Rojava Again Under Threat of Turkish Invasion

[00:10:35 – 01:45:30]

Emre, Rimac, Xero and Anya, members of the Emergency Committee for Rojava join us on the show this week to talk about the escalation of violence and threats of invasion by Turkey into northeast Syria, updates from the region and their thoughts on how people in the West can help folks living under the Autonomous Administration of North East Syria. You can learn more about their work at DefendRojava.Org and find related interviews covering some of the subject matter discussed and past events on our website by searching for Rojava.

You can keep find Xero’s upcoming podcast, a member of the Channel Zero Network, at ManyWorldsPod.Github.io and you can find the latest of Anya’s co-authored pieces at The Nation (though it’s paywalled).

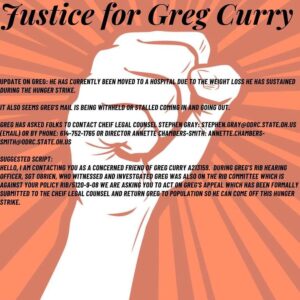

Greg Curry Hunger Strike

[00:01:07 – 00:10:35]

First up, we’ll be sharing a message recorded a week ago by PAPS Texas of incarcerated activist and survivor of the Lucasville Uprising in 1993, Greg Curry, about his hunger strike for the ODRC’s retaliation to his organizing behind bars at Toledo Correctional. Greg’s support is asking folks to contact ODRC officials as he’s entered over a month on hunger strike, had his communication meddled with and has been hospitalized.

First up, we’ll be sharing a message recorded a week ago by PAPS Texas of incarcerated activist and survivor of the Lucasville Uprising in 1993, Greg Curry, about his hunger strike for the ODRC’s retaliation to his organizing behind bars at Toledo Correctional. Greg’s support is asking folks to contact ODRC officials as he’s entered over a month on hunger strike, had his communication meddled with and has been hospitalized.

Greg has asked folks to contact Chief Legal Counsel Stephen Gray by email (stephen.gray@odrc.state.oh.us) or by phone (614-752-1765) or Annette Chambers-Smith via email at annette.chambers-smith@odrc.state.oh.us

Suggested script:

“Hello, I am contacting you as a concerned friend of Greg Curry A213159. During Greg’s RIB hearing, Officer Sgt O’Brien, who witnessed and investigated Greg was also on the RIB committee which is against your policy RIB/5120-9-08. We are asking you to act on Greg’s appeal which has been formally submitted to the Chief Legal Counsel and return Greg to population so he can come off this hunger strike.”

You can find a recent interview with a member of Prison Abolition Prisoner Support on Greg’s case at 1 hour 2 minutes into the episode (mislabeled as September 3rd 2020) at NewDream.US. You can hear our 2016 interview with Greg Curry.

. … . ..

Featured Tracks

-

- Beritan from Jîyan Beats (dedicated to fallen PKK fighter, Gülnaz Karataş aka Beritan, who threw herself from a cliff after a fierce battle in Xakurke rather than surrender to Turkey on October 25, 1992)

- Instant Hit (instrumental) by The Slits from Cut

. … . ..

Transcription

TFSR: So I’m speaking with folks from the emergency committee for Rojava. Would you all care to introduce yourselves with whatever names gender pronouns, where you’re based, and any other info? And any other info about yourself, and it’d be cool to hear about how you became a member of ECR and an advocate for the Rojava revolution.

Anya: I could go first. Hi, everyone, thank you so much for hosting us. My name is Anya, and I’m originally from Ukraine but I have been living in the United States for the last 11 years. And I discovered Rojava and the Kurdish movement around 2017. And I found their project of direct democracy, you know, social ecology, women’s liberation, quite appealing in that they managed to, you know, theoretically, but also in practice to put together all these different struggles on different fronts. So once I discovered it, I started looking for ways to get involved and support the revolution from the United States and have been a member of the Emergency Committee for Rojava almost from its very founding, which was in 2018. And so, you know, the struggle in the United States goes on. Thank you so much again.

Emre: I’ll go next. Hello, everyone. I’m Emre Şahin, I’m a Kurdish scholar from Bakur, Northern Kurdistan. Was based in the US, I’m a PhD student of sociology at Binghamton University. And I’m working on Rojava revolution, particularly woman’s autonomous organizing in Rojava. I did some fieldwork there three years ago, for two months, and I’m excited to be here.

Xero: So I’m Xero I use I use he/they pronouns. I’m based in the US, I’m based in Northwest Pennsylvania, kind of on the southern edge of unseated Erie territory, just south of Lake Erie. I guess what brought me to this revolution was I, you know, kind of have always been, I guess more of a libertarian leftist without really knowing what that meant, or even having a coherent idea of what it involved. I’ve never had much of a patience for reading theory or anything like that. And so when I first learned about the Rojava revolution, it was, god it was in 2020. It was right after the Coronavirus pandemic, and right before the George Floyd uprisings. It was in that kind of a really weird moment where anything kind of felt possible, and this really made a lot of things come into sharp focus for me. It was this example of something that could work at scale. And that was really compelling to me. And so I just didn’t really have much of a choice after that, I kind of went full hog into studying this revolution and kind of similar revolutions around the world. Including the Zapatistas in southeast Mexico, in the state of Chiapas.

And so that, as you’re probably aware Bursts, we’re working on another show that is in conversation with those revolutions, and also talking about land back and other other Indigenous issues here on Turtle Island in a North American context. That show is called Where Many Worlds Fit. And we’re getting very close to being able to start publishing there.

Rimac: Hi, my name is Rimac, I use they/she pronouns. I’m from the Netherlands, I live in a town between Amsterdam and The Hague. And I started supporting the revolution when I started hearing about it in 2015-2016, I was going through a really rough time, personally. I was struggling a lot with my mental health and with taking care of myself, like being able to keep a job and keep an incom because I was struggling with traumas from my youth. I was sexually abused, or sexually attacked, by a close family member as a child and that really kept me in an isolated place where nobody could really stand with me and take care of me. So, I was left really alone. And that’s also when I found out about the women’s revolution, and about the defense against Daesh.

And I also got introduced a little bit to the politics of Mr. Abdullah Öcalan And the revolution gave me so much spirit to persevere through my traumas, and to not give up and to understand that what I experienced was not a single event happening to one person, but a lot of people experience things like this, and that it’s partly because of the patriarchy. So for me, it was really a medicine to learn about a revolution. And then I started looking for people in the Netherlands, for the Kurdish movement, but after the pandemic came and lockdown came it was really hard to maintain contacts. So that’s when ECR came on my path. First, I joined as a member of the study group, which I really enjoyed, because I feel at home at ECR and I feel comfortable sharing my thoughts and learning from others. And then I was also invited to start organizing with them. And I have done this for a year now.

TFSR: Thank you all so much for sharing and it’s really nice to meet you. And as kind of a side note, Emre, I was lucky enough to get to hear an interview that you did with Xero for Where Many Worlds Fit and I’m very excited for the content to start flowing.

E: Oh, great to hear that. I’m excited as well.

TFSR: So, in the January chat with a member of Tekoşîna Anarşîst that we conducted, our guests talked about ongoing rocket and drone attacks across the border into Syria since the Serê Kaniyê invasion of 2019. Could you all, are one of you, please speak about the threat of Turkish invasion looming over the autonomous administration of Northeast Syria, aka Rojava and what’s being expected right now?

E: As an introduction, my comrades and I collectively decided that I would initially begin responding first, and we would follow each other. So I’ll start with some of the questions and others will, hope I won’t be taking too much space.

