Stop The Legal Lynching of Ernest Johnson

On February 12th, 1994, Ernest Lee Johnson and his ex-girlfriends’ two sons participated in the botched robbery of Casey’s General Store that took three victims’ lives: Mable Scruggs, Mary Bratcher and Fred Jones. Mr Johnson has no recollection of the murders, was in despair and had been drinking and smoking crack in the hours after his ex-girlfriend broke up with him. A Black man with intellectual disabilities and no former, violent convictions, he was convicted by an ill-informed, all-white jury with the help of Boone County, Missouri, Prosecuting Attorney, Kevin Crane. Ernest Johnson now faces an execution date of October 5th, 2021.

This week, we spoke with Elyse Max, State Director of Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty about the life of Ernest Johnson, the media and court situation he faced, his twice overturned death penalty, the links between the lynching of Black people in the US and the current death penalty, intersections of race and class in who are the victims of capital cases and who sit on death rows, the mishandling of Ernests intellectual disability in the case and other topics.

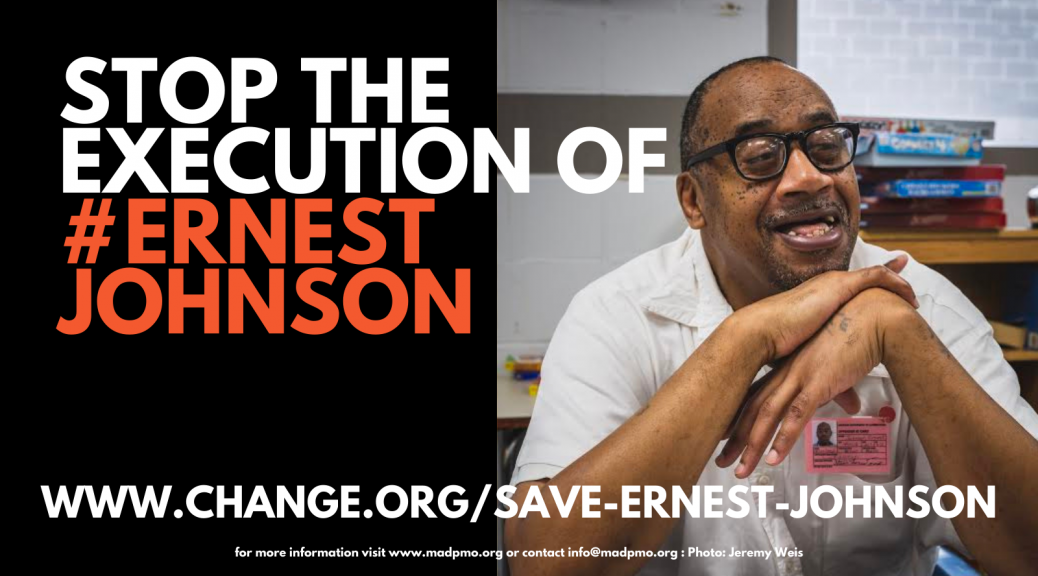

You can learn more about Ernest’s case, including ways to help press Missouri Gov Parson for a commutation of Ernest’s execution and the work of Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty by visiting MADPMO.org. You can follow their work on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram via the handle @MADPMO.

Some other useful links:

- Ernest Johnson petition at Change.org: http://www.change.org/save-ernest-johnson

- The Community Remembrance Project of Missouri: https://www.crp-mo.org

- Death Penalty Info: https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/

- Equal Justice Initiative: https://eji.org/

- “Broken Heart of America” by Walter Johnson: https://www.indiebound.org/book/9780465064267

- Just Mercy documentary: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q7MxXxFu6fI

More info on Swainiac Fest available on Instagram (@Swainiac1969)

. … . ..

Featured Tracks

- For Pete’s Sake (instrumental) by Pete Rock and C.L. Smooth from For Pete’s Sake

- Hangman by Al Dean from The Hangman’s Blues: Prison Songs In Country Music

- Reflections (instrumental) by Diana Ross & The Supremes from Reflections

. … . ..

Transcription

TFSR: Would you please introduce yourself with any name, gender pronouns, location, affiliation, or other information that will help listeners orient?

