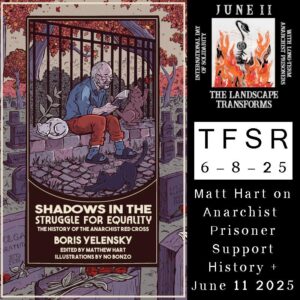

This week on the Final Straw Radio, we’re sharing an interview with Matt Hart of the Los Angeles Anarchist Black Cross chapter of the ABC Federation. We talk about the book Matt just released via PM Press, an expanded edition of Boris Yelensky’s history of anarchist prisoner support “Shadows In The Struggle For Equality”, illustrated by NO Bonzo. Matt talks about the work of the LA-ABCF, ABC’s pre-history with the Narodnik movement in mid-19th century Russia, prisoner defense under the nihilist movement, some moments in resistance and mutual aid through the following hundred and fifty years or so, some colorful moments and comrades up into the 21st century. We hope you enjoy! [ 00:01:16 – 01:19:36 ]

Then, we’ll share a reading of the 2025 June 11th statement since this week is the day of Solidarity with Long Term Anarchist Prisoners. More info on that initiative at June11.noblogs.org and the original text can be found there [ 01:19:41 – 01:30.51 ]

. … . ..

Featured Tracks:

- Filmmuzik by E.M.A.K from Deutsche Elektronische Musik

- Vienna Arcweld – Fucked Gamelon – Rigid Tracking by Set Fire To Flames from Signs Reign Rebuilder

. … . ..

Matt Hart Transcription

Matt Hart: My name is Matt Hart (pronouns – he/him). I’m a member of the Los Angeles chapter of the Anarchist Black Cross Federation.

TFSR: Thanks a lot for joining. Congratulations on the publication of Shadows in the Struggle for Equality in book form.

Matt Hart: Thank you very much. Very happy to have it.

TFSR: Me too. There was a zine edition that you put together, called “The struggle for equality. The History of Anarchist Red Cross”, and a shortened version of it: “Yelensky’s Fable: A History of the Anarchist Black Cross.” Both of which I’d seen over the years and didn’t really put together with this project, or you, even though your name’s on it. This is a really important piece of anarchist and anti-repression history. I wonder if you could tell us a bit about the original text. How you came to be aware of the work of Boris Yelensky, and a bit about his life.

Matt Hart: Yes, so first, how I came across the text. I was completely unaware of Yelensky before I even received the book. However, at that time, I was a member of the Los Angeles chapter. We formed it back in ’98 and I tend to want to know as much information about the projects that I’m involved in as possible. I usually try to do a deep dive, but one of the things that we found was that a lot of the history just wasn’t there, it simply wasn’t. As much as we kept on looking and looking, there might have been tidbits of information here or there, but there wasn’t a lot of historical information out there about its early years, maybe just a couple of references to it starting around the 1905 revolution, but nothing that concrete. There was Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin’s call for a network, but before that, there just didn’t seem to be a lot of information in terms of especially early 20th-century history. Interestingly, my partner came across it, she actually bought it for me for Christmas. I had never seen it before, had never even heard of it before.

The individuals that I worked with in terms of the larger Anarchist Black Cross Federation were unfamiliar with it as well. It was a treat. It was something that fell into my lap or was given to me as a Christmas present, and it just started after that. Not only did it give me direction on where to look, but it created obsession in terms of trying to uncover as much history as possible regarding the Anarchist Black Cross. That’s how I came across it. The book itself was published by the organization back in 1958, and the idea was that it was going to be telling the history of the anarchist Red Cross from Yelensky’s perspective. There is a bit of a controversy with it, if you look at some of the corresponding letters back and forth between Yelensky and some of the people who were involved in the Chicago branch. There were certain things, such as conflicts between the organization and other organizations that they didn’t want to have in there. Ultimately, I think it does provide an interesting insight into some of the biggest problems that we’ve had within the larger revolutionary movements, which is how conflicts affect some of the work that we do, especially when it comes to prisoner support.

TFSR: Cool. I want to get a little bit into Yelensky’s life, but I want to clarify also the way I framed the question. I made it sound as though it was a forgotten history, or that this stuff is unknown. This stuff is probably known to a lot of people. As far as the earlier history, it’s known to people in former Soviet states in Eastern Europe, in Jewish radical enclaves in various parts of the world that would have escaped from the hands of the Soviets, or would have been running from czarist repression beforehand, or what have you. As much as we may have a common linguistic and maybe cultural anarchist ancestry to the people that were involved in this, maybe this history fell out of our hands. I would imagine, it wasn’t totally lost.

Matt Hart: Yeah. That’s probably more accurate. We definitely had a lot of people who participated in the Jewish anarchist movement and Jewish anarchist history. I mentioned this in the forward: if you didn’t necessarily know where to look, and if you’re doing research in English, for example, it’s going to become a lot more difficult to find. There is definitely a lot of access to the history. If you start looking in Russian or Yiddish, for example, that history does exist. At that time, there weren’t really a lot of historians, other than Paul Avrich, that were looking into that area. I would make an argument, that those of us who were part of my generation of the Anarchist Black Cross, weren’t aware of the fact that that’s where we needed to look, that these are the stones that you need to look under. That was part of the problem for some of us. We just didn’t know that history was there, it was spoken about. I also did mention in the foreword that the London Anarchist Black Cross was well aware of Yelensky. They had him even in their publications back in the late 1960s, they did speak about Yelensky and about the book, but when we’re talking about a lot of the Anarchist Black Cross members during the late 80s, early 90s, I think that history dissipated and was never passed on to this current generation. If that makes sense to you.

TFSR: For sure. When I was reading, especially into the introduction where it was referencing names and groups that I was familiar with. It makes sense that Stuart Christie and Albert Meltzer would have heard of ABC and they didn’t just create it out of whole cloth, right there. These continuities and connections existed, but maybe they were like tendrils or roots or rhizomes under the surface. I could recognize the little sprouts that I’ve seen historically, but maybe wouldn’t make the connection. Like, these are some of the ways that they were connected, these are the ways they were transmitting their history, knowledge, resources, or whatever. I think it’s pretty cool. It’s great that you were able to pull this into such an accessible volume. I’m excited to talk to you about it.

Matt Hart: Absolutely. Thank you. When you start looking at the history and uncovering it, you are seeing just little leaves of grass popping up. For example, we have people like Emma Goldman and Kropotkin, Berkman, and all these other people that are fairly known folks, but in terms of their roles in doing political prisoner support work or working specifically within the Anarchist Black Cross, Anarchist Red Cross, that information isn’t necessarily so much out there. Take Rudolf Rocker for example. We know him more because of his writings, but in terms of his involvement doing political prisoner work, that’s not something that we’re so well informed about.