But in response to the attack, the Turkish threats of invasions have intensified in 2019 but they have actually, we can date them back to the collapse of the peace negotiations between the PKK and the Turkish state near the end of 2015. Between 2009-2010 and 2015, the Turkish state and the PKK had began negotiations to work on the current issue. But that came to an end in 2015 when Tayyip Erdoğan power holding party, AKP, lost the elections in June 2015. And to continue its power it decided to team out with the Nationalist Party in Turkey and ended the peace process. After this Turkey’s relationship with the Autonomous Administration in Rojava became extremely hostile.

There were voice recordings from secret top level Turkish state meetings where the Chief of Intelligence was recorded saying, “Oh, don’t worry, we can start a war with Rojava anytime, we’ll just have a few of our agents throw some rockets over the border to the Turkish side and use that as a excuse.” And from there on the Turkish state began to increase its hostility. Before that Turkey had hosted Saleh Muslim, the former co-president of the Autonomous Administration twice in Ankara for diplomatic talks. This was back when the peace negotiations were still on the table. But after that threat of lost power, and, you know, regional political re-alliances, when the peace process ended the Turkish state initially increased its hostility and then proceeded to invade Afrîn. And soon after Afrîn, invaded Serê Kaniyê in 2019 and it continues its hostile approach to this day.

A: I can add a little bit to that, in particular, what’s happening right now. So Turkish President Erdoğan just announced that Turkey is preparing to launch, and now the invasion, which will be the third invasion, as Emre mentioned the first two. And to basically complete the so called “Safe Zone” that Turkey was negotiating to create with the United States in 2018, before it invaded and occupied more parts of northern Syria. And now, Erdoğan stated that Turkey wants to complete that project and occupy more territory along its southern border with Syria. And at this point, I think we’re quite anxious and, you know, there have been a lot of threats coming from Erdoğan because he and his party AKP, they are using the threats of invasion and actual invasions of different parts of Kurdistan and attacks against Kurdish population within Turkey, but also in Syria and Iraq, as a way to prop up their authoritarian regime and rally support of a broader chunk of Turkish population.

But right now there is this conjuncture of international and domestic factors that makes it quite possible that Turkey, you know, that Erdoğan will actually realize his threats and invade once again. So internationally what’s happening is, of course, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Turkey’s role as a NATO member in stalling the process of NATO accession of Sweden and Finland who just applied to join NATO. Turkey stalls their entry through its demands of lifting a ban on an embargo on arms sales to Turkey and demanding extradition and the crackdown on Kurdish movement and Sweden, and Finland, and termination of any diplomatic relationship that Sweden in particular has with the autonomous administration of Syria. So, you know, Turkey is demanding what’s in its own a geopolitical interest, and it’s quite likely that it will get, at least partially, its demands met.

We have already seen some concessions coming from the United States, the Biden administration has recently requested Congress to approve the sale of F-16, jets and modernization kits for warplanes of Turkey, as well as missile upgrades, you know, various military equipment, despite the existing US sanctions against Turkey, and despite the opposition to it within the Congress. So we are seeing that the United States is granting certain concessions to Turkey and, you know, green lighting another invasion, as the United States did in 2018, you know, could be a likely scenario.

X: I can add a little bit more to that, too, at the risk of making this a little bit more complicated than maybe you were wanting [laughs], because it’s a very messy situation, and there’s a lot of very muddled history here, even in the last 10 years, because the Syrian Civil War is, you know, devastatingly complex. But there’s also two other factors to consider which, one is that there’s the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, the AANES — which is kind of the recognized term for Rojava, this is the administration that kind of runs things. It’s like the decentralized thing that’s based on democratic and federalism. And we’ll get into this later when we talk about the carceral situation as it exists in the region — but one of the things that they have is a set of ISIS prison camps where a lot of former ISIS fighters have been kept. And there’s a there’s a number of danger points there, including recently there have been a lot of mass escapes from these camps. And that’s going to also be a factor when it comes to stability in the region that I’m sure Erdoğan is going to want to exploit somehow.

And then over on the Iraqi side of the border, there’s also a number of things that have been escalating in violence, which is even involving Turkish forces in some sense. Which is that the political situation in Iraq, especially in north Northwestern Iraq, Iraqi Kurdistan, remains a little bit unstable — or not a little bit, that’s putting it mildly — but it remains pretty unstable. And there’s the local ruling Barzani family, which is a Kurdish family that’s much more sort of hyper-capitalistic, and you know, they just have very different political goals.

And there’s been a second route of genocide, genocidal action taken against the Yazidis, and the Yazidis are a local — I personally am not knowledgeable enough to get into whether the Yazidis are Kurds, I’ve heard very firm yeses on that question — but however you classify them, the Yazidis are one of the oldest religious groups in the world and they’re definitely part of this broader Kurdish diaspora. And so they’ve been targeted for genocide by ISIS over the last, you know, 5-10 years. And they’re coming under the threat of genocidal actions, again, by Turkey, and, you know, by these coalition forces in the region. And it’s really devastating to be thinking about things like this, because it’s a very dark situation. But there is some light, you know, kind of buried beneath that, which is that the Yazidis are also taking on Democratic Confederalism, and they’re, they’re realizing their own revolution, which is pretty inspiring.

TFSR: So that was a very complex answer [laughs] it covered a lot of things that I’d like to unpack it in further questions, but very, very informative, and I really appreciate it.

Yeah, and for listeners who maybe don’t recognize the name Yazidi, they may recognize the harrowing situation a number of years ago where ISIS had trapped a number of people in Mount Sinjar, and we’re approaching and genocided them and this is one of the instances where SDF forces were able to come in and help get those folks to safety as as I understand and correct me if I’m wrong, but those were Yazidi minority being attacked by Daesh, specifically.

So, Turkey is the second largest military in NATO, thus a United States ally. And as was pointed to by Anya, there’s ongoing arm sales that are being proposed and engaged right now between the US and Turkey. I wonder if you all could talk about what you understand to be the motivations of the Turkish state under Erdoğan’s AKP and now aligned with the Nationalist Party? What is Neo-Ottoman ism? And can you say some words on transformations of life in Turkey over the last 20 years of AKP rule, and how this relates to the war on Kurdish people within and outside of Turkish borders? Yeah, if you can make mention also of, during this time support for groups like the so called Free Syrian Army, and as well as ISIS or Daesh.

E: Absolutely. Turkey, since the foundation of the Turkish Republic, has had a different sort of political dynamic and diplomatic presence in the globe throughout the 20th century, with the, you know, Republican Party in power for most of the 20th century, with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. It didn’t have this Neo-Ottoman strategy and the Turkish state, for the most part, spent the 20th century trying to modernize the population, modernize the country, so-called “separation of church and state”. And turning its face towards the west, you know, aspiring to be modeling itself after European countries. And this was quite unique in Muslim majority countries, because in Turkey too, majority of the population being conservative, Turkey had had that sort of identity crisis with Western-facing, but Eastern-being [chuckles] population and geography.

However, Erdoğan’s AKP, when it came to power in 2002, adopted a different approach. It’s a populist Islamist party, neoliberal Islamist party, which said, “I’m not going to just face towards the West I’m gonna face towards the East too, I’m gonna reconnect with the East, with the Middle East” you know. But this is only a part of Neo-Ottoman policy. Another part is trying to resurrect the Ottoman Empire’s sort of legacy. Turkey had this trauma of shrinkage, you know, after centuries of ruling over the eastern Europe, Middle East, Northern Africa, after shrinkage to the Turkish Republic. Now with Erdoğan’s AKP in power and cementing stuff further and further into the turkey state, it tried to increase its influence in the Middle East. And many of Turkey’s diplomatic maneuvers over the past 20 years can be read from this lens, you know, from Turkey’s presence in Rojava, in Syria, to actions in Libya and Qatar, there’s this diplomatic shift.

