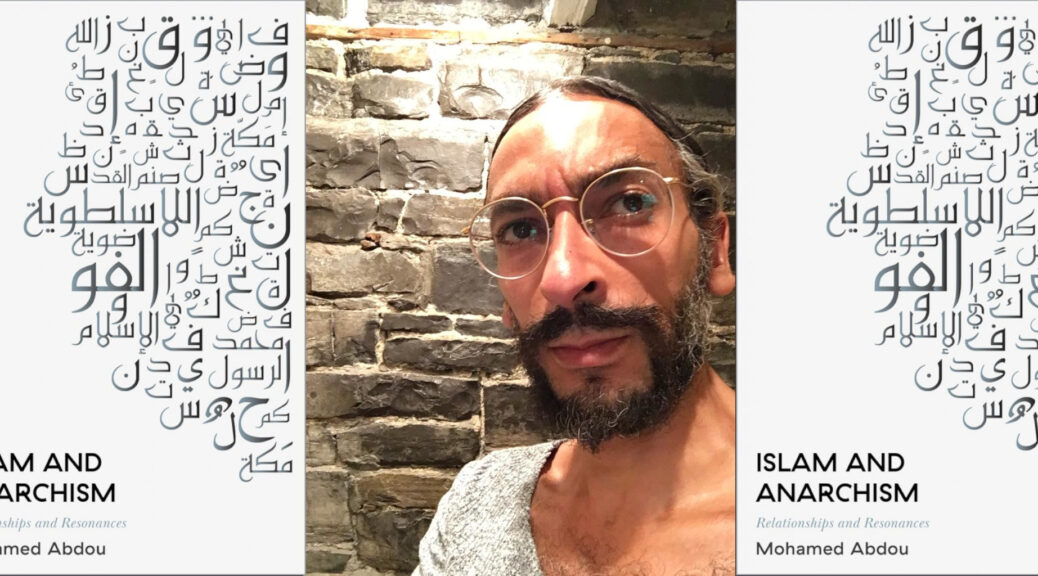

Islam and Anarchism with Mohamed Abdou

This week, Scott spoke with Mohamed Abdou, a North African-Egyptian Muslim anarchist activist-scholar who is currently a Visiting Scholar at Cornell University and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the American University of Cairo. Mohamed is the author of the recent book, Islam and Anarchism: Relationships and Resonances published by Pluto Press in 2022.

For nearly 2 hours, Scott and Mohamed speak about Mohamed’s experience of the Tahrir Square uprising of 2011 and the western media coverage of it, current unrest in Iran, Orientalism, decolonial education, Islam, Settler Colonialism, anarchism and a lot more.

You can follow Mohamed on Twitter at @minuetInGMajor or on facebook at @MohammadAbdou2020

Upcoming

Stay tuned next week for a chat with the organizers of the 2022 Atlanta Radical Bookfair and another surprise topic. For patreon supporters, pretty soon we should be sharing early releases of conversations with Robert Graham about his 2015 book “We Don’t Fear Anarchy, We Invoke It” and with Matthew Lyons on far right christian movements and other chats. More on how to support us at tfsr.wtf/support.

Announcements

And now a few brief announcements

Asheville Survival Program Benefit

For listeners in the Asheville area, you’re invited to an outdoor Movie Night benefit for Asheville Survival Program halloweeny season double feature on Saturday October 8th at 6pm at the Static Age River Spot. There’ll be food, music and merch. To find out more sbout the venue, you can contact Asheville Survival via their email or social media, found at linktr.ee/avlsurvival

Atlanta Radical Bookfair

If you’re in the southeast of Turtle Island, consider visiting so-called Atlanta on Saturday, October 15th where from noon to 6pm you’ll find the Atlanta Radical Bookfair at The Auburn Avenue Research Library on African-American Culture and History in Georgia. There’ll be speakers and many tables, including us!

Hurricane Ian Relief

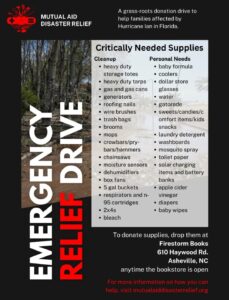

If you want to offer support to folks in Florida around Hurricane Ian, one place to start could be with Central Florida Mutual Aid. They have tons of ways to plug in remotely or on the ground for what is likely to be a long and arduous cleanup and repair effort. You can learn more about them at linktr.ee/CFLMutualAid

Also, Firestorm books is collecting donations of emergency goods at their storefront in Asheville.

Prisons in the Wake of Ian

We’ve regrettably missed the opportunity to promote the phone zap campaigns to raise awareness of prisoners in the path of Hurricane Ian before the storm hit, but suggest that folk check out FightToxicPrisons.Wordpress.Com to learn more about efforts to press public officials to heed the calls to protect prisoners during storms like this rather than follow the path of inertia and cheapness that leads to unnecessary deaths of folks behind bars.

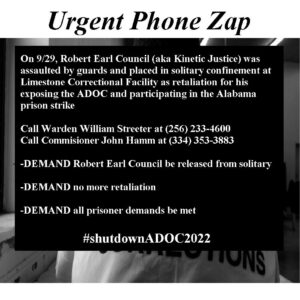

#ShutDownADOC2022

There is currently a prison strike within the Alabama Department of  Corrections known by the hashtag #ShutDown ADOC2022. Campaigners have organized a call-in campaign to demand an end to retaliation against Kinetic Justice (s/n Robert Earl Council) who has been assaulted by guards on September 29th and placed in solitary confinement as well as retaliation of any prisoners participating, Kinetic’s release from solitary and the meeting of prisoners demands. Supporters are asking folks to call Warden William Streeter at (256) 233-4600 or Commissioner John Hamm at (334) 353-3883. You can find a recent interview with Kinetic at Unicorn Riot, as well as more on the prison strike at UnicornRiot.Ninja

Corrections known by the hashtag #ShutDown ADOC2022. Campaigners have organized a call-in campaign to demand an end to retaliation against Kinetic Justice (s/n Robert Earl Council) who has been assaulted by guards on September 29th and placed in solitary confinement as well as retaliation of any prisoners participating, Kinetic’s release from solitary and the meeting of prisoners demands. Supporters are asking folks to call Warden William Streeter at (256) 233-4600 or Commissioner John Hamm at (334) 353-3883. You can find a recent interview with Kinetic at Unicorn Riot, as well as more on the prison strike at UnicornRiot.Ninja

. … . ..

Featured Tracks:

- Blues for Tahrir by Todd Marcus Blues Orchestra from Blues for Tahrir

- Kill Your Masters by The Muslims from Fuck These Fuckin’ Fascists

. … . ..

Transcription

TFSR: So I’m very excited to be talking with Mohamed Abdu, the author of the recent Pluto Press book Islam and Anarchism: Relationships and Resonances, which I think is incredibly important contribution. Yeah. Mohamed, would you introduce yourself with your pronouns and any affiliations or connections that you would like to name?

Mohamed: Wa ʿalaykumu s-salam, Scott. Thank you very much for having me. Wa ʿalaykumu s-salam, for our audience. Insofar as my pronouns he/him or they/them. Insofar as a little bit of background with regards to myself, I’m a postdoctoral fellow at Cornell University, a visiting scholar, an assistant professor of sociology at American University of Cairo, and a self identifying Muslim anarchists and settler of color of North African and Arab descent. I’m a scholar activist. I’ve been involved in movements post-Seattle 1999, the anti globalization movements, as well as Tahrir, with the Zapatistas, indigenous struggles like the Mohawks of Tyendinaga during the struggle over the Culbertson track. And yeah, a lot of movements working towards Palestinian liberation, BIPOC liberation, certainly anti-Statist liberation and anti-capitalist, certainly, but definitely anti-Statist.

TFSR: Great, thank you. I’m so glad to talk with you. Going off of that experience, I thought maybe we could frame our discussion since reading the book, especially towards the end of the book, it seems like a lot of the reflections were spurred on from your experience during the so-called ‘Arab Spring’ and in Tahrir Square. And then, currently, we’re in this moment with the uprising in Iran. I was wondering if you could describe some of the lessons you drew from the momentum that was going on at first, and then how it ultimately failed? And maybe like what lessons still haven’t been learned and how we sort of see the media repeating some of the same narratives?