Elyse Max: Sure. My name is Elyse Max. I am the state director at Missourians For Alternatives To The Death Penalty. We are a statewide organization in Missouri and I work from Kansas City, and my pronouns are “she” series pronouns.

TFSR: We’re here to talk about the case of Ernest Johnson and the Missouri Supreme Court’s execution death warrant dated for October 5 at 6 pm. Would you tell us a little bit about Earnest, about his upbringing, about who he is as a person?

E: Sure. Ernest was born 61 years ago in rural Missouri in Pemiscot County and the city of Steele, Missouri. Ernest was raised in rural Missouri, he went to school in Mississippi County in the city of Charleston, Missouri. Ernest’s family… According to the court documents his father identified his occupation as a share-cropper. And we can see in Earnest’s family history that his maternal and paternal grandparents worked on farms in rural Missouri, which had ties to enslaving people. When Ernest went to school in Mississippi County in the 1960s, it was a segregated school. He never passed the sixth grade, there weren’t services at that time for special education or testing as we know it today. And so Ernest had a rough upbringing, his family history includes many people with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, intellectual disabilities. He had a brother who was institutionalized and passed away. His mother died from what he says is alcoholism. And he didn’t have an easy life. But the folks that know Ernest that grew up with him and that know him now describe him as kind and gentle and soft-spoken. Earnest has no history of violent crimes, and only crimes of poverty, theft, things like that until he was convicted of triple murders in 1995.

TFSR: Do you know much about the context that led up to, as you said, crimes of poverty? What happened that we know of with the robbery at Casey’s General Store in 1994?

E: It was described largely as a botched robbery. We know a lot from media reports and court documents. The crime was committed by Ernest and the kids of his girlfriend at the time. According to reports, his girlfriend had broken up with him that day. And Ernest was in despair, he was drinking and smoking crack at the time. And he went in to rob this Casey’s General Store with his girlfriend’s kids. The three people that were working there were murdered that night: Mary Bratcher, Mabel Scruggs, and Fred Jones. There was evidence that they were bludgeoned by a hammer, some stabs, some shot. To this day, Ernest says that he has no recollection of that night. He was the only one convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death for those crimes that happened in 1994.

TFSR: You mentioned looking at the descriptions in the media at the time. Can you talk a bit about what the trial looked like and what the media landscape looked like for him?

E: Yeah, at the time Boone County, Missouri, it happened in Columbia, which is where the University of Missouri is and it was much different than it is today, it was pretty much a small town. So this crime really shook the foundations of Columbia, Missouri at this time. It was pretty well-covered, with a lot of media attention. It’s stoked a lot of fear in the public. Ernest was prosecuted by Kevin Crane, who was the prosecutor in Boone County at that time, and he is well known in Missouri as a highly problematic prosecutor. He was responsible for the wrongful conviction of Ryan Ferguson, who is now exonerated. In fact, he is now a judge in the state of Missouri. But part of the problem with Ernest’s trial was that his intellectual disability claim has only ever been heard by a jury. In most states, if you have an intellectual disability claim, there is a pre-trial exemption where a judge will settle that before it even goes to court. We believe that’s what should have happened in Earnest’s case. But in Missouri, the law is such that the prosecutor has to agree to the pre-trial hearing for the ID claim. Kevin Crane rejected that, and the judge sided with the prosecutor. So it was just moved directly to a jury trial.

In fact, Earnest’s death sentence, not his conviction, was overturned two times due to errors in the presentation of evidence about the ID claim. In the third trial, he was sentenced to death by an all-white jury that was pulled from Pettis County, and they sentenced him to death for the third time. His intellectual disability claim has never been heard by medical experts, has never been determined by clinicians. And when the Supreme Court made it unconstitutional to execute people with intellectual disabilities, they left it up to the states to determine what those criteria would be. So in Missouri, the criteria match what the APA’s definition is, meaning low IQ, early onset, as well as adaptive deficits in everyday functioning. But because that wasn’t determined by medical experts, the prosecutor relied on racial stereotypes and stereotypes of people with disabilities to win over these juries. The prosecutor, in the third trial, told the all-white jury to rely on their gut, rely on their common sense. And obviously, Earnest had street-smarts. He’s incarcerated, and he can play cards, complicated card games, he can play basketball. Really just urging the jury to rely on nothing that is medical evidence. That’s a huge problem today. So part of our campaign is to push for a board of inquiry that can look at the ID claim from that perspective and make a recommendation to the governor on clemency based on medical and clinical advice.