TFSR: Could you tell us a little bit about Boris Yelensky’s life, its trajectory, and some of the projects that he was involved in?

Matt Hart: Boris Yelensky was born in Russia in February 1889. His father was a cap-maker, and he lived off of this port city, off of the Black Sea. Growing up as a young person, that port was oftentimes used to transfer inmates who were going to Siberia or coming back and forth from prisons. It was a very common for him to see people in shackles, people who were in poor health conditions, who were beaten, bruised, and battered by the prison industrial complex and by the guards themselves. He saw this, and this had a strong effect on him. If I remember correctly, at the age of 12 or so, he came across a bunch of revolutionary material, which really piqued his interest. He then got more involved, became educated, joined the Union of Socialist Revolutionaries, and then participated in the 1905 revolution. Because of his involvement in that revolution, the police began to go after him. They began to do some raids on his house, so he had to escape. He came to the United States, and he first landed in Philadelphia. There he got more involved in the anarchist movement, became part of the radical library, and was soon involved in the anarchist Red Cross Philadelphia chapter. He then met his wife, Bessie, and they then moved to Chicago, where they helped start the Chicago Anarchist Red Cross. From then on, he just became more involved. He got involved in the Union of Russian Workers, and he was involved in the political movements in Chicago. Then, when the Russian Revolution happened, he went to Russia, was arrested several times for his anarchist activity over there, and then he came back and continued the political prisoner support for those folks in Russia. He then spent his life until 1974 continuing to work on providing support for political prisoners.

TFSR: And then he did what most of us dream of: retiring.

Matt Hart: Yeah. Retiring and moving to Florida, apparently. What was interesting about both him and his wife, was that both of them were dedicated revolutionaries. They were both very much involved in political prisoner support in all different facets. Also, when World War II happened, they were involved in trying to get as many anarchists, and Jewish anarchists in particular out of Europe as possible, for the obvious concerns of them being swept up by the Nazi regime. They were successful in a lot, but unfortunately, they weren’t as successful as they’d like, and a lot of people perished. That was a big lift that the ABC, or Anarchist Red Cross was involved in at the time.

TFSR: I was absolutely floored with the introduction of the book that you wrote. Not only about the pre-history of the ARC, or the Political Red Cross, or whatever it was named at various points, or the bits about the early US chapters, but the second and third waves as you describe them. It filled in a lot of gaps for me. When I was talking about the tendrils or sprouts or whatever, I was making these connections, tying in movements for liberation and the defensive organizing that I was at best, peripherally aware of at times. Can you talk about some of the pre-history and history of this tendency that you follow in the book?

Matt Hart: Oftentimes, when I talk about the history of the Anarchist Black Cross, I’ll occasionally use the term Anarchist Red Cross. I mean the same organization. At one point it was was referred to as the Anarchist Red Cross, and then it transitioned later on. I want to make sure that’s clear. I oftentimes break it up into three waves, but it can be argued that there were four waves. The first one was prior to the development of the Anarchist Red Cross. At that point, we had people that were involved in an organization called the Political Red Cross. There’s not an exact moment where we can pinpoint the formation of the Political Red Cross, because there were various different organizations that were around in the mid-19th century that were doing this type of work. We can certainly see the people involved in the Political Red Cross during the movements of the Narodniks, and Land and Liberty folks. It’s also called Illegal Red Cross or Revolutionary Red Cross. These terms were thrown around at the time, but there were some people doing prisoner support work and involved in liberating people out of prisons who belong to different revolutionary organizations.

Around that time, around Land and Liberty, around Narodniks, this is where we start seeing the development of the Political Red Cross. When the People’s Will took form, we started seeing the Political Red Cross not just as an internal organization within the land of Russia, but we now see its development outside of Russia. We start seeing support in places like France and London. We actually see a more formal structure of support being provided to Russian prisoners internationally. So the People’s Will developed the Red Cross of the People’s Will. It had active branches in London, which Chernyshevsky and Kropotkin were involved in. We also see it in Boston, where we see Benjamin Tucker, who was very much involved, being a spokesperson for the organization here in the US. He was involved in fundraising in Boston and reaching out to various revolutionary communities to provide support for those Russian prisoners.

I think one of the things that’s interesting throughout the history of the organization, is seeing who was involved in what period. During this period of time, the individuals who were mostly involved in doing this type of work were not completely, but almost consistently women who were involved in this movement. So much so that it became a criticism as to whether or not this was something that was being viewed as not serious work, or “women’s work.” That actually became a point of tension for a lot of these women revolutionaries who were making the argument that they wanted to be more involved in doing more revolutionary activities, rather than providing prison support. Those components existed at that time, and that’s when we get to what I refer to as the first wave of the Anarchist Red Cross. This was during a period of time when we saw anarchists involved. Like I said, we’ve got Kropotkin and Tucker involved in doing a lot of the heavy lifting in terms of fundraising. One of the things that we see is that within prisons, those funds weren’t always getting to anarchists. If Marxists had the majority inside specific prisons in Russia, what we saw oftentimes was that the funds weren’t being given to anarchists, so anarchists broke away around the 1905 revolution. Again, there’s a dispute about when it actually formed, but it was shortly after the 1905 revolution that the Anarchist Red Cross formed itself. Yalinsky does talk a little bit about how some of the individuals were involved in forming it, we can talk about potential periods, but an actual date, a month or even year, to some degree, is difficult to nail down. One of the components of this generation is that we see the individuals that were mostly involved in the work, both within Russia as well as internationally, are predominantly from the Russian Jewish community. They were individuals that oftentimes were prisoners themselves, people who had escaped, or had been exiled, those who had been in prison and one point and then released, then fled Czarist Russia. When they would go to the UK or the US, they would oftentimes organize Anarchist Red Cross chapters to provide support for the Russian prisoners.

Again, we see certain trends within this period because the support work was aiming for specifically Russian prisoners or people that are part of the Russian Empire, like Ukraine, Poland, etc. That was one of the key characteristics of this period of time. Then we get to the second wave of the Anarchist Red Cross. The second wave began to form around Stuart Christie. There was an anarchist in London named Albert Meltzer who was providing support for Stuart Christie. Stuart Christie was a Scottish anarchist who had been part of the Libertarian Youth movement and a part of a plot to assassinate Franco. The plot was foiled. Apparently, he didn’t realize that he would stick out like a sore thumb by wearing a kilt. It’s a little bit more than that: the English and the Spanish governments were working hand in hand, providing information about the libertarian and anarchist movement at that time. England had provided Spain with information about Stuart Christie coming over and he stuck out like a sore thumb because he was wearing a kilt when he was caught and arrested. So there’s a little humor, at least from his perspective, about being caught that way. Once he was released, he and Albert Meltzer came together to form, or at least reignite, the Anarchist Black Cross. Then it spread through Europe and the US and continued to grow.

