Shane Burley on “Why We Fight”

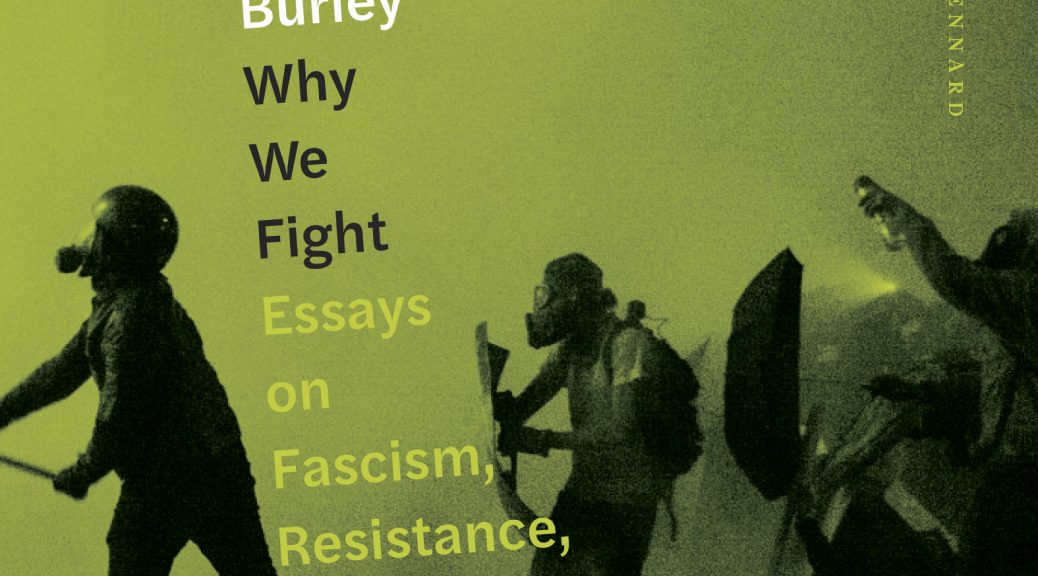

This week, we present a conversation with Shane Burley, author of the new AK Press book, “Why We Fight: Essays on Fascism, Resistance, and Surviving the Apocalypse”. For the hour, we speak about the contents of the book, anti-fascism, toxic masculinity, pushing racists and fascists out of cultural space, antisemitism (including in the left), conspiricism, right wing publishing and other topics.

Bursts references a couple of podcasts at various points:

- Black Autonomy Podcast: Black Anti-Fascism And Armed Self-Defense

- 12 Rules For What #36: Antifascist RPGs and Nerd Cultures w/ Postcards from Cable Street

You can find Shane’s writings at shaneburley.org, support them and get regular articles on patreon.com/shaneburley or find them on twitter at @Shane_Burley1

David Easley Fundraiser

Friend of the pod and prison organizer David Easley could use some support and someone’s collecting money to help him out. You can find more at gf.me/u/zscmgw

. … . ..

Featured tracks:

- Viva Boma by Cos on Funky Chicken: Belgian Grooves from The 70’s

- Andy is a Corporatist by Newtown Neurotics from Kick Out!

. … . ..

Transcription

TFSR: So, I’m happy to be joined by Shane Burley. Shane recently published Why We Fight: Essays on Fascism, Resistance and Surviving the Apocalypse through AK Press. We spoke with Shane in 2018 about Shane’s previous book Fascism Today: What It Is and How to End It. Thank you so much for taking the time to chat, Shane, and for this enjoyable and insightful book. Would you care to introduce yourself further for the audience with any preferred gender pronouns or anything else you want to say?

Shane Burley: Yeah, thanks for having me on, I love the show, I’m happy to be back. I use he/him or they/them pronouns. The new book is a collection of essays, some published before, some were not published before. I write for a number of places, NBC News, Daily Beast, Al Jazeera, Protean magazine. My last book was Fascism Today: What It Is and How to End It from AK Press, and I think, that’s the last time I was on the show, I was talking about that book.

TFSR: I really enjoy that chat and I’m looking forward to this. Can you talk a bit about your focus on the apocalypse in the book? I really enjoyed explorations of End-Time concepts in the introduction and counter-posing a revolutionary hunger for a new beginning versus a reactionary draw for regression back to the purity of oblivion on the Right.

SB: Yeah, it would be dishonest to not discuss this cultural pessimism that we are living in, it’s not even just in the place of the culture, it’s a real depression that we are living in. Socially watching as a collapse basically takes place on a number of different levels: ecologically, economically, socially. As we live through really profound emotional crises, the murdering of BIPOC communities by police, the constant mass shootings… We’re talking now, after a week of basically almost daily mass shootings. We are seeing really massive ecological devastation, one that feels like it’s triggering an accelerated collapse, and it’s really hard to then think about what it means to confront power or improve the world or even great revolution when we’re living in such a state of uncertainty and a real cynicism about the world. So when I look back at the work I’ve done over the Trump years, that was the primary feeling I started to get and also about what it means to live through the apocalypse. So I talk in the book quite a bit about mutual aid work and how people have survived, and how expectations and structures and communities have really changed over time. When we were doing mutual aid work during the pandemic, what stuck out to me a lot more is that people were in need of the mutual aid work more, but also the mutual aid work was better. We had reached a certain capacity on it. Years back, I used to do food not bombs and all kinds of mutual aid work and I felt like in a way it was performative. A soup kitchen down the road did much better than we did. State services were much more effective than we were. We were there for ideological reasons, but people were there to provide services, probably better than we had. That changed, and I think, because of that, that’s opened up a space, a very real space in this crisis – for us. For us to be us, and for us to offer another vision.

