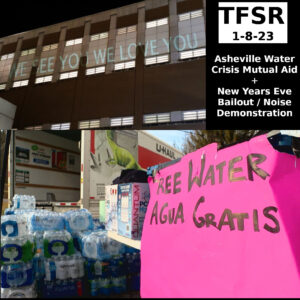

Asheville Water Crisis and New Years Eve Bail Out

This week on the show, we’re sharing two local conversations with community organizers providing mutual aid in Asheville, NC.

2022 NYE Noise Demo & Bailout

First up, we’re sharing a short interview with Beck of Pansy Collective, a queer DIY benefit booking collective responsible for Pansy Fest. Beck talks about the 2022 New Years Eve noise demonstration and bailout that Pansy helped to fundraise for (alongside the Asheville Community Bail Fund), as well as the Buncombe County Jail being reported by the Citizen Times newspaper as the deadliest jail in North Carolina as of January 2021.

Asheville Water Crisis

Then, we you’ll hear Elliot of Asheville Survival Program (Instagram or FB), M of Asheville for Justice and Moira talk about the water crisis that started on December 24th, the city’s response, how mutual aid stepped up to distribute water and more. To read statements by the 16th people facing felony littering and other charges for mutual work and solidarity here in Asheville, check out AVLSolidarity.NoBlogs.Org, or check out our transcripts or episodes from (10/31/21, 12-26-21, 5-15-22) for more words from the groups involved.

Next Week…

We announced that we’d be airing Rhiannon Firth talking with Scott about her recent book, Disaster Anarchy, but we’re putting that off until next week. Patreon supporters can find it released a tiny bit early.

Announcements

20th Balkan Anarchist Bookfair

If you’re in southern Europe, the 20th annual Balkan Anarchist bookfair is coming up from the 7th to 9th of July in Ljubljana, Slovenia. If you want to table or present, submissions are still open and more info can be found at their website, bab2023.EspivBlogs.Net

Fundraising for JJ Ayer Eagle Bear

In prior weeks, listeners heard updates from the struggle against evictions at Winnemucca Indian Colony. Jimmy J, who spoke in the December 25th episode has set up fundraising to help him overwinter via the venmo: @lunaleve

Comrades Conspiracy

There is a fundraiser online to support four anarchists accused by the Greek state of participation in a terrorist group the state is calling “comrades”, a case which has stretched out for nearly 3 years now, and their trial is slated to take place on February 6th of 2023. Learn more at FireFund.Net/Solidarity4Comrades

Leon Benson Fundraiser

We’re happy to announce a re-entry fundraiser for Leon Benson (aka EL Bently 448), a wrongly convicted man in Indiana being organized by IDOC Watch, out of Indiana. Leon was the subject of a chat with his daughter, Koby Blutt, in our May 30th, 2021 episode (audio and transcript available at our website). You can find it at GoFundMe.com by searching Leon Benson.

Eric King Release Fundraiser

There is also a fundraiser going for post-release support for anarchist prisoner Eric King that you can find at GoFundMe.Com

. … . ..

Featured Tracks:

. … . ..

Bail Out Transcription

Beck: I am Beck, I’m with the Pansy Collective. I use they/them pronouns. Yeah, that’s who I am.

The FInal Straw Radio: Cool. And it’s been a long time since we’ve had anyone from Pansy Collective on the show, could you tell us a bit about what y’all do and who you are?

B: Yeah, for sure. So Pansy Collective originally, we had a Pansy Fest, a DIY music festival that was centered on queer and trans folks in the south, pretty similar to Get Better Fest and other regional fests for queer folks to make art and play music. And we also would do political workshops, or educational workshops intermixed with that. We did that for about three years, collaborating with Another Carolina Anarchist Bookfair. And we’re going to be doing another collab this year, it will be the first one since the pandemic started. So, really stoked for that.

But lately, we’ve just been focusing on doing a lot of benefits shows for local organizations and people doing movement work. We’ve been doing the noise demo for about three years. And starting last year, we collaborated with the Asheville Bail Fund, and it launched actually on last New Year’s in technically 2022.

TFSR: I definitely want to talk about that. Would you mind saying a little bit more about what kind of politics Pansy Collective has? I mean, you worked with the anarchists book fair, but the kind of like fundraising that you’ve done in the past. Like I think y’all have worked with Black Mama Bail Out. I really appreciate the fact that you all put on a fun time, as well as platforming artists that are often excluded from other venues, as well as injecting radical politics into queer scenes or into party culture or into like, show life. Could you talk a little bit about how you envision that?

B: Yeah, for sure. So a lot of Pansy Collective got together because we were sick of being at these punk shows with no politics. Just seeing the kind of “anarchist, punk” but like, what the fuck are we actually doing with this energy, with this community? A lot of the times most of our shows are benefits for, like, Black Mama Bailout, with Southerners On New Ground, or, you know, someone needs to fundraise for a gender affirming surgery. We have an abolitionist politic, an anarchist politics, so the things that we fundraise for and do benefits for are usually aligning with that. It’s been cool to kind of bring that back into punk.