Then we basically moved into what I would argue now is the third wave, which is our current wave. It has been greatly influenced by Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin’s call for the Anarchist Black Cross Network, which was published in 1979. I can go more into the various sorts of characteristics, but that’s a rush job of the different waves of the movement.

TFSR: Yeah, folks should read it themselves to learn more. I thought that this history, which includes the Breaking the Chains conference, the ABC network, the formation of the Federation, and all the different chapters and the personality conflicts you touch on, were all really fascinating. It put together some stuff. As an anarchist in my 40s who got into prisoner support rather later, I recall seeing some of that stuff circulating. When we got in touch, I was interested in the history of ABC, and I remember reading a pamphlet maybe in 2003, that I found at Liberty Hall in Portland about the ABC chapter in Jacksonville being repressed. The federal government was targeting it because they had a tactical defense caucus, and they were participating in shooting matches and stuff that law enforcement was also participating in, if I recall. I remember seeing support materials for this, but then I had so much trouble finding any information. People didn’t want to talk about it, maybe for good reasons, afterward. There’s so much history in there. I hope that this book will invite more research and more drawing of those lines.

Matt Hart: It’s interesting because I have been a part of this organization since ’98, so a lot of that stuff was stuff that I was not only a witness to, but was directly involved in and sometimes even unknowingly. For example, touching on the Break the Chains conference, there was a gentleman named Brenton who was part of the chapter that was up in Eugene and helped organize it. I’m touching on this for a very specific reason, because of the general theme of the book, which talks about how divisions undermine our movement in our communities. At that time, the Anarchist Black Cross Federation and the Network were at odds. I definitely have my reasons and my biases about that, and we can get into them or not, but either way, there were divisions. One of the things that we started doing in, at least the LA chapter, is we started sending out messages of solidarity to all organizations, regardless of whether or not they were part of the Federation, the Network, or not associated with any organization. And so Eugene responded, and then Austin ABC responded. As part of that, when Break the Chains, which was an Anarchist Black Cross Network conference happened, we were brought up there to do a workshop on the history of the Anarchist Black Cross.

It was interesting because obviously there were a lot of tensions that were still very much there at that point. But the whole point of our workshop or presentation was that if you look at our history, at Yelensky’s book, if you just take the time to look into what has happened to our movement when we are fighting against each other, the people that suffer the most are the prisoners. Just around that time, there was an individual named Thomas Warner who wasn’t an anarchist prisoner, but he was a Black Panther political prisoner who had been in jail for decades. He was not very well known. He was on a lot of lists, including the ABCF’s list, but nobody really communicated with him. When we finally reached out to him, we got a letter back from the prison that said “dead” written across the envelope. So we tried to do more work, we tried to reach out to anybody who might have know him. Finally, we found a website that talked about how he was depressed and didn’t have a lot of support, he had somebody snitch on him, which basically prevented him from receiving early release or being paroled. He became so depressed that he slit his throat and died.

This was something that had just happened at that point. So the question that we put out there was: “How many people are we willing to see die because our infighting seems to be more important than the work that we’re doing?” We need to make sure that we need to be active in trying to squash it. That was actually the very first time that ABCN and ABCF people sat down together and had a conversation on how to squash this conflict that we were all responsible for. Most of the people that were there at the conference weren’t even the people that were leading the fights. Some of those folks had said that they were going to boycott the event because we were there, but we were able to all sit-down, and we were all able to move forward and squash that. Then we continued to build cohesion together as two different organizations working together, and we tried to basically squash those issues.

We see what happens when our communities focus more on our divisions than the work that we need to do. Going on that history, during that period of time, especially around 2003-2005, we saw a series of repressive actions against both the ABCN and the ABCF. We had our Jacksonville chapter raided multiple times, picked up by the FBI, and we had a Grand Jury. We didn’t know at the time, but there was a Grand Jury investigation against both Jacksonville and LA, because of our involvement in the tactical defense caucus, just learning how to use self-defense. According to the FBI, they felt that we were trying to create a revolutionary underground movement, which wasn’t true. We were just practicing self-defense, and at that point, we didn’t know that there was a Grand Jury hearing. That never amounted to anything, but it still showed us that they were very much focusing on both us and the ABCN in terms of trying to undermine or prevent the work that we were doing.

TFSR: Some of the justification was that you were attempting to recreate a sort of Black Liberation Army-style organization, which sounded like it was based on the prisoners that you were supporting.

Matt Hart: There were a lot of the prisoners that we did work with who came from the movements of the 60s and 70s. So you had a bunch of white new leftists, you had people that were part of the Puerto Rican independence movement, you had people that were part of the Black Liberation Army or Black Panther Party. The vast majority of the folks that we were providing support to happened to be people of color, because they were the ones that oftentimes got the heaviest prison sentences and felt the full weight of the state in terms of cracking down on their organizations, like the Black Panther Party. It even got to the point where they suspected that we were trying to hide Arthur Lee Washington, who was on the 10 Most Wanted List. They suspected that our chapters in Jacksonville and New Jersey were harboring him in some way. So they began investigating the lives of ABC members in those chapters. They weren’t harboring anybody, but for some weird reason, they, the FBI, had it in their heads that we were doing that. Then when the leader of the Los Macheteros was assassinated, they picked up one of our members, because somehow they thought we had some weird connection with them. After all, we were doing work with the Puerto Rican independence movement, or at least providing support for their political prisoners. Somehow they thought that because we were connected with the prisoners, we were connected with the underground aspect of those movements or organizations, which wasn’t true. That created a tremendous amount of attention around our organizations. Then when we started learning how to defend ourselves, they took the position that we were trying to create something similar to the armed guerilla groups of the 60s, the Black Liberation Army in particular. There was no merit to any of that in any way, shape, or form, but that didn’t stop them from making those accusations.

TFSR: On that note, do you mind if I keep digging around in this period of history? One thing that didn’t come up is that sometimes there will be peripheral organizations that are talked about, that the ARC decided to use. Yelensky would say: “We had to go and have a meeting somewhere else, so we used the IWW Hall down the road,” or whatever. There are relationships with other radical organizations. I’d be curious to hear about the impacts of Love and Rage on the formation of ABC if that’s worth commenting on. Also, 1998 is when the National Jericho movement, roughly was formed. Considering that you were supporting some similar prisoners around the same time, and there’s a big push for Mumia (Abu-Jamal – Ed.) and for Leonard Peltier at this point too, I wonder if there was influence from National Jericho being formed simultaneously.