TFSR: To make it super plain, can you talk about the constitutional basis in which that’s grounded or the moral or ethical basis in which the idea that someone needs to be competent in the US system to face punishment for a crime and actually be held and be considered fully responsible for it?

E: Sure. In 2004, the Supreme Court ruling was Atkins vs Virginia, which made it unconstitutional to execute someone with an intellectual disability. I don’t know the answer to whether or not this is the same as a competency claim, because it isn’t about competency to stand trial, it’s more about being ineligible for the execution. So it’s different than not guilty by insanity because they’re still guilty, but the highest punishment they could receive would be life without parole, so it just makes them ineligible for execution.

TFSR: It’s a strange delineation for me. The way that I’ve always approached was that if someone is considered to be experiencing a different reality than other people, you can’t hold them to all the same standards, as someone who you understand shares the same experience of reality as yourself, or the same ability to cope with the reality and responsibility of what would be a citizen or whatever. And so if the argument that the courts are making by saying, “Look, he can play basketball, he can play complicated card games. Therefore, he understood the ramifications of what he was doing at the time…”

And I’m speaking as if the assumption that somebody deserves to be killed because they’ve hurt other people or killed other people, is the decision that I want the state to make, which is not the case. I don’t think that that decision should be made, which pragmatically is one reason that I think that this conversation is important besides all of the other white supremacist ramifications of this case, in particular. But it seems that in order for someone to get executed for a thing if we assume that that’s the thing that the state should have the right to do, there should be degrees of responsibility taken for an action. And if there is a limit for who can take responsibility for such a heinous crime and receive that sort of punishment, they have to be considered to be operating at the same standards. And it’s reasonable to have the same expectations of participation and understanding and competency that you have of everyone else in the system. Does that make sense?

E: Yeah, that absolutely makes sense. I think that’s very confusing, and it was especially confusing to a jury of laypeople, is that proving that someone has an intellectual disability doesn’t necessarily mean they didn’t know what was going on, or they didn’t understand what was happening. But it means that they didn’t have the same kind of agency that someone that doesn’t have an intellectual disability would have. People with intellectual disabilities are more likely to have coerced confessions, they’re more influenceable. Their agency isn’t the same as someone who would premeditate something and go out and commit a crime. They don’t have that same degree of agency. But it doesn’t necessarily mean that he had no idea, he doesn’t know what he’s going to be executed for, he had no idea what happened on that night. In fact, we recently had a jury sign an affidavit that said that they would reconsider their decision if they had known what the clinical definition of an ID was because the prosecutor was trying to argue that Ernest was coherent, he knew what he was going to do. They said he cased the joint earlier in the day. So it was probably premeditated, but his agency, especially in acting with two other people, was less than someone who didn’t have an intellectual disability. So he shouldn’t be eligible for the ultimate punishment of execution, although he could still be eligible for first-degree murder, which would be life without parole, which arguably is more than sufficient of punishment for anyone. That’s a great question. I think there is a lot of confusion around that, and in no way shape or form should a jury be ever diagnosing or determining what someone’s intellectual disability or what their capacity or their agency is, in that sense, without understanding the medical and the clinical reasoning behind it.

TFSR: I appreciate you responding to that. Thank you. That was muddled “blah, blah, blah, but it doesn’t seem right”.

E: I hope that helps clarify because it isn’t right. And it is hard to understand. It is hard to articulate because it is so almost outlandish.

TFSR: Can you tell us a bit about MADP, Missourians For Alternatives To Death Penalty? How did you get involved in Ernest Johnson’s case? And what’s the current campaign’s goal?