So I look in a lot of ways at traditions of the apocalypse that have maybe a different spin on the depressions. I talk about Jewish Messianism a little bit, particularly work of Gershom Scholem and others, with the idea that when we’re talking about the end of the world, the crisis that we’re living through, of collapse, of mass shootings, of the world, that’s actually the day to day realities of capitalism and the state. We can expect that this is basically an accelerated version of the world we live in. It doesn’t end anything. The only way we end it is we change the rules. If the world is actually fundamentally different, then it could actually set the end, and so I pull on this work by Walter Benjamin and others, I’m thinking about what the Messiah means as a concept. And really what the messiah means is that the Messiah brings the end, not the end brings the Messiah, it’s the other way around. And when we think about this in a broader social way, if we’re thinking about this Messianic Age is one that we all participate in the different ways, we pull the pieces together, that it’s actually us that ends the world by building a new one, not just reacting to the crisis as other people have.

And that reminds me in a lot of ways that fascists often present themselves as revolutionaries, but they are a continuation of the same. Being a radical anti-Semite or a radical misogynist is not revolutionary. That’s just a very loud version of the world we live in. What’s truly revolutionary, is to build the world a mutual aid, kindness, and solidarity, that’s a truly radical vision and that’s what actually ends things. So I think when we are going forward, we have to live in the reality of the world that exists now with very serious problems that aren’t necessarily just getting better. We have to start thinking about what it looks like on the other side, and I think that vision of the apocalypse, so to speak, of this profound end and change, is one that we should start to live in, one where we can think about how we’re going to build something new as a form of resistance.

TFSR: Have you read Desert?

SB: I have read Desert, many years ago.

TFSR: It sometimes gets talked about in these terms and for listeners that haven’t, it’s an eco-anarchist text that was published in the early 2000s that talks about what happens if ecological collapse as a process is going on, and how do we take agency during it and make the best out of it possible without… Some people read it as a pessimistic approach to the problem of anthropogenic climate change, but I always took it as this practical approach that. Like “Alright, the government, the militaries are considering this to be a way that the world is going to be shaped differently as we move forward and continuing to shape itself differently. How do we adjust to this? How do we adapt and had we make the most out of it?” So I think, a radical ecological justice-centered approach towards doing a similar thing in recognizing that their power struggles are ongoing seems like an attempt to turn the apocalypse into something else. I don’t know. Maybe gives up too much agency, and I doubt that the authors are wishing for a WaterWorld scenario, but…

SB: Yeah, there is a nihilistic version of that vision of collapse, and it’s actually not just a radical version. We have this all over the place. There’s a giving up or trying to live in the moment, purely in the moment as a way of accepting the reality of climate change, but I think the actual reality is not that someday it will explode in some spectacular moment of excess, but that things just get worse over times and then profoundly change. And I think we’ll be confronted with what does it mean then to build a society. And I think the structures of the past, the states, and economic systems, they will survive to a point through this crisis. But we will have to decide whether or not we’re going to challenge them through that and build something that actually creates a new vision. I think we should obviously deliberately do everything we can to push back an ecological crisis. I don’t want to get anyone an “out” there to say like it doesn’t matter, but we do need to think more about what does it mean to build a world, not just stop that, but in the midst of that, I think by doing that, we’re going to find a much more cogent answer, find a more important answer for how we live our lives, for what effective resistance looks like, but I think we’re also gonna find an answer to the problem itself. We’re gonna find an answer to the ecological crisis by building a world amidst the reality of it and thinking about was the new rules. I saw this meme a year ago, it said “I’ve been trained to survive in a world that no longer exists”. I think we need to start thinking about what world does exist and training each other to survive and flourish by those new rules.

TFSR: Yeah. Your intro also points to the possible limitations of a negative version in movements of opposition, such as like shallow anti-fascism. You mentioned mutual aid as a thing that people have been engaging in and that’s been engaging them more. I want it just like tap up a thing that I heard recently and would love to hear your ideas of it. But in a recent episode of Black Autonomy Federations’ podcast, Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin talks about white anti-fascism as a shallow response that only wants to fight Nazis in the streets without recognizing and actually struggling against the structural fascism faced by BIPOC communities from the start of the American project. What do you see in the anti-fascist movement and vision that gives you hope, and how do you see the building of positive, wider approaches that actually aren’t just oppositional?

SB: I think that critique is really important. Black anti-fascism, in general, has been entirely erased from history. It’s almost as part of a different tradition, a part of this Black radical tradition, that’s not the same as anti-fascism, which I think has a certain narrative to it that anti-fascism is a white radical project or something. And that erases the NAACP NRA chapters that were fighting the Klan, Black Panthers, which was basically an antifascist platform. There are dozens of organizations that go over the history, frankly, a lot earlier than any white anti-fascist organizations which in the US didn’t really come onto people’s radars until the 80s. There are a number of things there. So, on the one hand, it’s a debate over what constitutes fascism. Is the state and police fascism, or only these insurgent white forces? I think that it might actually not matter as much. Both things are important and obviously, intervene into successful life or any equitable just society. I think what people often are focusing on it’s very easy and non-complicated to fight neo-Nazis, that’s not emotionally or morally conflicted in a lot of ways and it’s actually one that can unite ton of people. But when we’re talking about real systemic white supremacy and anti-Blackness, specifically, it becomes really complicated for people and they don’t always jump in with the same ease of commitments. And those movements require a lot more long-term work, we’re talking about really high stakes and talking ones that don’t have easy answers. And so I actually think it sometimes even the push-back from the view of it as anti-fascism is to think about, looking at a situation of what is important here.

