime is happening at all? The way that law enforcement gathers the information that they will use to go and get a warrant to justify further intrusions and further searches and potentially prosecutions, is by convincing people to voluntarily speak with them. But you don’t have to do that.

TFSR: What do you do if law enforcement shows up at your door?

Mo: Again, you don’t have to speak with them, and if they don’t have a warrant, you don’t have to let them into your home. That means that you can try to speak to them through the door or through the intercom. But I’m going to be real with you: If federal agents show up and they do have a warrant, I don’t think it’s very likely that you’re going to have an opportunity to ask them if they have a warrant, or to ask them to look at their warrant before they come through your door. But if they show up, ask “Who’s there?” Ask what kind of agents they are. Ask if they have a warrant. If they do not have a warrant, you do not have to open your door, and if you do, they will use that as an opportunity to come inside. So if you don’t want them to come inside, the best bet is to speak to them through the door or through the intercom, and not to open the door to them even a little bit. They’ll take that as consent to come into your home, and anything that is in plain view in your home can be used as evidence against you. If they have an arrest warrant, call an attorney immediately. If you’re able to go outside, close the door behind you again so that they can’t come in. If they do have a search warrant, and you have the opportunity to take a look at it, ask them to slide it under the door and back up from the door, just in case they come through it, and read it out loud, so that they know that you know what they’re allowed to look for. If they’re looking for a Volkswagen, they can look in your garage, but they can’t look in your phone. So again, I know that it’s really hard to remember what you’re supposed to say or what is safe to say to law enforcement. That’s why I’m going to give you a document that you can upload to the show notes, and folks can print out and tape to the back of their door, and then they can just read from it if they need to.

TFSR: And okay, so you mentioned that if they’re looking for a Volkswagen, they’re not going to be looking in your phone, so you read the thing back to them what information is pertinent to know and to verify on the on the warrant. Like the date, right is one thing?

Mo: Yeah, the date, what time it is, you know, when they’re at your door, was signed by a judge, and what they’re allowed to be looking for, and what if anything, they’re allowed to, you know, take away.

TFSR: And sometimes I mean the address too, right? As one thing, like,

Mo: Yes, you want to make sure they’re in the right place, because they aren’t always,

TFSR: And you’ll be lucky if they don’t just come in blazing and apologize afterwards or something.

Mo: I mean, frankly, there’s a reason I said that I’m not sure if they have a warrant that you’re going to get a real opportunity to to ask them to slide it under the door, because by the time that happens, you may not have a door left to slide it under.

TFSR: Obviously we don’t need to be living in fear all the time, but I’ve heard of cases where people’s houses have gotten busted into or searched and there were unencrypted devices around that had information on them that people might not want the cops to have, despite the fact that it’s not necessarily illegal material. Would you consider it good practice for people start thinking about encrypting their devices, keeping them in an off state, if they’re not using them, that sort of stuff?

Mo: I mean, this is one of the aspects of security: understanding that not everything that is private illegal, but you don’t necessarily want the police to have access to your nudes. I mean, I’ve actually heard some real horror stories about police accessing people’s phones and making comments about or otherwise making it known that they looked at people’s intimate photos, and that’s just sort of horrifying. There’s nothing unlawful about having nudes on your phone, but certainly I can imagine many things on our devices that we don’t necessarily want you know, including things like medical information that we just don’t necessarily want to be available to law enforcement. And people should understand. A warrant really does have to describe with specificity what they’re looking for. And so if you live in a house where you have five roommates and you just rent a room there, it’s worth talking to your roommates about having locks on all the doors and labeling whose room is whose. Just so that people who aren’t actually contemplated by the warrant don’t end up having their phones taken, which is absolutely a thing that happens, particularly with shared housing.

TFSR: What about if ICE is showing up, assuming you get the chance to have the conversation with them, what do they have to produce to legally get access to to your space?

Mo: Yeah, so a warrant, a valid warrant for immigration, has to be signed by a judge. And there are these things called “ICE warrants” that are basically fake warrants that ICE agents will just show people. I would really, again, recommend that you take a look at the CUNY CLEAR resources and other resources that I can send to you and you can upload to the show notes that do like a side by side comparison of an ice warrant with what’s called a judicial warrant, or a warrant that actually is signed by a judge. An ICE warrant just does not have the same legal effect. If they show up to your place with an ICE warrant, you don’t have to let them in. If they show up with a judicial warrant, that’s a different situation, but a really vast majority of the time they don’t have a judicial warrant.