Matt Hart: First regarding Love and Rage. So our New Jersey chapter when it first formed into the Anarchist Black Cross, they were also part of a New Jersey anarchist organization as well: Patterson Anarchist Collective, if I remember correctly. They were actually part of Love and Rage, so it definitely had a lot of influence. If you do recall a lot of their later publications, they were doing a lot of work in terms of promoting the Anarchist Black Cross and our conferences, letting the anarchist community know that this formation was taking place. I do think that there were a lot of folks who were involved in the Anarchist Black Cross who were also involved in the Love and Rage Federation, and then, as the Love and Rage Federation dissipated, or moved on, they continued their work within the Anarchist Black Cross. Also interesting enough, some of the people who were involved and helping to form the LA chapter were also involved in Love and Rage as well, but the chapter over here had dissipated by the time we had started.

Regarding Jericho, we worked side by side with them constantly. As a matter of fact, in LA, we had the Jericho Amnesty Coalition, which consisted of various different organizations that LA ABC was a part of. In Philadelphia, our chapter worked pretty consistently with Jericho and a lot of our folks were part of the first Jericho parade that took place, I believe it was in DC, if I remember correctly. Actually, when that parade took place, that was the first seedling of the LA chapter, because one of our members, Frank, as soon as he came back, started the chapter because of his experience out there talking to both the Federation as well as Jericho people.

TFSR: Regarding the point you made about squashing beef and finding support for the prisoners as a common cause among different organizations that may have ideological or personality differences, the other side of that is that united fronts often support the more powerful projects. One of the lessons also from the book, is that making common cause for radical prisoner support can sometimes mean that minoritarian prisoner groups that you may have more affinity with don’t get the support because the Social Democrats, or whatever, redirect the funds to their prisoners. Perhaps the distinction lies in the fact that these are not anarchists, which is a significant dividing line.

Matt Hart: I definitely can see that argument. I can’t speak for ABC and I would never do that, but it’s an argument that could have been made at that time, because of the fact that ABCF had already been established. Some criticisms were grounded, had merit, and definitely had some meat on those bones in my humble viewpoint. And that’s coming from somebody who was a part of our organization. I also think that because of our history, because of the fact that we were already dominant within the political prisoner community, it was a bit of punching up. To attack the Federation is punching up a little bit, right? That’s not to dismiss that ABCN. They did absolutely amazing work, and their presence really did do a lot to benefit our movement. As much as there was a rift between our organizations, they were something that was necessary to develop at that time. Even in terms of challenging ourselves as an organization and some of the ideological issues that we had within our organization, not only did that split need to happen, but there needed to be at least some level of disagreement and debate within the movement.

The only issue is that the debate itself became paramount, it became the focal aspect of the work that we were doing. Rather than only seeing that we disagree and debate on these issues, we could have asked what are other areas in which we can find common ground and continue to work on. It came to the point where just sharing space was an issue. That even included organizations more largely. There were ABC organizations globally, but certain organizations were kept out because of disputes. It’s one of those things where it became too divisive. All the work and all what we were trying to do was lost in the mix. But I agree with you that there’s an argument to be had about how sometimes these organizations can shift resources and can have an influence on the politics, terminology, perspectives, or anything else that influences a movement. Larger organizations can sometimes overshadow other organizations or communities.

TFSR: To switch the questions around, since we’re already talking about the Federation a bit, could you talk about the history and work of the Los Angeles chapter of the ABC Federation and the wider Federation? What do the Federation and the chapters do? How they’ve developed? In particular, with the focus on Los Angeles.

Matt Hart: LA started back in January of 1998. A lot of us had been involved in various different organizations, locally. Some of us were involved in Food Not Bombs. There was an organization here in Whittier called the United Anarchist Front that many of us were involved in. I wasn’t, but a few of the people that started our organization were. There was also the Alternative Gathering Campaign, that was around here, that would do a lot of making up pamphlets and shirts and that kind of stuff. We were all involved in different projects locally, and a lot of us had begun to kick around the idea of forming an ABC. We wanted to do something that was more directly connected to the concepts of mutual aid and something around the prison industrial complex, because a lot of us had our lives impacted by the prison system in a personal way. So to us, engaging in Prisoner support just seemed natural.

One of our members, Frank, had gone to DC. He had already been corresponding with New Jersey, and so he participated in the parade out in DC and spoke with the Jersey people. When he came back, we all sat down and decided to form the LA chapter. I think we are, if not the longest-running, then we’re certainly one of the longest-running Anarchist Black Cross organizations, and the longest-running anarchist organization in Los Angeles. If not, the longest-running, then the second longest-running Anarchist Black Cross organization in North America. We’ve been going on for a number of years, and hopefully we’ll continue. We’ll see.

Most of the work that we do is local. Besides the obvious basic support of writing letters, correspondence, and visitation of prisoners, one of the things that we did help start was Running Down the Walls, which is a 5K run to raise money for political prisoners. It provides a lot of the funding for the Warchest, which I’ll talk about in a minute. That’s been going on since ’99 and ever since that run, it has spread to prisons, to other places in North America. We’ve had a few runs outside of North America, and every year it just seems to grow bigger and bigger and bigger. That’s a project that we’re pretty proud of. That is something that has continued. One of the questions that have come up, has been about creative forms of fundraising. I think that’s sort of a more modern version of creative forms of fundraising if you will.

TFSR: How does the fundraising work for that? If a bunch of people want to get together and do the run, do they go and solicit pledges, saying: “I promise to run this if you give me this amount of money?” What does that look like?

Matt Hart: Yes, yes, yes and yes. It’s various ways. Some people can get sponsorship. There’s organizational sponsorship as well. I think each chapter does things a little bit differently. When we started, one of the ideas was to get organizational sponsorship, where on the material, on the shirt, or any sort of thing like that, if an organization donates, you can get your logo on, just like any other type of run. Then, there’s also a sponsorship: “If I do this run, would you donate?” So people will sometimes come with sponsors. Then there’s just also giving a flat donation, whatever people feel. We try to have a base donation, but at the end of the day, we’ll accept anybody who wants to participate, regardless of whether or not funding is there, regardless of whether or not they have the funds.