So this is April 2021. We have just seen a slew of murders of Black folks by the police. Now when we are looking at the issue, is the top priority the white nationalist organizations, or is it a top priority fighting expansive, violent policing. Well, I think both are and we get to see them actually working together, to have them actually intersecting in really profound ways. We can’t start to see those things as fundamentally separate, and so I would less push back on anti-fascist groups that focus on white nationalists. It’s good to have a focus and be skilled at one thing so that you can do that one thing really well. But I think it’s important for all of us to see how do we work those things together? How do we build coalitions? How do we see larger projects, how are those things able to support one another? And that gets to mutual aid because mutual aid is what is required to have what we used to call social reproduction, for movements to reproduce themselves and exist. We now live in a place where the existing structures of the system no longer can even take care of basic needs in the best-case scenario. So this is what Panthers used to call Survival Pending Revolution programs. It’s what we actually need to survive. And I think what we’re seeing now and what we saw over 2020 particularly, is that any of the mass movements that were rising up to confront the police, one, needed antifascists, because the police were coming with their allies in white nationalist white militias, and (two) they needed mutual aid to just help build the infrastructure, to get people to events, to get people fed at events, to get medical care – all those things that now are required. What we’re seeing now is none of those things can exist independent of one another. If we want to have a vibrant antifascists that pushes back on white nationals, then you have to have a mutual aid structure there to support it. You’re gonna have to have a mutual aid structure to support, if they’re gonna be really mass movements against the police, that has to have their structural base. So now we have to start thinking about what does it mean to build the infrastructure between movements with collaboration and solidarity, and then, more importantly, how does that become permanent? How do we grow and not mean it’s just here for this event, but now we are gonna rely on these structures permanently and they’re gonna grow into a a permanent, existing movement that’s always there. Those are the questions I think we enter into as the world is changing and as we enter a place of permanent struggle.

I was just talking with some reporters about the recent slew of protests around the country this past week, and I was saying, I think the people on the ground no longer have to turn to just one incident. We’re living in a case where there’s constant repression by the police and – communities of color and all around the country – and because of that, we also now have a state of permanent revolutionary action. People are engaging in permanent organizing. This March is all the time, constantly. The generations have changed, people’s realities are changing and now there’s a place of permanent struggle, and because of that, we need the place of permanent collaboration, solidarity, coalitions, and infrastructure.

TFSR: I think it’s pretty fair to say, and from this perspective that an antifascist perspective takes into account the structural dynamics that have been normalized in our society. Obviously, you can say a name like Rodney King, and that sparks a lot of attention for people. There were – besides the individual makeup of that person, his life – there were thousands of Rodney Kings going on simultaneously in the early 90s, in 1992, at the same time, but the wider public’s attention was not captured by the constants of the brutality against Black, Brown and Indigenous populations against poor people more generally, but especially against racialized people. And in my life of around forty years now, I’ve seen an increase of, you know, it’s not just a rebellion every few years. It’s happening as you say, it’s like this perpetuation, this constant thing. Do you think it’s just the technology that’s led to this discussion, the cameras everywhere on people’s phones or the social media activity and people relating to each other outside of the mainstream press or some wider shift in our culture that recognizes the constants of brutality and hears the voices of people that are brutalized?

SB: I think it’s a number of things. I think you are right, technology has a big thing to do, it makes us ever-present. I sympathize with people that are critical of technology, but the reality is that there’s a dialectic to it, that it actually helped, for example, create the visibility around police murders. It helped to create organizing visibility and things like that. It also helps to create repression. Cameras in everyone’s pocket also helps police nab protesters, but it has definitely accelerated that presence. The sense that we’re existing with lots of people all the time… So I checked my Twitter and I can see what’s going on in a lot of people’s lives all the time, and they’re with me all the time. I think that creates that sense of presence and particularly in people’s struggles. So that’s one thing.

We’re seeing certain types of crisis accelerate, environmental and economic ones in particular. So I was born in the 80s and lived through the 90s. There was a lot of sense of perpetual growth when I was growing up, that it just wasn’t going to be a big economic crisis for at least middle-class white communities, but that was a little more of a point of stasis. Well, that has really broken down, that “end of history” mentality has broken down really effectively and also with the increase of just nationalist movements all around the world. I think that we will eventually return to a place of really aggressive, combative struggle. Those things happening in concert with one another creates a bit of that. I think there’s also been generational shifts that happen because of organizing. We actually see the results of a change in consciousness that is a result of real material organizing, the material conditions have affected people’s ideation, the way that, for example, Gen Z thinks about struggle, is a little bit more present than my generation was when I was their age, or, probably the generations before. So there’s been a bit of a move there. I’m not a person who just believes in purely material conditions. I don’t think that when the time is right, the working class just rises up and that happens. I think it actually requires agency for people, but I do think those conditions have dramatically changed. And because of that I actually think people have lived with the notion of organizing a little more frequently, it comes naturally to people a bit more because infrastructure has existed for a while, at least as we transmit histories and things like that. So I think a lot of that’s there. Now that doesn’t mean it’s going to be successful. It means that there’s energy there. It can a lot of directions, so it requires us to intervene, actually channel those things in particular directions, but I do think in a lot of ways, the conditions had just become more dramatic. People’s reactions are more dramatic, the material deprivations are more dramatic and obvious. I think we’re able to see the world a little more clearly now.

TFSR: Stepping forward a little bit and because you’re talking about the material conditions and the changing circumstances that you witness, at least between a sense of perpetual growth versus deprivation, I’d like to jump to the last essay and talk about experiences of broken promises and entitlement and unreachable goals. Your last essay talks about toxic masculinity and not just on the far Right but just as experienced within the wider culture in the so-called United States. And I wonder if you could talk about, including but not necessarily just focusing on incels and Wolves of Vinland, but like the deeper roots in our culture and what you try to draw out in that essay about recognizing the toxic roots of hyper-masculinity or a disembodied masculinity. What was it? Your wife used the term “intoxicating masculinity”. And ways that you see of breaking that cycle of violence.