We also do all kinds of other music and arts and stuff like that, it’s not just punk stuff. But making sure that we have scenes that are available at all of our shows, and making sure that we’re inviting folks to table and to get people who want to party and have a good time also get connected and plugged into the community. So we often have other friends who are doing stuff around town or in the south come in, plug their work and get people together and plugged in.

TFSR: Awesome. Thanks. So you mentioned the noise demo, this is the New Year’s Eve noise demo that happened on the evening of the 31st. And I wonder if you could talk a bit about your collaboration with the bail fund, how the noise demo went, what it was like, and what the bailout action was like?

B: Yeah, so the last year was when Asheville Community Bail Fund was launched, and so this year, this time around, we wanted to collaborate again. And we have kind of a goal set to bail out 23 people by 2023 — and right now I don’t know where we’re at with that number, I think last we checked it somewhere around 12 or something — but I mean more so than reaching this number of 23 people, it’s keeping the bail fund going.

And so the New Year’s Eve demo is kind of like I mean, it’s an anarchist tradition to go out to the jail, make noise, make people know that they’re seen and loved and they’re not forgotten about. And then also starting last year — not the most recent demo but the-the one last year — it was bailing people out during the actual action. And it was great. This year was awesome. We had a marching band and that was really sick [laughs]. We had a portable PA, it was fucking great, it was really cute. A lot of people showed up, like 100 or so folks.

But that goal of reaching 23 people is continuing on. And also important to note the bail fund is all year round, right? New Year’s Eve is a really great way for people to get plugged in and be like “Oh, remember that thing that’s going on?” to do trainings and stuff like that. So prior to the noise demo we had a jail support training, ways for people to plug in, to join the bail fund and to join organizing throughout the year. Because it doesn’t stop after New Year’s. It’s going to continue to go. And yeah, it was great. It’s always a good time. There’s food, I love making noise in the streets with my friends [laughs]. And getting to see the folks that are inside flashing their lights on and off and waving and knowing that they’re not left alone on this night. That they’re not going to be alone there, they’re gonna get out.

TFSR: Yeah that’s awesome. Especially as the pandemic continues the idea of being stuck in there, and assuming that you’ve even got like a bail option, just maybe not having access to that amount of money at one time seems pretty scary.

You’re an abolitionist collective, not to say that bail funds are necessarily an abolitionist project, but with that in mind — since you’ve supported Black Mama Bailout in the past, this is a running theme for Pansy Collective, which I think is awesome — can you talk about what the intention is there? Just for anyone that doesn’t know about rotating bail funds, like the Asheville one, or the Black Mama one, or the ones that are in an increasing number of places around the country, can you talk about why people go about bailing out folks that aren’t family members, that aren’t loved ones? And what the impact that you understand that to be? Like, what that’s for?

B: Yeah. It’s not an abolitionist practice, right? We’re buying into the cash bail system. And also, no one deserves to be in fucking jail. And so that’s point blank, we’ll do what we gotta do to get you out. And it’s important to note too — it was at least reported last year, I don’t know how long this has been true — but Buncombe County jail has been the deadliest jail in all of North Carolina. Several people have died in that jail due to horrible, horrible abuse and lack of medical treatment. You know, every jail is fucked, but we definitely wanted to highlight that this year and get people out so they don’t fucking die.

This particular bail fund and different bail funds, like Black Mama Bail is getting mama’s out, there’s political prisoner bail funds for folks. This one is just like, “if you’re friend or family member, whoever, is in jail, contact us, and we’re going to work on fundraising to get them out and make sure that they’re set up with care packages and support when they’re out”. But I mean, point blank no one deserves to be in a fucking cage. This is a disgusting, evil system that we’re living in, where people are being caged in and kept away from their loved ones and profited off of so. Yeah, that’s just the basis. No one should be in prison.

TFSR: Yeah. Like the way that the bail system works in this country — or where it operates, because it’s not the same everywhere and not everyone does have have bail — oftentimes there’s this other part of the economy that directly predates on people’s inability to access large sums of money, called bail bonds people, or bail bondsman, or whatever. What bail bonds do is they will put up front, if you pay something like 10%, or 20%, depending on what what it is, or allegedly what your history is with the court system, they’ll put up the full bond if you family or you are willing to pay 10 or 20% non-refundable.