E: MADP, we are the statewide death penalty abolition group in Missouri. We’re the only ones with that single focus. Missouri is not a state that is ready for full repeal. So we do what we call “abolition by attrition”. We just chip away at the system that is so very broken. Things like revising our intellectual disability laws, so that they require a pre-trial exemption for people with ID claims. We are basically just trying to make fewer people eligible for execution. In fact, in Missouri, we have 20 people that are currently sentenced to death. We don’t have a death row, so to speak, they’re integrated into the general population further proving they’re not a future danger to society. We work on the front end and the back end. We follow pending cases, pay attention to prosecutor races in high-use counties, as well as assist legal teams. We follow their lead at the end, like we’re doing with Ernest Johnson when it comes time to bring awareness to the clemency campaign around an execution. We are there, we’re across the board, working throughout the whole spectrum. Before a case even becomes death-qualified, it’s on our radar. And we’re trying to work with legal teams and the folks that have been impacted in order to stop this. And so for Ernest Johnson’s campaign, there are several balls in the air. The biggest issue is the constitutionality of the intellectual disability claim. Our hope, since the Supreme Court of Missouri recently unanimously rejected his habeas petition, our hope is that the governor will grant clemency, grant a stay, to call the board of inquiry to review the ID claim. Our governor and our attorney general have claimed to be champions… For communities of folks with disabilities, they base a lot of their pro-life arguments on the fact that our attorney general has a son with a disability. We really think they’re embedded in that community and that is the issue that could penetrate their hearts and minds and make them look at this in a rational way instead of a political way. And the death penalty is always political.

TFSR: For the audience that maybe didn’t pick it up when you were describing Ernest going to segregated schools in… Missouri is one of the states in the US south but it’s considered to be Midwestern. It’s great plains. But it was under segregation. And you mentioned coming from a sharecropper family. So for folks that don’t know, Ernest would be considered Black under legal standards at a certain point in the United States legal system and has suffered from anti-Blackness, multi-generationally. So can you maybe unpack a little more? You mentioned the makeup of the jury earlier, and there are a few matters in terms of the competency of the jury to make decisions about whether or not he is an individual with developmental delays and disabilities should be held to the standard of the death penalty. But there’s also the wider claim of the constitutional right for someone to face a jury trial by a jury of their peers. Can you talk about the makeup of the jury in Ernest’s case, in any of Ernest cases, and the importance, the underpinning argument of why in southern states where white supremacy is much more near the surface in public discourse than it can be in other parts of the country? Well, that’s unfair. Let me re-state that part because, you know, America, right?.

Can you talk about the importance of that argument and why you’re arguing what he had as a jury during his trial does not hold up to that standard of a jury of peers?

E: Yeah, sure. I think that’s such a great point. The jury is supposed to be the consciousness of the community. In death penalty cases, a jury has to be what is called death-qualified. While they’re selecting jury members, they have to already believe that they can impose a death sentence. So how is that a jury of your peers in the first place? And then to pull an all-white jury from Pettis County, a county which had racial terror lynchings, which had enslaved populations in the past? Those things are our linkages. Really, if we look at the historical acts of racial terror, there are direct linkages between those counties and the modern-day mass incarceration system. And that’s one thing that we do at MADP. Looking at our state work, we look at counties that had high numbers of racial terror lynchings that, had high numbers of enslaved people on the census and overlie them with other indicators, like the Secretary of State’s traffic stop reports – the likelihood that you’re pulled over driving while Black. These historically problematic counties are problematic today. That’s where we see our high number of death penalty cases. Mississippi County just had an extrajudicial murder of a Black man passing through town in their county jail. And that’s where Ernest went to school. There were also four historical racial terror lynchings in Mississippi County, three in Pemiscot County. We work closely with the Equal Justice Initiatives and they connect this history with our modern-day criminal legal system. We know that there’s just such a huge disparity on who is sentenced to die in the United States, and that’s reflected in Missouri. African-Americans nationally make up 40% of people on death row, but only 13% of the population.