Every chapter is different. There are certain organizations and certain runs that will split the funding, for example Casey Goonan. If organizations want to raise funds for them, they can. They can have a specific fund for them to be able to send into their support network. There’s fundraising for Atlanta in terms of the defense stuff that’s going on over there. So each organization can decide how the funding will split. We do ask that a portion of the funding go to the Warchest because that’s part of our main project. If folks want to just decide to get together and do a run in a city, and it’s a small group of folks and they want to throw into a hat and then send the funds to the Warchest or whatever program they want to support, they can. As far as we’re concerned, the more that are involved in this, especially if it’s there to bring solidarity to our comrades in prison, so be it, we’ll absolutely support that. That’s the idea behind the funding. There are just different ways. Be as creative as you want to be in terms of trying to find ways to raise funds.

TFSR: You’ve mentioned the Warchest, that’s a product of the Federation. Can you talk a little bit about what that does, who you support, and the nature of it? How does it differ from fundraising once a year for June 11, or the Week of Solidarity, or whatever?

Matt Hart: To answer your question, the ABCF Warchest started around 1994. It actually started as a concept even before the Federation started. The idea is that there are certain folks who have been in prison for so long that their community no longer exists to provide consistent funds to them. That was why it started. Over the years, what we’ve done is we’ve provided monthly stipends to political prisoners who receive little or no financial aid at all. As of right now, I believe we’ve got 14 individuals on our Warchest that range from Oso Blanco, Hanif Bay, Malik Smith, Ronald Reed, Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin, to Marius Mason. The list goes on in terms of folks that we provide consistent support work for. And again, we raise the funds. It’s not only the monthly stipends. If there’s an emergency fund that needs to be sent out, then we’ll send out those funds as well. For example, Alex Stokes , we provided recently some funds to his legal defense as well. So yeah, we try to raise as much money as possible so we can add more prisoners and provide more support to our larger community.

TFSR: Could you talk a little bit about the writing process for the book? You were gifted the pamphlet that was the basis for it, a short booklet. How’d you gather further material, besides the introduction? What extra material did you bring to Yelensky’s original?

Matt Hart: Well, I’ve been working on collecting information for probably about 20 years now. I have a significant archive of ABC material at my home that has documents as far back as the 1920s. Over the years, I’ve just been collecting and collecting and collecting. When I used to go to the Anarchist Bookfair up in San Francisco, Barry Pateman, every single time he saw me, he would all of a sudden bring up a large stack of old Black Flags that he had collected and literally put aside for me. So every year I would just come back with more stacks of Black Flags and other stuff related to ABC. That really helped in terms of digging through research, or at least provided research material. At that time when I came across that book, it was the early stages of the internet, so finding material about the Anarchist Black Cross, especially historical documents, other than current websites, just wasn’t there. I think now it’s a lot easier to do research, especially even when it comes to translation. Right now you can find the old Fraye Arbeter Shtime, (Free Worker’s Voice), with the ability to translate it using various apps. I’m now able to actually do research through those magazines as well as other Russian magazines or newspapers. That has actually helped with the research considerably. So Golos Truda, Fraye Arbeter Shtime, those have been pretty significant resources through this process. And then old FBI files. If you’re into doing stuff like research, ancestry.com, also has a sister site called fold3, that you can actually pull old FBI files from. So I’ve been able to find stuff, especially regarding informants. I’ve been able to find information regarding informants through that, and none of the stuff is blanked out. You’re actually able to get the identities of the individuals that were informants at the time.

TFSR: That is crazy, I did not know about that, that’s weird. That makes sense. I mean if it’s not redacted, then it did not get released through the regular FOIA requests?

Matt Hart: All I know is that I came across this website, I checked it out, and I started doing some research regarding early anarchism, and started coming up on a lot of stuff. I’ve been using it as a primary source material, especially when it comes to old FBI stuff for the organization. None of it is redacted at all. I don’t know when it was released, how it was released, or anything like that. I just know that this information is available and it’s useful material, especially since you can find stuff on the Magonista movement, and you can find stuff on the IWW. That has a tremendous amount of resources regarding the IWW, including old subscription lists that you can come across. If you’re interested in doing anarchist history digging in your community, it’s actually pretty useful. If you ever wondered why one of your aunties was always calling your other uncle a snitch, you can find out if it’s true.

TFSR: I’m a 25% snitch from Chicago, according to this. Yeah, that’s crazy. So you included a few extra documents to contextualize the original publication in the appendix, right?

Matt Hart: Yeah. I thought, well, one of the things that was really interesting, because it’s an ongoing debate within the Anarchist Black Cross movement, is the support of non-anarchist political prisoners. One of the reasons why I provided this as a resource is to highlight the fact that this has been a debate that’s been going on for well over a century at this point. And so it’s a debate between Lilly Sarnoff, who was part of the Anarchist Red Cross in New York, and Alexander Berkman, who I believe at the time, was in Berlin, if I remember correctly. Lilly was pretty critical of Berkman, not only because he was using his name to gather more support and pulling support away from organizations like the Anarchist Red Cross, but that some of those resources were not only going to anarchists, but they were going to leftist Socialist Revolutionaries or other folks. Berkman’s criticism at that point was: “Look at some of these individuals that we’re providing support for. They’re legitimate revolutionaries who are suffering the same repression as the anarchist community, and some of these folks are more revolutionary than some of the cranks.”

For me, that was a big chuckle, because it’s that ongoing debate that has continued about who’s more revolutionary and what a proper revolutionary is, or what a proper anarchist is, and you’re not a real anarchist, and I’m more of an anarchist than you, and I’m red, you’re green. Those sorts of things have certainly affected and infected our community for the last several decades. But we can see that even back then, he’s again, yelling that the Stirnerites aren’t really anarchists and aren’t really revolutionaries, and they’re part of the cranks. So I kind of chuckled to myself when I saw that. It was definitely one of those things that I needed to contribute to the book. Then one of the big things that I don’t understand why Yelensky has left out of the book was the Lexington Avenue bombing and the involvement of the Latvian Anarchist Red Cross, and why that was completely taken out and wasn’t even mentioned in the book. I don’t have an answer for it, I simply don’t know, but I felt that it was important to add that back into the history and make sure that that was mentioned.

TFSR: Could you describe that situation for folks?

Matt Hart: My dates may be a little murky, so please bear with me. I believe it was 1914, there was a massacre that had taken place in Ludlow, Colorado during a mine worker strike where troops were brought in, and a bunch of people were killed. But one of the things that was more tragic was that, when the troops came in they poured kerosene on a bunch of tents and lit them on fire. Twenty-one people, primarily women and children were killed. This created widespread anger within the broader labor movement. Certainly, the anarchist movement was outraged by what had transpired.