The so-called “justice system” presumes that we need to put a barrier to people necessarily just getting out and committing a crime over and over again, but we don’t want to just hold them pretrial without this access to the outside. So what do we do? We monetize it, and then they make it so that either you don’t get out because you can’t afford the money — or because the the bail system won’t let you out for whatever reason — or you can get out if your family can rustle up a bunch of money that they’re never going to see again so that bonds people can go in and pay it off. And then if you run or if you don’t show up to court or whatever, then they’ll come after you because they’ll be out the rest of that money. But they keep whatever refund happens. Or if someone can just pay it outright.

This is basically what the bail fund is: it’s socializing and collectivizing this attempt to raise the money to pay it off in one go. And then if the court system processes you, you go through your trial or whatever, take your plea, whatever that looks like, the money doesn’t just go into the courts pocket, it doesn’t go into a bail bonds person’s pocket, it goes back into the bail fund, and then they have this money for the next time they want to bail someone out.

So it’s a really interesting way of not only getting people out of that very deadly situation, but also, in a way kind of undermining or short circuiting the class-based assumptions that if you can’t afford to pay bond, you don’t deserve to get out and be with your family, be with your loved ones, whatever, or mount of legal defense for yourself in the run up to your court.

B: Yeah, exactly. Yeah.

TFSR: I don’t think abolition has to be the judgment of if a project is worthwhile or not, I think that’s awesome that you all do that. And for the folks that do get a chance to get out at this event, when people are processed in a timely manner — like I know there’s a lot of bureaucratic stuff that’s going on in the jail that’s making for really long processing times, and really pissing off the magistrates, apparently — but if people get to get out, and then there’s a bunch of people out there with food who are happy to see them, and there to offer them a ride to whatever they need to get to, a phone charger, a cigarette. That’s pretty endearing. It’s pretty lovely.

B: Yeah. Yeah, it was really great when folks are bailed out during the action, when that’s happened before, joining in and grabbing the megaphone and making noise. It’s awesome.

TFSR: Do you have anything to say about what that jail support training that you mentioned was like, or what the purpose of that is? Just for anyone who’s in a community and thinking about starting a bail fund?

B: Yeah. Most of the jail support training is just focused on some of the bureaucratic stuff. So it’s specific to Asheville, but it’s like, what are those steps that you’re gonna go through when bailing someone out? Also what are the supportive things to bring with you? How to make a care package, to get cigarettes, to get some hot food or like, offer a ride to the place that they’re gonna stay? It’s really about understanding the bail system, like you described earlier, and then also what are these tangible things that we need to do? Also how are we deciding who is going to be bailed out, and in what order? Stuff like that.

Most of it really is remembering that we’re not there to judge folks for being incarcerated, and that we’re gonna show up with loving arms and be prepared to have some hard talks, or be [open to people being ] like, “actually, I’m good. I’m just gonna head home. Can you take me home?” To just step into that situation with a lot of compassion and care, and basic necessities too. Because we don’t know whether folks are housed or not, but to show up with that warmth, and those resources being really important.

TFSR: Yeah, for sure. Well it sounds-it sounds like it turned out awesome. Can you, in closing, would you mind saying a few things about where folks can learn more about Pansy Collective and maybe get involved in y’all’s work, or support you through projects like this?

B: Yeah, definitely. We’re on Instagram, mostly, so…God [chuckles in exasperation at social media] you can find us @PansyFest, or you can email us at pansyfestavl@gmail.com. Yeah, definitely hit us up if you’re trying to play a show, if you’ve got something to fundraise for. We’re really down to do whatever. [laughs]

TFSR: Yeah, that’s awesome. Well, thanks Beck. I really appreciate it. Asheville Community Bail is on twitter and instagram and at AvlCommunityBail.carrd.co/

B: Of course, thanks for having me.

. … . ..

Water Crisis Transcription

TFSR: Would you please introduce yourselves with whatever names, preferred pronouns, locations, affiliations, or whatever else you think would be helpful for the listening audience for this conversation?

Moira: Certainly. My name’s Moira. I’m a lifelong resident of Asheville, North Carolina and my pronouns are she/her.

M: And this is M. I’m a member of Asheville For Justice. My pronouns are they/them/elle and I live over here in the West Asheville Candler area.

Elliot: I’m Elliot, my pronouns are he. I also live in the West Asheville Candler area. I’m a street medic and I do stuff with Asheville Survival Program.

TFSR: Cool. M or Elliot, you want to talk about either of your projects that you work with, Asheville For Justice, or Asheville Survival Program, and tell us a little bit about what-what y’all do?

Elliot: Yeah, so Asheville Survival Program began in March 2020 as a response to the COVID pandemic. We established two projects initially: one of them was a free grocery store in a low income neighborhood in West Asheville, and the other we call “streetside”. It’s a coffee and food and gear distribution for homeless folks living downtown. When the city shut down the homeless shelters for several months of the beginning of COVID, we were out every day serving coffee, and then giving people gear. We ran the Free Store and did home deliveries of groceries and household supplies to folks who were affected by the pandemic. And the Free Store just closed in October 2022, streetside is still going strong every weekend.