Mohamed: Thank you. That’s a very important question. Simply because of the reproduction of errors, mistakes, Orientalism. Given the topic of the book, after all, I wrote the book with the sense that language is neither in a certain sense, informational nor communication, as I said in a talk recently. I’m very Deleuzian in the sense that the point of language is something else, its order words, I don’t mean that in an authoritarian sense, but in an action-based sense. Either from one statement to another.

Tahrir, as you can imagine, perhaps the last chapter was quite triggering, it remains very much triggering, simply because there’s a difference between the way that revolutions happen historically and people’s Revolutionary becomings. What happens to people when they rise up emotionally, physically, and mentally? How do they reconcile intimacy? Who’s going to pick up the garbage? What are you going to do with a nuclear power plant? What are you going to do with the army when somebody gets sick? So they involve real practical questions that, I learned offhand, very early on, from the experience with the Zapatistas: there are three things that are necessary for revolution to really be called a revolution or for a revolutionary movement to refer to itself as a revolutionary movement. Number one, you need to have decolonized education, knowledge production, whatever the medium that that manifests within. It could be books, it could be literature, it could be talks, oral histories, and so on, and so forth. Arts zines, and so on, and so forth. A plethora of different forms of knowledge production, because you’re replacing the elements of modern coloniality with a completely different paradigm of reference. In a revolutionary sense, in such a way that people transform in and of themselves.

The Qurʾān, and Muslims know this quite well, as the verse, and they repeat this verse at almost every Friday prayers, Ina – allāha lā yughayyiru mā bi-qawmin hattā yughayyirū mā bi-anfusihim “God does not change your people until they change in and of themselves.” So, it is a matter of the greater jihād, the jihād and the struggle against one’s own inner micro-fascisms, my patriarchy that I have to contend with every single day of my life. I have to learn to listen to women, not just hearing them as in preparing a response or reactionary response to what has just been said, given the asymmetries of power that exists between me and somebody else. And that’s change. Transformation of oneself more-so than “institutions” or the removal of a despot.

Mubarak was not an autocrat, that is to suggest that if Mubarak had complete and utter control and full power. Mubarak depicted himself as God, a pharaoh, indeed he was, but that does not mean (this is the nuance that comes about with words in the Orwellian world that we live in right now in which liberalism both stole the words and their meanings)… There is no such thing as an autocrat because we always have agency. Egyptian participated in the facade. Within Tahrir, before Tahrir, and following Tahrir: sexual harassment, anti-blackness, nepotism, rishwa, all kinds of factors, of dimensions. There was no alternative project that the so called masses have… We have to understand that these masses were wide they were diverse: you had the hijabi, and you had the chain smoking, the nekabi woman, you had the liberal woman, you had anarchists certainly, the Marxist Leninist Revolutionary Socialists referred to as Al-Ishtrakiyin Althawriyeen. You had, of course, the Muslim Brotherhood, you have other forms of Islamist, insofar as Salafi’s, and so on and so forth. You have the Nasserites, you have the Sadatists, so of course, you had the liberals, and so on and so forth.

There were no discussions amongst these different factions with regards to what tomorrow was going to bring insofar as how we were going to bring about the pluriverse world, or if we were remotely interested in that. There were no discussions of the ethics of disagreements, insofar as what bound the millions of folks that were in Tahrir together, let alone what distinguished them as parts. People were merely engaged, and this is part of, unfortunately, the inferiority complex, the cycle effect of Fanonian violence that we internalized in reactionary ways. Now granted, we were in the heat of the battle, and when you’re fighting police forces, the army, we burnt 99 police stations, so… so much for nonviolent revolution. And of course we have sent a letter, comrades of Cairo, actually, had written a letter to Occupy Wall Street insofar as the facade of non-violence, because it’s quite desecrating and insulting that over 1000 people die, are martyrs, that we have yet to honor because we have yet to fulfill their dreams or see through their dreams, and assume that this was a nonviolent revolution. Of course it was not a Twitter revolution as it’s Orientally depicted within Euro-American media, conservative/liberal, and so on, so forth, either. We had to go, knock door to door because the internet was cut out. We had to establish our own community councils, women were ‘manning’ checkpoints, so we see a breakdown of gender relations. Queer folks engaged in a Pride March, and so on and so forth.

So, the potential was there, insofar as social transformation and change. For the first time in Egypt’s history, youth were bringing in cleaning materials from their households, and literally getting on their hands and knees and scrubbing Tahrir. There was a sense of ownership of space, or a sense of belonging to space, a ruptured space and time galvanized the world. But unfortunately, there were a lot of projections that fed into the middle to upper class English speaking so-called revolutionaries, that really most of which had no experience insofar as grassroots organizing, or the intellectual base from which to think through, “what are we going to do tomorrow?” [For instance,] Egypt is complicit in the occupation of Ghaza, the largest concentration camp in the world by air, land and sea. All these geopolitical factors, these local factors, these regional factors, the assumption that we would just be allowed to do whatever it is that we wanted to do was obviously an illusion.

In so many ways, I lost my voice speaking in Tahrir. Shiearat, or slogans, as was occurring in Iran, of Freedom (huriyya), Bread (aīsh), Social justice (al-adāla igtimā‘iyya). What kind of social justice are we talking about here? How do you bring it about? What kind of freedom? What kind of rights? Because you were asked to people and you won’t get the same response. Well, so what exactly are we talking about here? Where is the strategic revolutionary plan? Now that we can’t plan uprisings as much as we can prepare for them. The Zapatistas have a saying, “holding each other’s hands, we teach one another what each of us knows.” But arrogance played too much of a role, and plays too much of a role. Again, for the reason that people are not willing to come back to their inner micro-fascisms. People are caught within the so called ‘ideological silos,’ though I don’t believe that ideologies exist.

So as I noted, the first thing that was missing is decolonized knowledge education. Number two, was the construction of alternatives. Alternative egalitarian schools, hospitals, and free breakfast programs, like the Panthers, and so on and so forth. And the third, is being prepared to self-defend those initiatives.

Now, it’s not that initiatives did not arise out of Tahrir. Of course, madamasr is a great initiative. I interviewed members of initiatives insofar as queer feminist knowledge production sites, and so on and so forth, social centers…. The permanency was not long lasting given that duree, we’re talking now over 10 years, and the chipping away gradually, let alone the reconstruction and reassertion of space vis-à-vis the State and its collusion with, obviously, neoliberal capital. And what ties both together is the racial dimension because as we know, or as Foucault noted that all States are racist, and as Cedric Robinson, a lot of Black feminists and scholars have talked including Ruthie Gilmore Wilson, Mariame Kaba and so on, that capitalism is racist. It is inherently racial.

So, that is the dilemma, in a certain sense, of Tahrir. The construction of Egyptian identity, nationality… Patriotism, nationalism is what united Egyptian people within itself, and there was nothing beyond that. “Down with the regicide, Mubarak!” Where’s the regicide that exists inside each and every single one of us? That becomes the question.

So when we look at Iran now and the manifestation of what is going on in Iran. Let us also decipher and discern the geopolitical moment in which we are living. Two weeks prior, or about even a week to 10 days prior to these events, we have Ayatollah Khamenie… Ostensibly a lot of rumors, particularly within your American media, claiming that he’s quite ill, he’s on his deathbed, the man is quite old, there’s no doubt that, of course, he’s aging and maybe stuck with illness. But he appeared the following day within Iran, Iranian national media, and basically to reassert the fact that he’s quite fine. God knows best when his time will come, but whenever that may be today, tomorrow, the day after that leaves us with the dilemmas that I noted and I will continue to be speaking about.

We’re also in the moment in which the so called Iranian nuclear deal is being renegotiated. A great deal of asymmetric warfare is already taking place within the region. We have, in a certain sense, US-Wahhabis-Zionist Euro-American Alliance on the one hand, and a so-called Axis of Resistance composed of so-called anti-imperialists like China, like Russia, Syria, of course, Hezbollah, Hamas, and so on and so forth. For a little I’ll leave just Hezbollah & Hamas for a moment simply because I consider these to be more movements than they are State oriented parties, although of course, Hezbollah has Amal (as a political party) … And again, I don’t mean to simplify the equation, but these are the false binaries that exist. This is a geopolitical framing within Islamophobia that is ongoing, within anti-Jewish hatred that is ongoing, and an asymmetric warfare.

