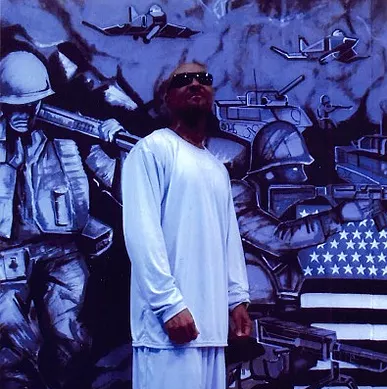

Unity And Struggle Through The Bars with Mwalimu Shakur

This week on the show, you’ll hear our conversation with Mwalimu Shakur, a politicized, New Afrikan revolutionary prison organizer incarcerated at Corcoran prison in California. Mwalimu has been involved in organizing, including the cessations of hostilities among gangs and participation in the California and then wider hunger strikes against unending solitary confinement when he was at Pelican Bay Prison in 2013, helping to found the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, or IWOC, Liberation Schools of self-education and continues mentoring younger prisoners. He was in solitary confinement, including in the SHU, for 13 of the last 16 years of his incarceration.

- Transcript

- PDF (Unimposed)

- Zine (Imposed PDF)

- Mwalimu’s “History of Black August: Concept and Program”

For the hour, Mwalimu talks a bit about his politicization and organizing behind bars, his philosophy, Black August, the hunger strikes of 2013, the importance of organizing in our neighborhoods through the prison bars.

You can contact Mwalimu via JayPay by searching for his state name, Terrence White and the ID number AG8738, or write him letters, addressing the inside to Mwalimu Shakur and the envelope to:

Terrence White #AG8738

CSP Corcoran

PO Box 3461

Corcoran, CA 93212

Mwalimu’s sites:

To hear an interview from way back in 2013 that William did former political prisoner and editor of CA Prison Focus, Ed Mead (before & after the strikes), search our website or check the show notes.

Other Groups Mwalimu Suggests:

- Initiate Justice: https://www.initiatejustice.org/

- Critical Resistance: http://criticalresistance.org/

- California Prison Focus: http://newest.prisons.org/

- Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC): https://incarceratedworkers.org/

- Malcolm X Grassroots Movement: https://freethelandmxgm.org/

- Revolutionary Intercommunal Black Panther Party: https://www.facebook.com/RIBPP

- Jailhouse Lawyers Speak: https://jailhouselawyerspeak.wordpress.com/

- San Francisco Bay View National Black Newspaper: https://sfbayview.com/

- True Leap Press: https://trueleappress.com/

Continue reading Unity And Struggle Through The Bars with Mwalimu Shakur