But of course, Erdoğan’s coming into power had political implications and impacts inside the country too. Life has become more and more conservative, public life has been shaped more and mor. The Turkish state has been investing in religious schools, the Directorate of Religious Affairs, which, by the way, even though it’s not a ministry, it’s annual income is higher than the sum of 7-8 different ministries in Turkey. That’s why I said the so called “separation of church and state” even though Turkey is a secular country, the state has tight control over religious affairs. So life has become more and more conservative in Turkey. And these developments at home and abroad, Islamification, went hand in hand of course, as we saw from Turkish involvement in Syria, Turkey has been cozying up to lots of Islamist groups. Like you mentioned, the Free Syrian Army and many factions, which are basically run from offices in Istanbul or have ties in different Turkish cities. Free Syrian Army, you know, their political wing’s representatives residing in Turkey.

However, this is only acknowledged, openly available information. Turkey also had deep connections with extremist Islamist organizations in the past 10-20 years. From al-Qaeda in Syria and Iraq, to ISIS which it later transformed into, Turkey has had close ties. There have been many cases where Turkish journalists have uncovered hundreds of hundreds of trucks of ammunition and guns sent to al-Qaeda affiliates in Syria, by the Turkish state, from Turkey, sent off to Syria. And Turkey still has significant presence in Italy, which is part of a Northwestern Syria, which is not under the control of TFSA, Free Syrian Army actually, it’s under the control of al-Qaeda in Syria, and Turkey works closely with al-Qaeda in Syria.

Also ISIS, there are many reports from the past 5-10 years where ISIS leaders freely reside in Turkey, recruite Turkey, when they’re caught, they’re only caught for show and immediately released. There were reports that even Putin back in 2015 hinted that, when they were not so close with Erdoğan, of oil trade between ISIS and Turkey. And Turkey has maintained close relations with all these Islamist groups from the most, you know, lightweight version such as Free Syrian Army to the most extremist versions such as al-Qaeda and ISIS. And, you know, Turkey’s tried to instrumentalize these Islamic groups in its project to expand, you know restore, Ottoman glory. You know, establish more and more direct influence over the Middle East and North Africa.

Turkey used mercenaries that it recruited from these Islamist factions and sent them to Libya, in its presence and fight in Libya. The same goes for Nagorno Karabakh, as you remember, a year ago, there was a two month war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and Turkey was actively participating in the war on the side of Azerbaijan and hundreds of Islamist recruits were transported from Syria to Azerbaijan via and by Turkey. So Erdoğan has been Islamitising both life at home and, you know, Turkish diplomatic approach to the Middle East, and instrumentalizing these Islamist factions and groups.

Anya: I actually don’t think there’s much to add to Emre’s comprehensive response, I would just want to reiterate that Syria, as Emre mentioned, is a blatant example of Erdoğan’s pursuit of Neo-Ottoman Imperial agenda. Because what they’re doing in Northeastern Syria, you know, Turkey, is not just trying to prevent any existence of an autonomous Kurdish polity, but basically preparing a basis for annexation of those territories that are currently occupied by Turkey and its proxies, described by Emre. Usually referred to as Syrian National Army, because there is a process of ethnic cleansing and demographic engineering going on, there is a process of establishing direct Turkey’s administrative and political control of those territories. And I’m referring to the territories that were occupied in three steps in 2016, in 2018, and 2019, with the last two occupations, those were of the territory that used to be under control of the Autonomous Administration. So, you know, they are basically creating a reality that this part of Syria will become Turkified and Turkey will have, you know, an excuse, a pretext to, perhaps not officially, but basically annex, in practice annex that territory.

TFSR: I was wondering, as a follow up, Anya had mentioned the Turkification, if that’s a word, of the so called “Buffer Zone” area, and the area that is Rojava and that part of the world is Kurdistan, is not just made up of Kurds. It’s made up of lots of different languages, ethnicities, religions, that have lived there for centuries and centuries and centuries alongside with each other under various regimes. But, it’s a very complex and diverse area and my understanding is that the Turkish state is moving out Kurds from that so called “Buffer Zone” between Bakur and that part of Syria in Rojava, so as to create discontiguity between different Kurdish majority populated areas that fallt within the borders of these different nation states. I’m wondering if that’s sort of what you’re pointing to, and also if anyone has any knowledge of how the Syrian state is dealing with the destabilization of its borders by Turkey.

E: Turkey has been forcing Kurds to move out through torture, through, you know, pressure from these parts of Rojava that have been under its occupation over the past 10 years. And this is actually an old policy that the Turkish Republic had used in the 1920s and 30s after the transition from Ottoman Empire to Turkish Republic, in parts of Bakur, that are at the sort of borderlands between Kurdish majority and Turkish majority regions. The Turkish state would force Kurdish populations and bring in Turks from Anatolia, western Turkey. And Bashar al-Assad, current Syrian president’s father in the 60s took from the Turkish playbook and created this Arab Belt policy. Over a decade, Hafez al-Assad, Bashar al-Assad’s father, would force Kurdish communities in today’s Serê Kaniyê, Girê Spî and others parts of Rojava. Kurds were forced to move out, their citizenships stripped, unable to, you know, have their lands, are unable to hold any property, unable to even have official documentation, and forced to move to the Syrian urban centers such as Damascus and Aleppo. Hence, we have Kurdish ghettos in Damascus and Aleppo. And Assad moved Arab families from majority parts of Syria under this Arab Belt project, which was inspired by Turkish Republic policies of the 20s and 30s. So Erdoğan is playing from that playbook, and continuing this demographic engineering. And there’s numerous evidences from Efrîn all the way to Serê Kaniyê of this happening, unfortunately. Which is a direct contrast with the pluralist and harmonious, direct democratic model that’s implemented by the Autonomous Administration in Rojava.

A: I think you also asked about the Syrian government’s attitude, visa vie, Turkeys occupation, and the process of demographic engineering. And I would say that the Syrian government is not an independent, autonomous actor. It has survived all these years of civil war, just because of Russia’s support. So whatever its interests are, it has to balance them off, and ultimately follow Russia’s lead what whatever is in Russia’s geopolitical interest. Whatever Russia is gonna see is profitable for itself in terms of Syrian future. So while in it’s discourse, right, the Syrian government opposed the Turkish invasions and ongoing occupation and its ongoing presence on the Syrian territory, what happened in 2019 was that after Turkey invaded there was a deal made, actually two deals. First, a ceasefire between Turkey and the United States, and then a deal between Russia and Turkey. And according to that deal, Turkey was allowed, by Russia, to basically keep control of whatever territory it had occupied by the time, and that’s the territory that’s currently occupied between Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad.

So basically, at that moment, for Russia, it was convenient to make the deal with Turkey and let it, you know, keep its presence and continue establishing all the political, administrative, economic structures and bringing in families of the Syrian National Army fighters to change the demographic, all the processes. And at the moment, it looks like that Russia may greenlight another invasion by Turkey, again, because of the situation in Ukraine. So, Turkey all this time, has managed to sort of play off both the West, you know the United States, NATO bloc, and the Russian bloc, right? Like Emre mentioned that it’s sort of in between the West and the East in its policies. And same when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine happened Turkey didn’t really support any of these two blocs.

So, it’s sort of managed to carve out a position in between, not breaking off completely from Russia but at the same time it’s, I think people know, supporting Ukraine militarily, you know, by providing drones, right? They have been key in Ukraine’s ability to defend itself. And, you know, at this point, some of the latest statements made by Russia’s high officials sort of indicate another potential deal in which Russia could greenlight another invasion, in return of Turkey’s of certain concessions, visa vie the situation in Ukraine.

