Gord Hill on Art and Resistance

Gord Hill is an indigenous author, anarchist, antifascist and militant, a member of the Kwakwaka’wakw nation living in so-called British Columbia, Canada. Gord is also graphic artist and comic book author who most recently published The Antifa Comic Book, out from Arsenal Pulp Press, and runs the website Warrior Publications and sometimes publishes under the nom-de-plume of ZigZag.

For the hour we speak about his writings documenting indigenous resistance history in the so-called Americas (mostly with a focus on Turtle Island), antifascist organizing, intersections of indigenous struggle and anarchism and critiques of Pacifism (see Gord’s “Smash Pacifism” zine). Some of the points of resistance that we cover include Elsipogtog (Elsipogtog in 5 Minutes video at sub.media), Idle No More, The Oka Crisis (“The Oka Crisis in 5 Minutes” video at sub.media), Stoney Point/Aazhoodena (another 5 minutes video by Gord), Gustafsen Lake (we didn’t talk about but another 5 minute video), the Zapatista Rebellion and the Unist’ot’en Camp resistance to pipelines in so-called B.C.

Sean Swain: [ 00:033:55 ], Gord Hill [ 00:11:27 ], announces at [ 00:57:29 ]

Rayquan Borum Trial Update

In a brief and sad update to last week’s interview on the case of Rayquan Borum, we’d like to read a statement from the fedbook page for Charlotte Uprising:

We are deeply saddened to report that Rayquan Borum has been found guilty of possession of a firearm and second degree murder with him being sentenced to 25/26 years in a cage.

We knew it would be difficult to receive a fair trial in the same court that allowed Officer Randall Kerrick to walk free for the murder of unarmed Jonathan Ferrell. We know the police will continue to kill Black and brown folks and escape accountability.

We suffered extreme suppression from the judge from the start of the trial. Even though the medical examiner testified there was a 51% chance that ANYTHING else killed Justin Carr, Judge Hayes would not allow any testimony naming the police. Of course, it is far easier to scapegoat a random Black man than to launch an investigation into the same police force that killed ONLY Black people in 2015.

We also know that Justin Carr would be alive were it not for the Charlotte Mecklenburg Police Department murder of Keith Lamont Scott (no trial for that officer, of course). We know that the Mecklenburg County Courts disproportionately sentence Black and brown bodies to time in cages. We know that CMPD disproportionately arrests Black and brown folks. Black people are 30% of Charlotte’s population and make up about 70% of the jail population.

Heinous.

We know that this is the American Way. In response, we will continue to rise up and resist this colonized nation and work toward building a more decolonized world, for all of us.

Forward, together

#CMPDKilledJustinCarr #CagesFixNothing #FreeThemAll #CMPD #RayquanBorum #MecklenburgCounty #NoMoreKIllerCopsOrJails

A few house keeping notes about the show. We’re happy to announce that The Final Straw is now available on the Pacifica Radio platform for affiliate stations to pick up more easily. If you, dear listener, live in an area where we aren’t on the radio but there’s a community station that airs programming from the Pacifica Network, you now have a WAY easier IN to bug the station’s programming director with. If you want us on your airwaves, check out our “broadcasting” tab on our website and reach out to a local radio station. If you have questions or want help, reach out to us and we’re happy to chat. We hope to have a some more terrestrial broadcast stations to announce soon.

Actually, yah, that was the only note. Tee hee. Otherwise, if you want to hear me, Barchive is linked up in our show notesursts, Dj’ing a 2 hour set of punk, goth and electronica on AshevilleFM, an archive is linked up in our show notes that’s available until March 12th.

Announcements

Asheville Events

If you’re in the Asheville area, there’re a few events coming up on March 16th of note. At 11am at Firestorm books, a participant in the Internationalist Commune, a self-organized collective in Northern Syria, will join us for a video chat about the revolutionary movement to transform Kurdish territory into a stateless society.

Later, across town, there’re a couple of Blue Ridge ABC events at Static Age on Saturday, March 16th. From 3-5pm there’ll be an N64 Super Smash Brothers tournament with vegan philly cheese steaks and fries available, and then from 9pm onward an antifascist black metal show featuring Arid from Chicago, plus local bands Rat Broth and Feminazgul.

Then, a reminder, that on March 22nd at the Block Off Biltmore is a benefit for info-sharing between Southern Appalachia and Rojava. The event will include a discussion, a short documentary showing, vegan desserts and nice merchandise. For more info, check out the flyer in our shownotes from March 3rd, 2019.