SB: The essay you are talking about was originally called “Intoxicating Masculinity” and it was the notion we’re talking about, specifically the Wolves of Vinland and the project Operation Werewolf and the way in which it actually makes – I would say a man, but I identify as a gender non-conforming, but a masculine-presenting person, so it has an effect on me and other people of infecting them with this fake euphoric notion of their masculinity, fake promise that people live out with. I was talking with my wife, and we had this joke about, because one of the notions – and here was this tradition – it used to be called masculinism, I’m not sure what it would be called, maybe just would be a part of feminist circles now, but it was talking about “in what way does patriarchy also harm men?” And there is this joke, we’re talking about the Men’s Rights Movement, which I talk a bit about in the chapter, this ultra misogynistic movement. And I was thinking of that meme, where the guy shoots someone and says, “Why did you shoot yourself?” So it’s patriarchy shooting a man looking and saying, “Why did feminism do this?” It’s this idea that patriarchy has created such a profound sense of disconnect in a lot of men, that it creates this constant cycle of toxicity, inability to relate, inability to be whole. And then the question is how do we parse through that in a way. What would even non-toxic masculinity be? Is there something it’s even possible? I don’t know, I don’t have the answer to something like that. But what happens there is that masculinity plays a character in a lot of people’s lives, and a lot of people feel like it’s something that has to be quested after and that the pernicious thing about something like Wolves of Vinland, is that it calls to question on men who were promised something from patriarchy and then are doing everything they can to seek it out and to live it out engaging in the most higher of toxic forms of abuse.

TFSR: Yeah, and also pointing out that Waggener, the founder of it, the self-help industry…: you set someone desiring a path, you set someone seeking this unattainable platonic ideal, and then you just find a way to harvest their energy, while keeping them addicted to the visions of a carrot on a stick in front of them. If you could talk a little bit more about Wolves of Vinland and maybe that character and what they do.

SB: The Wolves of Vinland is a white nationalist pagan group, so basically they were a bit innovative in their structure. They created this group on Nordic paganism, specifically a white nationalist, white supremacist version of Nordic paganism, and they built their organizations like a biker gang. So, you’ll see the guys to get patched in like if they were in one percent or something they were like 1%er…

TFSR: Hells Angels.

SB: Yeah, like those Rebel Motorcycle crews, and they have the hierarchies within that, and they all study the runes. And Paul Waggener had started stepping further in creating these different brands and self-help projects – financial projects and different things. There is one called the Werewolf Elite Program which was making a lot of money and helping people build similar groups to the Wolves of Vinland for themselves. I followed a lot of the program while doing research for about a year and chronicled that. Essentially, what they’re doing is stacking a bunch of very b–rate self-help stuff mixed with intoxicating masculinity, this promise that you could be like Paul, this hulking person, built by steroids and covered in tattoos, and that you would be able to be great and wonderful, just like him. They follow this process, pay him tons of money to basically follow this model and they really ease people into what is an incredibly violent white nationalism by using coded words. By taking people one step at a time, by phrasing things in ways that feel more like a gym or more like maybe black metal culture than it does like white nationalism or what people would assume is white nationalism. And then it takes people along this road and gets people really deeply involved in these projects and sets people up in this revolutionary vision.

So they retell people the story of their own failure as one of something other people have done. You shouldn’t have to be alone. You shouldn’t have to be so poor in your career. You shouldn’t have to live in that house or live in a town where no one respects you. Basically, they offer their program as a solution to that. So, one of the things they talk about absolutely constantly is testosterone. They over-essentialize gender and they use testosterone as a marker for that. What they constantly do in their videos is trying to get people to get on testosterone. What they want they will do is to be injecting testosterone, to have their testosterone as what Paul Waggener says is maximum normal for a human body. That’s what he says is the “correct.” He often uses the term – that’s “correct”. What he is saying there is he’s using testosterone as a proxy for masculinity or maleness. Now, that’s not science, that’s not reality. Injecting more testosterone doesn’t change how you sense. It doesn’t make people’s personalities different, that’s a pseudoscience they’d like the prop up, but what they want to do by saying that is to conflate the two. Your lack of success in your life is your lack of masculinity and your lack of masculinity is bio-social. It involves your testosterone, so by literally injecting testosterone, you’re becoming more masculine as they define it, and so there are all these modules that they have in there to reframe how people think about the world, to put them in the toxic binaries, they think that women or folks of color as fundamentally biologically different than them, and then retail them a story of their own heroism that they can acheive. For example, they are having people constantly working out, but what’s really interesting about their workout programs is that they’re meant to make people intentionally painful and intentionally uncomfortable. And when you do that, you actually break down people’s sense of self. When people are constantly in pain, doing these workouts, they are constantly feeling that they’re improving themselves, that they are participating in something, that they’re part of this great grand story of becoming a hero, and that has an intoxicating effect. It reframes how people think about their lives and think “Oh, wow, I’m on my way to greatness”. In reality, you’re just pumping money into a b-rate self-help program.

TFSR: Possibly leading towards long-term health difficulties from straining yourself perpetually to chase after this goal of looking like Paul.

SB: Yeah, some of the programs in their advice on things like the amount of… I’ve been through all their programs, their not healthy programs, this is not a healthy way of doing things. And this notion that you have to treat your body as an enemy thing sets people up for obvious things like body shaming, but a real, deep sense of discontent with your body, with your own identity. I can’t imagine that anyone in this program comes out feeling anything than worse about themselves and therefore more toxic in their relationships and cling to patriarchy even more so as if it’s going to be the solution to the problem.

TFSR: In an earlier essay called “Contested Space”, you talk about these social spaces that are taken up, particularly in the creation of art and identity, focusing initially on neofolk as activator engaged by the far Right, and in that essay, you also point to what we talked about: the Wolves of Vinland and their connection to a racialized, maybe Assatru Folk Assembly or an Odinist approach towards Northern European neo-paganism. You talk to some of the people involved in, for instance, Heathens United Against Racism. I’m wondering if you could speak a little bit about – in particular, with neofolk or with metal – the taking of the aggressive feelings that people are drawn towards. There’s a history of struggle in spaces of punk and metal, for instance, around racist ideas or anti-racism. If you could talk a little bit about what you found and the expressions of anti-racism from some of the pagan folks.