TFSR: And would you mind saying some stuff about Asheville For Justice?

M: Yeah. So Asheville For Justice also started in 2020 during the uprisings. And funny enough, it was out of the water bottles stabbing shebacle, when APD just ransacked a medic tent that was handing out water bottles. The original members came together with the intention of starting a Black-led, BIPOC-centered mutual aid group. And since then we’ve just been kind of evolving our mutual aid practice. And yeah, it’s been a couple of years now.

TFSR: So as weather patterns intensify, we’re seeing infrastructure failures more and more around the so-called USA and everywhere else. As in the pattern, the capitalist state has peripheries, and those at its various peripheries, or margins, are often the last to get services, or when they do get services, they’re often the lowest quality, and when they get interrupted, those are the margins are often those left out in the dark, or the cold, and hardest hit. So in the week prior to New Year, Asheville and surrounding areas suffered a breakdown of the water infrastructure, I was wondering if y’all could talk a little bit about this. And maybe how geography and elevation have been a part of the water supply issues and getting it back up and running.

Elliot: Yeah, so as far as we can tell, this current water crisis began around December 24 due to a combination of freezing temperatures that caused breaks in local water lines, as well as the shutdown of the outhern water filtration treatment plant. In the Asheville city water systems, there’s the county and there are three filtration plants; two of them are located in the north and remained active. So the northern area, which tends to be the whiter and wealthier area, was less affected by this. The city communication around this crisis was initially, and continues to be, pretty vague and difficult to tell who was impacted, where people were impacted, how many people were impacted. But there was a news article that was released that I saw Wednesday morning, that said, 35,000 people were without water.

I got a tip Tuesday night that this was happening and would be happening for a while, and drafted out a statement to share to local mutual aid groups to request that we get together and start talking about this. But I made the mistake of not sending that out until late Wednesday night, because the city was saying that they were going to be doing water distribution, and I was naive and waited to see what that water distribution would be. It turned out to not be a whole lot actually and we can talk about that. But we got together Thursday on a signal loop and spent all day doing logistics and making phone calls and figuring out how to source water and rounding up donations on Venmo to pay for stuff. And then Friday we started two distro sites, one in Shiloh and one in Candler, that we’ve been staffing through today.

Moira: My understanding of it comes from, my partner works for 211 and so I was listening to my partner going, “this is so nuts, why is the city doing this?” And I was like, “Wait, you mean people both don’t have water, and the city is terrible at getting them water? And they haven’t had water for how many days? [Sighs] Alright I’m going to find out where to get water bottles and try to figure this out”. And then sort of ended up filtering through a bunch of threads to end up connecting with Elliott about this. And as far as geography is concerned, certainly the Asheville water system favors those in the sort of basin of downtown versus the people way out, over a bit of a crest of a hill, like in Candler or South Asheville, or down by the river where it’s always been messed up.

TRSF: Can you say what 211 is?

Moira: Oh 211 is an information and referral service. So if you happen to call 211 with “oh, I would like some water now”, because basically the-the city said, “if you need water, call 211” right? But if you call them, basically 211 is just giving a list to the fire department, and then the fire department drives over and delivers it. The only people they’re doing that for are elderly people, disabled people, and people who are homebound or don’t have a car, don’t have the money to get to water. But then the city tweeted “just anyone call 211!” If you are in the state of North Carolina — or various states, I don’t know how many states have 211 active — and you need resources from various nonprofit groups, 211 is a good contact to connect to you as services in your state. They don’t deliver water.

Elliot: Part of the initial communication from the city, when I was waiting to hear what their water distribution would be, I assumed they would be setting up locations and activating disaster funds to source bottled water, and working with a local relief agency that we have here in town to set up places people could come get water. But what the city said in their initial press conference and on their social media was “sign up for 211 deliveries”, which is not what 211 does. They’re an information referral service. You call 211 if you’re like, “I’m looking for homeless shelters and night, where can I go?”.

We should also include: people in the area who are homeowners who were affected by broken water pipes due to the freezing temperature can call 211 to request help securing funds to repair. But that’s only if you’re a homeowner, right? If you’re a renter, it’s just up to you and your landlord. I think the city’s communication here is a really good example of the idea that in disasters, the state is motivated to maintain control of the narrative and to consolidate power. The state is not here to help you, the state is not here to solve your problems. The state is not here to bring you what you need in a disaster. They’re here to make themselves look better.

And so the city’s communication was initially very vague about where the impacted areas were. They were putting out press releases and saying “from this road to that road”, but they used incorrect road names. It took them until the middle of the week to release a map actually showing the areas that were without water and the areas that had boil water advisories. So during this time, about half of the county was under a boil water advisory. But who knows if people actually knew that was happening. If you happened to have already signed up for the Asheville alerts text message system, you probably got a text message that said it was a boil water advisory. But they only sent that in English, the communication wasn’t bilingual, it wasn’t in Spanish. You can’t text 211 for this stuff, so if you’re deaf, you know, good luck.