But even more so than the defendants’ race, it’s the race of the victim. So in Missouri, if your victim is a white female, you are 14 times more likely to be sentenced to death than if your victim is a Black male. And these are the types of remnants that we see with historical racial terror lynchings that, in the 1940s, they went inside because it became a shame to lynch people publicly. In 1972, the death penalty was abolished in the United States because of the racial bias that was apparent. If you look at the death row in the south, it’s like 75% of people are African-American. So then, when it came back in 1982, they decided that you couldn’t just eliminate the death penalty because of racial bias, but each individual case would be allowed these many rounds of appeals, so they could be sure that they were not imposing racial bias when imposing the death penalty. But as we know, that hasn’t really helped if they’re pulling all-white juries and if we’re having these problematic prosecutors that are remnants of the same thing that happened in the South as is the case was Kevin Crane and the complaints against him. So, Ernest’s case just coalesces all of these broader systemic issues and anti-Blackness within the system, but also connections to our own deep history in Missouri. We were a Union state but allowed to keep our enslaved population, we were just a very divided state. So we often, I think for Missouri, want to appear to be Midwestern. But our economics, our capital is based on racial capitalism. That is still the case today. And that’s so strongly reflected in our criminal legal system, not just statistically but when you look at the way that people of color, especially Black men are treated when they’re going through these trials and these rounds of appeals.

TFSR: I think that the racial capitalism element is a really important thing to contextualize this, too, because there’s, besides huge and visible racial disparities in terms of who is accused of being the assailant in an instance, there’s also an overlap of that with class. And when you look at again, to go back to Ernest’s family history of being sharecroppers, there’s a lineage right there of you are being denied the ability, you’re having your wealth extracted from you, your lives were taken to serve the white supremacist capitalist state, or feudal at that point. And then afterward with the Black codes and with other laws going into the system that, again, Michelle Alexander’s a good example of showing this history and the perpetuity of white supremacist continuation of slavery in the United States. So, generation by generation kept in systemic private poverty, through being forced to go to underfunded segregated schools, through redlining, through all of these economic ventures, people who get the death penalty, almost never are rich people. And when you’ve got the confluence of multigenerational, not poverty, but inability to conserve and hand down wealth that people of color and Black folks and indigenous folks in the United States have facing them. You can’t hire a really expensive lawyer to argue your case for you. You’re stuck going with public defenders, who are systematically deprived of the time and energy to be able to give enough focus to an individual and their case, to actually argue on their behalf and pull the strings and file the paperwork.

E: That is very true and every single person on the currently sentenced to death list in Missouri is with the public defender system. As we watch these new pending cases pop up, that is very evident to us. If you have a private attorney, you’re usually getting your charges dropped to second-degree murder through a plea agreement. And if you have a public defender, oftentimes, there’s not even a plea bargain on the table for you. That is pretty stark. You mentioned Michelle Alexander. If anyone from Missouri is listening, there’s a great book by Walter Johnson called The Broken Heart of America. And it is about the racial capitalism of Missouri, and specifically St. Louis, and how that evolved from Native American genocide all the way to Ferguson and modern-day hyper-militarization of the police in St. Louis. If you like to drill down on that, it’s a really good one to look into.

TFSR: It seems clear with the lines that you’re drawing…. This show identifies as abolitionist as well as anarchist, most of our guests are not necessarily anarchists. My understanding is that your organization is not explicitly an abolitionist organization, but as you said, you could view trying to reverse these and offer support to individuals facing the death penalty in the move towards eventually retracting the death penalty in Missouri as abolition by attrition. Can you just say a few words again about the continuity between lynching and the lack of subjectivity afforded to Black and brown folks in this country historically, and how the death penalty is a continuation of the same struggle, and the struggle against the death penalty is the same struggle towards the abolition of that same un-personhood that we’ve struggled for centuries in this country around?

