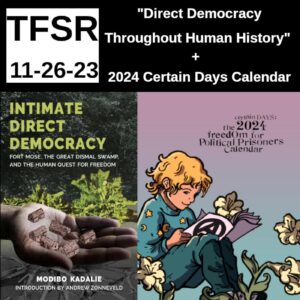

2024 Certain Days Calendar + “Direct Democracy Throughout Human History”

Sara and Josh On Certain Days Calendar

This week on the show, Ian talks to Sara and Josh, organizers from the Certain Days Collective on the publication of this year’s certain days calendar. The two discuss the creative and administrative processes involved in producing one of the most consistent projects in the abolition space. They also discuss the past, present, and future of the project and the constant need to balance short term emergent issues against the long term abolition project. [ 00:02:37 – 00:33:14]

You can learn more at CertainDays.org, find them on a bunch of social media platforms, and order calendars for deliver in Canada via LeftWingBooks.Net or in the USA via BurningBooks.Com and you can find our past conversations with Josh by searching Josh Davidson on our website, including a recent interview about Rattling The Cages.

Direct Democracy Throughout Human History

Then, we’ll be sharing a presentation by Dr. Modibo Kadalie recorded at the 2023 Another Carolina Anarchist Bookfair in so-called Asheville. Modibo is joined by his friend Andrew Zonneveld of On Our Own Authority Books and they share a new bookstore and community space in Stone Mountain, Georgia, known as Community Books. [ 00:34:32- 01:32:30 ]

From the presentation description:

“A scholar-activist with over 60 years of experience in the Civil Rights, Black Power, Pan-African, and Social Ecology movements will discuss the role of critical historiography in the study and documentation of directly democratic communities across human history. Modibo Kadalie’s presentation will touch on ideas discussed in his two most recent books, Pan-African Social Ecology and Intimate Direct Democracy. Dr. Kadalie will also discuss his upcoming book, tentatively titled State Creep: A Critical Historiography.”

Sean Swain

Sean‘s segment on destabilizing the economy with flash mobs can be heard from [ 01:32:32 – 01:40:28 ]

. … . ..

Featured Track:

- For Marmish by Floating Points from Elaenia

. … . ..

Transcription of Certain Days Calendar

TFSR: Hello everyone, if you could please introduce yourselves, and tell us your pronouns, and talk a little bit about your organizing backgrounds and how you came to be involved with Certain Days.

Sara: Josh, why don’t we put you on the spot first?

Josh: Sure. My name is Josh Davidson, he/him pronouns. I’ve been involved in the Certain Days Calendar Collective since about 2015 or so. I was invited by David Gilbert, one of the founding members in prison, and some of the other collective members. I’ve been involved ever since. I do a lot of other political prisoner work, including the children’s art project with political prisoner Oso Blanco, where we take indigenous art and use that on greeting cards to raise money for the Zapatistas. I also work in communications with the Zinn Education Project.

Sara: I am Sara Falconer, she/her pronouns. I’m based in Hamilton, Ontario, the traditional territories of the Haudenosaunee and Mississaugas. I grew up not far from here in the smaller city of Stratford, a wonderful community in so many ways, but I had a lot to learn. So, in high school, a teacher introduced us to the family of Deadly George, an indigenous protester who was killed by police. That was almost 30 years ago now, I guess. It really opened my eyes. So, in the early 2000s, when I moved to Montreal, which had a huge and vibrant anarchist community at the time, I became involved with people that were doing solidarity work. I started writing to prisoners. I became involved in this wonderful group that had started the Certain Days Calendar around then. At first, I was just distributing calendars with my partner, but I soon became involved in the collective and actually creating this beautiful thing. So that’s been well over 20 years now, which is amazing.

TFSR: Can you give a brief overview and maybe a little brief history of what the Certain Days project is and maybe talk a little bit about how it has changed or even stayed the same since its inception?

Josh: Absolutely. So, the Certain Days Freedom for Political Prisoners Calendar is a joint fundraising and educational project between outside organizers across North America and political prisoners in prison. Currently, the incarcerated member within the collective is named Xinachtli. He’s in prison in Texas, where he’s been held in solitary confinement for decades now. The calendar was created over 20 years ago by three New York State political prisoners: Herman Bell, Seth Hayes, and David Gilbert, all of whom have been released as of 2018.