And now a couple of prisoner announcements

Chelsea Manning Imprisoned

U.S. Army whistleblower and former Political Prisoner, Chelsae Manning, has been jailed for criminal contempt for refusing a subpoena to participate in a Federal Grand Jury in Virginia concerning her 2010 disclosures to Wikileaks of U.S. drone killings of civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan. A support committee called “Chelsea Resists!” has been set up and updates will be coming from the website xychelsea.is and there’s a fundraiser up at actionnetwork.com for her as well. We hope to feature members of her support as well as former Grand Jury resisters who’ve been on this show before in an episode soon. You can write to Chelsea at the following address:

Chelsea Elizabeth Manning

AO181426

William G. Trusdale Adult Detention Center

2001 Mill Road

Alexandria, VA 22314

Some quick guidelines to keep her safer while writing are in the show notes

- Address your letter exactly as shown above

- send letters on white paper

- use the mail service to send letters

- include color drawings if you’d like

- sparingly send 4×6 photos, as she may only keep 10 at a time

- Do not send cards, packages, postcards, photocopies or cash

- Do not decorate the outside of the envelope

- do not send books or magazines

Exonerated Vaughn 17 prisoners transferred out of state

As the cases proceed against the Vaughn17, 17 prisoners on trial in Delaware for a prison uprising following the election of Trump as president, an uprising sometimes compared to the Lucasville Uprising, repression continues.

The uprising was as follows: prisoners took over Building C at the Vaughn prison in Smyrna, Delaware, and took three prison guards and one prison counselor hostage. Demands issued during the hostage standoff included that Delaware Governor John Carney investigate poor living conditions at the facility. One correctional officer who was taken hostage, Steven Floyd, would later be found dead after police re-entered the facility. The case can be followed at vaughn17support.org as it enters it’s third trial group. A few words from the support site note the continued repression of some of the court-exonerated prisoners:

The State of Delaware retaliated against defendants in the Vaughn uprising trial last week, by moving them out of state to Pennsylvania.

Kevin Berry, Abednego Baynes, Obadiah Miller, Johnny Bramble, Dwayne Staats, and Jarreau Ayers were all transferred to solitary confinement at SCI Camp Hill, a maximum security facility. They joined Deric Forney, who was transferred weeks earlier in January. Berry, Baynes, and Forney have all been fully acquitted on all charges.

“It’s unusual to move prisoners with short terms left in their sentence out of state,” said Fariha Huriya, an organizer working closely with Vaughn 17 prisoners. “They’re being held in solitary confinement, with no showers, no access to commissary, and limited phone calls. It’s the same inhumane conditions that they faced at James T. Vaughn.”

“The State’s vindictiveness will cost them,” said Betty Rothstein, who also organizes with the prisoners. “The Vaughn 17 have resisted these charges, and will continue to resist and expose the corruption of the DOC and abuse on prisoners.”

There are nine defendants who are still awaiting trial. New trial dates for groups 3 and 4 are scheduled for May 6th, 2019, and October 21st, 2019.

. … . ..

. … . ..

Transcription:

TFSR: So I’m joined on the phone by Gord Hill. Mr. Hill, who sometimes is published under the pseudonym Zigzag is the author and artist behind The 500 Years of Resistance Comic Book, The Anti-Capitalist Resistance Comic Book, and recently The Antifa Comic Book, all out from Arsenal Press. Gord Hill is also the author of 500 Years of Indigenous Resistance, out as a booklet by PM Press, and Smash Pacifism: a Critical Analysis of Gandhi and King published by Warrior Publications. Could you introduce yourself a little further for the audience?

Gord Hill: Sure. My name is Gordon Hill, as you said, I’m from the Kwakwaka’wakw nation and my territory is located on the northern part of Vancouver Island. I’m currently residing in British Columbia. And I’ve been doing graphic artwork and been involved in different social movements since the late 1980s.

TFSR: How did you get radicalized? How did you get into political activism and writing?

GH: Me and my mother moved into Vancouver in the late 1980s, or towards the mid 1980s, and I got introduced into the punk scene. And it was pretty active at the time in Vancouver, and it was a fairly political scene as well, so there was a lot of anarchist punks. So that’s how I became kind of politicized. And then after that, I just became involved in different solidarity groups, starting with an El Salvador solidarity group. And yeah, just being involved in these different movements at the time, and that’s basically how I became more radicalized.