Now comes along, peace be upon the prophet Muhammad, Mahsa Amini, and what happened with her. A young girl forced to refix by the so called morality police, her hijab: beaten, account accounts differ. This is the way that we need to think because there’s propaganda going on both sides. Fair enough. People then go out, they revolt, and by the way, on the same day, a 15 year old, Iraqi called Zainab Essam Majed al-Khazali was murdered, and was sniped by a US soldier in Iraq. So, look at what gets airtime here, okay? A wave of uprisings if you will, begins to take place. Now, mind you, there are also millions of people that are supporting the Iranian regime. And they’re out in the streets, and they’re, equally, protesting. Mind you that we had when 20 million people that went out for the funeral of Qasem Soleimani. The question becomes now insofar as Iran, and Iran is a complicated situation, because wilayat al-faqih, or the Iranian State was not meant to be a State within itself. It’s meant to have expansionary desires, impetus particularly in relationship to a concept I talk about in the book, where sovereignty lies, which is the ummah, a non-territorial concept or non-Statist concept and so on and so forth. Fair enough.

In that particular case, we’re seeing the tyrannical State repression being pitted against the opposite “dialectical operative,” your American hetero-patriarchy, homo-nationalism, pink-washing islamophobia on the other side. These are the dynamics that we’re seeing, we’re seeing this embrace, then, by some like actresses, I believe her name was Masih Alinejad. She’s an Iranian actress. She left Iran quite a few years ago. Of course, for repression and persecution and so on, so forth. She’s been outspoken with regards to the hijab, there are many other Muslim women that have been outspoken with regards to the hijab. As far as I’m concerned, all women that are non-Muslim women who dress whatever way that they want. That is not the point. The Hijab is not the symbol of this or that. It’s not the symbol of righteousness or purity or whatever it is. It has it been taken up as a certain symbol of resistance in Algeria. When we look at Bill C 51 and 52 bills in the context of Quebec, where women are being banned from the hijab, the same thing in France under the guise of Laïcité, which is nothing but a secularized Christian ethic that the societies that are based on.

At this particular instance, we see this Iranian actress who has spoken very openly in her support of Zionists, who has very much praised Mike Pompeo, and many, many other secretaries of state and secretaries of war and the US, put out statements… The New York Times writes this article, claiming that she is the point person, the leader of this Iranian uprising. This is the degree of confluence of a mess, of a schizophrenic mess, in which we live. Now, let me ask to my kin who are on the streets in Iran, as I did of my kin who were on the streets in Egypt, let alone the Black Spring Uprisings as Robin D. J. Kelley refers to them insofar as Black Lives Matter: what are the alternatives here? Because I’m not opposed to direct action. Hell, I participated in a lot of direct actions over the course of my life and on the front lines. In the context of Egypt where I’ve had friends that died, friends that have been sniped… Because in Egypt when they, or at least in the Global South, when they point their guns at you, they’re not using simulated weapons, they’re not using blanks. They’re using live ammunition, and they shoot for your eyes to blind you, to cripple you, to debilitate you, to disable you. Besides direct action, which again, street protests serve as cathartic moments of revolt, legitimately so. What are you building as an alternative? What is your plan, as an alternative? What do you create? And or do you simply want to see the downfall of the Iranian state, as you did in Syria? Because, one thing revolutionaries need to also determine, beyond the fact of alternatives, the real blood that was shed, and decolonization is an inherently violent act as Fanon teaches, there is no escaping that. It’s violent at the level of identity, it’s violent the level of its ruthlessness.

One thing that we don’t think through is strategy versus tactics. Now, I’m very much against the Butcher of Damascus, insofar as Bashar Al-Assad, absolutely! And I stand with my kin. But again, my kin did not learn from the previous, insofar as what happened in Egypt, and what happened in Tunis, and Tunis is still a mess. In that particular instant, and if we’re speaking about a revolution, then we need to also understand that in this moment, if you ask me with regards to Syria, I will say, “Absolutely not. No!” Because the consequence in Syria would be, ‘let’s break Syria into different territories.’ The Sunni, the Shiite, the Kurdish, the same thing with [what happened in] Iraq. Something that is unacceptable to me. So what’s the plan here? It doesn’t mean that I condone Bashar Al-Assad, in this particular moment. It means that the culteries, the Wahhabi Salafi’s from Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the Muslim Brotherhood, Israel that was treating Al-Nusra Front of fighters, Jabhat al-Sham now as they refer to themselves on the battlefield, to return them to Syria, need to be taken into consideration by my so-called ‘revolutionary project’ that I wish to see happen.

So, my problem is the fact that a lot of people in the West, in the orientalist West are fetishizing what they see elsewhere. Take the many white anarchists that go and join our Rojava brothers and sisters, with the fight with the Kurds. Tell me are there not enough monsters within US empire that you would have to go to a region that you know very little about? Why don’t you simply stay here? That’s because you can’t face the monster in the mirror. What about the ongoing indigenous genocide? What about the “Afterlife of Slavery,” as Saidiya Hartman referred, in the context of the various things in which you live. But this is Orientalism.

So unfortunately, folks have not learned from what has been going on, and I would argue Sudan is the same, and it stretches across the board. Unless one has… And again, we don’t have to have all the answers. But you have to have a beginning from which you are beginning to lay down a foundation. I don’t remember again… Especially if we’re talking about moving beyond Liberalism, and Progressivism, and again, the liberalism is the Hillary Clinton, Obama, type of politics, representational politics, but I also include progressives in that mix too, like the AOC squad crowd and [Ilhan] Omar, Rashida Talib and so on. That isn’t sufficient, because you’re still buying and building and assimilating and working off the fruits of labor for which the Settler state, Settler Colonialism as a structure is functioning and you’re allowing it to on-go, to continue. And at the expense of whom, might I ask? There is no way whereby Ilhan Omar would be flanked by Angela Davis and begins her speech where she says, “this is a country founded on slavery, on genocide. But look at me, I am the example of the American dream.”

So what can Iran get? They want the fantasy of the American Dream that doesn’t really exist? They want the secular democratic state that doesn’t exist? That becomes the question.

TFSR: Well, thank you for that overview of the situations. You’ve touched on a lot of the ideas from the book that I want to dig a little bit deeper in. Listening to that, though, I’m thinking about this line from June Jordan’s essay, Report from the Bahamas, where she says, “after we get rid of the monsters, we may all want to run in different directions,” which I think is really the ultimate test for so called revolutionaries, because it’s really hard not to want to, or imagine that you have some answer or better way of doing it and impose that on other people.

Then there’s the coming down, what you spoke about, there’s a cathartic moment within the street protest, that involves direct action it could be violent or whatever, there’s something that happens there that seems like the seed of the revolution, but it doesn’t have the material kind of continuity that will lead to a new world. That’s a place that I feel like we’re stuck and rehashing in various places.

But I also think that you’re quite right, in thinking about whatever the Settler anarchists in the US aren’t facing here when they talk about other struggles elsewhere. I think about this a lot in terms of like Israel / Palestine, and the way that that gets talked about. There is ongoing indigenous resistance in Turtle Island. And yet, the way settler anarchists talk about Israel doesn’t face their own complicity within our situation here.

MA: Settlers, as you noted, Scott, the thing with Settlers and white Settlers in particular, the complicities not only within the context of Settler Colonialism, anti-indigenous, and anti-Black, because certainly there’s a lot to be said with regards to that. But the complicity is also an Imperialism. So there’s a double responsibility there. You know, I’m glad that you obviously brought up June Jordan, Fanon. The problem of the “hegemony of hegemony” or a new elite class… It’s very easy from a Marxist-Leninist perspective to take over institutions as opposed to construct alternatives, because then you have to think through, because the institution represents that alternative that you’re supposedly going to engage in some cleansing act with regards to. Although it’s going to be hierarchical, yada, yada, yada, and reproduce all the authoritarian tendencies within itself, and so on and so forth.