The city’s communication was to make themselves look good. It was not to distribute necessary information to people who need it. They were sending out these press releases saying “we’ve used our climate justice map to distribute water to 100 households.” But like, who were those 100 households? Do I know if I’m covered by the climate justice map? If I am — if I look it up online and I find it — how do I know the city is going to bring the water? It wasn’t actually useful for the people who were impacted, it was just a way for them to pat themselves on the back and say that they’re addressing the problem. And it does seem like they kind of shifted responsibility over to 211 to figure out how to solve it. And it’s not 211’s job.

We live in a town that highly prioritizes tourism. You know, we’re “Beer City, USA” or whatever, our whole economy runs on fucking hotels. And the city did not, on December 24 when this began, request that the breweries that are all over town, start bottling water for people. You know? We had folks clearing out the grocery stores buying bottled water for themselves. I heard from somebody three hours away that people were coming to their grocery store clearing out water for themselves. And yet we have all these breweries and bottling facilities. The hotels were fine.

M did you want to say something about the elevation impact?

M: Yeah, I was thinking about the map that they finally put out — bringing it back to the geographical the areas affected versus what the city was saying — where elevation is is definitely a variable on who was getting water as the southern plant get turned back on and how much pressure they were able to give to get houses in higher elevations their water restored. And that’s definitely a factor. But looking at the map that they finally put out, that showed the areas affected, the areas that were not affected, and the areas that were still out, there’s three colors for it: a mixed area of outages and restored, and then one was completely out, and then one was areas unaffected.

It was just really interesting to look at how North Asheville was not affected at all. Elliot, I do remember you saying that there’s two plants in North Asheville, but also North Asheville is higher in elevation. I mean there’s Reynolds Mountain up there, that’s-that’s pretty high up. But North Asheville is very wealthy and wasn’t affected at all. If you look at South Asheville, Shiloh, which is a historically black neighborhood, was one of the last to get their water restored. But if you look across Hendersonville Road to Biltmore Forest, they were not affected at all.

Moira: Not affected at all. Why?

M: We’ve been curious to take maps of the areas that were affected and not affected and lay it over maps of median area income, home values, redlining in Asheville and see where they would correlate there. But yeah, I’m over here in the West Asheville Candler area, which is mostly white, but there are a lot of Latine people here. And unless you, like Elliott was saying, had signed up for those 211 alerts, you would have to check the city website to see what was going on with your water. But then when you sign up for the 211 updates, there was no option for Spanish at all and a lot of people over here are predominantly Spanish speaking. So, yeah, just interesting.

Elliot: The water pressure was slower to resume in areas that are higher elevation, which means if your house is on a hill…like we’re not talking about significant amounts of elevation. So over the past week when we’ve been at these sites, we set up distribution, like little pop up water distro sites, at the Shiloh Community Center and at a church in a Candler / West Asheville neighborhood. And most of the people who are coming through the sites were older, were disabled, had someone in their home with a disability, were taking care of elderly family members. The first couple of days we were in Shiloh, the majority of people who came through had disability placards in their car, and we’re mostly older Black folks.

We were hearing from people every day for the past week, “The city says the water is back on but I don’t have water in my house. I only have a trickle”. We were hearing “My water is back on but I don’t trust it. They said I should boil it.” But you know, household members are immunocompromised, they didn’t feel safe boiling the water. So, I think it was really important for people to have places they could go to get bottled water. So in addition to the 211 debacle, the city was also allowing people to go to local fire departments to pick up water and the fire department would give you, I think a case of bottled water and two gallons to flush. And the YMCAs opened up for showers, which raises the question about who deserves to take a shower, you know? The YMCA doesn’t let you come in and take showers for free if you’re homeless, but they let you come in and take showers for free if your water got caught off.

TFSR: Yeah, yeah, that’s a good point to bring up.

So, we were talking about this happening on the 24th, and Elliot, you had gotten rumblings that this was not going to get resolved right away. At the time of this recording, and at the time of the release in a couple of days — this is Friday the 6th of January — it’ll be two weeks since this. The water department’s website says that water has been restored everywhere, and the way y’all have described is that it’s been a patchwork of various stages of a trickle of water here, or a boil advisory or what have you. Are people still distributing water? Is there a demand for it still, and do you have any sort of information about what sort of pathogens might still be in the water supply?

Elliot: Pathogens is going to be a complicated question to answer.

As far as demand, we were giving out around 120 cases a day in Shiloh and Candler, and then decided to close the Shiloh site on Thursday this week, because their water had resumed largely the day before, fewer people were coming through. We expect to still staff the Candler site today and as of yesterday, Thursday, we gave out another 120 cases of water.