E: Thank you for that reminder, Anya, and I’d like to quickly add to the question about the Syrian states responses to Turkish threats and practices of invasion, both during the invasion of Afrîn by Turkey, and during the invasion of Serê Kaniyê, all the official statements coming from the Syrian government were along the lines of, you know, “this is a breech of our national sovereignty, and we will fight for each square meter of our land, etc.” But in Afrîn there was no Syrian Army resistance to the Turkish invasion, because in practice, you know, torn with the civil war, Syrian state did not have any sort of capacity to wage some sort of resistance to Turkish invasion. With the invasion of Serê Kaniyê things began to change because the Autonomous Administration — still unrecognized and fighting for its survival — unable to resist Turkish invasion by itself and unable to garner American support, enough American support. Because Trump basically sold out Rojava in 2019, over the phone conversation with Erdoğan and he ordered his troops to leave and allow the Turkish states to send in his army.

So, Rojava caught in between this situation, unable to garner enough US support, agreed to open up the border areas of Rojava where the northern area was, you know, along the border with Turkey, the majority of those border areas for all the way from Minbic / Serê Kaniyê in the West, to Dirik in the most eastern part of Rojava. Syrian Army troops came back in a smaller presence but still, there wasn’t any resistance or any fight against Turkish invasion, Al-Assad’s strategy is basically this. Al-Assad views Rojava, Autonomous Administration, as traitors who are working with the main enemy, the US, you know, using US support to carve out some sort of autonomy, and unable to finish off Rojava attack and finish off Rojava by itself, unable to do that. Al-Assad has been using this strategy of showing that so that Kurds, or peoples of Rojava, accept some sort of slightly worse result.

So Al-Assad is basically saying, “I will only come and work with you against the Turkish State, if you give up on this project of autonomy, and come back into the control of the Syrian State. So Assad’s strategy has been pretty much this, and this hasn’t been really working, because, you know, the Autonomous Administration and the peoples of Rojava do not want to give up their autonomy and the model of direct democracy and Democratic Confederalism that they’ve been establishing there.

TFSR: So we’ve mentioned both conflicts in northern Syria in terms of actors like the United States, Turkey, Russia, Syrian government, and the Autonomous Administration, and also the conflict in Ukraine has been mentioned. And the US shares membership in NATO, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, with Turkey, so therefore armed allies to each other. Which I mean, for anyone listening right now, unless you’ve already heard some of this before your heads probably going to be spinning about all the different proxy situations that are going on right here…

But so in terms of the amplification of the war between Russia and Ukraine since March of this year — the war that’s been going on since 2014 — there’s been a lot of coverage and we’ve we’ve talked to folks both from Russia, and folks in Ukraine about the experience of the war there and the US has been providing weapons to the Ukrainian government to fend off the invasion from Russia.

So as an anarchist personally, I have to say I condemn the existence of NATO, as I do with all states, but I also support the right of communities to to defend themselves from violence, including from invasions, particularly when they’re attempting to grow a feminist, anti-capitalist, anti-authoritarian and ecological revolution is one season Rojava. I wonder if y’all could talk about these two situations and correlation between them? The use by Ukraine of Turkish drones, for instance in this circumstance, is, you know, just kind of mind boggling, but you know, you do what you can to fend off invasion. But do you feel like the invasion of Ukraine by Russia has kind of overshadowed conflict points in other parts of the world? And how do we do a better job of spreading out and expanding our solidarity into places like Tigray in Ethiopia or other conflict zones that are ongoing?

A: I’ll start off since I’m actually from Ukraine, as I mentioned, so this is a topic close to my heart, even though I haven’t been living there for last 11 years, I still have family in the East in the Donbas region, so I’ve been quite emotional and personally affected by this situation.

But more generally, I just want to point out, and I think it has been quite obvious, that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has once more revealed the hypocrisy and double standards on part of the United States and other international actors, you know, the so called “West”, because we have seen huge outpouring of support, of military support, of discursive support, you know, incredible coverage in the mainstream media for the resistance of Ukrainians, right? I mean, we’ve seen pictures of grandmas with molotov cocktails and all this cheering for that resistance.

However, many people have pointed out that you know, that unconditional support is not usually granted to other instances of armed resistance going on in other parts of the world. I mean, you name it, can we can Palestine or Tigray that you just mentioned, or even the PKK, right, which is sort of an armed insurgency against oppression by the Turkish State kind of justified, right? But the PKK has been on the US terrorist list for more than two decades now, as well as on the terrorist list of other countries. And even though the United States have been supporting the Autonomous Administration of Northeast Syria, it has not, you know, as far as we can see, it’s not planning to take off the PKK off that list, right? While at the same time supporting unconditionally, the resistance of Ukrainians. So you know, this situation is just another example that, you know, when it comes to resistance, it’s only supported when someone’s geopolitical interests are on the line, right? That’s what matters and not resistance itself.

And, you know, another parallel that we can draw is between the invasion of Ukraine as a sovereign state, and then Turkey’s several invasions of Syria, which is a sovereign state. And Turkey’s committing egregious war crimes and human rights violations, which are right now covered in the mainstream media, that are committed by Russia in Ukraine. I don’t think we have seen that much coverage when Turkey invaded Syria, Northeast Syria, repeatedly, right. Again, in terms of kind of material response to the invasion by Turkey, in particular, the last one in 2019, as I already mentioned Turkey was basically allowed to occupy the territory that it invaded. And yes, there was discursive opposition by some parts of the United States government, there were some sanctions implemented in response to that invasion in 2019, but those sanctions were removed almost immediately once the ceasefire was signed and Turkey basically remains in the occupied territories. Again, I mean, I think we see a drastic difference, kind of whose invasions are permitted to take place and who’s opposed?

And just one last thing, I think, you know, the invasion has definitely overshadowed other conflicts, at least during the mainstream media. And I think Turkey has been taking advantage of that. I think later on that we were going to discuss more in detail the military operation that Turkey launched into northern Iraq, which is the Kurdish region of Iraq earlier this year, in April, which recently mentioned, and right now, Turkey is trying to capitalize on the invasion and launch its own invasion, another invasion into northeast Syria. And I’m sure that the Turkish government has taken into consideration the fact that right now kind of the media coverage and sort of the government actions are focused on the situation in Ukraine and may get away with another invasion with less coverage.

X: Anya, that answer was beautiful and I really, really appreciate it. I think that there’s some things that I feel like I can add to that answer. Which is, I think that a lot of what I’m going to have to say, like this entire conversation has been, is going to be really complicated and people’s eyes are probably already glazing over. And so I do apologize for that.

And so I feel a responsibility to start with this, which is that: if you’re somebody in the US, and you’re feeling kind of powerless, the really important thing to remember is that our fates are tied. There is no freedom for us without freedom for them. There’s a number of different ways to express this idea and there’s a number of different ways that it manifests — like we in the Imperial Core and people on the periphery or in the Global South, or whatever euphemism you want to use to describe it — I definitely do mean that we’re in the same struggle together. But I also mean something a little bit more specific than that.

So a lot of hay has been made in the media, and in a lot of so called Western sources about the wheat harvest in Ukraine. Because it is definitely true that Ukraine is the world’s breadbasket, basically, even more so than the American Midwest, which is where I live and we have, you know, wheat crops everywhere. And these global supply chain issues that we’ve already been dealing with during the Coronavirus pandemic, again, are extremely complicated, and there’s a lot of fuckery that’s going on everywhere. But a really, I think, underreported aspect of this, is that Turkey as a polity, as a political entity, the Erdoğan regime in particular, has been fucking with the water supply going down into Rojava. And so before this year even, Rojava was already well under what it needed to be for its wheat supply. A lot of its supplemental wheat supply does come from Ukraine, and there’s a lot of different issues that go along with that, too. You mentioned Ethiopia and the Tigray people, they also are pretty affected by the war in Ukraine and the the kind of serious shortage in the in the wheat harvest. But in Rojava, the way that this, you know, is kind of looking on the ground right now is that they don’t have as much water as they need, they definitely cannot produce all of the crops that they need to produce in order to feed all of the mounds that are there. But things are so bad in the region I think that talking about the Coronavirus pandemic, and the way that that looks on the ground in Rojava, kind of is an afterthought almost, as fucked up as that is.