TFSR: And it seems like it would have been a really fascinating time for a really exciting time to be getting involved in anti-colonial movements and struggles as well, which you kind of cover a little bit of in 500 Years of Indigenous Resistance. Can you talk about what it was like to be like a young Indigenous activist during the time when, like the Oka uprising happened or when the Zapatista uprising was happening? And what thoughts were occurring for you and sort of what conversations were happening in your communities?

GH: Oh sure, yeah. So when Oka 1990 happened I was pretty much involved in the anarchist movement at that time. That’s all I was doing. Then when Oka happened, that kind of inspired me to look back at my own Indigenous roots and my ancestry and then that’s when I started becoming more involved in Indigenous resistance movements.

In 1994 when the Zapatista uprising occurred, I was kind of involved in both. I was involved in the anarchist movement, I was still fairly active, and in the Indigenous movement as well. Oka was very important for me personally, but it was also very important for Indigenous people across the country, because it really rekindled the warrior spirit of Indigenous peoples, the fighting spirit. There was a lot of activity that emerged after Oka, a lot of little blockades and that were happening, especially here in British Columbia. So that was all really new to me, it was very exciting.

With the Zapatista uprising, it was also very important because at that time in 1989-1990, you know, the Eastern Bloc had collapsed, and the Berlin Wall came down. And, you know, especially in Germany and Russia, there was this massive resurgence of fascist activities and attacks and violence and murders and whatnot. There was this sense of like, the triumphalism of capitalism emerging from this struggle-against-communism kind of thing. I mean we didn’t have any real respect for the USSR or anything because it was just like this massive system of its own.

It was kind of demoralizing at the time because also a lot of movements and groups were affected by the demise of the Soviet Union, because they were actually like a source of funding for some of the guerrilla groups in Central America and whatnot. Overall there was just this kind of demoralization. I think that it had set in, to a certain degree throughout the left, and it also affected the anarchist movement to some degree.

The Zapatista uprising was really important at that time because there wasn’t a whole lot of inspiring types of movements or anything like that happening at a time, so the Zapatistas were really important in that way. And here in North America, they really kind of focused people’s attention — and I think it took a while, maybe a few years — because they were addressing the North American Free Trade Agreement, they were addressing neoliberalism. They were like the first big movement that really was talking about neoliberalism. And then that kind of analysis and their methods really inspired social movements around the world in North America as well. I think they kind of contributed to the rise of the anti-globalization movement in the late 90s, and then the World Trade Organization protests in 1999. But um, yeah, that was how I saw those events Oka and the Zapatista uprising. They’re very important, very inspiring.

TFSR: Yeah I know for myself as someone who’s a little bit younger than yourself, but not much, when I was learning about the Zapatista uprising — probably initially through things like music by Rage Against the Machine and following research down little rabbit holes off of that — their ability to their ability to speak and create art beautifully, and create spectacle, and sort of just instigate amazing discussions was astounding. They were able to grab a hold of the mediums of the internet and satellite technology, live broadcasts from the middle of the jungle, and these amazingly written communiques that just grasp at the heartstrings of liberatory minded people around the world. A lot of different people have looked at them and said, “these people are ours, these people are like us.” I know a lot of anarchists have done that. The Zapatistas, as far as I know, have never called themselves anarchists. They’ve refrained from calling themselves a lot of things. They just kind of say they practice Zapatismo. But that kind of makes me think about your use of media also, and the radical media like this 500 Years of Indigenous Resistance. Can you talk a little bit about this? This was originally published by Oh-To-Kin?

GH: Oh, the book that’s been published by PM Press?

TFSR: Yeah.

GH: I originally wrote that in 1992. It was published in our newsletter I was creating at the time, Oh-To-Kin, meaning strength from our ancestry. And that was kind of like after the Oka thing, because that’s when I really started focusing on my ancestry and Indigenous resistance movements. So at that time in 1992 the 500 year mark of the invasion of the Americas was coming up and I just really wanted to understand the history of what had happened in that time period and whatnot. I started researching it and that ended up being the article that I published in the newsletter, and then eventually PM Press republished it, yeah.

So that was just kind of like my own thing at the start. I just wanted to understand the history and know what had happened, and that’s what I ended up doing. But 1992 was actually a big year because there was this big anticolonial mobilization that occurred in a lot of different cities across North America, and of course, all through South Central America. So it was a big year. It was just after a couple years after Oka and it was kind of a pretty important time. That’s how that article came about.