I think what we see in disasters like this is a difference between what the city, what the state says people need, and what people who are experiencing the crisis say they need. And we’re out there to meet the need that people say they have. So I think we intend to continue staffing as long as we have capacity and the ability to source bottled water, as long as people are still coming and asking for it, in spite of what the city is saying.

I did see that the city has released a document describing the recent water testing. They seem to have done a lot of water testing over the past couple of weeks during this crisis. But when you look at the PDF that they’ve released on their website, it doesn’t tell you the address, it just says, like, west or north or south area. And because of the patchwork of issues with this, it’s hard to tell where they actually tested. I think there are going to be a lot of ongoing questions about the safety of different areas, different neighborhoods or specific homes. And I don’t know where people can go to get those answers, especially if you’re renting from a landlord. Whose responsibility that is, or where people can go to get-to get that kind of information.

M: I mean, yeah. Cuz as of yesterday, this area that Elliot and I are in, the boil advisory has been lifted. And yesterday, there were still people coming through without water on, and brown water, milky water. So there’s just a huge difference between what the city is saying and what people in these neighborhoods are actually experiencing. Like, what is milky water? What even is that?

Moira: It feels like the city is actively interrupting people’s ability to get good information at that point, right? Like, “Oh, the water is supposed to be back on, I guess I don’t have to think about it anymore.” Which is just what they’re trying to do, they’re just like, “quit asking us questions”.

Even after the 211 debacle, they switched it over to the water department, who was supposed to be taking the calls. They literally routed calls from City Hall to the water department. The people who are meant to be fixing the problem were the ones who had to work overtime to take people’s calls. So it just feels like, in this attempt to make themselves look better, as is a state’s way, constantly, they have actively interrupted the process of people getting water and good information this whole time.

Elliot: And I think this is a good example of what happens in disasters. It breaks your trust in the capacity of the systems that you rely on every day. I have traveled around a little bit to do disaster relief in different areas, because it’s a skill set I wanted to have. I wanted to learn what it looks like on the ground in places that have been experiencing this for a long time, and what it looks like to do disaster response. And it really hits different when you’re doing it at home.

Those of us who do mutual aid disaster response — so there is an organization called Mutual Aid Disaster Relief, that has helped us a lot with some of logistics around this — and what it’s looked like for me is I’ll take two weeks off of work or a month off of work and go to Jackson, Mississippi, and help build a small scale water filtration system for a neighborhood center down there with Cooperation Jackson. And it’s really different when you can take the time off of work and travel, and focus on doing that work. When it-when it’s happening at home and I’m trying to balance my regular job and washing the dishes and doing laundry and taking care of my kid, it’s a lot harder.

I think a lot of us didn’t expect something like this to happen here, it doesn’t seem like something that could happen at home until it does happen at home. And it feels really lucky to me that we were able to leverage existing mutual aid projects to come up with a response to this. And that we were able to roll out the response very quickly because a lot of us here in the community have been practicing mutual aid, it’s like a muscle that you exercise. I think we can get a little bit lost in the day to day details and logistics and relationships around serving hot food to homeless people: ”is this really making an impact? Where are we going to raise the money next week? How are we going to fix the van?” But I think an important thing to keep in mind is, when you have existing mutual aid projects in your community — kind of regardless of what they’re seeking to address — you’re exercising that muscle, you’re building those habits, you’re building the collective expectation that we know how to solve these problems as a community. Because the city isn’t going to do it, the state isn’t going to take care of us. We say “we keep us safe” and this is what that looks like.

So there’s been a lot of skill building around the sort of invisible labor that goes into mutual aid projects. We were able to round up a signal loop with about a dozen people in it who already know how to do logistics and communication, and how to make decisions together and how to plan and how to communicate about our availability or when we’re not available. And having built the skills over time, and built some of that trust and also built the collective care, expectations, and relationships, I think has made it a lot easier for me, particularly, to balance doing a disaster response and managing the day to day life.

We’ve also talked among ourselves about the idea that this isn’t one disaster that’s going to resolve itself. We’re going to continue seeing this. This is the impact of climate change, right? It was below freezing for several days, it was like two degrees over Christmas, when these lines started breaking. And so some of this is like the tag-on impacts of climate change on our communities, even our fairly wealthy communities, you know, it’s gonna hit all of us.

Moira: It feels like what we need to do is kind of, as climate change keeps rolling on, we’re basically just widening the definition of disaster, right? If every day is a disaster, is it really disaster relief? You know what I mean? How do we react when it’s… Because I imagine a big portion of what caused the outage — of course, this is just my idea of it — is probably that it was like 70 degrees, and then in two days it was 2. That huge shift in temperature, the water system, like any system, doesn’t really like that very much.