But one of the things that happens there is because the the AANES, the Autonomous Administration, because they don’t have international recognition, that means that the doses of the vaccine that are meant to go to the people who live there, don’t. They go to the Al-Assad regime, right. And so if you’re looking for something that you can do, and you’re in the US, or you live somewhere in the Imperial Core, one of the things that you can do, as frustrating as it is, is lobby your representatives. As fucking frustrating as that is, believe me I understand, but that is something concrete that you can do is, is contact your representatives, and try to lobby for recognition of the Autonomous Administration as a separate polity. I think that it might be a long shot but it’s definitely something that would help the people there more than any other direct action that you can take from the Imperial Core.

If you want to take a personal step — maybe this is oversharing and maybe you can cut it — but there’s ways to make friends online with people who are in pretty desperate situations. And there’s ways that you can, I don’t want to say leverage, but there’s ways that you can take those personal friendships and make those into a kind of mutual aid. So an example of what this might look, is right now on Onlyfans, there’s a ton of sex workers who are based out of Ukraine or from Ukraine or are fleeing, you know, persecution or, you know, fleeing violent conflict. And the only way that they have to really make money very quickly is to turn to sex work. And so this is an example of an area where there’s a ton of things that overlap with a lot of the struggles that people are familiar with in the US, and it’s even on a platform that’s pretty common and popular in the US. And so if you’re looking for direct ways to directly support people, and you’re not, you know, there’s definitely mutual aid funds and all kinds of other stuff that you can get involved with, but if you’re looking to make friends and kind of have a personal bond of solidarity with somebody, you could do a lot worse than something like that. I think I’m talking a little bit too much. But that’s that’s basically what I wanted to add.

TFSR: So in an interview last year that Duran Kalkan of the Kurdistan Democratic Communities Union, which was conducted by the group Peace in Kurdistan, Mr. Kalkan spoke about his view that while Western governments like the US may strategically partner with the Syrian Democratic Forces under Rojavan control, in the fight against Daesh, or ISIS, they’re not committed to the project of democratic confederalism, but only destabilizing Turkey and opposing Russia and Iranian influence in the region. So as someone who’s based in the US, such as myself, I find this to be a really poignant point of interaction with what’s going on in AANES and within Kurdistan more widely and with the Rojava project. Could you all speak a little bit about the the US relationship with Rojava, the ilegalization of the Kurdish Workers Party or the PKK, as well as the KCK, which I just mentioned, the Kurdistan Democratic Communities Union, and what impact that has on the ground in areas controlled by the Autonomous Administration?

E: The US has had quite contradictory approach towards the PKK and Rojava revolution. Since 1998 the PKK has been on the terrorist list of the US, and the US has actively been supporting Turkey in its war on the PKK. However, when the time came around 2014, around the time of Kobanî resistance, where ISIS had encircle the city, the US’s relationship with the Kurds began to change slightly. And this was mainly due to the fact that the US has plans to fund the Islamist factions and Free Syrian Army, actively supported by Turkey and Saudi Arabia, had backfired. The Free Syrian Army was losing ground to ISIS, the US didn’t see it as an effective partner, but it wanted to continue its presence in Syria, you know, due to several reasons, serious geopolitical position, the proximity to Israel, the US’s closest ally in the Middle East… The US wanted to stay on the ground, but it was finding itself less and less able to do so only through the use of Free Syrian Army. It needed another partner on the ground, and the only option that was available was the Autonomous Administration. And with lots of international outrage, with solidarity from comrades all over the world, public opinion was shifting, you know, people were becoming more and more aware about ISIS atrocities. And, you know, combination of this urgency and the ineffectiveness of the FSA resulted in Obama sending military equipment initially to the Autonomous Administration, and then the US establishing ties with the Autonomous Administration.

I would agree with the analysis and the statement to Duran Kalkan; we have many examples from recent past that support is hypothesis that the US is not committed to the project of democratic confederalism. And it’s only approaching AANES, the Autonomous Administration, as somewhat of a proxy without really supporting it, without acknowledging it fully, without, you know, limiting its support only to military so that it keeps holding that area and ISIS doesn’t come back. We know that Democratic Confederalism is a sort of antithesis of American hegemonic policies and practices. It’s completely reverse of the US states approach, you know, from neoliberalism to questions about women’s rights, and you know, gender equality, to ethnopluralist understandings of life and politics, to decentralized community control over everyday life and decision making in different areas. These are, of course, very threatening for the US, the US has always been hostile to left wing movements. But this has been highlighted during the Cold War era, and even up to this day, its political approach to left wing, any left wing resistance across the world, is destabilizing and destructive.

This has had a tremendous and terrible effect for the peoples of Rojava because of this lack of recognition, this lack of understanding of Rojava’s political, economical, social organization, and only focusing on the military and geopolitics of what’s going on in the region. The support has been shakey and as we saw in 2019, I mean, this invasion of Afrîn was made possible with the green light given by Russia because Russia and the US have this unspoken deal where they have shared areas of influence in Syria. In areas that fall to the west of the Euphrates River, Russia has military control, Russian warplanes roam the skies in the areas to the east of the Euphrates and Syria, most of which, all of which are under the control of Rojava and the Autonomous Administration, the skies are controlled by the US. And because of the dynamic the occupation of Afrîn was made possible with the green light of Russia.

However, the occupation of silicon in 2019 was made possible with the green light of Trump and the US government. And with that invasion alone, 400,000 people were displaced in the region. And that’s close to 10% of the entire Rojava population, Serê Kaniyê and Girê Spî were instrumental in the storage and processing of agricultural products. So there’s been a major hit in that sense to people’s education was disrupted, schools were closed. So this sort of contradictory, shaky approach of the US towards the political project in Rojava manifests in hundreds of lives killed, hundreds of thousands of people being displaced, three or four towns being semi destroyed, and people access to water and food being extremely limited. And it’s been devastating to the region, which is why we need not just military support from all around the world, but also political support and a deeper understanding about the political project that’s going on in the ground.

TFSR: As was mentioned already, I think Xero mentioned it in January, there was massive breakout attempts by members of ISIS, or Daesh, fighters and families from the prison and refugee camps at Hassakeh and al-Hawl, where the SDF had been holding them and international condemnation was broadcast about the conditions there all over the media. I think there was a lot that was lacking from the discussion about the fact that a huge number of those Daesh prisoners, captured after the destruction of the attempted creation of a theocratic state, or caliphate by ISIS, are foreigners whose home countries won’t relocate them. Can you all talk a bit about what happened to Syrians that were held as Daesh, and sort of break open this topic a little bit more about the difficulties of not being recognized as an official state formation and yet being in some ways held to the same humanitarian requirements as state structures that don’t have an interface with you? Like how has international scrutiny caused differences in treatment between people internally displaced by the conflicts in Syria (sometimes you can shorten IDP – internally displaced people) versus those internationals who traveled to Syria to join Daesh?