There were all these different plots to organize against, to seek revenge against Rockefeller (John D, Jr – Ed.), who they felt was responsible for the massacre. One of the plots that was devised was a plot to plant a bomb at Rockefeller’s home in Tarrytown New York. So there was a reason why the plot didn’t take place, and they cancelled it. They took the bomb back to the tenement on Lexington Avenue where Louise Berger lived, and unfortunately, the bomb went off killing a bunch of people. Louise Berger was one of the individuals who survived, but her half-brother and another member of the Latvian Anarchist Red Cross didn’t survive. Then some other folks. Marie Chavez was another individual who didn’t survive as well. Some people did survive the bombing, but several people were killed. That’s the history of that incident.

There’s a pretty comical part that goes with it, where Berkman had the urn and was going to the big rally that was supposed to take place. Police and the fire department tried to shut it down, but it got too big. Instead, what they thought was that if they grabbed Berkman and Berkman had got the ashes, then the event would be cancelled. So they tried to arrest Berkman. Berkman got away. They got in the car chase. Berkman was in a big red car, and when he drove up to the demonstration, police there misidentified his car as the chief of the fire department, so they let him in, and he drove up to the very front before they even realized that it was actually Berkman with the ashes. So there’s this comical story that is attached to that story. So I added that as well as part of the book.

TFSR: That’s crazy. That’s great. Thank you so much for breaking that down. I love the artwork provided by no Bonzo throughout. Can you talk about putting faces to the names mentioned in the book, particularly for these women who so often get erased out of histories or are known only as the partner or the lover of this or that famous male activist or writer?

Matt Hart: What’s important for me to put out there, right out of the get-go, is that that wasn’t my idea in any way, shape, or form. That was no Bonzo. I’m definitely going to give them all the credit in the world for really bringing that aspect into the project. Not only that. It was really no Bonzo that was extremely critical in making this even happen. We had spoken about it before. I had spoken with PM before about doing it, and really, what happened is PM and no Bonzo got together to decide to engage in a full court press. They basically said: “No, Matt, we’re doing this, and you need to get going. This project needs to happen”. This is an aspect that they brought into this project completely. And I think it to the point that you are mentioning how important it is that not only are we seeing these faces, but that the faces that are oftentimes overshadowed in our type of work or movements in general, be sort of brought out and that light be shown on them.

When you look at the history of the Anarchist Black Cross, especially in Russia, and you’re looking at, just to name a few: Lea Gutman, Helena Ganshina, Tatiana Polosova, Mollie Steimer, Olga Taratuta, these are all individuals that were arrested because of their involvement in The Anarchist Black Cross in Russia. All of them had been in prison, and some of them, like Olga Taratuta, literally lost their lives during the Stalinist purge because of their involvement in not only the revolutionary movement but also their hand in the Anarchist Black Cross. So I think that no Bonzo is certainly helping to bring these names out into the picture and then also in the process, influencing what information is being put in. When I was talking to no Bonzo, when we were collaborating, no Bonzo would sit there and say: “I’m gonna do this artwork of Olga”. And I’m like: “Okay, what?” Now I need to start highlighting more of Olga’s work, so it makes greater sense as to why we’re seeing some of this artwork. This collaboration between the both of us really brought that aspect out. I can’t, as much as I’d like to, take credit for it. I can’t. It’s no Bonzo’s work.

Even, as we’re talking about this, and we’re talking about Boris Yelensky, I think we’d be remiss if we didn’t highlight the fact that his partner, Bessie, was involved in the movement from the get-go. And again, we’re talking about Boris, yet she was consistent in providing support, being involved, and participating in the revolutionary movements. We know a lot more about him than we do her. And then obviously, Brenda Christie, Stuart Christie’s partner, was arrested and accused of being part of the First of May group that was engaged in guerrilla actions throughout Europe. She was involved in the Anarchist Black Cross, as much as he was. She was arrested in West Germany and accused of making a phone call to plant a bomb on an airline. You’ve got these people that are oftentimes overshadowed because of their male compatriots. That’s something that we need to definitely highlight a lot more and bring to the attention and bring forward in terms of the work that we do.

TFSR: Thank you. So I have to say that the Peasants Ball, which the Chicago Anarchist Red Cross was running in the 1910s, was such a strange and wonderful fundraising method, along with the live tableaus that the New York City ARC and other groups were running. In researching this, were there any novel propaganda or fundraising ventures? You could talk about those real briefly too, but also if other things came out that you would think would be a really interesting thing to try and pull off. A live tableau was so of the time. I can’t really imagine having the same ramifications now as it would have at the time before films were really super available to people.

Matt Hart: So real quick. They had two different balls. They had the Peasant Ball and the Prisoners Ball. Some of the cities organized both, whereas other cities would organize one or the other. It seemed to be the main form of fundraising for them, and they definitely got creative in terms of creating an atmosphere. So they spent a lot of attention and making sure that these were wonderful, amazing events, people dressing up. For example, The Prisoner Balls were masquerade balls, and people would be judged by their costumes. Chicago at their Peasant Ball talked about these things where women would raise funds by trying to force men to marry them, so the men would pay a charge to marry them, and then they would demand a divorce. The women would demand a divorce, so the men would have to pay additional money, and if they didn’t, then they would get thrown in jail, so they had to pay money to get out. So it was these different creative ways of fundraising, but then also, in the same way of course, they had to make their statements about the concepts of marriage and who was the one responsible for engaging both the marriage and the divorce. I think there probably could be some things said about that.

Some of the other ways in which they did fundraising, they had picnics. I think New York also had boat rides on the Hudson. That was something that would happen around springtime every year, especially during the 1910s. They would actually have the boat rides as well as fundraising. Picnics, that was also a big thing that took place in not only Chicago but also New York. One of the things that’s interesting about the balls is, much like with the runs today is it didn’t just happen in Chicago or New York. It happened in Milwaukee, and it happened in Philadelphia. We continued to have Prisoner Balls in LA up until, if I remember correctly, 1927. I think it might even have been later than that, where we continue to have Prisoner Balls out here, and all the funds would go to support political prisoners. So even though we didn’t have an Anarchist Black Cross chapter or Anarchist Red Cross chapter here, there were still fundraisers through the balls for that specific purpose. So in terms of creative organizing, I think probably the balls not only were a common form of fundraising that took place at that time, they have been something that we’ve even thought of as something that we can do here now. And what would that look like now? Would it be us getting all gussied up and dressed up in a suit and tie, or would it be more of like you got the DJ spinning, playing music, a fundraiser that way? So it’s been something that we’ve kicked around for a while in terms of how to actually implement something like that.