Sara, do you want to add more about the history of the calendar?

Sara: Yeah, absolutely. Josh, you gave a great overview. Herman Bell, who was a Black liberation prisoner, had been visiting with supporters from Montreal at the time, and it was his idea to create the calendar. It was a way to keep prisoners in front of people every day, 365 days a year. Here are prisoners on your wall, a way to learn about our history, even as we continue to shape it. Josh you will laugh, because he said it to you I’m sure many times. He always said to me, “Anyone who doesn’t have a Certain Days calendar on their wall at home or at work is a square.” It’s a major insult from Herman Bell, if you do not have one of these calendars, is that you are a square. I think it really just grew from there.

David and Seth were involved for many years in shaping the project. So many people contributed, including organizing members in New York, Baltimore, now we’ve got Minneapolis, and so many others across Canada and the States. That’s a really interesting thing about the calendar to me too, is it’s just kind of like cross border project, in addition to being across generations, in addition to being across movements. I can’t let the history go by without mentioning our dear friend, Daniel McGowan, friend of this show, who is, I understand, obsessed with Rush, and not so secretly wants to be a Canadian. So, between all of us, we have a lot of fun. We build this thing, and it’s just been wonderful to see it grow. There are people that come in and out of the project over the years in such a wonderful way. It’s just amazing to me that it’s still going, and it feels like it’s gonna keep going.

TFSR: It strikes me as the kind of project where the folks who leave it don’t tend to stray too far from it.

Sara: You’re so right. It’s a collective that’s quite small, and it takes a lot of work. In fact, I took a bit of a step back in the past couple of years because I had to focus on family, and during COVID things were really challenging, too. So, to be able to have that flexibility to take a bit of a step back, but still be so passionate about it and still involved, and to still keep building it. I really value that, and I love people that will step up to take on what they can in the meantime too, so that we can come in and out of it where we see fit.

Josh, like, you’ve seen people coming in and out of the project. You were such a wonderful infusion of energy when you came in too. So, I wonder if you have any reflections on that.

Josh: Yeah, it has really been interesting to watch it grow just in the seven or eight years that I’ve been involved. It’s been really amazing to watch our founding insight collective members come home. I think that’s something that I never expected to see. So, I’m so glad that they’re outside fighting with us today. I think that’s a major change that we’ve seen. But also, just to see new people join the collective, to see how people who were so intimately involved stay connected and stay involved in whatever capacity that they can, it’s really breathtaking, and it’s really amazing to see and to be a part of.

TFSR: I’m really interested in the level of consistency you all have managed year on year. Can you discuss the assembly process, the writing process? I’m assuming it goes on kind of an annual schedule. Can you tell me a little bit about how that works?

Josh: Yeah, you’re right, it is on an annual schedule. It’s kind of a full-time job. We kind of joke about that, but it’s very true. There’s a small group of us doing it, and we do spend a lot of time making it happen. That starts really before the new year. The calendar is available to purchase now, but we’re already thinking about what to do for the 2025 calendar and how that process begins. It is a really long process that includes sending out a call out, which gets people to send in artwork and essays that we then have to select and go through and pick out. Of the many that are submitted, we have to pick out only 12 pieces of art and 12 essays, so that in itself is a difficult process.

Sara: I think because communication to prisoners takes such a long time and has so many barriers, the call out has to go very soon for content. So, we’re in the midst of a high-pressure time right now. There’s only so many months that people think about buying a calendar, to those people that still think about buying a calendar, and it’s now. So, we are really working to get the calendar to stores and distributors and groups and to people who love the project.

At the same time, if we aren’t thinking about next year’s calendar, as a collective, if we aren’t getting in front of the prisoners who might send us our articles next year, they won’t have time to get it to us, and they won’t have time to navigate all of the repressive conditions that they’re under in terms of communication, too. So, this is what’s happening now. I’m sure the collective is thinking about what the next theme is going to be and how to get it out there.