E: This has been a sore spot. In July of 2019 while I was doing my fieldwork, I attended a three day conference which was held by the Autonomous Administration on this particular issue, on how to deal with ISIS prisoners. Guests from all over the world were present there, along with a couple of people from the US too. And there is this discrepancy. So currently, there is a little over 2,000 former ISIS members imprisoned in the Hassakeh and the whole camps that you mentioned, and a little over 10,000 relatives, you know, family and children of these people, held in these camps. A little over a third of these prisoners are foreigners. Interestingly, Central Asian countries have a much, much more constructive approach and have been repatriating their citizens who went and joined ISIS and were captured by Rojavan forces. For example, Uzbekistan has has taken back more than 300 former ISIS members that are Uzbek nationals. However, many of the Western countries refrain from doing so. And part of part of the reason is that they are working closely with Turkey, but another part of the reason is this instrumentalisation of Rojava’s lack of recognition in the international arena.

However, close to two thirds of the ISIS prisoners and their family members are either Syrian or Iraqi, a majority of the people held in Rojavan ISIS camps are either Syrian and Iraqi. And the Autonomous Administration has different policies when it comes to the nationalities. If the former ISIS member is from a country anything other than Syria and Iraq, they are able to repatriate only if the country is willing to do so and very few Western countries do this. And if the former ISIS member, is Iraqi, the Iraqi government has direct communication channels with the Autonomous Administration of Rojava and takes back, you know, takes back the Iraqi citizens and places them in the camps that they have inside Iraq for former ISIS members.

For the Syrians, the situation is complicated. The majority of the former ISIS people in Rojava camps are of Syrian nationality. And on the one hand, ISIS prisoners are treated differently in the semi carceral system that they have their. You know, all other prisoners are held in general prisons, where if you’re trying to relate it to something that is tied to ISIS, you go to ISIS related courts and prisons that are reserved for ISIS members only. And former ISIS prisoners lose their properties, you know, the only type of people that get their stuff confiscated by the Autonomous Administration are former ISIS members. So there is this sort of harsh approach towards former ISIS members that are from the parts of Syria that have control by the Rojavan Administration.

However, there’s also this attempt to not have this solely carceral approach to crime and punishment. And there is some sort of community arrangement. Over the past 10 years, a few hundred former ISIS linked people have actually been set free but through these processes of alternative justice models — that I know my comrade will go into more detail in a minute. If let’s say you’re from Raqqa, and you were involved with ISIS, somehow, if you and your community can prove that you weren’t a gun wielding member that participated in the killing — you know, many people, when ISIS took over and ruled over a large swath of land for a few years, many people worked with ISIS, but not zealously, you know, driving stuff, because they’re told to or doing nonviolent acts. So, if you can prove that you weren’t violent in ISIS, and if your community, your neighborhood from Raqqa, your relatives and community vouch for you, and [would] go through this alternative justice process, then there is when you would get released. Or, like I said, this depends on, this is a complex matter that depends on sort of the communal vouching and the ability for the Administration to arrange with the community so that this person’s released won’t risk life in the region but will ease the burden on the camps and the maintenance of these camps, because that has been a difficult issue. ISIS, former ISIS members, and their relatives still are trying to resurrect the caliphate inside these camps. One of the main reasons for these breakouts that happened periodically, and they can kill one another when if someone held in these camps is willing to talk to administrative officials, or is willing to somewhat cooperate or show regret, you know, these imprisoned other ISIS people come and kill them. So, it’s very complicated. And my comrades go into more detail.

X: Yeah, thank you, Emre, that was a really good answer. That was pretty comprehensive answer. And I think the only thing that I can add to it is to kind of reframe it a little bit for a US audience who might be used to the way that prisons and the carceral state work here, and just kind of compare and contrast a little bit in order to make it a little bit easier to understand. Because that’s, that’s generally the way I think of it. And so, I think that that might be a good communication strategy. And so the thing I think that is the first thing to say about that, is that the the, the Autonomous Administration isn’t really a state in the conventional sense. And I think that fact alone is low key one of the biggest barriers in in terms of getting international recognition. Because obviously, we have NATO countries and stuff, these are all nation states. And so if you admit somebody who’s not a nation state, it’s kind of a threat to your control over the worldview of the planet. And so this I think is one thing that people, perhaps rightfully, see as kind of threatening.

And so that’s the first thing, is that is that the Autonomous Administration isn’t really run like a state. And so the way that things are enshrined here, where there’s endless bureaucracy, and there’s kind of this cultural attitude that we have laws, and you have to do exactly what it says, by the letter of the law, and you can’t stray a single millimeter outside of that, or else you’ll be put in jail and that’s the right thing to do. The kind of cultural attitudes that you would find in Kurdistan are very different from that. And this isn’t just Kurdish culture, but Kurdish culture is what I know the most about so that’s what I’m going to go into.

There’s a different attitude that comes out of centuries of Kurdish tradition, and Kurdish attitudes about law, which is that if you’re resorting to a law you’re kind of already lost, it’s kind of already too late. And so before they do that, what they prefer to do instead, kind of as a culture, is to look around and just kind of see what are the problems that we’re facing and what can we do about those problems? And so it’s kind of, it’s not prescriptive in that way. It’s much more for example: in Rojava there’s a lot of issues with retribution killings. It’s similar to the mafia, the way that the mafia works but it’s definitely not the same. Where it’s like “someone from my family killed your family and so someone from your family has to do a retribution and kill someone from my family”, and the cycle of violence just will continue. And so the way that they would approach that is to say, “Okay, well, instead of that, how about we just have this neighborhood council of people who live on the same street, or people who live in the same area” and often it’s the grandmas, it’s the neighborhood grandmothers, who would be the first responders to some kind of event, to some kind of, what we would think of as a crime.

If there’s one of these revenge killings, the first person who comes in response to that is a grandma from the neighborhood. And then what happens after that is they wouldn’t consider the crime to be solved when the perpetrator is found and then tried and executed or whatever; they consider the crime to be solved when there’s a truth and reconciliation consensus. Like there’s a truth and reconciliation process, and then that process will reach some kind of conclusion, and the surviving parties will usually agree to some kind of public show of okayness with this. Like there’ll be some kind of neighborhood feast, or there’ll be something. And it doesn’t necessarily make things, okay, between those families but it does make it so that the people who you live around, you’re held accountable to them. If somebody breaks the kind of conditions of this truce, everyone in the neighborhood is going to know who did it and how, and so there’ll be consequences in that way. So it’s much more about social reinforcement than it is about any kind of rigid agent of the state coming after you the hand of God or whatever.

That being said, there are definitely prisons in Rojava. And like Emre was talking about, those prisons are usually reserved for people who are a real, direct safety threat to the people who live in a community. And the name of the game is not really to punish those people, it’s to remove them as a safety threat. So you take them to prison, not to punish them, but because they’re their presence creates some kind of unsafe condition. The goal of taking somebody to prison is much more focused on rehabilitation than it is retribution.

I think there’s a global cap of 10 years that somebody can be in one of these prisons and often it’s much less than that. And so the incarceration rate among the general population is much lower. And in fact, during, I think it was early on in the pandemic — this might have been at the end of 2020, I might need to fact check this — but there was definitely, I’m blanking on the word, but there were people who were released from prison, and they were just forgiven and said, “Okay, you can go home, because we can’t keep you here because there’s an active fucking of plague and that that creates an unsafe condition for you.” “Amnesty” is the word that I was looking for.

Carceration is not the only piece of this, there’s also, for example, there’s the whole women’s revolution and one of the aspects of the women’s revolution in Rojava is that there are women’s communities where anyone, any woman can come with her children or with her immediate relatives or whatever, her friends, what have you, and they can come and they can escape from a battered household situation. And just come and stay and live for however long they need to live there, and learn a skill learn something that can then be used to economically sustain yourself. And that’s also a really important piece of this. And so that’s civil society. That’s kind of how things work in normal circumstances, where you just have a neighborhood and there’s a, for lack of a better word, a crime rate in that neighborhood.