People in other countries and other places are experiencing that constantly. And it’s just — we as a country, we have this culture that kind of considers it like, “Oh, but they just had a disaster. Oh, that’s a thing, that’s just one thing.” But no, it just keeps rolling, and it’ll keep being that way. Realizing that disaster relief and disaster work is really just laying the groundwork for what the next 200 years are gonna look like.

M: Right, and the first disaster was colonization. So if we just zoom out a little bit and realize that there are Black and Indigenous communities who have gone without water and resources for a really long time. And Latin American countries who have been impacted by imperialism, who go without water, because of martial law, because of wars that the US started, I mean, we could go on and on. But having something like this happen at home makes me think also about what it looks like to be in solidarity with other communities that have been putting their own systems in place to have clean water, despite. Like Flint, Michigan, and Jackson, Mississippi and Indigenous communities in the Four Corners area.

It is dire out there. 40% of the Navajo Nation doesn’t have running water. It just lights a fire under me to be in solidarity with those communities more, and learn from them, and lift their voices and just figure out what we can do here at home to prepare ourselves and make our connections stronger for when these ongoing effects of climate change continue to affect communities that go underserved anyway, and just not expect the state to do anything at all.

TFSR: Y’all are making really good points and mutual aid is great when bringing services to people when the state is not providing it. However, the state’s usually okay with that to a point because, to bring it back to what was said earlier, the state doesn’t want to lose face that they are the representative and the legitimate source. And so at a certain point, mutual aid can also be a threat to the legitimacy, as M was pointing out, to the continuation of settler colonialism and racialized capitalism and these things. The state, at a certain point, will see something like this as competition. That’s one reason that that kind of solidarity is really important, to put things into perspective and realize where we stand and where we need to stand.

Neighborhoods get treated differently, neighborhoods with different median incomes have been treated differently throughout this and had their services restored, or not lost, throughout it. Currently, there is a an ongoing case against over a dozen people who are alleged to have participated in protests around the lack of public services, the criminalization of houselessness and poverty in Asheville, in Christmas of 2021. People facing felony littering charges, among other things. Those are coming to court very soon. We hope to have some folks to talk about the case soon. But, I wonder if y’all could talk a little bit about repression, how the city has reacted to your efforts, just that sort of thing, and how the press has covered you?

Moira: Let me start by saying: what a wild two Christmases. Makes you want to write, like a —

[Elliot and Moira simultaneously start making up Christmas songs about all the chaos]

Moira: — laaast Christmas —

Elliot: — I got arrested. The second Christmas, he took my water away —

Moira: Wild, [sarcastically] what a fun two things the city can just give you as a gift for Christmas. And it’s like, you know th-they’re always just going to see it as “Oh, that’s a little bit of bad press, I guess”. But like, so many people are furious,

Elliot: WLOS [local Fox affiliate TV station/website] did run a little piece about us. So you said some things about how mutual aid can kind of fill the gaps in state services in a disaster situation. I think if we understand mutual aid as a dual power organizing strategy that has the long term goal of building community resilience, so that we can meet our needs without the state, the trajectory of that is that initially we may be filling the gaps and doing things that the state isn’t providing.

Like when ASP basically took over the role of giving coffee to homeless people downtown when the city closed the shelters due to the pandemic, we come in and we start filling that gap. And then over the year, because we keep showing up, and we’re building relationships, like, real relationships with people, and not just giving them services and checking off boxes — and as a mutual aid project we don’t have barriers to who can get our stuff, we don’t make you prove that you actually deserve it, we just want to give you stuff — as we build those relationships, and as we build power, our projects start to threaten the legitimacy of the state.

This is a dual power trajectory. This is what happened with the Black Panthers, right? You get too strong and they shut you down. And then what we see there — and I assume you’re going to talk about this in the interview that you’re doing later for this segment — we either see repression or cooption. Or both. We see the state making what you’re doing illegal, and then taking over and providing it themselves. And what that’s looked like here in Asheville has been the felony littering defense cases. If you want to read more about that you can go look up Asheville Free Press where I did a lot of riding around it.

In December 2021 there was a demonstration, an art party event that was held in a local park to call on the city to stop evicting homeless camps. And that resulted in a substantial amount of police surveillance and 15-16 people, more than a dozen people, being charged with the crime of felony littering. Which is, in North Carolina, littering more than 500 pounds. This is something that hasn’t been charged in over a decade in Buncombe County, particularly, and is typically charged for businesses that are dumping waste. This charge doesn’t happen when the city evicts a homeless camp. They don’t weigh everything that they steal and throw away when they clear out a homeless camp and then charge people. Our local police officer, Mike Lamb, in January of 2021 specifically said that they don’t do that, that they don’t criminalize homeless camp evictions unless there are anarchists and activists who are resisting. So we’re seeing a bias from the city against — sorry I think that was in January 2020. [sarcastically] 2020 is three years long, so it’s all just the same year, right?