TFSR: But this sort of circumstance is extra scary for people that are stopped in a vehicle. There’s tons of videos on Tiktok and Instagram of people that are getting stopped by law enforcement who don’t identify themselves and maybe blocked into their vehicle and windows busted out, with people get taken.

Mo: Look, again, this is the this is a place where the law itself does not constrain the behavior of law enforcement. And I certainly don’t want to encourage people not to leave their homes. I don’t want to tell people, “Oh, you have to go into hiding and never say anything and, you know, hide under the bed and mistrust everybody.” Which is why I’m saying that the law does not, is not going to keep you safe in real time. It’s not going to mean that you don’t get searched. It’s not going to mean you don’t get arrested. But the way that you respond, the way that you’re able to say, “I’m invoking my rights”, that can be significant once you actually get in front of a judge, right? And what I have seen, at least, you know, in a sort of overarching way, what I have seen is that judges have been upholding precedent and making decisions that are pretty consistent with our the understanding that we have long had of what our rights actually are.

TFSR: So if the judge has a flag that has a fringe around the outside of it, in the courtroom…

[both laugh]

I had to make one Sovereign Citizen joke…

Mo: Oh, man, all right. Yeah, that means that if you hand them your social security card and renounce your citizenship, you can just walk out… Man, it’s the cheat code.

TFSR: So let’s talk a little bit about grand juries. What is a grand jury? And how should people interact with them?

Mo: Yeah, well, the first thing I’ll say is, if anyone gets something that says the word subpoena on it, I’m just going to encourage you to call the NLG hotline immediately at 212-679-2811.

I’m not going to get super in the weeds about federal grand juries here today, but basically, there are some very unusual things about federal grand juries that make them really powerful tools for disrupting social movements and punishing political people. And because they’re so unusual, there’s not actually that many people who have a lot of experience dealing with them in court. And I think it’s a place where you’re really going to want somebody who has that kind of unique expertise. So I will really encourage anyone who gets something that says subpoena to call that hotline at 212-679-2811, so that we can help to connect you with people who really have that kind of experience and expertise.

TFSR: Great. And if somebody wants a, you know, a listen through it looks like episode 44 of season one of Live Like The World Is Dying. You talked to Margaret killjoy about the subject. It’s a good chat.

Mo: Yeah, it was a fun chat to have. It’s always nice to talk to Margaret.

So okay, so I don’t want to get too in the weeds with this, but I do want to tell you briefly a little bit about federal grand juries, if you have a minute…

TFSR: Yeah, absolutely.

Mo: Okay. So a federal grand jury is just the process by which a federal prosecutor presents evidence to a group of 18 to 24 people who have been called for grand jury duty in the same way that we get called for regular jury duty. And that group of 18 to 24 people determines whether there’s been a federal offense, and they give the prosecutor permission, or very, very rarely, deny the prosecutor permission to bring federal charges against somebody. Obviously, the whole criminal legal system is a political system, but not every federal grand jury is explicitly politically motivated, or could be credibly characterized as an abuse of prosecutorial power. But where a federal grand jury is politically motivated, there are these special characteristics of a federal grand jury, which is just this legal process, that make them powerful tools for disrupting movements, while also insulating them from accountability.

And so I’m going to tell you very quickly why they’re weird. Basically, unlike every other proceeding in the US legal system. Grand juries happen in secret: very importantly, the witness themselves, the person who has been given a grand jury subpoena, is allowed to talk about their own experience. So if you do get a subpoena, you are allowed to tell people all about it, and honestly, in the interest of making sure that you aren’t isolated, I am a big proponent of telling people that you have been given a subpoena. Another thing that’s unique about the grand jury is that, unlike all other criminal proceedings, it’s not adversarial. By which I mean, there’s not a defense attorney and a prosecutor, and there’s also no judge. And also, because it’s secret, there’s no public. The only person who’s there is the prosecutor, and they get to present the case to the grand jurors, and they get to control the narrative and decide what to include and what not to include, and that is why nearly 100% of cases presented to a federal grand jury are indicted, but somehow federal prosecutors almost never indict police.