SB: Yeah, in “Contested Spaces”, we talk about this idea of what are spaces where people from the radical left or working-class communities also might have white nationalists in those same spaces. I think that term was really used for things like Oi, punk rock venues in the 80s, where there be white nationalist bands and also be anarchist bands and there be multiracial bands and they would somehow be in the same “space”, sometimes physically the same space. These were days when venues were not particularly woke to what some of these bands were actually talking about, and so literally people might find themselves in the same space, and so the battle will be held for that space. If you talk a lot of folks in Anti–racist Action or the anti-racist skinhead groups in the 80s – early 90s, a lot of them were going to punk rock spaces specifically and kicking out white nationalists, and they’ll credit that for why we don’t have a ton of white nationalist bands in punk rock these days because they went in and said: “No. This was ours and we’re not gonna cede this ground to you. We are not gonna say ‘Okay, because you’re here, I guess this is yours’”. But that has expanded out to a lot of places where white nationalists and fascists have basically staked their claim in different subcultures. So neofolk music is one, black metal music is one, inside spirituality, Nordic paganism. Honestly, European paganism, in general, has this problem, but particularly with heathenism, which is Nordic Northern European paganism. There are people fighting out there, different fight clubs, different gyms, things like that. People want to have some of those spaces themselves and what it comes down to the fact that fascists don’t belong to these things.

For example, neofolk is a form of music. It uses traditional folk, cultural music, romantic melodies, things like that, mixes in black metal, and other things. That’s music and it attracts people for aesthetic reasons, and I know people who are radical antiracists, anarchists also have some of that. There’s the look to indigenous traditions. There’s the look to the ecological sustainability, things like that. So there’s a reason why traditional folk art might be appealing and so the battle lines of being why does the white nationalist get to have this? Why are they allowed to be here uncontested and to say that this is actually a legitimate form of art for them? They don’t get that, they don’t get anything. So people who are in those subcultures have a unique role in the ability to push those people out, so it’s happening. It’s happening in neofolk with a number of projects, it is happening very heavily in black metal, and I think folks like Kim Kelly and bands like Dawn Ray’d have done a really good job of being divisive in a positive way and saying “Here’s the line: no fascist black metal in these spaces”. In creating intentional spaces for anti-racist, revolutionary black metal.

And groups like Heathens United Against Racism have done that inside Heathen saying like “We’re anti-racist heathens, we have nothing to do with these in these racist heathens. In fact, we are active organizers and we are going to kick them out”. And in a way, they take a special responsibility because they know Heathenism better than non-Heathens, and so the unique angle that they could take it on, and I think the lesson in a lot of ways is a tactical one, it is that people, if you’re in a particular subculture, maybe you’re in a religious group or in something that isn’t explicitly political and that there is far Right influence, it’s on the edges or people trying to make Entryism. You have a unique angle in which you can take it out, and I think a lot of people are taking that in that position that they’re in and using it to push back. I think that’s been incredibly effective. This happens in a lot of different ways that aren’t just about fascism. For example, I’m Jewish, there’s a number of Jewish groups that specifically fight for Palestinian rights because they think “Okay, we have a unique position here in the Jewish community, where we can fight from an angle that maybe other people can’t”. So I think that that’s actually what we’re talking about is what we can do in an anti-fascist sense in these specific subcultures.

TFSR: A thing that I came across recently that another member of the Channel Zero Network that this podcast participates in, 12 Rules For WHAT, which is an anti-fascist podcast based out of the UK, did an interview with this project called “Postcards from Cable Street” about anti-fascist engagements into role-playing games, RPGs, into fantasy and gaming culture that I thought was really a fascinating breakdown, especially asking about okay, so there’s these neo-romantic elements that you find in a lot of fantasy games like orcs and wizards, and whatever else, and those characters or races or whatever often get crudely turned into archetypes by racists that are trying to engage with Tolkien stories or whatever else. That overlaps with a lot of fantasy metal type stuff. I think it’s interesting when people are actively saying “No, actually, and I don’t need to engage with this and take it back. It was never yours, but we’re going to fight you out of these spaces”.

SB: In the original draft of the essay, I had to take it out because it was running long, but I talked about Furries because there is a recent issue, maybe 2019-ish where basically furry conventions were happening, and there was far Right, alt-Right Furry people and folks like Milo Yiannopoulos who were trying to go into the furry world. So Furries got together and decided “No, this is a fascism-free Furry zone” and they engaged as Furry. So they weren’t just an activist group coming from the outside that may not understand or respect Furry culture and saying “Oh, we’re going to take care of this…” “No, we’re taking care of it, we’re gonna organize, we’re gonna learn about this and confront it there.” And I think that’s not the only way, obviously, to approach fascism but it’s a particularly effective one in the sub-cultural world, where fascists actually are. Those sub-cultures are really important for fascist recruitment and organizing. Because they have, for example, a counter-cultural vision and they want to approach people on that counter-cultural level, and they also want to affect what I talk about as meta-politics. Basically the way people think of themselves, the cultural modalities that come before practical politics, and subcultures have a really important role in that. So they want to be in those spaces. Particularly if they see a subculture as the vanguard of coming cultural standards. I think, wherever people are at, they should really – and this is good, in terms of organizing as a journalist, to look at where you’re really at, what communities and networks are you part of, what identities are you working with in this way. Does it give you a unique position in those struggles?

TFSR: Because you mentioned meta-narratives and stories that we tell each other… I thought that the story that you told around the alt-Right publishing houses and far Right publishing houses, for instance, Counter-Currents, are not one that I had seen laid out in such detail before. Can you talk about that project and the world around it? Maybe some other publishing works. Also, Arktos is like a project that I’ve seen in radical bookstores that carry in their fringey sections, like things about conspiracy theories about the Arctic or whatever. And, not for a while at least seemingly, making the connection of some of the other materials that that publishing house carries. I think, if you were to mention some of the far Right thinkers that those houses carry, people might be a bit surprised to see them at their local independent bookstores,

SB: I talk about two publishers – Counter-Currents, ArKtos and those are generally considered two of the biggest, if not the biggest, far-Right publishers in English. What’s interesting about Arktos is I was enjoying a documentary about the Flat Earth Movement a while back and I noticed that when they were at a conference, a big Flat Earth Conference, Arktos was the main sponsor of it. I’m not a defender of Flat Earthers, though I’m guessing most will probably didn’t realize what Arktos was. I think that Arktos and a lot of these publishers basically go where they can. This comes back to the subculture question. They go where they’re not gonna be fought and where they feel like they can build something.