In the spring, you’re gathering those submissions, seeing where there’s gaps in terms of representation, in terms of what they want to see as a vision. Then really soon after that, production is happening, copy edits, layout, chasing people down for high-res images. I’ll give another shout out to Daniel on that one because he was so good at it. All of that so that the calendar can get to print and be in our hands in the fall. Then it just goes and goes and goes.

It’s not a perfect process. I think at certain points, it can feel very frustrating. Then every year the calendar comes out, and it’s just this miracle when you’re holding it in your hand. Josh, you feel this, right? Like “We made this! It happened! We’re gonna do another one!” It’s like childbirth, where you just get that amnesia.

Josh: Absolutely. I’ll just add that it’s nice to hear that you see the consistency over the years in the calendars because every year we do try to update it and improve it in different ways. Whether that’s including photos of books instead of writing books out, adding more dates. We’re constantly changing dates. We were actually contemplating now including the call out in the calendar itself, so that every person that gets a calendar automatically is aware of how and when to submit something. So, we’re constantly thinking about new ways to improve it.

TFSR: Can you talk a little bit about the call out process as it exists now? Maybe talk about the selection process. I’m not sure if the contributors are prompted in any way. Are you looking for representation? Are you looking for timeliness?

Josh: Yeah, we’re looking for all of that. I think that the call out process in itself has changed over the years. When I joined, we had a theme each year, a specific theme, which was considered and analyzed by collective members inside and out. Essays and artwork were supposed to relate to that theme. In the last two years, I believe, we haven’t had a theme, and it’s been a bit more open. That process has had its in and out, its ups and downs. But like Sara said, it’s a never ending process to get things to people inside, while those who are incarcerating them are doing everything possible to prevent anything from getting to them. So that’s something that we’re constantly working against.

Sara: You know that firsthand, Josh, because of this amazing book that you’ve recently released, Rattling the Cages, that the challenges of trying to raise those voices and the importance of helping to break down those barriers. I think that’s one of the most important things we can do as outside organizers is to find spaces to bring those voices into our everyday work and to allow them to be part of what’s happening in our current movements. So, I think, the calendar for the time that I’ve been involved with that it has always prioritized prisoner artists and writers. At the same time, we can’t fill a whole calendar with that work, and we get wonderful submissions from people who are supporters for people from different movements who are interested in supporting the cause. So, it’s such a cool combination of both prisoners and outside supporters in terms of the collaborators.

TFSR: How do you navigate the tension between emergent or urgent issues and speaking to the bigger picture, the long-term concerns of abolition?

Sara: I would say in a way… It’s also a depressing answer, but we are still dealing with many of the same issues that I was looking at when we started the calendar, that the prisoners that we work with were tackling in their communities when they were imprisoned. The current issues and the issues we’ve been dealing with for 20 years plus and beyond, they’re still connected. So more than a tension, I think it’s about drawing continuity across the struggles. Colonialism, racism, sexism, homophobia, repression in inside and outside of prison, something as vital and current right now as the Palestinian struggle. There’s never been a calendar that didn’t focus on that in every single issue of the calendar, as it always will be. I think that it’s almost like a thread running through things to be able to show the history of the struggle that we’re in the midst of.

Josh: Yeah, that’s beautifully said. I think the calendar does a great job of that, of showing that the struggle is the same. These battles and our tactics might change over the years, but it’s all the same struggle against imperialism and against all the things that Sara mentioned before.

TFSR: Speaking to your comment about continuity, can you talk about how involved the founding members are in the production process and the project in general? Can you say a little bit about the intergenerational nature of abolition organizing, both in and out of incarceration? That was one of the things that struck me, was the transmission of information, of radical ideas across generations.

Josh: Yeah, that’s a great question. I’m looking at a photo right now of Sara, Daniel, and I with David Gilbert when we visited him in New York state prison. I think it’s fair to say that this calendar grew out of that intergenerational dialogue that happened between supporters and political prisoners 25 years ago. That conversation is still happening today. I think we’re growing and learning along with them.

Like I said before, it’s amazing to see our founding members outside, to be working with them on the outside. I’m gonna see David in a few weeks in person, which will be the first time I’ve ever seen him not behind prison walls. It’s an ever-growing and ever-evolving process, but it’s great to be a part of that with people who have been involved in struggle for so many decades.