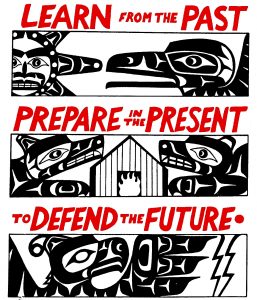

TFSR: It’s interesting, you said that you were doing your research into your past and into your heritage, and you produced this thing that you then share with other people, and — what I’ve always been struck with by your artwork, and by your writing is how simple you present these huge historical things. Like, between using imagery and words that are…they’re not dumbed down, they’re just upfront, they’re just clearly explaining what’s going on. You do a really good job of making things really graspable. I think that’s something I really appreciate about that book, for instance.

GH: It’s one thing I’ve always tried with the writing. I might not have been very conscious of it at first with the writing, but a lot with my artwork I always tried to be really clear to make sure that other people can understand, so there’s not a lot of vagueness or, you know, easy to mistake what the intention of the art or the writing is. So it’s part of trying to communicate effectively different ideas and whatnot. Because actually with that “500 Years” article I had been reading a lot of Ward Churchill at the time. He was always inspiring me to really research and take footnotes and stuff, but one thing I did find about Churchill’s writing is that it’s very academic and I found it difficult to read a lot of texts at the time. So when I was doing my research I would basically try to make sure that I rewrote stuff so that I could understand it, and then those notes would contribute to the article. So it was kind of like an organic way for me to, you know, understand what was being said. And then I just transferred over to when I started to organize articles for publication.

TFSR: How did you start getting into graphic graphic art and like mixing that with the words? Like, were there any inspirations? Or were there any comics that you read growing up that really spoke to you?

GH: Yeah, I used to read all the Marvel Comics, like Spider-Man, Fantastic Four, Conan, and all that stuff. Me and a lot of my friends, we were always trying to do comics, like drawing comics and stuff like that. And I would continue on and off throughout the years even through my teenage years trying to do comics and stuff. But my problem was I was never really the story writer, so I couldn’t make up stories about different people or heroes or whatever. And then I started doing graphic art for publication because when I started getting involved in different solidarity groups and different movements I would always contribute artwork to posters or logo designs, or banners. And then I would still once in a while maybe think about doing comics. That’s how the “500 Years” comic came about; I first started doing like two or four page comics about something that I thought was important that could be easily reproduced on a photocopy machine and distributed at conferences, or people could take them and make more copies when they got back to wherever they were coming from.

So that’s how I started to assemble all these short little stories that I was republishing — like photocopying and distributing — then I had a collection of them. And then it just eventually led to the comic book which started out as a collection of short comics I was self publishing.

TFSR: I think I remember first seeing your artwork on materials meant to draw people to protest the Olympics, but I’m having trouble remembering which ones they were. They weren’t the 2010, right? There was like a decolonial element to resistance to the Olympics in BC, in the mid-2000’s, right?

GH: Yeah, I think from about 2007 till 2010 that’s when I was involved in the anti-Olympic movement there, and I was doing a lot of artwork.

TFSR: Yeah, it’s definitely iconic. So your most recent book, The Antifa Comic Book is very, very well researched, and covers a lot of history and geography. Can you talk about what inspired this and like, who the audience is for that comic?

GH: Well, the inspiration was actually from the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, where Heather Heyer was murdered, because that kind of motivated Arsenal Pulp Press, because after that they actually approached me about doing a comic. I said definitely, yeah, that’d be awesome. Because I’ve been involved in Anti Fascist stuff in the 90s and I’ve always kind of kept track of the rise and fall of the fascist far-right movements and whatnot. And then with the resurgence of the alt right over the last few years, I was kind of tracking it. So yeah, they were the ones who asked me if I’d be interested in doing it and they wanted it to be published fairly quickly because there was a sense of timeliness connected to it. And so I started research again and took several months of just working all through the day to get it done. But yeah, I was pretty happy with it and I think they did a really good job publishing, the paper, the color and stuff. I’m pretty happy with it.

TFSR: Did you find it difficult at all talking about the differences between how fascism has arisen in Europe in these relatively homogenous countries that have been settled for 1000s of years, versus the settler colonial situation on Turtle Island, and the way that the far right and white nationalism comes up in that different scenario?