So basically Counter-Currents is an explicitly white nationalist publisher, they publish a lot of books to the right of Richard Spencer. A lot of their authors aren’t people that people would know, but that is not the point. What they do is they create an intellectual canon for white nationalism, where the left or other academic traditions will build big volumes of books, big libraries, they’re gonna do the same thing. Most of the books I came across are just republished blogs and things like that. For example, they have a book that collects blogs that try and take white nationalist lessons from My Little Pony. Real, rigorous intellectual works like that. But what they’re doing is basically making it so that they pile up a number of books so it feels like their tradition has an intellectual weight. What they do is oftentimes publish any author, philosopher, literary figure that was a part of the far Right. So there’s a lot of focus on Ezra Pound, authors that crossed over a bit. Big figures in their movement, Julius Evola, Carl Schmitt, Oswald Spangler. What they wanna do is create that large canon of what they call “traditionalist writing”.

Arktos is also a fascist publisher, though they maybe always don’t lean in with the white nationals quite as much. They are run by a former skinhead and they are pretty openly involved in… They were a part of the alt-Right corporation with Richard Spencer, they created altright dot com and they’ve been a real central piece of the alt-Right movement. They’re known for actually publishing a lot more international stuff, basically translating a lot of fascist philosophers from around Europe, but also folks from South Asia, India, Hindu nationalist authors, a lot of conspiracy stuff, a lot of alt-religion, which is the pieces that often have crossed over. Like you mentioned, it’s not uncommon, at least it wasn’t uncommon to find Julius Evola books in cult or new age bookstores. It wasn’t uncommon to find somebody like, for example, Jason Reza Jorjani who is involved in the traditionalist movement, he ran Arktos at one point, had some questioned relationship with Steve Bannon. He wrote a book basically about how ancient Aryans had ESP and stuff. His book has actually been in para-psychology departments in these book stores. People often allow them in unquestioned.

So those but those books are those publishers have allowed what the alt-Right has also called meta-politics to flourish, to help them build up a really committed base of people by creating a large diffuse set of ideas that they could draw on. A lot of the books you find in Arktos are in contradiction with one another. One couldn’t be true if the other one was true, but that’s not the point. The point is that they want to argue that their far Right position isn’t just simple bigotry, that it is actually deep philosophical tradition with all these different scholars and all these different historical figures, all these different artists that make up a really vibrant living tradition. And that by itself has a propaganda effect. Just the existence of these publishers and these books has a propaganda effect. But when you look even a little bit, you are gonna find that there are actual fascists involved in the organizing of publishing there, a lot of race and IQ kinds of stuff and scientific racism. And basically, anything that they can capture together that they can get from the distant parts the world. They also will sell things that they think are associated with the Left or they think are associated with edgy parts of radical culture. I’ve seen John Zerzan books at ArKtos. Obviously, Derrick Jensen as a favorite over there. They’ve recently published Pentti Linkola, which is a genocidal eco-fascist, but it wasn’t really a part of their tradition before. So what they’re trying to do is get as many things together, so maybe they get someone from this tradition. Maybe they can pull someone from this. They’ve sold neofolk records for a long time. So these are the kinds of ways in which they build up that base.

Counter-Currents specifically has taken a lot of hits since the deplatforming wave that started in 2017 after Charlottesville, mostly because they’re the most upfront about their white nationalism. For example, they publish a tribute to Hitler and things like that. It’s pretty clear, there’s neo-Nazi stuff going on there. Arktos might be a little more confusing for people looking at, though they’ve had a lot of attention because of their attempts to connect with Steve Bannon and with international traditionalist movements and Alexander Dugin, the Eurasianist from Russia. So they’ve had some attention, but I think they haven’t been deplatformed in the way that Counter-Currents has. When the alt-Right first started, it was called alternative Right then, about 2010, around a website called AlternativeRight dot com, that Richard Spencer made. The goal was to build meta-politics. It was the build-up of a philosophical base, with the idea that, if they did that, it could actually help radicalize a group of people that they could move on to engage in movements and that’s what happened. They started in 2010, they didn’t start launching into street activism until 2015, and then with Trump in 2016 they helped ride that wave. Now they’re back in that building phase, and so I think if people want to look at what’s gonna stop the next wave of this specific version of white nationalism, you’d look at Counter-Currents and Arktos because that’s their base, that’s the foundations on which they build their movement.

TFSR: Just to jump back for a second to a range of things that you’ll see coming out of these publishers, fascism has been defined as syncretic before and the ability to hold opposing opinions in this magical sense. So to see something like Savitri Devi standing alongside a New Atheist, Richard Spencer, I guess isn’t that surprising.

SB: Yeah, these things run in complete contradiction to each other. One of the things that Arktos was founded on was this concept of traditionalism which people mostly associate, at least in the US, with Julius Evola. What they wanted to do was to recreate this culture around white nationalist esoterica. In doing so, you’re gonna see a lot of out there stuff that they created symbolic. For example, they publish an old book, a republishing of an old book that says that white people come from an ancient Aryan god race that comes from the Arctic, they descended down through India and was degenerated because of their interactions with not-white peoples. This is a very neo-Nazi myth that was published a hundred years ago, but they’re republishing that now because they believe it literally. That’s not the point. The point is that they like the myths to help build up this cultural sensibility of storytelling about themselves, and that is a lot of the ways in which they think about this, about building a mythology and cultural scene and a sense of identity, it is really foundational for how they approach politics. They’re anti-materialist in a lot of ways, they believe in building a consciousness exclusively and hoping that politics emerges from that consciousness. I don’t think that’s how politics happens. They have been successful in a lot of ways in doing that. So I think people dismiss a lot of their stuff for being so silly, but the reality is that it goes somewhere. They also publish a lot of esoterica that has been involved in real acts of white nationalist violence and terrorism. For example, Julius Evola. Both Arktos and Counter-Currents are really built on republishing Julius Evola stuff that wasn’t in English, and he was really foundational for what was called the Years of Lead. Basically, these fascist terrorists in Italy in the 70s bombing things as a strategy of tension helping them bring down the government. And now, for example, a lot of the Satanist white nationalist writings or stuff to do with Miguel Serrano and different forms of esoteric Hitlerism are inspirational for a lot of Atomwaffen and other groups that are basically engaging in accelerationist violence and plotting attacks on anti-fascist and non-white folks in synagogues, and things like that. So this has a real effect. They build this foundation and it actually results in real acts of killing./