Sara: I agree. 100% on that. From its inception, intergenerational relationships have been core to the project. I was in my 20s at the time, and I’m hella old now. It was formative for me, in my early years as an activist, just being in direct contact with people from the Civil Rights Movement, from the Black Panthers, from the American Indian Movement, from Direct Action in Canada, from student groups and organizations around the world. It’s a tether to me to the reality of our struggles and to how we can be part of still creating that better world that they were working towards. To me, it keeps it very tangible. It keeps me going in the hard times. I hope that we can bring that excitement about this work to new people who join us. I see a lot of growing awareness and interest in recent years around some of these issues.

I want the calendar to be a resource to them. I think it’s so important to bring people along with us. I see the value in all of that. How wonderful to have been able to meet and talk to them and write to them. You know, these voices that could have been lost while they were in prison, and then to be able to see David, Herman, and Seth while he was still alive. He was quite close to us in Buffalo. To be able to spend time with them like that, I feel so lucky to have that connection to people that still want to help make the world a better place.

Josh: Yeah, absolutely. Just to add to that, what Sara’s already mentioned, this calendar, it’s also a catalyst for other projects and for us to learn and grow in other ways. It helps, in part, to lead to this book that Sara helped us create called Rattling the Cages, Oral Histories of North American Political Prisoners, which is due out in December with AK Press. It’s really a conversation, the same as the calendar, between people inside and outside. I interviewed about 40 current or former political prisoners about how they survived and what they learned in prison. Sara wrote a really beautiful introduction, Angela Davis, wrote a foreword. It’s a great book, and I can’t wait for people to read it and for all sorts of people to learn to learn about the calendar through it.

Sara: No pressure at all having to write something that Angela Davis appears in the page before you. I’m so proud, and I’m just so excited, I think to be able to raise those voices in such a cool way, the book is beautiful. I think it’s going to bring a lot more people into this work, which is so cool, Josh.

TFSR: In line with the goals of Certain Days, for the upcoming publication of Rattling the Cages, can you say a little bit more about putting that book together? Also, could you give an update on the upcoming release of Eric King?

Josh: Sure. So, this project, it started as a COVID project. Eric and I were reading a book together, and he came up with the idea of writing to political prisoners to find out what they learned in prison, how they survived, and what they see as far as the future of struggle for our movements.

For those unaware, Eric King is an antifascist political prisoner. He has been doing 10 years in some of the roughest prisons, in solitary confinement, across America for a non-violent act of protest after the police killing of Michael Brown, in Ferguson, MO. Eric is due to be released from prison from the ADX prison, which is the strictest, most secure prison in the US. He is due to be released in February 2024. He is eligible to go to a halfway house now, but they do seem to be keeping him as long as humanly possible. But from this cage, where he has been held, incommunicado from everyone, he came up with this idea, and we reached out to as many people as possible. We really got some amazing and beautiful responses.

TFSR: Thank you very much. So along the lines of both of those projects, I know that they are maybe not necessarily competing priorities, but maybe overlapping ones. How do you think about in terms of these projects bringing new people into the movement versus demonstrating solidarity with those already in it? Like what would constitute a success along those lines?

Sara: I think this is an interesting one. I’ve seen so much change in recent years in the way we can talk about these issues with the so-called general public, From horrible moments that have happened in the states like the murder of George Floyd, to the police brutality against houseless people here in Canada every day, I think more people are just seeing how broken it all is. I think ACAB is hot on TikTok, and it should be. I think there’s a space right now to have these conversations about what abolition looks like, about it being this key line of history that’s not just starting now. I like to see the calendar and the book is resources, so that as people are learning more that they can come into that.

I think also it’s good timing for it because a lot of people in our movements are quite burnt out. This is a fucked up and hard time to be organizing. I can’t go without mentioning just how hard it’s been to organize around the Palestinian struggle. In that space, where I’m talking about how people seem like they’ve come further along with us and then these conversations in recent weeks have been so difficult in the communities. I realized we’re not doing a good enough job of being out there and doing education and making connections. So this is a rambling way of saying, I feel hope, but it’s hard.