But this becomes the challenge, because, as you just noted, decolonization is material, it has to deal with land, it is not a metaphor. It doesn’t have to deal with dealing with school curriculums, decolonizing the Academy, which is a colonial institution, decolonizing laws that are based on Protestant Ethic and so on and so forth. You can’t decolonize what has colonially been established insofar as a governance, insofar is a mode of predatory, parasitic… I don’t want to even say economic exchange, because there’s a difference within our cultures and traditions insofar as markets, for exchange versus Capitalism and what Capitalism actually is. There’s only integrated worldwide capitalism. I’m sorry, like China, Russia, Cuba: nobody is exempt from that Capitalist market, be it through development, be through tourists industry. Sure, some are more of a planned economy manifestation than others, but all societies are Capitalist. And that is the limitation of thinking within that Statist framework to enact that change.

What becomes necessary, wherein the choice is either one of two, you either invest in the dominant order or completely divest from it. Divesting means you need to organize. You need to organize the alternatives, you get to know people, which is very difficult within itself because of insecurities, because of fears, because of misconceptions that we’ve internalized, stereotypes, asymmetries of power that exist amongst us. And what happens if we fail? And the difficulty and challenges of actually creating common communities, solidarities in which people are not tied together by some kind of national identity or some religious or racial belonging, but rather the ethical and political commitments that inform, that should have identified, that should have come with the identities they embrace.

Queer. Somebody telling me that they’re queer means absolutely nothing to me, or an anarchist or Muslim. What are the ethical political commitments that defines your queerness, your Islam, your anarchism. Because there are a lot of Zionist queers, let alone anarchists, let alone Muslims, as a matter of fact. So what are the ethical political commitments? It’s not a matter of bending one’s self or one’s body to the sky five times a day as a Muslim when one is being a patriarchal misogynist to their family, to their wife, yet is okay with looking at a white woman in predominantly non-Muslim society and being able to say, “Oh, hello” back, but when it comes to Muslim women, “I’m not going to say, “As-salamu alaykum“ because I need to supposedly lower my gaze.

So, this is the kind of hypocrisy, unfortunately, that is very much ongoing. This hypocrisy also stretches in the context of migrant Settlers of color, of which a lot are Muslims. Absolutely. Right. And they go out into the streets, and it’s “Free, Free Palestine!” What about us being Zionist or tantamount to being Zionist on the stolen lands? Because we reap the privileges, and sorry, there’s an incommensurability between, as far as I’m concerned, and this is what the book posits, Islam certainly and the world that is constructed within the context of the Settler colony itself, in terms of values are cultures of whiteness, which we’ve all internalized.

So, to me, Whiteness even extends beyond the color of skin. There are white Arabs, there are all kinds of white people that are also people of color, that’s not the point. So thinking about the work that we have to do internally, and collectively, the calling out mechanisms, because again, if we’re talking about building a community that’s very, very tough and difficult, we’re going to have to have very difficult conversations as to what binds us what makes us different, and how do we support one another, and what it is that we’re building in the first place.

TFSR: Yeah. Pulling on some of this, and then getting into the one of the main arguments of your book… I want to pull on this idea of decolonization and decolonial education as a main force in this. Because you sort of start the book out in this kind of false choice between the two different kinds of Muslim identity, let’s say, that sort of created both by Islamophobia and a long history of Orientalism and colonialism, and the reaction to that within certain Muslim spaces. I think this speaks to what you were talking about, about how we end up recreating the hierarchies and institutions.

So, maybe you could talk a little bit about that dichotomy between the kind of liberal Muslim who’s looking for inclusion in the in the Euro nation state, and the reactionary fundamentalist infantilized by Islamophobia?

MA: Well, you and I know, colonialism is violence. Before I come to recognize my name, the value of my name, my own traditions, my own cultures, my own language, I came to fetishize a skin that wasn’t my own. I learned to bleach my skin white, because I wanted to look white, I want to appear white, I want to take on the civilizational values insofar as the dress code, I’m talking surface and depth here, at the level of the superficial surface, the maps on our faces, etc, but also the eyes insofar as the windows of the soul and the depth as far as our values. Because of that trauma, because of the hundreds of years of dispossession, literally so, that we have been very much ongoing through. I would argue, really, since 1492, not just in the context, and of course you know this, not in the context of just the US and Canada, and so far as well. The invasion of the Americas in general, starting with the Caribbean, and the significance of that date and why hence, we need a 1492 project and not just a 1619 [one], but also because what was going on on the other side of the world insofar as Andalusia and the persecution by Ferdinand and Isabella of Muslims and Jews, their murder, their forced conversion, and so on, and so forth.

So, now, we’re talking hundreds of years. Not just since 1798, the Ottoman Empire collapse. We begin to see and particularly for Muslims, I think it was with each successive Crusade, left particular imprints upon Muslims, that only led to their further, if you will, arrogance, hegemony. There’s a lot that can be said over the span of about 1,443 years of Muslim history. And I don’t mean to, again, engage in a reductionist evaluation of that history, because errors were made in my humble opinion, very shortly after the Prophet, peace be upon him, had passed away. We could sit down and get to that in a moment. But if we were to only consider for 1492 onwards, those imprints that happened during the crusades, and that expanded only further with direct occupation of the SWANA regions explicitly.

Of course, there was resistance because again, people of color have agency. But it often led and often manifested in two different forms, either fundamentalist or Orientalist. “I want to be like the civilized Western other.” We have many examples of that, including Muslims, migrant Muslims within the context of Settler colonial societies in which we live. Or alternatively, because of the degree of repression, suppression, oppression that we experienced, because of the lack of education, “I’m going to subsequently engage in wanton, impotent violence that manifests itself as total, as all occupying, and radiates in all directions against even my own kin.” We certainly see it in the context of Iraq, we certainly see it in the context of Syria. Who would have imagined? I certainly did. And you’re going to get a 3.0 and a 4.0, that ISIS would even condemn al Qaeda as being too soft. And the reason is, well, let me rephrase the whole reason thing, because obviously, there is no reason and I’m not condoning ISIS becoming ISIS, but I do ask my liberal Muslims, this: If you were an Iraqi who’s family had been murdered, your wife and your children have been killed, perhaps raped, your land has been dispossessed, you’re living in poverty, you have no education… Would you have joined ISIS? Maybe, maybe not.

There were some things that ISIS spoke to insofar as the collapse of the colonial borders between Iraq and Syria. We have to ask ourselves, why did 100,000’s, of course, again, supported by a lot of regional and geopolitical forces, migrate to this place, what attracted them. The problem with ISIS was the underpinnings of the dream of this ummah, that they wanted to establish the ethical and political commitments within itself. And again, in order to understand that you have to have the knowledge, you have to engage in education. If you don’t, your actions are only going to fall within those two camps: fundamentalist or conservative. There are a lot of those that exist, obviously, even in the context of the US, Canada, a lot of conservative Muslims that sit down, debase the US, every single day. “This is an infidel society, this is a kafir society, this is the this and that.” So my question to them, “Why don’t you leave? And what is your complicity within this so-called infidel society insofar as, again, whose backs it is built upon?”

So there’s a lot of, again, orientalist Muslims or liberal Muslims, let me say this also engage in the same processes. Because within the context of Settler colonialism, this is the interesting part: Settler colonialism does a lot of atrocity, but it does allow an avenue for the re-envisioning or the re-imagination of one’s own sense of identity. Because of the dreamy horizon that it offers: “You’re now in a society in which so-called Freedom reigns.” You can say. You can think. You can do whatever it is that you supposedly want, limited by choices, as we all are. That becomes the issue. But it also becomes an opportunity to seize.

The degree of, if you will, colonization even extends to when I get asked, “Why did you write this book?” You had mentioned the Orwellian theft of language, I’m talking language as it relates to land, as it relates to identity, as it relates to power, and so on and so forth. The degree of colonization is such, if you stop a Muslim on the street and you ask them, “What does Islam mean?” In most likely of cases, 99%, the Muslim world respond back and say, “Oh, it means ‘submission.’” Islam does not mean submission. Islam comes from the root salima, which means you willfully deliver, to deliver based hence upon intellect, upon choice, and to do so willfully. Right? Not blindly, in a submissive docile state as the word submission would suggest. The word for submission actually in Arabic is khudhu.

This is the extent to which Muslims actually know their own language, even Arabic speakers. One can even draw on the concept, or the non-existence of the concept of the State, vis-à-vis a concept that Muslims took from the Qurʾān… Dawla, which doesn’t mean state and because didn’t have a word for state, they started to use it as the term for a State… and so on and so forth. If you ask an Arab speaker, “anarchy.” Anarchism in Arabic is translated as alfawdawia and most likely you were received that response as in to suggest chaos disorder and so on. Whereas the actual word for anarchism where the actual translation, if you will, and hence we’re talking about the politics of translation/mistranslation… Saba Mahmood, Joseph Massad, Sherene Razack and many others. The actual word is la sultawiya, without authority.