GH: I didn’t find it difficult, no, because it’s just researching certain movements in a particular time in history, at a certain geographical location. Like the Italian Fascist movement, you know, I researched that and developed this storyline of that history or whatever. Then with North America there are definitely certain histories that need to be included if you’re doing a history of the fascist and far right movements in the US, and that includes the Ku Klux Klan. So, you know, that’s not a fascist group, so with the North American section it was different from the straightforward fascist movement you have in Italy, or Germany, or even Britain.

I mean and there’s some things I don’t think I got it into the comic. Talking about some of the far right groups and the participation of people of color in some of these groups, like Patriot Prayer on the West Coast here and down in Washington state and Oregon. They’re not just white supremacists, white nationalists, they’ve got these people of color involved who are obviously far right. And then you even have like these neo-Nazi Mexican skinhead gangs, like in the New York attack with the Proud Boys, after the Gavin McInnes speech where there was the brawls in the streets. I mean, there was a number of the participants that were from this neo-Nazi Mexican skinhead gang. So in the US it’s actually a more diverse kind of far-right movement and split.

One thing I talked about when I did the comic book tour, the potential in the US, there is a potential that you have a multinational far-right fascist movement as well as just the strictly white nationalist kind of racist movements. And that’s kind of different, and that’s obviously because of the colonial history of North America and all that entails and the differences and stuff like that. But I mean, practically, I didn’t really find that much different. It just came became a little more complicated with North America, because I also have the update, “okay, the Ku Klux Klan in the 1970s, the Ku Klux Klan in the 1980s” because they’re one of those groups that’s always reappearing even if they’re always just a small kind of weird movement [laughing at the Klan]. They’re always reappearing throughout the history of the far-right in North America.

TFSR: I was really surprised to find out from the graphic novel about the history of the Klan in Canada. Like, I guess considering the shared ideological roots and underpinnings of white, Protestant, manifest destiny or whatever, and male supremacy, it kind of makes sense. But I thought it was just a US phenomenon.

GH: Yeah, no, it was quite large and as I have in the comic it was quite large in some parts of Canada, including on the prairies, and they were working with the highest levels of at least the provincial governments at the time. And it was similar as in the US where you had governors that were also members of the KKK. Mayors and police and whatnot. Yeah, and the main difference was really that the KKK in Canada was still very pro-British, like pro-monarchy, loyalist type of politics as well, but otherwise, fairly similar.

TFSR: Another publication that you made — which is not graphic heavy, but which I thought was really provocative and interesting when it came out — was Smash Pacifism. Starting with the image of the black bloc character smacking Gandhi on the cover. It’s a really, really well researched publication and it creates some really interesting and compelling counter-narratives, to the presentation of those two people and of the roots of pacifism, and the popular culture and predominance of pacifism in activist circles. What all inspired that book, and what sort of reception did it receive?

GH: Yeah, that was kind of inspired by the interactions with pacifist at a lot of rallies, and just seeing this kind of debate, definitely since the WTO protests in Seattle — but I mean, of course, this goes back decades, it goes back to the 20s, and 30s or whatever — but just from my personal experiences of just getting really frustrated with the pacifists, and how they revise history to suit their argument. That they have a morally and tactically superior method of waging resistance. So that’s mostly where it came from.

I’ve also read Gelderloos How Nonviolence Protects the State, which is an awesome book as well. It’s a really well written argument against pacifism. And then I’d also read Ward Churchill’s Pacifism as Pathology. Those books inspired me because I wanted to look at the root of these things. which I’ve identified as Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, because they are like the figureheads of pacifist nonviolent movements today. And they’ve always been kind of presented as the model of how these kinds of campaigns are to be carried out. And so when I started researching it, and looking into it, I found there’s all these different things about Gandhi, and some of these campaigns and his collaboration with the British and all this kind of stuff.

And similarly, with Martin Luther King and the whole Civil Rights campaign. I mean this kind of hypocrisy, like they’re telling everyone, “you got to be nonviolent”, but they themselves are armed or have armed bodyguards to protect them. And just that type of hypocrisy [laughs] that kind of tinged the whole writing too. I was just like “Oh, my God, I can’t believe they get away with this”. That’s kind of how I felt. So that was how that booklet came about [chuckles].