TFSR: Mmmhm. And at least one of the interviews says that their publishing model isn’t so much that the materials are, like people are gonna be buying the books that cost money and keeping them in. It’s more buying the books to put on their shelves, it’s more about the idea of I am identifying with the thing that I am buying and it’s providing funding for this website, but most of the shit that they’re translating, they’re putting out for free online, right?

SB: Most of it is. And actually, the books are really expensive, much more expensive than the books should be. There’s an interesting phenomenon that I’ve only really seen there, which is that they’ll publish a book and publish the hardback and the paperback at the same time. The hardback will be three times as expensive as the paperback. The reason is that you’re buying a prestige copy to give them a large donation. That’s the function of it, you’re not buying literature, you’re buying a token that shows that you have donated to the cause, so to speak, and then the books function in a way of building that sense of allegiance to something. So, for example, there’s a good book I read called The Cleanest Race, it’s about North Korea and racist politics in some of their propaganda. The author describes the way that Juche ideology is created there, where there is these multiple volumes of books and Kim Il-sung basically wrote these to mimic Mao’s creation of a lot of literature. If Mao’s gonna be a great political figure, he was gonna be a great political figure. So he wrote these books. If you’ve ever read any piece of the Juche books, they’re completely incomprehensible, just nonsense strings of words that don’t make any sense, that don’t add up to anything political. But that’s not the point. The point is that they go on someone’s shelf and they are lined up next to each other and they look like a really big canon of political philosophy. Look at all these books, something really deep, a whole nation was built on these books. And that’s what happens here in Counter-Currents.

Some of these books are literally just collections of movie reviews. Greg Johnson’s released, I think, four giant volumes of his movie reviews, some of which were just posted on message boards. This is not important literature that changes lives, but it does add to the canon. Look at all these books, stacks of these books. They must have something really profound to say. And that has been in a lot of ways how the white nationalist movement, particularly in Europe and the US, has helped to create an image that it’s not just street people in boots and braces, but that it’s actually something that has really core ideas because they have a critique that we must engage with. It should go without saying that they don’t have a critique and we shouldn’t engage with it.

TFSR: I guess the last question that I had is: you wrote a chapter “The continuing appeal of anti-Semitism” and I was wondering if you could talk a bit about that. You talk about some of the different historical tendencies in western anti-Semitism, comparing and contrasting the way that they’ve come out between Christian anti-Semitism… I wonder if you could talk a little bit about the blood libel and the trajectory of that into today, cause we see that in relation to QAnon. And there’s also the, obviously, there’s certain Christian sects that have a support for Israel as a state, but that’s based on the idea that if the Israelis get into enough conflict with neighboring states that it’ll bring about the second coming of Christ, which doesn’t seem very much like it’s an appreciation of those people who are gonna get killed in flames from the sky or whatever. You also talk about the space given by the Left to anti-Semitic tendencies, whether it be 9/11 Truthers or some strains of anti-Zionism that bleed into anti-Semitism. So I just threw a lot at you, but I think you wrote really well on the topic.

SB: To start with the blood libels. Blood libel is essentially a medieval Christian concept. There’s this idea that Jews needed Christian children’s blood to make matzoh or to engage in different rituals. I shouldn’t have to say that’s not true, but it’s not true. Basically, this rumor about the Jews led to centuries of expulsions and mass murders, torturing of Jews, and things like that and in a lot of ways set the stage for later conspiracy theories, obviously later Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which is a forgery that allege that Jews were plotting to control the world through deviant modernity and things like that, and lead to a lot of the modern structures of conspiracy theories we have now…

TFSR: And that was produced by the Czarist secret service, basically right?

SB: Yeah, it was under the belief that the coming socialist revolutionaries in Russia were Jews, and so to disrupt the revolutionary work would be to turn people more further against the Jews and also to take their attention off of the Czar. One thing is was really critical about anti-Semitism is that it confuses the direction of power. So, anti-Semitism is fundamentally different than a lot of other bigotries because of the way that it functions. What a lot of it does, it attempts to turn very righteous, for example, class anger against the powerful and turn it back on someone who’s less powerful. So, basically, if you’re angry about rents going through the roof, losing your job, basically saying “Oh, actually, it’s not the capitalist class, not the one percent that controls, it’s this other class of people, these Jews – and maybe you know a Jew in your neighborhood. Maybe the Jew works at the bank or maybe a Jewish person is a landlord, and then we can identify them, single them out and it can redirect anger away from the powerful and back onto somebody else, and so that’s really the function of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. That’s a historical function largely of anti-Semitism, and that’s actually in a lot of ways why there is a continuing appeal towards anti-Semitism, cause what anti-Semitism does, it gives a face and voice to an anger, a class anger and a subjective anger that’s very real and doesn’t always have an easy place to go with. It’s a lot easier to name a name and use demonic images of that person and weird narratives than it is to say “Actually, it’s a system of capitalism and it’s people I can’t get at, they are unreachable a lot of ways, they’re controlling it”. That’s a very unsatisfying narrative. It’s very difficult to organize around that, and anti-Semitism is a stop-gap there. Conspiracy theories are likewise, they’re able to create a more satisfying emotional narrative.