So, the crisis of language, the crisis of the absence of proper education, the complexity of the Qurʾān, and our religious traditions that demand a certain impetus and elevation of knowledge, insofar as our own language, which we have been stripped away from, because we’re forced or compelled to learn English prior to learning Arabic… And many, many other reasons lead to these ostensible manifestations of either fundamentalist or Orientalist: “I have to be a good Muslim citizen subject because law abiding that capitulates to the nation state, even if it is a genocidal state, even if it is a slaving state in which I am a part of that enslavement within itself, that I shall pledge my allegiance to the almighty US to defend its borders, to fight if need be by arms. As is part of the Pledge of Allegiance that this paid homage to, whereby liberalism is now crowned gods.” What does that do insofar as the concept of tawid, within itself? Which is the concept that I, as a Muslim, should not worship anything or deify anything but God the Creator, not a nation, not the people, not the state, nothing.

So, that becomes the question. Do Muslims actually understand who they are, and where they’re headed? The crisis with the Muslims is even worse and I don’t mean to romanticize indigenous people, but the indigenous people have been sent to everything from… not only have their land stolen and continued to experience ongoing genocide, the absence of clear water, we can even say that with regards to Flint, Michigan, Black populations and so on and so forth, residential schools, as I mentioned, the stripping away of their mother tongues, because they understood the power of their cultures, their traditions, their spirituality, and so on and so forth, and engaged in a kind of ijtihād of their own making. Muslims, what do we lack? We have our man we have our territories, we’re over a billion people. What do we lack? We have our resources. The Qurʾān comes about and has entire chapters named after the Chapter of the Sun, the Chapter of the Moon, the Chapter of the Bees, the chapter named after non-human life, other-than-human species. What should this indicate? Insofar as Muslim commitments to ecology, insofar as global climate change, and so on and so forth. That becomes the dilemma.

Unless Muslims strive and get to understand who they are, once again, and feel a great deal of pride and dignity, because if colonialism thieves anything, it is our ability to imagine ourselves anew. And yes, we need to re-dream dangerously again. But we’ve been stripped of that pride and dignity with regard to our own traditions… No! I have to constantly, even with Muslims who are Marxist-Leninist, who constantly have to defer to Marxism, and I will include even Muslim anarchists, who constantly feel the need to defer to classical anarchism, in particular, without looking through their own traditions, that arguably are inherently anarchistic. I love anarchism, including, of course, the classical anarchists. But it didn’t start there. There are non-western or non-Euro-American anarchisms that antecedes and precedes classical European anarchism.

So the horizon of imagination, the theft of that, that colonialism engages in is also a contributing factor insofar as the blindedness, the ghushawa, whereby I either become a reactionary conservative because of the degree of psycho-effective trauma that I have experienced. The sense of loss, the sense of disorientation, the sense of wanting a just world but not knowing how to bring it about. And then I have mullahs and so-called imams and this and that doing the interpretation for me, and me becoming sheep, a follower of these wolves, and vice versa, the wolf of the Settler state that I need to follow now and abide. We need to be good hyphenated American citizens: Jewish-American, Muslim-American, Black-American, Indian-American, everybody’s hyphenated except the white American because they’re supposedly the native. They’re just Americans but everybody else is trying to become part of this manifested so called ‘American Dream.’ Sorry, it ain’t no American dream, as Malcolm called it many, many years ago, may he rest in power, “it’s an American fucking nightmare”. Forgive my language.

TFSR: Thanks for laying that out. That made me think also, there’s the legacy of decolonization from the 50’s and 60’s, a lot of that gets romanticized from the leftist point of view. But again, it’s an example of recreating nations and the problems of states that you’ve been detailing. I was also just thinking about the kind of white fascism rising in the United States as a place for desperate people to go just like ISIS would be when you have no way of figuring out how to act against the horrors of the life that you are…. or just losing control over your life even, for more privilege. Like poor white people in the US. We get these false options.

You mentioned the term that you talked about in the book, the anarchic jihād as a method of reading Islam. I want to get to that, what’s the positive way that you’re looking at how a forgotten tradition in Islam that isn’t, as we are told so often inherently authoritarian, violent, misogynistic, homophobic or whatever, that there’s an actual rich tradition buried in there, sometimes unseen, that you want to pull out of anti authoritarianism, of communal care, and so on. Could you talk about the method that you’re proposing? And also some of these core ideas that you see in the Qurʾān and in the teachings?

MA: Thank you. Well, there are as many Islams as there are, in a certain sense, Muslims. So, I just want to take a step back, if you will, because you noted an important point that I think is worthy of at least stopping at, and that is the fantasy of the 50’s and 60’s and 70’s insofar as decolonization and whether it actually happened or not. “The masters tools will never dismantle the masters house” (Audrey Lorde). So the perception that third-worldism, the Bandung conferences, Nasser, Tito, Nehru, Kwame Toure and so on and so forth… Or what was going on within Pan-Africanist and Pan-Arab thought was actually an internalization, I would say, not only of the master tools insofar as the nation states. I mean, Nasser, at a certain point, wanted to combine Egypt, Libya, and Sudan because to him, if you drew around the borders of these through nations, Egypt and Sudan were one nation prior to British partition, and so on and so forth. Obviously, the boundaries of Egypt have morphed tremendously over time, as all nations.

But if you draw around that, you will get the image of a smaller Africa. To him, Egypt represented the labor, Sudan, next to the Fertile Crescent obviously, the land, and Libya, represented the capital. So to him he wanted to have this image of a smaller Africa. We saw an attempt insofar is a fusion between the state of Egypt and the state of Syria that ended up collapsing, that didn’t really last much for lots of different reasons, including geographic space. But a few land reforms and a few gestures to women’s rights do not constitute or undermine the patriarchy in the state because when we look at particularly the context of Egypt.

These land reforms… It displace the Nubian population that existed in Egypt… twice. The Nubians since then have not been able to return to their lands, and returned to their land and carry out their rituals. These are Muslims and Nubian Egyptians, and so on and so forth. They were displaced, obviously, with Sadat, after that, and the building of the Nile dam. There was just an important point, decolonization means completely abandoning the master’s tools and looking back at your own traditions to establish different forms of governance and beyond the rhetoric of socialism.

Moving on to the question that you noted, and forgive me for that digression, but, I do feel that that was an important point to be made, given, as you noted, the romanticization of the 50’s, the 60’s.

Anarchic ijtihād is a methodology that I use to discern ostensibly anti-authoritarian, anti-capitalist, and not just anti, because that’s a rhetorical. But non-capitalist, non-authoritarian concepts and practices that exist visa vie the Qurʾān, because any Muslim or non Muslim will say, “well come show me in the Qurʾān where God says that I need to be an anti-capitalist or anti-sexist or anti-racist, etc.” What I was out to do or was out to do is to provide a reading of the Qurʾān for the oppressed, if you will, Qurʾān for the meek, Qurʾān the way that it was meant to be understood. Because, arguably, all religious traditions and I know this is a generalization because but I do feel it’s a fair one, are built on foundations of social justice periods, otherwise the idea of Prophets was simply to come and to dictate to folks what to do and what not to do, nobody would have followed. There had to be an impetus towards justice that establishes that you convince enough of a critical mass to join this movement. Then after that, you can begin to set down the rules of the guidelines and that becomes more acceptable to folks in such that they were able to fathom, to rationalize, to swallow, and to think through why certain things become forbidden, why certain things become kosher or halal.

Now, an Anarchic ijtihād, and the Qurʾān doesn’t just rely obviously on the Qurʾān refers to the Sunnahs insofar as the practice of the Prophet Isaiah (Alaihis Salam), the Hadiths, the oral tradition, but also it takes liberty and drawing on the thaqafa, insofar as everything pertaining to Islam, insofar as 1,443 years of history. We’re talking everything from manuscripts on astronomy, to the chemistry, to biology, to whatever it is that is relevant and that can be brought to the fore, and to the contemporary present, in order to build this pluriverse. It’s also thaqafa, cultural consciousness, that had been built over 1,443 years of history.