TFSR: Yeah, those are, those are some really good essays that you referenced there, the How Nonviolence Protects the State and Ward Churchill’s Pacifism as Pathology. I remember reading this zine years ago, probably like 2005 or 2006, called — maybe I won’t remember the name of it — the author’s name was Ash and Ruin, and I remember them pulling from both of those titles and just feeling really right on about what they were having to say. It also kind of, as a student of history, I think it does a major disservice to the complexity of — besides enabling people to let down their guard when it comes to how power actually does operate in the world, and how the state reacts to people who are presenting alternatives —- it also does a disservice to the complexity and the struggles of the individuals that actually were involved at the time. Let alone, I’m sure for whatever it’s worth, I think the whole deifying of those two characters weakens everyone overall —

GH: Oh, totally.

TFSR: — I’m sure Martin had a lot of internal conflict about that. Also, he said at one point, you know, “as a child of God, I have a right to defend myself, as do we all” like when he was pushed that way by Robert F. Williams, I think in a debate.

GH: Yeah. Well a lot of pacifists were like…Gandhi would be the same. Gandhi was, I think, far worse in that respect because he was so opportunistic, and he would say one thing and then a little bit later say another thing. He’s kind of like the Bible, you can find a lot of stuff if you’re looking for it. Like Ghandi justifies self defense, and you’ll find a quote about that, and then you’ll find another one where he absolutely condemns any kind of self defense and stuff like that.

TFSR: Or finds themselves siding with the British occupiers or crying about police who end up dying in the middle of a riot, or what have you. Or saying that the Jews should practice nonviolent resistance and they would end the Holocaust or whatever.

GH: Yeah, yeah. There’s a lot of kind of ludicrous stuff [chuckles].

TFSR: Can you talk a little bit about Warrior Publications, and over the last few decades, the resurgence of Warrior Societies in North America?

GH: Warrior Publications is where I started self publishing my articles, graphic posters or whatever. Started in like 2005 or something. I put out a few issues of a magazine just called Warrior and published different zines, like Smash Pacifism or History of Blockades in DC and stuff like that. Then 2007 or so I started doing the anti-Olympic website, no2010.com, which doesn’t exist anymore, of course. But after 2010, I think around 2007 I had set up a Warrior Publications website by a friend of mine. And then a few years later, I revamped it after the Olympics. And so I’ve just been maintaining the website ever since then. So since around 2009, I guess I’ve had this website. And it’s mostly what they call a “news aggregator”, because I’m just reposting articles mostly from corporate news, but also like alternative news, radical news sources as well. I sell T-shirts through the website as well. That’s basically what Warrior Publications is.

As far as the resurgence of Warrior Societies, after Oka 1990 you did have this kind of resurgence of Warrior Societies, but it’s more like when there’s some communities that have a stronger kind of history of resistance. And like the Mi’kmaq are an example, outside of the Mohawks, which we know have maintained some type of Warrior Society since the 70s, right? But other communities like some of the Mi’kmaq had a Warrior Society which mobilized during the campaign in Elsipogtog against the fracking in New Brunswick a couple of years ago. Then there were other groups that kind of came and went over the years. But, I mean, it’s more like you’ve had a resurgence of a Warrior Society culture. And that comes and goes, depending on the times, right?

Just before the Elsipogtog Anti-fracking campaign, which saw a lot of militant actions and half dozen police cars were set on fire, and this kind of militant stuff. But just before that we had Idle No More, you know, which was really pushing nonviolence and this kind of legalistic approach to social change. That was a pretty significant movement here in Canada, thousands and thousands of natives were mobilized into the streets and you’re rallying and all this type of stuff. So it really got native people coming out, so that’s really a strong indicator that there’s a lot of potential there.

But of course, the movement was very legalistic and very nonviolent in its whole approach, and they failed ultimately in their goal. They were mostly opposing a Bill C-45, which contained some changes that we’re going to lift protections for some waterways and stuff like that. So that was kind of why this Idle No More thing started, and then it became a big movement here. But it also kind of pacified the Indigenous movement overall, because it kind of set this tone that you have to be super nonviolent.

Then Elsipogtog was really important, because then you had a kind of a resurgence of the warrior kind of method or whatever, Warrior Society type of actions. So Elsipogtog was very important and then of course, they were victorious, right? They stopped the exploratory drilling looking for fracking sites, they stopped the whole fracking process. And as a result of this massive struggle, New Brunswick, the provincial election the next year, which was seen as basically a moratorium on fracking, you know, the party that opposed the natural gas fracking won and there was a moratorium put on fracking. And it’s still in existence. So it was a big victory for Mi’kmaq and involved an important contribution from this Warrior Society. And so that was really important.