TFSR: So, you mentioned that people are latching on to some of these ideas, but as they latch on to radical ideas, I think a lot of people are going to have to drop some old ideas. So, one of the essays that really struck me was the one from Pink Block Montreal. So, my question is, drag defense has become a new front in the wider project of community defense. I was struck by the comment in Pink Block Montreal’s essay in which they stress the priority of holding their radical position among liberals, where they might be tasked with doing community defenses and such at a drag event or something like that. As abolition enters the mainstream discourse, how do you think abolitionists will best bring people to a radical position, rather than having that position be diluted?

Sara: You know, I love that piece in the calendar. If I’m remembering correctly, I think I first saw it on North Shore Counter Info, which is a really great source of local information in Canada, and they share international news too. It really moved me.

In Hamilton, we’ve at times recently been outnumbered by anti-trans and anti-drag protesters, which can be quite demoralizing. But I see people showing up time after time. And as new people come in, I kind of want to meet them where they are. If somebody feels like they have an interest in being involved, but aren’t quite sure about direct action, I don’t think you start at direct action. I certainly didn’t come from a small community. With the values that I knew, I don’t think I would have understood how important it was to stand up and to take risks for the things that we’re doing now. I think that’s okay. I think people come into it where they are. I think that’s why it’s important for us to try and give space for people to develop that awareness and to give space for education and multiple perspectives along the way.

That said, I don’t think that we need to let people block us from doing the stuff that’s more active, and feeling confident in direct action and the important things that needs to happen right now. So, it’s striking that balance, really, between understanding that there’s going to be new people that may not understand all of the tactics and not letting tactics be a thing that divides us.

Josh: Just to add to that, I think the calendar does that well by focusing on education rather than being antagonistic toward towards liberals or such. I think by focusing on education, we’re focusing on this hidden history that you’re not going to find in other calendars, that you’re not going to find in most places. The dates that are throughout our calendar have been submitted to us by people who’ve done decades in prison or from books that are out of print that have obscure prison uprisings and things like that. So, it’s things that you’re not going to find elsewhere. I think the calendar does a good job of providing an opening, no matter what level of political consciousness you’re at.

Sara: I agree. I learn something from it every single year. Even doing the editing and pieces that we do. I always am like, “Wow, that’s so interesting, I didn’t realize I was connected to this other thing. I didn’t realize it was on this day.” I just absolutely love that. I think, because of our wonderful artists and authors that contribute, you can get pulled in by just how gorgeous it is. Who doesn’t want this hopeful thing on the wall?

Years ago, we made a bit of a design decision that we would feature art that felt in terms of color, or tone, mostly hopeful, because we have to look at it for a whole month. So, you can definitely do political art that’s quite intense, or quite negative, and it’s really important, but we try to still have something that is inspirational. If you’re not all the way there, you don’t have to be. You can put up the calendar and be like, “This is a nice-looking calendar.” And then there’s a lot of stuff to think about over the next 12 months.

Josh: In that sense, the calendars really don’t age, you can pick up a calendar from 2010 and learn just as much as you would from picking up one today. I think that’s also something that’s beautiful about the project itself.

TFSR: To hear you describe it, the project and the calendar itself have sort of been on the ascent since the beginning, in terms of you know, technical production and different qualities and honing the message and so forth. What would constitute a leveling up for Certain Days? What are your ambitions for the project in the short term and the long term?

Josh: There’s a lot there. I think I can speak for Daniel when I say that we’d like to sell about a million copies a year. But it is, as we said, very laborious, and there’s only a handful of us putting this out every year. Sara, what do you think?

Sara: I think sustainability. There have been times where we looked at ourselves and said, “Do people still want a paper calendar?” Given the fact that I have my calendar in my hand all the time. The truth is, yes. For people that want something beautiful on the wall, for people that want something that’s like a little slower or more thoughtful about the way that they engage with the calendar.

I know people that still do it. I don’t write in the calendar because I keep all my like dates in my phone. That’s just like how I engage with my day to day. But to me, it still is so wonderful to wake up every day and look at it, see what the occasion was, see what might have happened that could inspire me. Just something tangible is still so cool. I still see a great deal of interest in it, and I think through word of mouth and through people who have supported us, it can continue to grow. I recognize that it’s at a size is now that sustainability is kind of the key. So, a level up really is like 10 years from now, do we still have a paper calendar? I think that’ll be pretty fun.