E: Yeah, sure. The linkage between historical acts of racial terror and the modernity mass incarceration system is well-researched and well-versed, particularly with lynching being manifested within the use of the death penalty and their actual litigation on lynching that happened when it went inside. In the 1940’s, it wasn’t a public spectacle anymore because it actually became embarrassing to gather around it to celebrate these things because of the way public perception was changing in the 40’s. They moved it inside and tried to make it a matter of the judiciary. But there wasn’t the same due process that we have around the death penalty today. So a lot of times it was an accused before the judge, and they went right to lynching. And so the death penalty actually was abolished, Georgia v. Furman, I believe that was in 1972, because of its racial application of it. It came back 10 years later, and the Supreme Court said, “You can’t just abolish it because it’s racially unjust, you have to bring each case and present the individual racial bias in each case.” In fact, last year, North Carolina just granted retrials to every single Black person sentenced to death in North Carolina understanding that there is so much racial bias. Everybody who was sentenced gets a chance to have a retrial where they’re able to present what would have been the racial bias in their case at the time they were sentenced. The connection legally is there. We have this idea that, with the death penalty, there is due process, but the way the death penalty is stacked up, where you have to even be death-qualified to sit on a jury that determines whether someone should receive a death sentence. It’s just…

TFSR: Mind-blowing…

E: It is mind-blowing. I don’t know if I’m trying to find the right word that is appropriate for publication. It’s pretty evident when you trace it back. The museum in Montgomery, Alabama, it’s From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, where Brian Steven works with the Equal Justice Initiative. They collect jars of soil from lynching sites across the United States, they’re on display in the museum. And that’s what we’re working on now in Missouri. There were 60 recognized victims of racial terror lynchings during Reconstruction, and we’re collecting those jars of soil to keep in a statewide exhibit. And through that work, it’s where it really became apparent that historically problematic counties are current problematic counties, where they’re applying the death penalty more often, where there are more traffic stops if you’re driving while Black, where you have higher levels of mass incarceration, extrajudicial killings of Black people. So we need to look at that history and address that history. And that’s part of what our racial justice work is like, I don’t know if we can abolish it until we have come to terms with where these things in our system come from.

So, while our organization isn’t explicitly abolitionists, we’re not trying to abolish the whole criminal legal system, if we take what I believe is the tip of the iceberg, which is giving the state the power to determine who lives and dies through the power to execute, once we can get rid of the very tip of the iceberg, it blows open everything else it. That’s why they won’t abolish the death penalty on racial discrimination grounds is because the Justice has said, “Well, then we’re going to have to look at every single felony, every single life without parole case”. Because the stuff that we’re allowing people to murder by is really the same stuff that is contributing to our whole systemic mass incarceration problem. So I feel strongly as an abolitionist that my work with the death penalty is only going to further the abolitionist cause, even if my organization dissolves formally because we’ve succeeded in our mission of abolition, which would be great. That is only going to blow open this wound that is just going to require more work to be done. We have to be glad and we have to celebrate victories because this work is so hard. Even though I’m not personally a reformist, I know that each step along the way is getting us closer to what we want to see the world around us looking like. I’m very proud of our work and I think that it does contribute greatly to the abolitionist cause overall.

TFSR: Thank you for that. It pretty much started off saying that Ernest Johnson has a standing execution warrant dated for October 5 at 6 pm. That’s very soon. How can listeners help in these coming weeks before that date comes to pass? And it’s not a foregone conclusion that there won’t be a stay, but the very high likelihood and possibility that this man will get executed by the state.

E: Yeah, I think that people inside Missouri and outside Missouri can go to www.madp.org. We have a toolkit that is constantly being updated. For Ernest right now we’re targeting the governor, he’s got the ultimate executive power to grant clemency right now, although I know the legal team is working up to the wire to get litigation going all the way up to the last minute if they can. We’re focusing our efforts on the governor. So there’s information, there’s a call script on our website, a toolkit, some cut-and-paste social media posts you can be making. As we move closer we are going to have a few phone apps and Twitter storms, as well as there’s a petition on change.org that currently has about 18,000 signatures. And we’ll be partnering with the NAACP and several organizations to deliver that personally to the governor on September 29. On our website, we made our homepage The Clemency for Ernest’s page. And also, we have a great comms organizer. So our social media is on fire, I’ve been told. I would just suggest people follow us there and then keep their eye on the toolkit for up-to-date information on how to help.

TFSR: Obviously, there’s a timeliness to Ernest Johnson’s situation, that’s really important. So it makes sense that you have converted the homepage as focused on this case and getting people involved. Are there other ongoing parts of MADP that you want folks to know about and get involved in the longer term? Like, are there ways for people to invest their energy in the organization towards that longer goal of abolishing the death penalty in Missouri?