I don’t really see like a whole lot of Warrior Societies though, right? But I see it in terms of the Indigenous social movement, how it rises and falls, and there’s actions at times that inspire things, and then there’s other things that come along that set a different tone. So this is something I think that’s always going on. But, you know, right now the most recent thing has been the Unist’ot’en, the defense of Unist’ot’en against the natural gas pipeline they’re trying to put through. And there’s a lot of solidarity actions that are have occurred across the country in that, but I mean, right now, the police are there and the construction work is being done right now. They’re clearing the pathway or whatever, and doing all their preparatory work for the pipeline. So this is what is going on right now, but if there was a lot of Warrior Societies you would expect them, there’d be a lot more actions, you know what I mean?

The Warrior Societies that are in existence, they’re kind of more organic, they’re not like military formations as such. And in a lot of cases they just kind of come together for a particular thing, action or whatever, campaign or something like that. So that’s how I see — with the exception of I think, perhaps the Mohawk societies, they might be more organized and existing as a group — but in a lot of communities, you don’t really have an active Warrior Society as such. There are a lot of members of the community that would step forward and carry out that role if it was necessary, and I think a lot of communities are like that.

TFSR: Looking ahead, are there any inspiring movements — like you mentioned, the Unist’ot’en camp, and as you said, I think that based on their statements that they made a practical decision to not try to militarily resist the RCMP at that moment, because they were outnumbered, outgunned, and the RCMP seemed to act with a total disregard for human safety and dignity, as is their practice. But like, are there any other inspiring points of resistance or dissent on the ground? In terms of resisting the settler colonial project that you’re inspired by or that people should be paying more attention to?

GH: Well there’s a lot of struggles going on around the country. But the ones that have a much bigger impact, and that you can say are inspiring…those…you can’t really predict those. I mean, I don’t see one. But you know, there’s things that emerge. There’s a lot of different kinds of struggles, a lot of them are really localized. Like here in BC, my people, the Kwakwaka’wakw, have been involved in a struggle against fish farms and they’ve had a big impact. Most of the fish farms are going to be phased out now in a few years, and that’s great. You hope that they have a victory like this, because it’s to protect the wild salmon that are here, that’s stocks are dwindling, and stuff like this. But I mean, to me, I’m not super inspired by that because the methods by which it was achieved are really legalistic, and there was a political party that made this decision and announcement. So to me, it’s not coming from the autonomous grassroots type of thing.

The most inspiring example of that that I always try to share with people as an example of successful militant resistance is Elsipogtog. And that’s a few years ago now. So that’s the type of movement that inspires me, because, you know, it’s totally grassroots, they don’t have a lot of money. And I compare it to the Dakota Access Pipeline campaign which I know drew in like thousands of people and a lot of people were probably radicalized through their involvement in that struggle. So it’s a very important historical struggle. But compare it to the Elsipogtog campaign, which was successful, which contrasts with the Dakota Access Pipeline campaign, which had you know, thousands and thousands of people involved, big name celebrities, millions of dollars were involved in it. And they were ultimately defeated. Then I compare it to Elsipogtog, which was a much smaller, few communities involved, very grassroots, they don’t have very much money but they had the fighting spirit and the will to resist. And they use the diversity of tactics and we’re ultimately successful. When I compare Dakota Access, like I mentioned, they had big name celebrities, lots of money, very strict, nonviolent code, when there was militant resistance emerging there, there was a lot of effort made to subvert the militants and derail their efforts.

So, yeah, that’s the type of movement that inspires me. And I mean I don’t really see one right now. But also right now in this time in my life, I’m actually doing a lot of work to support my family and stuff like that, so I don’t have a lot of time to just be tracking all of these different little movements and stuff. So that’s kind of where I’m at right now, in terms of my awareness of a lot of what’s going on. I mean, even my website, I have kind of slowed down in my posting of articles because I just don’t have as much time or energy right now.

TFSR: That makes a lot of sense. So I’m always curious, when I get a chance to talk to people who are Indigenous and who are anarchist, in my experience, over the last 10-15 years I’ve heard more and more anarchists actively engaging with concepts of settler colonialism and with ideas, at least, of decolonization. And as someone who is anarchist and Indigenous, I would love if you could share a little bit about what you think anarchists could learn from Indigenous sovereignty struggles, and if there’s anything pushing towards decolonization that you think we other anarchists should learn, or pay attention to?