Now there are rules, of course, to ijtihād in a general as well as to anarchic jtihād and I talked about those rules. There’s the rules with regard to the abrogation of certain verses, the context of certain verses, there are even verses that nobody knows the meaning of. The second chapter in the Qurʾān, the chapter of the cow, begins with alif, lam and meem, Arabic letters that conjoin to form an Arabic word that nobody knows the meaning of. There are more blank spaces on the page and there is what is written in black. That becomes the point. This capacity to interpret how and if people can sit down and reinterpret Marxism in so many different dimensions and forms we can certainly interpret our own traditions and have every right.

Ijtihād is a right provided by God, there is this myth that at a certain point, the door to each ijtihād was closed during the Abbasid era. That is not true. Because nobody can stop that process within itself. If I want to engage in ijtihād, if I then want to issue a fatwa, I can go ahead and do so. Whether somebody follows the fatwa, that’s a different question. Salman Rushdie, for instance, the fatwa against him had been since Khomeini. Nobody had gone through with regards to that up until fairly recently. So, it’s a matter of again, that determinant will. If you will, or whether people are convinced by the fatwa or not. People issue fatwas all the time. So that becomes something else or a different dimension.

But the idea becomes to go through the Qurʾān as an Arabic speaker, to focus on the etymology, the ontology, the categories that are created. For instance, the Qurʾān in so many ways, of course, addresses Muslims, and refers to in so many verses, “ya ayhu al-muslimeen w’al muslimat.” But in so many verses, it also refers to “munineen ‘ya ayhu al-mumineen w’al muminat”, or believers, and there are verses in which the Yehud [Jews], Al-Nasara, Sabians, in which the Jews, the Christians, are being told that they themselves let alone to Muslims, that they are safe, on the day of power, that they are believers, that they have fulfilled their covenant in relationship to Allah Subhana Wa Ta’ala.

So, that becomes a question of the category of mumin, of believer… What defines ethical political commitments, insofar as mumin, who and what is a believer? What on the other side defines the kafir, the infidel. Now we, if we look at etymologically, let alone, ontologically, epistemologically at the Qurʾān, the kafir is defined as the one that desecrates the earth destroys the land, engages in musrif, in waste, steals the wealth, of the orphan, of the poor, treats women in ill ways and so on and so forth. This redefines the moniker, the identity in full and what is a Muslim in the first place, let alone who and what does it believer. One is able to then categorize and establish again, certain actions, certain ethics that are related to certain categories, and hence be able to do this re-mapping of again, the Muslim, the believer, the kafir, and so on and so forth.

This becomes a part of the process. Of course, I proceed within the book in order to talk about concepts or anti-authoritarian or non-authoritarian concepts of tawid. For instance, it’s a concept in which I just mentioned: if I worship Allah, the Creator, of which the extension is creation, I shall worship no other master, no nation, no state, no blood ties, not my tribe, not my community, not my children, I shall not run after money, I shall not deify anything, right? I only worship with the commitments, the social justice commitments, that Allah commanded in the Qurʾān. Because Allah said very openly, and I’m paraphrasing here: “if we wanted to create you all, as one nation we could have done so…” walakin (or but),” the verse continues “jaelanakum min shuub w’qabail l’terafu wa’ina akramkum ‘inda allah akramakum” “But we created you from different tribes and different nations so that you may get to know one another, and the best amongst you are those exercise taqwa.”

But what is taqwa, as in piety? Where does it tie into social justice? Ethical political commitments, in terms of fairness, in terms of adala in the world? So, tawid. Now we find a chapter called a chapter of ash-shura, the chapter mutual consultation, how can that not be an anti-authoritarian concept? It is right there as a chapter, very much in line with anarchism insofar as mutual consultation. Then we have ijmaa, community consensus, Then we have maslaha, what is good for the collective welfare of the community within itself.

Islam neither tries to be nepotistic, in the sense of on the far end communist scale nor at the same time viciously parasitic, at the other side of the capitalist, because there are reservations for the responsibilities and rights of the individual and the autonomy of the individual, so long as they do not trespass the collective goods of the community within itself. And while practicing, again, a kind of community engagement, a kind of consensus, a kind of each ijtihād, a kind of responsibility for the other consistently, constantly, and continually.

Of course, then I talk about the authority, or if you will, the place of the Prophet Muhammad ‘wama Muhammad ila rasul an ja’at min qablihi rusul. Muhammad is nothing but a prophet, of which prophets came before them. So, Muhammad’s role becomes also limited, they are a messenger, they are a prophet, they are a rasul, and they are nabi, to convey a message. It is not the fault of God, or Islam, or Muhammad, the fact that the message has been tainted and misconstrued. That becomes vital to not only understand, but also understand to the place of the Prophet insofar as their position.

The Prophet exercised all the anti-authoritarian concepts and practices that I just named. All of them. Consistently and constantly. Because again, the idea was to build a revolutionary community. While Muslims are very persecuted, while they were in Mecca, where the majority of Qureshi community is around them, persecuting them, killing them, and as they migrate that first to Medina, and then after that to Abysinnia under the protection of King Aksum, who was Christian and then later converted to Islam on his deathbed. That becomes, which is modern day Ethiopia, Abysinnia for those who don’t recognize the term.

Then there’s the authority of God, which becomes important to talk about. But Islam is very clear, and the Qurʾān is very clear, there is no compulsion to religion. What would be the point of compelling somebody to believe in something that they don’t necessarily believe in out of fear? That would defy even the purpose of that God wanting that person to believe in the first place.

So those are some of the pillars of what I referred to as an anti-authoritarian and non-authoritarian Islam, if you will. Then I begin to build, of course, the anti-capitalist, non-capitalist tenants of Islam, the redefining of property, because property is not conceived the same way within Islam, arguably, as in Capitalism. Because in Islam, all property belongs to Allah, including our own physical bodies, what we do with them, and so on, and so forth, let alone non-human life. And then all the resources within the land that belong to all of the community to decide on what to do with them. Natural resources are not to be bought and sold. We’re talking about water, we’re talking about natural resources. Everybody deserves a place insofar as a quality of life, and not just the standard of living. Then I begin to talk about Ramadan, fasting, what it means insofar as solidarity with the poor, the alsadaqa that is paid in which it’s not just alms, but that is the rights of the poor over the rich. The way that it’s given is not through a third party intermediary, but has to be given by hand, face to face, so that it creates the kind of solidarity and affinity and a feel for the plight of the poor. Beyuut al-mal, which used to be, if you will, centers that housed resources, food, money, for the poor, to simply go and take what it is that they need, simply so they won’t be driven to sit down and beg and feel the plight and the humility, indignity. Why? Insofar as being homeless on the streets, and having to beg for a right, a human right that everybody should be afforded.

There’s debt forgiveness that exists within Islam. Debt cancellation, because that is a commandment. In fact, it is told in the Qurʾān that one forgives debt, there’s the forbiddens of interest, which is strictly admonished within Qurʾān, within itself a primary pillar of Capitalism. So there’s the contemporary sort of play on beyuut al-maal with Islamic banks. But as I noted before, Islamic banks, as much as the model within itself is interesting, but it also represents an island of halal, if you will, or kosher-ness in an ocean of haram. So it actually does nothing. I mean, it’s very interesting how the model does seek a kind of consensus, that kind of partnership. There’s also the cooperative model that exists between the lender and the borrower, and the person doing or the entity doing the lending, etc, etc, a shared risk factor, and so on and so forth.

But I also begin to talk about concepts like mudārabah, and mashārakah, insofar as shared partnerships, as well as the fact that we as human beings, are khālifs, we are all caretakers of God’s property on Earth. That is it. None of us perse own anything in the quintessential understanding of ownership within itself. So these are some of the concepts and practices that I extract from the Qurʾān, from Islam in general.

TFSR: This is something I think about a lot, is like what makes a sort of approach or reading of something anarchist. You boil it down in a way that it’s something I think about, and it’s the same place I arrive. All it takes is kind of looking at something and thinking about, “how do I engage this to promote mutual care, responsibility, and freedom, and autonomy. That seems like something you’re saying is, is extremely threaded through the the history of Muslim thinking, practice, and writing. I just love that you bring it out that way, in the way you detail it is very clear.