Unlike a trial jury, where jurors get questioned about their histories and ideologies by a prosecutor, a defense attorney and a judge, federal grand jurors don’t get screened for bias at all, and there are practically no rules of evidence in a federal grand jury. So if you ever watch a [police] procedural [on tv], you’ll see that in trials, the attorneys make objections, right? And there are these objections that you can make to irrelevant evidence or illegally obtained evidence or hearsay. Those don’t apply in the federal grand jury: they can basically present whatever, even if it’s totally irrelevant, even if it was illegally obtained. There’s all of these things that they can just throw in. And then maybe the biggest thing is that, unlike when you’re being questioned by law enforcement, participation in the grand jury can be compulsory, meaning that you can face consequences if you refuse to participate.

Now, please don’t despair. There are a lot of ways to challenge a grand jury subpoena, and I’m not going to get into it right now, but basically what you need to know is, if you get one of these, reach out immediately, and the NLG will help you to find an attorney in your area who is able to actually represent you. Well, it’s just a pretty unusual area of legal practice for lawyers. And if there are grand jury subpoenas that are happening in your area, I would say there’s a lot of education available to you and your community, which is like not just legal education, but historical education and political education. The short version here is there are potential risks and downsides to basically every available option. With respect to anyone who receives a grand jury subpoena, there’s pretty high risks of different kinds of sanctions, even for people who aren’t a target of the investigation, for people who are just called as witnesses, even, and sometimes especially, if those people don’t even know anything. So in this situation, even this weird situation, you still have constitutional rights that you can assert in. Including your Fifth Amendment right to remain silent, and there are legitimate legal defenses to challenging the validity of a grand jury subpoena, and those deserve to be fully explored before you’re even able to decide whether or not you want to cooperate with the grand jury. Because you don’t even know until you do a certain amount of litigation around the validity of the subpoena, whether you can be required to answer questions, and you have to know that before you can decide whether or not to answer those questions, right? So if you have what is determined by a judge to be a validly issued subpoena, then that means you must answer questions or face certain consequences for refusing to answer those questions, which include being found in contempt of court, which can mean that you get sent to prison for up to 18 months without even being accused of a crime. And if you decide you do want to cooperate with a federal grand jury, then the consequences do not simply include snitching about other people’s actual crimes. They also include disclosing information about people and movements that’s totally lawful but could be used to justify surveillance and targeting and further intrusions or to engender conflict in your community, right? It can and often does mean that the person who’s giving that testimony ends up themselves being subject to federal prosecution, even for things that we would never have imagined would constitute a federal crime.

So if you get a federal grand jury subpoena, please just call the hotline. I would encourage you to tell folks that you’ve been given this subpoena, because this is a situation where you really are going to want a lot of community support no matter what you decide to do. So on that note, no matter who your lawyer is, I want to be really clear, nobody but you can decide what you want to do if you are subpoenaed to give grand jury testimony. That is just not a legal question. It is not a question your lawyer can answer. It is something that you have to decide for yourself, on your own, or to whatever extent you want to, in consultation with your community. And I would really advise people who are in movement communities to think about all of this, to do some grand jury education and to think about what you might do under different sets of circumstances and make agreements with each other about it. You know, depending on what people decide, I would encourage people to do things like set aside money for legal expenses and social support for anyone who might end up on the wrong side of a grand jury, including people who might be exposed to criminal liability as a result of somebody else’s cooperation with a grand jury.

For any community experiencing Grand Jury repression, social solidarity, public education and media work are critical. I would say putting together not just a legal team, but a really robust social support team is crucial. And all over this country, there are legal workers and folks who have both provided and received that kind of support, and they are really generous with their time, energy and expertise. Again, remember that even if you end up in a terrible situation where you have a grand jury subpoena, you do not have to go through this alone. You have your community and all of you have all of the many resources that have emerged to support people in this situation and to support targeted liberation struggles. Over the last century,

TFSR: You were specifying federal grand jury. Are there state and local level grand juries? And is the approach any different, or is it just call the NLG? They’ll direct you towards the appropriate like legal defense and such.