TFSR: Costume contest. People love dressing up. Can you talk a bit about other forms of resistance, work engaged by Anarchist Black Cross or Anarchist Red Cross groups in history that you and Yelensky document in this book? What matches with today’s work and what differs, whether in the scope of support offered, defensive work provided, or international correspondence and support? The way that Yelensky frames the book, in a lot of cases in the work in the US, is that a lot of this was happening in exile communities where people had, as he said, participated in these movements themselves, shared a language, maybe shared faith, maybe lived in these cultural enclaves abroad, and they were supporting people from their villages, people of a common political perspective. They all read the same newspapers. There are a lot of differences in the way that ABC seems to function in the US versus how it did in these early days. I wonder, going through those three or four waves, depending on how you use it, if you could talk about how the work has looked different or the same as what’s going on today?

Matt Hart: Yeah, I think that when we’re certainly looking at the the first wave, so the the early Anarchist Red Cross, you had a community that was predominantly Russian. I’ll use that word, just simplify, because of the fact that it was part of the Russian Empire at that time, but, again, a lot of them were Polish or Ukrainian. We’ll just say Russian Jewish community, just to simplify it. One of the things that they were often involved in was obviously the labor movement here in the United States. You had the International Ladies Garment Workers Union that definitely had a lot of communists and anarchists as a part of its leadership and part of its rank-and-file membership. And when we’re looking at New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia, you did have a lot of folks that were involved in the labor movement, labor community. The folks who were part of the Anarchist Red Cross were also involved in the labor movements in those areas. So when I’m doing research about some of these folks, one of the things that I do see consistently is them getting arrested because of their labor activity. Then, they were also involved in the Union of Russian Workers, IWW, they were still very active. It wasn’t just that they existed here in the United States and we’re just going to support the revolutionary movements back home. They were still very active in terms of their organizing. In Philadelphia, they’re part of the Radical Library. They were still people who were continuing to organize, mostly around the labor movement.

When we’re talking about the second wave, one of the things that’s interesting to me is really what took place with the organizations in Europe, because one of the significant parts of Stuart Christie life was the trials and the accusation of his being involved in the Angry Brigades. He was tried and wasn’t convicted as part of that, but he was accused of either being a part of the Angry Brigades or at least helping to facilitate communication between the underground movements in the UK and Europe. That was the accusation. When you look at a lot of Christie’s writings, which are separate from Yelensky’s because Christie came much later, you’ll see them talking a lot about people floating through the spaces that Christie and Albert Meltzer were helping to organize. You would have a lot of the Spanish anarchists floating in and floating out, participating in ABC for a brief period, and then disappearing, and then ending up engaging in actions in Spain. Unfortunately, some of them were eventually killed because of their involvement in the anti-Franco movements. So you did have that dynamic at play. So how much they were involved in terms of stirring those pots or helping these different groups communicate? That, I think we’ll never know because unfortunately, Christy has passed on, and I’m not sure how many people are going to speak on that, but something that was there. What it was, who really knows?

Then we’ve got people like Thomas Weissbecker and Georg von Rauch, who were part of the organization, but then eventually went on to form the Haschrebellen and then joined the June 2 movement, which eventually cost them their lives, unfortunately. Both of them were killed in shootouts with police, as a part of their involvement in the June 2 movement, but they were also part of the Anarchist Black Cross. I think that was definitely a component of that generation. Then I think that it would be a mistake if we didn’t talk about Giuseppe Pinelli, who was a part of the movement and lost his life. He wasn’t involved in any of those types of underground movements, but one of the things that were significant with him was that he identified the fascist bombing campaign that was designed to place the blame on the left, on communists and anarchists, so that there would be a demand for law and order, so that way the fascists would then be able to rise back into power in Italy. He identified that, but he was eventually accused of being a participant in one of the bombings, and then was thrown out of a four-story building that led to his death. One of the significant works that he was doing was identifying this plot by the fascists who were supported by the United States or by the CIA as well. I think we’d be remiss if we didn’t at least mention him as a part of this larger scope.

TFSR: Yeah, there were connections in Spain between nascent ABC chapters and the MIL. It seems like there were a number of those sorts of things. Thank you for bringing up Pinelli. I think that’s a really fascinating story. I’ll try to put some links in the show notes to some good articles. Did you ever read Dario Fo’s book, The Accidental Death of an Anarchist?

Matt Hart: I’ve never read that, but I do actually have a lot of newspaper articles regarding Pinelli, also some of the old ABC publications from Italy around that period of time, and then obviously the “Black Flag”‘s that talked about his passing. I think Stuart Christie had actually written a book spelling out more. I think it was Christie who in The Strategy of Tension, spelled out the connections in terms of Italian state trying to associate the anarchists and the communists, mainly the anarchists, with these bomb campaigns, and even the CIA’s involvement in that whole process.

TFSR: Yeah, when I started reading through the introduction, and you keep footnoting Christie books, I told myself I’m gonna go and try to find them, this is off mic, but order myself some of his books. I tried to read Granny Made Me An Anarchist before, but didn’t get very far into it, just past where he was talking about getting jailed, and his funny way of telling the story. Yeah, I came across that. I looked at Meltzer books too, and just started looking into Cienfuegos Press books and what they had published. Christie had written a book about a specific individual in the Strategy of Tension, some fascist organizer with military connections. There are copies you can find for maybe $250 online, there’s a Kindle edition of it.

Matt Hart: When Christie was alive, I was able to get a lot of his books from him. Edward Heath Makes me Angry I think it’s one of them.

TFSR: Franco Made Me an Anti-fascist?

Matt Hart: What’s funny is a lot of these are repetitive in terms of the writing. I mean, he’s copied and pasted a lot of his stuff, but in The Heath Made Me Angry one he actually goes in a different direction with a lot of the stuff and talks not so much about Angry Brigades, but the Anarchist Black Cross stuff, and more about the connections with the anti-Franco anarchists that were going into Spain, and the fact that they were connected with the Anarchist Black Cross. He would always say, though, that they weren’t ever members of ABC. When I asked him about somebody being a member of the Anarchist Black Cross, his response to me was that they weren’t, there wasn’t a membership. It didn’t work that way. He said that people just came in and did the work. He was very clear, he was very adamant about the fact that there was no membership to the organization.

TFSR: The 2007 AK Press Christie’s book is pretty thick. Maybe it was a compilation of a few of those “People Made Me Feel This Way” books he had written beforehand.

Matt Hart: Yeah, I don’t think I have that one. I’d have to look, have to see it.