That is very different from the ISIS problem. And so, the reason that very different, and the reason that they don’t resort to laws in order to solve this problem, is because it’s a systemic problem. And it’s the Syrian civil war, and so there’s everything is really complicated and everything is really dark and bleak and depressing. But one of the things that made ISIS possible is that civil wars create these really unstable conditions where you’re not really sure where your security is going to come from. And so if this armed group shows up, and they say “you have to abide by whatever we’re doing, or else” that doesn’t excuse what you then do as a result of that, but it does change the way that you treat the problem. Because many of the people who were, what you might call “Syrian civilians” who came under the control of ISIS, or who was part of ISIS or whatever. A lot of those people weren’t really true believers, they didn’t join ISIS because they wanted to, they joined ISIS because they were forced to under nightmarish circumstances. And again, that doesn’t make it okay. But it does change the way that you treat the problem.

And so there’s a population of people who do stuff that. And then there’s a separate population of people who are generally true believers who come by choice from abroad, and Emre was saying, that accounts for about a third of the of the population in these in these ISIS prison camps in al-Hawl, particularly. And so what you do with these people, the third of the people who are who are coming from abroad, that’s a really thorny problem, because the Autonomous Administration isn’t recognized, and nobody wants to take these people back. And so again, I’m not making excuses for the conditions or anything that, I’m just saying that there’s there’s a context here, and that context is really important.

TFSR: Cool, I found that very helpful. Between the two of you.

As was mentioned earlier, the Barzani governing Kurdish Democratic Party in Iraq has a contentious relationship with the Autonomous Administration and the democratic movement. Turkey has also been leading attacks into Iraq since last year, at least, including allegedly using chemical weapons in the northern regions against what they are calling “PKK militants”. But that hasn’t really been making the news from within the US. Does anyone want to address these activities?

R: I want to share a little bit about my own experience. I don’t know the details about the allegations of the chemical weapons but I was at a demonstration in The Hague in mid-May, where a British delegation, and among them Steve Sweeney, a journalist who has been in the region himself for one year to investigate. He has collected samples of soil, hair and clothes that contain evidence that banned chemical weapons have been used by Turkey. And on May 17, he and others would join the local Kurdish movement to go to the OPCW, the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, to hand over this samples, and to urge for a fact finding team to go to the region to start their own investigations. But very unfortunately, the flight got canceled, so they could not make it to the Netherlands in time, which was very disappointing and frustrating. And then some other people from the demonstration, they took their place. Of course, they didn’t have the samples but they did have the letters and the files, so they went to the building. The police was escorting them and it was so painful to see that they weren’t even let inside the gates. They could not even enter the building into the reception [area] to hand over these documents, but they were just left outside the gate. And I think they handed it over to somebody who would take it inside. And that was so painful to see that it’s not taken seriously, that even with such a big demonstration and action and a call out for supports, that they are just not responding at all.

E: To add on to Rimac’s point, Turkey has been using chemical weapons such as phosphorus bonds and cluster bombs, not only in northern Iraq, not only in partial southern Kurdistan against PKK militants in the Qandil Mountains area, but also in Rojava during its invasion of Serê Kaniyê. Many families were affected by phosphorus bombs that were used by Turkish warplanes. And there was this iconic image of a 6-7 year old boy with all sorts of chemical burns on his body, and samples collected in Rojava, too. And the so-called “international community” that result has been silence in the face of these attacks. And I think this is primarily due to the hostile approach that many countries have towards the Kurdish movement, you know, both in Rojava and in other parts of Kurdistan. Like we said several times today, the recognition of PKK as a terrorist organization, and the criminalization of ALL Kurdish people basically, not just the PKK through this logic, and the PKK is the biggest, is the strongest Kurdish party with the biggest base in Kurdish society. We’re talking about 30-35 million Kurds in Kurdistan, and more than half of Kurds in Kurdistan make up the base of the PKK.

So the West’s contradictory political approach towards the PKK and the Kurdish movement, I believe, is one of the main reasons for this turning a blind eye towards the use of active use of chemical weapons by a NATO member country. And this only serves to illustrate the hypocrisy is about all the Western officials preaching about human rights and sort of democratic measures to be employed in warfare, including the banning of chemical weapons. I guess, as long as you’re a NATO member or a NATO ally and you’re dropping chemical bombs on marginalized, criminalized communities such as the Kurdish movement and the Kurdish people, you get a free pass in chemical warfare.

TFSR: Over the last 10 years of the Rojava revolution, radicals, anarchists and feminists in the US and abroad have attempted to raise awareness about the project in order to grow solidarity, but the only times, at least in the US that I’m aware of, that the topic seems to come up are in the context of emergencies, invasions and war. How have we in the US, in particular, failed at engaging lessons taking inspiration from and building solidarity with the revolution in Rojava? And what has that lost us and our comrades over there and abroad?

R: I would like to answer this question by really zooming in on my own journey, how I became involved, not because my journey is special, but I think that it explains a lot about how difficult it can be to navigate. As I said, in my introduction, that I experienced sexual violence as a child from a family member and I was actually invited by another family member to join them for a vacation in Turkey, in 2015. And I wasn’t aware of the strike of the Kurdish struggle yet, then. And I remember that, at the time, there were some alerts about Turkey that you should not travel too close to the border with Syria, because there was unrest.

And at that time, I only read about Syria in the headlines. I only saw headlines and I didn’t know personally what exactly was going on. But because I was traveling there, I wanted to read up and research what’s going on, what’s happening in this part of the world that I’m very ignorant about. So of course, one of the first things I learned was about the Civil War. And then I learned about the PKK, and about the women’s revolution, about SDF and the YPG fighting against ISIS and also being successful and pushing back against them. But I was I was researching this alone, I was not connected with with organizers or anarchists at that moment yet. So it was very confusing for me to find out who is who and who is fighting for what, in the beginning, I could not even distinguish between like the PKK and the YPG and the Free Syrian Army. I was not aware of it. So I had to research that even further.

And then, as soon as I started leaning more towards understanding that the PKK and the YPG that they were struggling for values that I hold dear as well, I started wondering, but if they are fighting this good fights, for human rights and for liberation and against oppression, and if they are actually like the heroes of this moment in the sense that there are so many parts of the world where the governments and the people are so terrified of ISIS, that they are paralyzed by fear and not doing anything and people on the streets being afraid of each other. And then I thought “if they are so successful in fighting against ISIS, then why are they not celebrated? Why is this not shared?” Especially in the country where I’m from in the Netherlands there’s a really big ISIS scare. And I didn’t understand why there there wouldn’t be more attention to this.

So I came in the struggle of like, “it’s everybody’s word against everybody’s word.” And I stuck with it because I really wanted to find out what was going on. And then I also went at some point to a Kurdish culture event in my area and that’s when I really started to embrace the Kurds and the revolution in Rojava. So, by that time, it was more clear to me who is playing what role, and also that Turkey’s role was not dubious, but just evil. That Turkey is really betraying all the values and out to commit genocide, that they’d have no excuse for their attacks.

But then when I started joining the Kurdish community here in the Netherlands, that was also a bit of a culture shock. Because even though I was aware that we were living in a capitalist society and patriarchal society, and that this was causing a lot of injustice, and unheard voices, even though I was aware of it, and already, like fighting the status quo as much as I could, in my way, it was a culture shock to become accepted by the Kurdish community. Because then I felt that I became a part of the struggle and after revolution. And it’s also because the message of the revolution is what I hold really dear, I think that’s a really important message. And that’s why I am also really glad to participate today in the podcast, because the message is that it’s not only a revolution in Rojava, and in Kurdistan region, it’s not their revolution, it’s from all of us.