GH: Oh, the way I look at it is like, you kind of have two different movements. So you have an Indigenous movement, and an anarchist movement. And Indigenous movements, like I mentioned, can be really localized. Like a social movement that arises from an Indigenous community might be really localized, or it may be a broader type of movement. And there’s a lot of diversity in the Indigenous movement. So you might have more radical parts, and then you have more kind of liberal, reformist parts as well that also like overlap at times.

Then the anarchist movement is kind of like a separate entity. So I don’t see…I mean when I was first becoming involved in the anarchist movement there was not very much consciousness or awareness for Indigenous peoples struggles, and the concept of anticolonial resistance was very low. And it was Oka, in Canada at least, that contributed to a focus by a lot of movements on Indigenous peoples and their struggles. Because we were inspired by this Oka Crisis.

So through the 90s, I saw a development of an anti-colonial politics among anarchists. Like people in Vancouver, for example, anarchists…there was a kind of decolonization thing that occurred, because previously no one could tell you whose traditional territory Vancouver was built on. And then, throughout the 90s, people became more aware of whose traditional territory it was. And then there was the practice of acknowledging which territory you were on at the opening of a rally or a march or whatever. And then there was the inviting of members of the local Indigenous communities to the events to officially welcome people to them. So I seen that development occur.

Within the anarchist movement — and I think maybe a bit more so in Canada because of the Oka thing, and other Indigenous struggles over the last few decades — I saw more of an effort among anarchists in Canada, and there was a lot of efforts made to engage in solidarity type of work as well. So a highlight might be like Six Nations in 2006 when there were blockaded roadways and just stopping a housing project that was on their territory there. So there was a lot of involvement and a lot of anarchist solidarity work was done with that and a lot of anarchists from Southern Ontario went and participated in some way in the Six Nations resistance.

So I mean, they are kind of different movements, right? Because a lot of Indigenous movements for the most part are coming out of communities and they’re often very family based or a few families in a community. Or maybe half the community or a lot of members of a community are involved in the movement. And so it has a very different dynamic to it. Whereas the anarchist movement is pretty much — I mean you got people who have families who are involved in anarchist movement — but it’s primarily a movement of individuals who come together for collective action and collective work. But it’s not the same kind of dynamic as you have when it’s a community that’s based somewhere for thousands of years, and the family, they’ve all grown up together. And experience of colonialism on Indigenous peoples creates all the different characteristics about it.

There’s things that people can learn from different movements, right? It’s not just the anarchist can learn from Indigenous people, but Indigenous people can learn from the anarchist movement as well. It’s kind of like two different kinds of things, what anarchists should learn from Indigenous movement because the Indigenous movement has a different nature to a different way about it. Just from the history of colonialism, and the experiences of oppression and impoverishment and stuff like that has a big impact.

The movement can conduct themselves in very different ways. But the one thing I see a lot is it’s really hard for nonnatives in general to navigate their way through some communities and their politics. A lot of people fall prey to band councils that have kind of radical rhetoric, but then in the end it’s a kind of stab-you-in-the-back kind of thing. So I think there’s, to some degree there’s some naivety from anarchists about what it’s like in the Indigenous movement.

I think Indigenous people can learn a lot from the anarchist movement, especially the analysis of the Western society, the capitalist state. That’s what I found the most valuable about anarchism was the analytical tools it gave me to understand the state and capitalism, about authoritarian organization and the dangers of that. And the strength of not just diversity but of autonomous, decentralized community. Anyway, I’m rambling, but there’s a lot to learn from each other.

TFSR: No I’m loving it, though. Do you have any more books on the works right now?

GH: No, not right. Right now I’m actually learning more carving, traditional carving. So that’s kind of my main focus right now and that’s what’s taking up a lot of my time and energy as well. So yeah.

TFSR: Oh, great. Is there anything that you want to talk about that I didn’t ask you about?

GH: No, that I can think of.

TFSR: [Laughs] Okay. Thank you very much for this conversation. I really appreciated it. People can find more of your work by searching for warriorpublications.wordpress.com. Is that right?

GH: Yeah, that’s right. Yeah.

TFSR: Cool. Thank you so much Gord.

GH: All right. Thanks for having me.