TFSR: When I get it on the seventh I’ll let you know. Okay, I won’t keep you much longer. I just had two more questions about the Russian Revolution. A lot of people who were in the international communities that were doing prisoner support kind of assumed that the czarist repression had ended and that there was a release of political prisoners. Then people in the international community started getting news about the arrests of dissidents, of opposition to the Bolsheviks as they centralized power. That seems pretty pivotal, it caused the ARC to reform itself. When they were organizing in exile, in response to the renewed existence of political prisoners in their homeland, organizing publicly meant people being concerned about not only Bolsheviks in the US coming and trying to disrupt or attack the events as being undermining the revolutionary spirit of Russia or whatever, but also, there was in the US a terrible anti-communist, anti-anarchist sentiment, after the Palmer Raids, after the deportations of tons of radicals, as well as the US getting involved in the Civil War against the various revolutionary forces there. Can you talk about the challenge of this position competition within the radical support world, and how this educational effort about the realities within the Soviet Union was received at this time following the 1917 revolution and Lenin’s grasp of power?

Matt Hart: First and foremost, to your point, when the revolution happened and you had the political prisoners all being released, I think it’s a very important belief to begin this conversation with was that Russia has now become sort of workers’ paradise if you will. That there we have a situation where you actually have a free worker state. And so I think within a lot of people’s hearts, including a lot of the anarchists and members of Anarchist Red Cross who went over there under the belief a new society was changing, I think there was a lot of hope that existed. And I think that you need to look at what was going on in the United States at that time. You had a Red Scare taking place. You had mass arrests of anybody that was considered very apropos that were going on at this time.

If you think about it, people who were having radical politics and were considered foreigners were now being swept up and deported. So you had this fear and anxiety that existed in the United States at that time, but you also had this vision of what was taking place in Russia that it was a free worker state, and a workers paradise, if you will. There are a couple of books, The Guillotine at Work, Vol 1: The Leninist Counter-revolution (by Gregori Maximov – Ed.) is a great document that provides sort of the history of some of the repression that was going on at the time in Russia. We start seeing things change, where anybody who wasn’t consistent with the Bolsheviks party line, you saw being incarcerated, and eventually some of them killed. Even though there were attempts to get the word out, including things like that there was a prison strike called the Taganka prison strike. There were attempts to get the word out to the larger international community.

It really wasn’t until Berkman and Emma Goldman were able to leave Russia and from Berlin basically wrote an appeal to the larger movement, saying that this wasn’t exactly what everybody thought it was. I think that that was where something began to change, although it took a number of years for people to truly believe that what they were hearing actually had merit. At that point, when you look at Yelensky and some of the writings, he brings up a couple of points. One, looking at the current atmosphere of the US, together with that belief that Russia was a liberated area, a free worker state. That was hope, and so a lot of people were grasping onto their hope and didn’t want to believe the information that was coming out. That definitely had an impact, even taking aside the Bolsheviks and their propaganda machine here in the United States, whenever there was a positive narrative that was being sort of put out in Russia, it became much more accepted because people didn’t want to believe the other narrative that things weren’t as great as what we were hoping for.

So you’re dealing with this concept of grabbing onto that hope as much as possible, and not wanting to give it up, and trying to convince people that, no, that’s not true. That became a very difficult thing to do, to try to organize support when you have people who aren’t willing to believe that what is being said is true or has merit. Then you also obviously had people that were here to disrupt or challenge any narrative other than what was being said by the Soviet Union by Lenin and the Bolsheviks. You had them in meetings, constantly shouting down individuals who were challenging the Bolshevik narrative as being counter-revolutionaries, as people who were doing the work of the United States government. They were counter-revolutionaries, or not revolutionaries at all.

It took several years before any type of significant support work was able to take root. New York Anarchist Red Cross, I think was formed I want to say 1924 or 1925. Chicago had formed, I think a few years earlier, at least some type of support network. So it took some time for things to really gain momentum. It was really probably the letters of Russian prisoners that were published by New York that was when things began to change. But I forget what year that was actually. That might have been 1925 as well, I’d have to look. It took a long while before that support network could really gain roots, and it never could before. I would say that fundamentally speaking it never really had the traction that it did earlier on. You only had technically two Anarchist Red Crosses that were formed, and besides the support from the Jewish Anarchist Federation, which did provide a lot of support, there weren’t a lot of people doing that work.

TFSR: What do you hope that anarchists in general and those involved in anti-repression work in particular will take from this book? You’ve already mentioned the “What are we fighting about amongst ourselves? What impact does that have on prisoners?” for instance.

Matt Hart: At the end of the day, I think the main focal point for me is debate and discussion in our movement. I think it needs to be something that’s a vital part of who we are as a community, to have discourse, to have discussions, to challenge ourselves. I think one of the things that this book does say, is let’s make sure that at the end of the day, our divisions aren’t things that undermine our movement or our missions, and what we’re trying to achieve. I think this book does highlight what happens when you have these divisions, and they do get in the way and ultimately, how it affects people especially when it comes to the prison support community. They can affect prisoners in a much more significant way, including death. And so I do think ultimately if there’s anything that people can walk away with regarding this book, it’s the importance of making sure that our divisions or our differences don’t get in the way of our work.

TFSR: Finally, what are you working on now?

Matt Hart: Now that PM and N.O. Bonzo, (thank you both for helping me get my butt moving), have since helped me with getting this project together, and we were able to accomplish this all together, I’m now working on getting my notes and all of my writings together to possibly work on another book about the history of the Anarchist Red Cross and some of the stuff that wasn’t included, or at least some of the stuff that was lost in the footnotes, to try to bring that out and as part of this process. Even still, today, we’re constantly finding new information about the Anarchist Red Cross. So hopefully, with that, we can see something published sometime in the future, in terms of the next book about the Anarchist Red Cross.

TFSR: Cool, Matt, thank you so much for having this conversation. Is there anything that I didn’t ask about that you wanted to plug.

Matt Hart: Being a member of the Anarchist Black Cross, I would argue that it’s critical to support our prison comrades who come from our community. So if you can, I strongly encourage you to reach out to political prisoners, write them, and support them. Obviously, I’m going to encourage folks to buy the book. All proceeds of the book go directly to supporting political prisoners. So none of it goes directly to me. I don’t profit from it by any stretch of the imagination. That all goes to supporting the Warchest. All those funds go directly to support political prisoners. If you’re interested in doing support work, check out abcf.net.

TFSR: Cool. Thank you so much, and I hope you have a good bookfair and a good June 11.

Matt Hart: Likewise, my friend. Thank you. Bye.