E: Yeah, thanks for asking that. We have as I said, 20 folks sentenced to death. Unfortunately, 75% of them are in their final rounds of appeals. With the way the United States Supreme Court is and the Supreme Court in Missouri, we need your support, and we need people to get engaged in the issue. Fortunately or unfortunately, the media picks up on innocence cases quite a bit and oftentimes leaves behind the death penalty until it becomes salacious, like the night of the execution, just like they do with the crime, where they want to only focus on the salacious and made for TV parts. And oftentimes, we hear from folks that they didn’t even know we weren’t actively executing state, they didn’t know that we even had the death penalty in Missouri. So we do want people to stay engaged. For the past three years, we have had one execution a year. While that’s less than Texas, we are one of only four states that are currently for 2021 have executions on the books. Just going through the website, we’re a membership organization, you can join for $50 and get our newsletter.

We also are unique in that we have chapters across the state. So it’s great, we have a base that we can activate, we will be activating them on October 5, and as things come on, we’re always using all of our tools – email lists and things like that. And we have several petitions. So we need people engaged all the time. Please don’t be like the media and only focus on it during times of execution. Because these people need support. We have a pen pal program, we hook up folks with spiritual advisors, and all of this is an effort to really just to bring some humanity to people that are in the system, which is what they lack the very most. So lots of ways you can get engaged on very small levels. And also you can make larger commitments as well. Thanks for asking that. I think it’s important that we aren’t only focusing during times of execution.

TFSR: Personally, as someone who entered political organizing around the death penalty, I feel like the movement seemed to hit a national peak in the late 1990s. With media representations like Dead Man Walking and the advocacy and publication of books by sister Helen Prejean, and the popular push to commute the death penalty against former Black Panther, Mumia Abu-Jamal, among other folks. So I guess the timing of that matches up with the 1996 signing by Bill Clinton of the Anti-terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act. I remember that happening at the same time. And that feels like there’s some concordance between those events chronologically.

Where do you see the anti-death penalty movement today, as far as a nationwide movement? And how can people find out more in case they’re not in Missouri and want to get involved where they’re at in this penalty that has no take-backs?

E: That’s a great question. You’re right, it does have no take-backs. I think that there was a peak in the 90s maybe as far as public perception goes, but we saw the tough-on-crime rhetoric. You’re right about the Crime Bill and Clinton, when he was running for president, made a huge public deal about rushing back to Arkansas because he had to oversee an execution. So while I think public perception has changed, that takes a while for that to change in the political sphere. And to the common issue that voters care about, and something that they’re even asking people to care about. I think we’ve come a long way. And really, last year, Virginia became the 24th state to legislatively abolish the death penalty. Actually, they’re the first southern state and they’ve executed over 100 people in Virginia. So it’s very inspiring to see that happen. This isn’t gonna happen through a moratorium. Obama had a moratorium and all it did was set up Trump to execute 13 people at the end of his regime. Biden has a moratorium right now, but he’s still pursuing capital cases, or let me say the Department of Justice is still pursuing capital cases. Eight federal capital cases are happening in Missouri, on top of the 19 state capital cases in Missouri. So a governor-imposed moratorium is a good start, but it’s not enough, this has to come from the United States Supreme Court. We have to determine that it is cruel and unusual. We’re one of the few countries that still continue to keep executions on the books. We’re in the company of China and Saudi Arabia. This has to come through the Supreme Court. I’m inspired by the 24 states abolishing legislatively, because once we can tip the scales and get 26-27-28 states, then we can argue before the Supreme Court again, that it is cruel and unusual and it’s being used rarely and not often, and that it should just be completely abolished.

Part of that is that public perception has to change. They have to run out of people to put on juries. That’s what we’re seeing in Missouri, juries aren’t giving death sentences. So as much as our AG and our prosecutors want to try, the juries aren’t doing it. I think it is moving in that direction, it is a slow haul. The death penalty is as embedded as white supremacy is in America, and they go hand in hand. And so the work that we have to do when acknowledging our past wrongs needs to happen for us to realize what the death penalty actually is and what we are doing by allowing the government to kill in our name. But people that do this work are faced with so many different barriers and challenges in all of the work that we do that I understand why it often gets forgotten.