TFSR: 100%. Yes.

Elliot: After that demonstration, calling for the city to stop evicting homeless camps, City Council attempted to secretly pass an ordinance that would outlaw food distribution. And Ashville Free Press, as a local anarchist media outlet, was able to break that story, and public pressure against the city prevented them from actually passing that ordinance. But it was all happening at the same time: these felony littering charges were being issued at the same time that the city was trying to criminalize food sharing, at the same time that a local police officer was giving a presentation to city council saying that all crime downtown was because of homeless people and that they only arrest anarchists and activist.

So we’re seeing that trajectory, from filling the gaps, to building power, to facing state repression. I think that connects back to the thing we were saying about how we’re trying to build resiliency for the long term. We’re trying to exercise mutual aid muscles so that we can continue showing up and continue doing this, because it’s gonna keep happening more frequently. It’s happening every day in places all around the world. I’m sure they’ll pat us on the head for doing this, as long as what we’re doing is filling the gaps without critiquing them too hard. But as soon as we start actually pushing back, that’s when we start seeing repression.

M: Yeah, that’s when they start violently controlling the narrative. And in Asheville, they do do cooptation of mutual aid. One little example that I can think of right now is the SRA, the Socialist Rifle Association, quarterly does these brake light clinics where they change people’s brake lights for free. You just roll up, they do a safety inspection, and change your headlights or your brake light. I think after about a year of doing that Asheville Police Department started with this voucher program where if they pull you over for a brake light, they give you a voucher to get your brake light changed for free. I just thought that was funny and interesting. One little example of cooptation.

Moira: Are you saying —

Elliot: —that’s not the solution we want.

M: No!

Elliot: We don’t want the cops to start changing people’s brake lights. The whole point of those brake light clinics is so the cops will leave you alone when you’re driving around. We don’t want the state to start criminalizing us for doing this water distribution and then start doing it themselves.

M: No, because they’re going to fuck it up. I mean, the whole reason that the SRA does that is because it predominantly affects BIPOC people that get pulled over for not having their brake lights. And if the cops do it, they’re probably going to pull over white folks, give white folks vouchers…they’re not gunna do it with an antiracist approach.

Moira: My image of how these vouchers get used is, “Sure, I’ll give you this brake light voucher if you let me search the car.” That’s the way that they — it’s like everything that they coopt has hooks in it. It’s the school lunch thing: how many families are in debt to the school for school lunch debt, and that school lunch exists because it’s a co-option of the Black Panthers. So they take something, “Oh, this is working. Hold on, let me put this in my program and now I can put hooks on the back of it.”

M: That’s a good example, because the Black Panthers were violently repressed, also. As we’re talking about this it just makes me think of Atlanta and how those recent forest defenders got domestic terrorism charges. So just something to keep an eye on, as mutual aid across the country gets stronger, what else do we have to be prepared for?

Moira: Right? Because it’s only going to get worse, which is only going to cause our mutual aid efforts to gain more necessity. We’re going to need to do it because the state is going to fail to do it. Then because we’re giving out water to people we’re threatening their legitimacy, then they repress us and then pretend to do other things. And it just rolls and rolls and rolls and rolls [voice dwindles]. You know?

Elliot: And so the thing about criminalization and how that’s kind of unprecedented, unexpected in these situations, makes me think about the importance of community care as part of mutual aid. Like I said it hits different when you’re doing it at home, and I’m really lucky that I was able to lean on community members to help step in with my kid, bring me food, help me get laundry done while I was focusing on this. That’s a part of the invisible labor that I think allows mutual aid work to continue and also allows us to be resilient in the face of state repression. I also see community defense is an important part of this. We’re looking at, both the rising impacts of climate change, and rising fascist violence.

December was kind of a hell of a month. We had the substation attack in Moore County where nazis knocked out power for hundreds of thousands of people just because they don’t like the fact that gay people exist. And we’re going to be seeing increasing impacts of fascist violence, climate change, and state repression. And I understand mutual aid is something that allows us to show up and help keep each other safe when these things happen. Bring water when the water system goes out, bring out solar power when the electric goes out, also just do the basic work of taking care of each other so that we can get through it.

TFSR: If people want updates on the Asheville defendant, the Aston Park defendant case, they can check out AvlSolidarity.noblogs.org. Would you all mind plugging where people can find out more about Asheville For Justice, and ASP, or other projects that you’re affiliated with?

M: Yeah, you can follow Asheville For Justice on Instagram, it’s @AshevilleForJustice.

Elliot: ASP is @AvlSurvival on Instagram.

TFSR: Thank you. Thank you, thank you, all three of you. for having this conversation and for sharing all this information. And good luck and thanks a lot for doing what you’re doing. I hope this helps.

Moira: Absolutely.

M: Thank you so much.

Elliot: Thank you