Because the way how the PKK decided, at some point, that they are not after their own State anymore but they are instead going after a Stateless world. When I really find out about it, and I started sitting with this, that’s when I felt that this is really also my revolution, and that I have a job to play here in the Netherlands. But it was a big step to start getting to know the Kurdish movement here and understanding what role I can play here. Because I even though I fight against it, I do have a European and a Dutch background, I’m not a Kurdish person. So I have a lot of work to do to change my mindset.

And that is also where, because of the pandemic, we could not organize anymore. And I lost contact with my Kurdish friends. So that’s where I started looking on the internet, to find a community and to find resources and to keep on developing myself, and to really become a student of the revolution to understand what can I do here in the Netherlands. That is how I found out about ECR, I joined a reading session of them. And this is also my message to listeners who feel like they want to do something, but they are looking for ways to get involved and to make an impact: the ECR we have reading sessions, one of the topics we discussed was — and that was over like five or six sessions — we discussed similarities and differences between the Zapatista revolution and the Rojava revolution. And for the 8th of March, the International Women’s Day, we had a session, of course, about women struggle and achievements. And before that, we had really interesting sessions about political economy and the cooperative economy in Rojava.

And these are sessions where we exchange equally, where we get to know each other. And then we also have once a month, the organizing meetings where we try to practice what we are learning, try to inspire each other, we have updates from the region. And for me, it helped a lot to be connected with people who are very aware of what’s going on, because that helps seeing the forest through the trees again. Because if you’re insecure about what is going on, that also makes you insecure to act and to speak out and to take action. So ECR has really helped me to stand stronger, and form my own opinion, and choose a strategy for myself to be a part of the revolution. And so I would like to invite listeners to join us for organizing meetings. You’re welcome to join. However, whatever your background is, or how much you know or don’t know about it, you’re always welcome to join us. You can get an update from the region. We also share news about what’s going on in the United States, revolving Rojava and Kurdistan. We share actions that we are taking to build a broader solidarity, because this is, as I said, it’s not only a Kurdish revolution, it’s not only Rojava, it is a struggle and a resistance at this worldwide. That we are connected in our struggle against capitalism and patriarchy. And then at the end of the meetings, we also have the phone banking, where friends of ours from ECR they always do a really great job of putting together a message of concern. And they have all the phones numbers from relevant people of the government in the United States, and we make the calls and as Xero said it might be a bit boring or even like, doesn’t feel good for people, but it is a really important part, especially as European or American people to really raise the noise in our own countries, and to bring our message because they need to hear our story. And you can find us at DefendRojava.Org. There, you can also sign up to get notifications about events and news.

E: I’ll follow Rimac’s example and begin with explaining how I started to become involved with ECR. Soon after its establishment in 2019, I was already in touch with one of co-founders such as Anya and a couple other comrades. And I’m working on women’s autonomous organizing in Rojava in my dissertation, and particularly in the economic arena, you know, cooperatives, collectives, communes. And, you know, in addition to all the wonderful things we do at ECR, we’ve been doing over the past three years that Rimac mentioned just now, I’ve been involved with Anya and a couple comrades with trying to establish connections and increase solidarity with different cooperatives across the US. We’ve been meeting with representatives from cooperatives in and around New York City, but also from different parts of the US. We’ve been in communication with Equal Exchange, Fair World Project, Colab Cooperative, and USFWC Peer Tech Network, among other cooperatives. We’ve been trying to build connections with cooperatives and collectives in Rojava. As an anarchist, myself, I value this growth of international solidarity among different cooperatives in different parts of the world.

However, you don’t have to be an anarchist, you know, whatever excites you in life, whatever you’ve been working on more, there are options to build solidarity with your comrades in Rojava. I know, for example, if you’re an active feminist, in the US, or in Europe, an organized active feminist and you want to build solidarity that’s also much valued and possible, both through the ECR, which, you know, tries to contribute to this growth of solidarity, but also Kurdish Women’s Movement, which is very well established, internationally, particularly in Europe. And I know, there have been meetings with, you know, different women’s organizing from North and South America. So whatever you’re working on, whatever moves you in life, there is possibility of growing solidarity and connections with corresponding similar organizations and people in Rojava. And the Rojava Revolution’s Democratic Confederalism is an anti-nation-state, internationalist vision that does not only limit itself to the Kurdistan or the Middle East, but for the entire world. So any collaboration, in that sense will be much valued and appreciated.

X: Yeah, I would echo what I heard both of Rimac and Emre say, which I thought they were really beautiful responses. So one of the things that I personally have learned — this is gonna sound really contradictory — one of the things that I personally have learned over the course of my organizing as I get closer and closer to Indigenous movements here on Turtle Island, is the importance of not centering yourself, but also, the utility of centering yourself and when it’s appropriate to and when it’s not appropriate to. Things have to be balanced and I think that’s something that’s really important that I take away from all of this. So I had the good fortune to sit down with a Kurdish journalist Khabat Abbas — who you’ll hear the interview that I did with her, we’ll be dropping an episode after we start dropping episodes — but that was a really wide ranging conversation. And one of the things that I really took away from that was this notion of trying to sit with all of the many, many contradictions in life and not just contradictions of ideas or whatever, but contradictions of feeling and thought.

You know, the way that really intense genocides tend to all also happened at the same time as incredible social movements towards progressive ideas of feminism and liberation and stuff. And the way that you can’t really separate the two. That was a really powerful idea. I think that some cultures might call that, if I’m, again, forgetting the name, non-dualism, I think that Buddhists would have a lot to say about this idea of the yin and the yang, and how good and evil aren’t really opposites. They’re two sides of the same coin and stuff like that. I’ve come around to the idea that these are all things that are too important to carry just one name and we have versions of them in our own culture. And so trying to see these things as a gift, and the gift comes in the form of a seed, and you can choose to plant that seed and you can even tend it like a garden. Because the way that culture works, a lot of the time, is a lot soil. You have to look at the nutrients that are in the soil and you can maintain the soil, and you can change what the nutrients are over time, but it’s not going to happen overnight. It’s going to happen with a lot of work and a lot of really hard, dedicated effort over the course of generations even.

And that’s what the Kurds and other people who live in the region have achieved. Because the Rojava project as a polity didn’t come about because somebody woke up one day and said, “Hey, let’s let’s fundamentally revolutionize everything that we’re doing in civil society”. It came about because these cultures, or these traditions, have been practiced for centuries. And there was a lot of dedicated organizing that happened in the years before the Syrian civil war. The PKK is definitely a factor, the early stage of the YPG, and YPJ, which are the People’s Defense Units, and the Women’s Defense Units, these self defense militias in the region. Those also didn’t come out of nowhere, they were trained with the help of the PKK. And in many instances, they have, you know, overlapping membership.

But these things don’t just happen in a vacuum, they come about because there’s a need for them, even when there’s not a civil war going on. And so I look around at the situation in the context where I live and I see that there’s a dire need for that. And I’m not the first person to notice that, this is not an original observation in any way. But things in the US right now are getting to a dire point where I really worry a lot about, you know, the possibility of genocidal violence in the near future. And the violence that is going to be perpetrated against queer people and trans people over the summer, and how that’s actually about racism, when you boil it down, and how nothing is new under the sun. Everything that happened before will happen again, you know, whatever you want to bring out to say that.

But all of that is to say: that you have these dark things that are happening at the same time as you have incredibly positive things. And the incredibly positive things that I take from Rojava, the things that really stood out to me and the things that I really connected with immediately, were the Women’s Revolution, and the structure of civil society, those are the things that made me realize that I’m an anarchist, I just didn’t put the word to it for a long time. And realizing those things, it was a very non-linear process where I just kind of made all these realizations in my own life and started realizing that I fit into that context, too, and I can be part of those organizing efforts. And that’s a new commitment that I have in my life that I feel more myself than I have in a very long time. Because I’ve was introduced to these ideas.