So it would be nice to have a little sister Helen public revival. Just Mercy came out last year, which is a great movie based on the book by Bryan Stevenson. It’s bringing it back into public opinion. And certainly the slaughter by Trump last year brought it back into the public discourse in such a way that there is now a Federal Death Penalty Abolition Act in the house in the Senate, that’s trying to work through things in that way. It is a long haul, we’re just trying to chip away at it and save every single life that we can, because unfortunately, what we know is that states that abolish have very few people left on the row. Virginia, I think had two people left at the time that they abolished. Missouri has 20 right now, so hoping we can get there but also knowing what that could mean for us is a lot more hard work and sadness ahead.

TFSR: Yeah. A lot of what you talked about in terms of where the decisions get made, we need Supreme Court decisions to say that it’s unconstitutional so the courts can stop applying that. And in order for that to happen, or/and as a stopgap in the meantime, legislative decisions made state by state to say we need to abolish the death penalty, we need to impose a moratorium because they’re less easily retracted than when it’s an executive simply putting something on the books, and then the other party gets in power and they remove it. Then back to organizations like yours that are going out there and applying pressure on the public officials that are supposed to listen to public opinion. What you said about the juries having trouble getting people to sit on them, I think says something about a shift in the public consciousness, I would like to think. That’s not to say positive or negative about people voting or not voting, but it says, if people vote, a lot of people choosing to vote says something about the legitimacy that they feel about the system. And what you’re seeing there is a lack of a voice, which is a statement, even if it’s not clear as to what it’s saying, or the other.

People refusing to participate in trials, because either they just somehow recuse themselves, or more specifically, recuse themselves because they say, “I cannot give a pro-death penalty decision in this case. So you have to kick me off of this jury” says something, says a lot. At the foundation of this and the less visible side of it is public participation in discussions and in organizing with their family and talking to the family about issues like the death penalty. And ideally, that should be what creates the wave that would force to some degree the hand of public officials and courts to actually impose stops on these sort of acts. So that’s why I’m excited to talk to you is because, for people in Missouri, this is a place that they can plug in, this may be more their speed than going out and protesting outside of the jail if they’re an abolitionist, it may be more their speed than doing a number of other things. It’s a way, especially that a lot of people of faith can engage around the issue of life or just people who think that the state shouldn’t have the decision to take someone’s life, that that’s not a choice that the state should be able to have. Sorry, that was repetitious. Are there any national networks that MADP is involved with, or that you know about that do really good works that might have participant groups inside of them that are reflective of specific states?

E: Maybe? I know the Equal Justice Initiative. They have community remembrance projects across the United States and we work closely with many different groups: Amnesty International, the 8th Amendment Project (they don’t have chapters per se), ACOU is a great partner to us. I think that intersection. But making sure – and this is something that we’re working really hard to deal with – is we need to talk about the death penalty as a wrongful conviction. So whenever anyone’s talking about wrongful convictions, they think about innocence and really harsh sentencing. We just need to put the death penalty in all of those discussions. When we talk about progressive prosecutors, they have to be against the death penalty. You can’t be against cash bail and pro-death penalty and, if you’re a prosecutor, that needs to be confronted and I know progressive prosecutors have community coalitions that support them.

So we need to hack the culture, so to speak, so that the death penalty is seen as a wrongful conviction. Murder isn’t ever a public safety measure. So the deterrents argument and all of that is just so obviously untrue when you look at the data and the research. I just want people to start talking about the death penalty and discussing it in the way that we talk about all other wrongful convictions because essentially, that’s what it is. It’s ugly, it’s messy, it’s murder, it’s not fun, and so it gets left behind until it becomes an execution date. I appreciate you bringing attention to it today and understanding it as part of a system and not an anomaly that is just gonna continue to perpetuate these types of injustices.

TFSR: Elyse, thank you so much for participating in this conversation and being available to talk to me and all the great work that you’re doing. I really appreciate it.

E: No problem, nice to talk to you. Thank you so much.