Also just thinking about in the history of at least the three major monotheistic religions that we kind of live under, they all have this story of being this group that was persecuted and was trying to find some kind of safety for themselves. And then and then went on to do atrocious things in various ways.

But I really think that’s a helpful way of thinking. Forming a community that is maybe a minority under the threat of violence as a way to seek social justice, and in that founding moment, thinking of, “how do you deal with other people that aren’t the same as you?” Those two lines that you quoted in the book, “I could have just created everyone the same, but I didn’t.” I just think those those lines are really beautiful.

It’s interesting to think about what gets lost. One of the major points that you look at in the book, or one of the major terms, I guess, is a better way of saying it is ummah, right? This idea of community that can get translated into ideas of state or nation. I wonder if maybe you could tell me what an anarchist ummah, in your interpretation of Islam, is and then how it gets framed, in a more fascist or micro/ macro fascist kind of way?

MA: So, thank you. Again, it’s very enjoyable talking with you, Scott, because the element of pluriversality in a certain sense that you just noted in your last set of comments… All we learn from oppression is learning how to repeat it unless we decolonize it. And the irony is, all these monotheistic traditions started off as oppressed collectivities. Prior to arrogance, rule, and power seducing, and in a certain sense corrupting the original heart and message, of the intent and the action behind it.

You know, it’s it’s difficult to talk about the ummah without talking about the dawla So if you don’t mind, I’m just going to say a few things with regards to the dawla just because of a lot of misconceptions. So, you know, Muslims or non-Muslims alike, like I said earlier, they often repeat and promote the de historicized view that there is such a thing as an Islamic State. There is no such thing as a State that existed in pre modernity simply because it’s a Euro-colonial invention within itself, but we did not have the word for “State.” So Arabs and predominately Arabic speakers, let alone Muslims, now in general will use the post-colonial term dawla to mean State, when it actually does not mean state. Even ISIS refers to itself as a Dawa Islami. So, so much for a Muslim movement that was out to change the world, that knows and claims that it was an authentic kind of Islam actually knowing who and what it is to use the concept of Islamic State, let alone Dawla Islami.

So, obviously, this represents a distortion of dawla meaning. Dawla stems from the verb d-w-l, which morphically as well as somatically falls between two verbs dar and zal, which means to rotate and to go away. The temporality is a part of the understanding of it. Usually what we had within pre modern Muslim modes of governance, several dawlas, even within one dawla. It represented a decentralized model that all composed a part of this ummah, broadly speaking. But they mostly are rotated around connotations of temporality, change, rotation, nothing as much as a fixed order that aspires to, or at least a modern state aspires to.

That’s essential. The condition of well being or the change and alteration of one being from one person to another or between groups. “One day I have my health, the next day I don’t,” that’s part of the understanding of the dawla, it’s subject to change. We can find it in Chapter 59, Chapter of the Gathering, verse seven. The prophets distribution of the spoils of war referred to as a dawla, in a certain sense. “Do not hoard the spoils within only an enclave of you, distribute it amongst the community in its entirety.” The same thing with other verses in the Qurʾān, and the chapter of the House of ‘Imran, for instance, verse 140, that discusses the cyclical nature that I noted of human discitudes, insofar as triumph, one days were usually displaced by defeat, another. will be replaced by, defeat another. So, it ultimately means to turn to alternate, but not to be fixated, it doesn’t have a static place. Organization. Like I said, there are a multiplicity of dawlas, within one dawla, loosely establishing a decentralized confederacy under the rubric of a so called ummah, within itself. Now, a dawla cannot foment and ummah. An example of dawlas that existed for instance, there was the Hamdennite, Mu’ayyad… dawlas within the Abbasid Ummah during that time… There was many ummah. But the fact that you had a seat in Damascus did not mean that you have the Syria, or that you had a seat in Baghdad, did did not mean that you had an Iraq within itself.

The ummah within itself… Because Qurʾān, and God did not lay it down… And this is so fascinating, because the concepts I talked about earlier, are micro anti-authoritarian concepts. Right? The Qurʾān did not lay down a macro structure of governance, it left things loose and it placed the idea of dawla there, and it placed the ideal of ummah. You want to this non territorial concept. Why? because Islam is a message to the world. So it is seeking, and Muslims should be seeking, engagement with those who are like, and are unlike them. Okay, with the spirit that we talked about earlier, insofar as the process of getting to know. If we take that as a foundation, and the ummah structure itself was left loose, and what we saw for the most part through 1,443 years is a decentralized model that existed organically. Sure there was nepotism, sure there was despotism, and so on, and so forth, and gradual hegemony that fed into it. But we have to distinguish between what the decentralized confederacy also allowed. It allowed mobility, there were no politics of citizenship, of surveillance, there were no controlled societies, disciplinary societies in the way that we understand them now. You can contest a despotic ruler by coming up with an interpretation of Islam, that would expose that ruler’s corruption, and so on and so forth. So there was far more means to resist. Power was far more manageable than it is now, it was more far more fluid.

The idea of the ummah that I’m drawing upon is one of the first policies that was established at the Prophet, peace with Muhammad, peace be upon him, established, which is founded on the Medina charter, and the treaty of Hudaybiyyah. It was a multi-faith community, including Jews, Christians, Sabians, and polytheists, in which what bounded this community together was the ethical, political, social justice responsibilities that they had with one another. This was also underneath the understanding of what I spoke about earlier, insofar as there was a nuanced conceptualization amongst the early polity of: it is not a matter of a Muslim/non Muslim, because the person before me is a believer if I choose them as part of my ummah, and they are included, and they are a believer, they are a Mumin. Whether they believe in exactly the same, whether it’s referred to as, forgive me, Yahweh, Adoni, or Allah, or Jesus, or Buddha, or Mother Earth, whatever it is. That’s a name. What’s in a name? Nothing and everything. The everything comes precisely because of the ethical-political commitment, that that Buddha, that Yahweh, that that Alma, whatever, would have us believe in.

So if we begin to think about now, the ummah constructed from that perspective, common community. A community that has a porous membrane, such that it’s able to expand, it’s able to grow, it’s able to mature visa vie folks that are coming in, and folks that are leaving, at the same time equally. As this community interacts with other communities, because the ummahs are often misinterpreted as a nation, which is highly problematic. Because again, the concept of nation within itself doesn’t exist except in contemporary Arabic lexicon. The Qurʾān use the words, qabil and shuub. Qabil are small tribes. shuub are larger populations, so there was indicative of these being more quantitative qualifiers than they were qualitative. And an appreciation for the fact that even small communities, even small tribes, are worthy of not only engagement, and interaction, and exchange with, but if need be, protection from other communities that would oppress those small tribes. And hence that sense of collective responsibilities that folks would share with one another.

So that becomes the idea of the community. There’s one that existed during the early Muslim period, unfortunately, and it began and gradually, of course, to become misconstrued. For instance, we see with the idea of the dhimmites or the dhimmi. Jews being dressed in particular garbs as the dhimmite. Now, the dhimmi is a beautiful concept because it means one whose life, whose neck, if you will, lies within my hands. So, it is worthy of protection. But then we begin to see gradually Muslims, this is 1,000 years later or 1,200 years, wanting to dress Jews or non-Muslims in different garbs in order to distinguish themselves from Muslims and so on and so forth. The beginning of misconstruing, again, beautiful concepts towards ulterior motives that are meant to Other, that are meant to Other and not create an affinity towards, but to create as outcasts. To mark them, to mark their bodies, to mark their traditions, their ways of being and existing within the world.

That’s the concept generally, loosely of ummah, because the concept of khalifite doesn’t, this is worthy of mentioning, doesn’t exist. Again, khalifite is a derivative of the concept of khalifa. And we’re all khalifs in the Qurʾān. The Qurʾān certainly uses khalifa in the plural, just as much as it’s used in the singular. But Abraham, peace be upon him, was described as an ummah onto themselves. So the ummah is a very, also a beautiful concept and term, insofar as again, that extrapolation of what it means for an individual, let alone a body, a communal body, to a body particular, or to embrace particular ethical political commitments grounded in your social justice.

TFSR: Yeah, well, that makes me think. Another sort of strand that you pull out, and it recurs in the book is this idea of hospitality. I think that really connects to what you were just talking about. So I was wondering if you could expand a little bit on that from an anarchist Muslim point of view. Maybe if you have some thoughts about how we can infuse an anarchistic Muslim hospitality into our daily practices, whether or not we are Muslim?