I’m going to oversimplify this, because there are volumes written, but a modern anti-Semitism that shows up in the 18-19th centuries, basically is a secularization of Christian anti-Semitism. Christian anti-Semitism saw Jews as a demonic race that killed Christ, that were working in secret cabals to undermine Christian civilization. They were forced into money-lending in some cases, so then the image became that they were actually responsible for economic problems, even though it’s actually the king and things like that. And when people were looking for a way to explain the changes that were happening in the economy in the world – financialization, contract law, just basically modern infrastructure. The structure was then blamed on the Jews. People looked at old, Christian anti-Semitism that was superstitious and they modernized it with a pseudo-scientific explanation they called anti-Semitism. “Oh, it’s actually the Jews who are creating this new cultural sphere in their own image, they were responsible for Usury, and now the whole world is Usury!” That kind of logic. And that continued through racialization of Jews up into Nazi Germany.

I think one of the things I’m getting at there is why a lot of folks, much of them Moishe Postone, and other Marxists have called structural anti-Semitism is that there are some really basic things in the psychology of Western countries, but now internationally, that mistakes where power is and anti-Semitic narratives make up the underlying superstructure of it. So for example, conspiracy theories are so rampant now and they all come down to a really well-worn track that comes from anti-Semitism. So you mentioned QAnon, it’s the idea that Democrats have a satanic cabal where they use blood for rituals, it is the blood libel, they don’t say Jews quite as frequently, usually, it takes a couple steps on the road to get to Jews, but it literally is the foundation for all this conspiratorial thinking. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion is foundationally how people explain things like Rothschild and George Soros and those sorts of conspiracy theories that have motivated the Right and some parts of the Left as well. What’s happened is that I think anti-Semitism has built up this structural base and it’s really hard to free people of it, because what it does is it manipulates the impulse to liberate oneself. One of the things that I think when you looking at critical theory and people like Adorno and Horkheimer talk a lot about how not all impulses to liberate are actually good. In fact, some of this energy can be turned backward and some fascist moments actually take what Robert Paxton calls “the motivating passions”, basically energy created from class conflict or from the crisis, things like that, and it turns it back on marginalized classes of people. Instead of organizing across the working class or amongst anti-racist coalitions to confront the powerful. So anti-Semitism is a really key piece of that. One of the things I want to get at with this is that not only is anti-Semitism dangerous for Jews and needs to be fought for that reason, but it also is dangerous for everyone, because it takes any impulse to liberate, it destroys its actual ability to do so. We will never liberate people from oppression if we’re wrapped up in conspiracy theories, if we’re looking for Rothschilds rather than looking for capitalism. The continuing appeal of anti-Semitism I talk about is the continuing appeal of easy answers for this to look at the complexity of modernity and try to boil it down to just one or two key elements instead of seeing the complexity and realizing that we have to work together in mass movements to confront it.

There is a certain impulse towards populism on the Left and I don’t have a problem with that in essence, I think that there needs to be a sort of left populism. People have to tell the story in common language and populism, historically, been the language by which working people talk about socialism. “Oh, it’s just working folks, they’re put down by these elite class”. I understand that sympathy, but we can’t stop there. We can’t let that populist anger redirect from who’s actually responsible here, and so I think it’s important to have some analysis in there. It’s important to see things with complexity.

It’s important to listen to Jews when we are talking about anti-Semitism. There’s a lot of mistrust when the claims of anti-Semitism come up that we should be taking seriously. If we want to not go into the direction of conspiracy theories and anti-Semitism, we have to be able to hear people basically creating those boundaries and saying that that’s happening so that we can actually start to work against those trends. That’s really important. I think that we need to obviously be at its best and avoid making grand conclusions and stuff. I thought that the killing of Jeffrey Epstein was suspicious, but I’m not going around saying he didn’t kill himself, because I have no evidence of that and I think it’s really important to be really clear about what we know or we don’t know. And building a common shared reality is I think the foundation where we make effective political decisions. This is true, we need to be really obvious about our bigotries, we are not free of them. We need to be really upfront about the anti-Blackness that we have, the misogyny and a queer-phobia that we have, and that does bleed into our organizing. That’s gonna be really important. But the other answer here, the less satisfying one, is “I don’t always know.” We have never had the revolution, like none other, so we don’t actually know in a way what unites people with the perfect rules of the game. I think there’s a lot of trial and error. We have to be willing to learn, to be subjected with each other and hear that, and we have to be willing to live in a very complicated world that we are now: states, capitalism. Late-stage capitalism operates in ways that we don’t have a clear road map for, and so we’re having to adapt to really complex systems, we need to create narratives to explain those and then to communicate with other people about them. It’s a really challenging project. I think it’s one that we just have to be vigilant in and to really look at the lessons we’ve already learned about the reality, conspiracy theories, bigotries in our organizing and lacks of a path to power.

TFSR: Where did you get the title from?

SB: I got it from Fredy Perlman. The first version of the essay talked a bit about Fredy Perlman, two essays about Fredy Perlman’s “The Continuing Appeal of Nationalism”, which is a good essay. It’s more about left nationalism and the appeal of nation-states as a solution to oppression. I have a somewhat different perspective on that. And though it’s not exactly the same thing here but I think in a way it’s about the appeal of easy answers. The other essay was the “Beirut Pogrom”, which I have mixed feelings about. It’s about the violence perpetrated by Israel, though he gets some facts wrong and things like that, but I went back and forth thinking about both those essays when writing this. I think Fredy Perlman is one of those voices that remains iconic, classic, edgy and useful decades past when it was written. I think it always will be, he wrote so little, but those essays stand out so much.

TFSR: Awesome, I think that’s really well put. Also, it’s Bernie Sanders who killed Epstein.

SB: Hahaha! I heard it was JFK Jr.

TFSR: Tupac.

Okay. I really appreciate you having this chat, for the work that you put out, again, I think I said at the beginning, I think the book was beautifully written. The introduction literally had me tearing up a few times.

SB: I really appreciate it, it’s really kind of you to say.

TFSR: Where can people find your writing, or follow you online? Where can they get the book?

SB: You can get the book anywhere ya buy books and also akpress.org, that’s the publisher. You can find me on Twitter @shane_burley1 and I’ll be putting out a bunch of different articles in a number of places. That should be the prime location.