MA: Well the crisis within the Left, as you know my dear, is the fact that we’re really good at tearing each other apart. The Right doesn’t actually have to worry about anything in that respect. They maintain always this unified stance, regardless of MAGA, regardless of Iraq wars, regardless of whatever it may be. Right? The Left? No?

For a while now, more than 15 years ago I started to work on what is referred to within Islam as usul al-ikhtlaf and usul al-dhiyafa , the ethics and politics of disagreement and the politics of hospitality, if you will. How do you offer hospitality the Other? Of course, I draw on Jacques Derrida, a beautiful Jewish Algerian Derrida. Who faced everything, from obviously anti-Jewishness in France, let alone in Algeria itself. So he got hated on both sides of the world. But I also draw on Leela Gandhi. On a lot of other thinkers, if you will, within that process of hospitality.

In Islam, there is such a thing as the ethics of hospitality, insofar as how do you offer hospitality with the Other? Part of it begins with we need to do away with these discussions, because this is no forum. Well, any forum could be used. But can you imagine if we were face to face? If I entered your home, or you entered mine. How the conversation ostensibly, in a very Artaudian way, would have been different. Our gestures in terms of saying hello, the ability to embrace, how we would be seated down, the affect of all that, the offerings of gestures of food, of water, of sustenance, right? Expressions of love, the ability to look the Other in the eye and connect, so that you don’t have to sit at the end of the day across from a dinner table and say, “Honey, what’s wrong, say something!” Out of this fear, this compulsion to speak. You don’t demand the others name, the others name has to be given willfully. It needs to be surrendered. It means that when you are my guest, you are the owner of the home, it means the switch of the playing of the roles. You become, in a certain sense, the commander of the house. Whatever it is that you need. At least traditionally, for three nights, if you will, but obviously, I don’t want to read into things too literally. It could be three nights, it could be longer than that if we’re building community.

We need to give ourselves space, time, which we don’t allow within movement organizing to actually get to know one another. How many times have we went to protests, say Iraq war, or Afghanistan war, even with regard to what’s going on in Iran or otherwise? I can guarantee you and I said this before, the anarchists that went out during the anti-war – Iraq & Afghanistan protests… how many of them went to a mosque? How many of them picked up the Qurʾān? How many of them have spent time with Muslims? How many of them have cooked meals or broke bread with Muslims? How are you supposed to claim that you’re engaged in solidarity? Again, I appreciate the gesture of going out on the streets and being allies that way, but there is no investment in relation. Investing relation means I have to create the space, the time, the opportunity for the process of getting to know, let alone to have an ethics of disagreements by which conflict resolution can begin to manifest and to take place. No two people were aligned 100% insofar is their ethical political commitments.

Say I meet another anarchist or say they meet me. I’m an anti-capitalist, I’m anti-racist, and anti-authoritarian, but you know what? With regards to the queer stuff? “I can’t… I’m not on board with that. I’m not on board with the trans stuff.” Right? The other party has to decide at this point: do we have enough bonds of affinity and am I willing to be patient with Mohamed such that they understand the relevance and importance of gender and sexuality and intimacy, and so on and so forth? And how much patience and time should I give Mohamed, because as Derrida posits: we can’t just have our doors open to everybody, one would not invite the rapist or the misogynist, etc.

But if none of us are pure, we have to allow room for that morphing, and that metamorphosis of the self, indeed our becoming. That becomes the capacity. There is no ideal Muslim. The ideal Muslim is Mohammed, Mohammed died, he left us the practice, and has left us the oral tradition. But we’re also always striving to be ideal Muslims, but we’re never going to reach it. There is no ideal anarchist. Even if you consider, as I was told by a classical anarchist in a conference, this is true, many years ago, Emma Goldman and Bakunin and Kropotkin… I can tell you the context. One of the first times that I was presenting on Islam and anarchism, this is an anarchist that came into the conference dressed in a suit, tie, everything, white of course. He says, “Well, last week we made a whole bunch of effigies of Moses of Jesus and Muhammad and we burned them. What is your opinion with regard to that?” This is over 12 years ago and I said, “Well, I neither know what Moses or Jesus or Muhammad look like besides the blond, blue eyed Jesus, but I don’t mind that Jesus, but sure. I don’t know what Muhammad looks like. If that gives you some sort of cathartic satisfaction. Okay, but I obviously would not do that with our elders. I wouldn’t do that with Emma or Bakunin, right?” He’s like, “Yeah, because these are our gods.” So, so much for ‘no gods, no masters.’

So, that mentality, even if we are to assume that Emma, Bakunin, Kropotkin, and again, they were incredible subjects, subjectivities, personalities that existed, ethically, politically, staunch with regards to social justice that appeared in particular historical period, and all the Jewish background, and we could sit down and talk about sort of the secularization of that, and so on, and so forth. But nonetheless, that embodied certain commitments, that nobody’s perfect. And then even in that case, one is aspiring to be like Emma, like Bakunin, like Kropotkin, like whatever.

There is no ideal stage at which one arrives. One is constantly in the process of metamorphosis, especially if we can see that I have to fight all my inner fascisms. Period. Somebody who’s white has to deal with the same with regard to their white privilege, or whatever else privileges that they have going on. So that becomes, as I noted, the idea, if you will, insofar as the ethics of disagreements. Disagreements… a number them, I believe, four or five, in an essay that I wrote that got published in the Journal of Political Theology, they happen because of ego, they happen because of ideology, they happen because of ignorance and other reasons.

Ideologies don’t exist. No tradition, as much as even a religion. Again, I’m very careful because we didn’t get into the discussion of the difference between religion, faith, and spirituality. These are different concepts. They’re interrelated within the Qurʾān, but they’re not one of the same thing and institutionalized versus non-institutionalized religion, particularly in the context of Judaism and Islam. Because we don’t have a central authority, we don’t have a priesthood and certainly don’t have a Church, you know. So, what that ostensibly then also means, in terms of the ramifications and the repercussions of that? It is reflecting through all these processes of Muslims may claim that Islam responds to everything, but Islam is an engagement with the world and non-human life is an extension of creation and it interacts back.

This is a not a non-thinking religion, and you have to apply it and it depends on space, time and hence ethics. Not just moralities. Here, I mean by you know, Thou shalt not kill or the 10 Commandments. Of course, these are general beautiful commandments, but God forbid if somebody threatens you or I in this particular instance, or moment in which we are collectively together, we reserve the right to self-defense. What that manifests as: we can restrain this person, we use a knife, we use whatever means that are necessary. That’s a whole different other question. But it becomes a question of context, of ethics, and not morality.

Moralities are nice. They’re general commandments that we should abide by. But we have to leave room for ethics, and hence the ethics of disagreements and hospitality, that way, and we lack them. We lack that kind of investment and beyond the liberal multicultural interfaith initiatives, and all that, that really just reinforce the greater macro-fascism and totalitarian orders that already exist.

TFSR: There’s so much I want to talk to you about, but there’s two questions I definitely want to get to, and maybe this will be the last, just to make this digestible for our listeners. Both of my questions really connect to what you were just saying, but one of the major revolutionary liberatory projects of the book is grounded in a decolonial land-based liberatory project, that for you is really important to draw wisdom and solidarity from indigenous movements with diasporic people, like Muslims, Jews, and Black people who are descendants of people from the Atlantic slave trade.

I want to know a little bit more of that vision that you see, where indigeneity and diasporic identities can find connection, and then what the role of the land is in relation to that? That might connect also to your ideas of hospitality, too.

MA: Thank you, thank you very much. That’s a brilliant question.

Indigeneity. I don’t read indigeneity as a racial concept, and it’s very dangerous, in my opinion, to read it as such. I distinguish, of course, between indigenous peoples, indigenous nations, and indigeneity. Indigeneity, I relate to the concept of fitrah within Islam, the inclination to do and being born as good, the inclination to connect with community. When was the ‘I’ in ‘I’, when I was a wee one within in my mother’s womb. That was socialized as this individualist narcissistic ‘I’, this materialist ‘I’. So our inclination is to connect with community, to connect with non human life, prior to us being dressed in pink or blue in a hospital.