Josh: Yeah. Yeah, agreed.

TFSR: For my last question. The goal of abolition is obviously a very big goal, very important goal. I imagine it might seem perpetually out of reach at times. So, do you find that you’re able to claim small or incremental victories in this fight? If so, what are those? What keeps you going?

Josh: I think, one, just getting the calendar into people in prison is an accomplishment in and of itself and knowing that people inside will learn and will share it with others inside. Sara, what do you think?

Sara: I think you pointed out earlier, Josh, the releases of prisoners that we’ve worked with for the past decades, that is so encouraging. And it’s the work of people who have put so much blood, sweat, and tears into these campaigns, into continuing to support them, into never letting those names be forgotten. So, I think the fact that people still continue to be released, that we can still put pressure on it, whether it’s for release or for better medical conditions, or for whatever we need to do to keep pushing things forward. I think that that is amazing.

Repression is always tied to the work that we’re doing. It’s tied to the fear that we’re winning, that we’re taking positive steps. The situation in Canada is different, but repression is still ongoing here. Just last night here in Ontario, there were activist raided in their homes related to solidarity for Gaza. It’s terrifying, its bullshit, and we need to keep standing up and to keep raising these voices to let people know that they’re not forgotten, whether they’re in jail or in prison. I think that goes for activists across all of our movements, whether they’ve been in for the horrible decades that some of these folks have, or whether they’re just like new in this system, to let them know that there is a movement out here that is not going to let them be forgotten and not going to let it happen. I think that that, to me, feels like something that we can keep striving for.

TFSR: Thank you both so much for the work that you did on this and for taking the time to talk to me. I really appreciate it.

Josh: Thank you.

Sara: Thank you. This was great.

. … . ..

Transcription of Dr. Kadalie

The following is a presentation recorded on Saturday, August 12, 2023, at the 4th Another Carolina Anarchist Bookfair and so-called Asheville, North Carolina. More recordings can be found at ACABookfair.noblogs.org. A scholar-activist with over six years of experience in civil rights, Black Power, Pan-African, and social ecology movements will discuss the role of critical historiography and the study and documentation of directly democratic communities across human history in conversation with friend and collaborator Andrew Zonneveld. Modibo Kadalie’s presentation will touch on ideas discussed in his two most recent books, Pan-African Social Ecology and Intimate Direct Democracy. Dr. Kadalie will also discuss his upcoming book tentatively titled State Creep: A Critical Historiography.

Scott / Shuli Branson (host): Welcome, everyone. Thank you for your participation in the book fair. I am really happy to see you all here and I’m really excited about this talk. We have Andrew Zonneveld, who is the editor of On Our Own Authority! Press and edited books with Modibo Kadalie, who’s a returning speaker for our bookfair, and we’re really honored to have you here. I’ll let Andrew introduce Modibo further, but thank you so much for being part of this again.

Dr Modibo Kadalie: Thank you.

Host: Also, Andrew and Modibo have a bookstore in Stone Mountain, GA, Community Books, and they also organize the book fair in Atlanta, so inspirations for us. Thank you so much for being here.

Andrew Zonneveld: Thanks, Scott. Thanks, everybody, for being here. I’m gonna be really brief and introduce our honored speaker. I hope you don’t mind, I like what I wrote on the back of this book. Very briefly, Modibo Kadalie is a social ecologist, academic, and lifelong radical organizer. In the 1970s, he was a member of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and the African Liberation Support Committee and a delegate to the 6th Pan-African Congress in Tanzania. He’s also the author of several books. I’m going to tell you a little bit about those. Modibo is going to tell you a lot more about them. Then we’re going to hear from some of your new research that is going into the next book that’s coming out.

The first book (we have one copy left of) was a big collection of Modibo’s notebook writings from the 70s, dealing with a lot of the various movements he was involved in then, a lot of stuff on Pan-Africanism and the African Liberation Support Committee, just a treasure trove of primary source documents. This one, his students compiled, edited, and published back in 2000. That was before we knew each other. About a decade later, when we met, eventually we conspired to do various things. We started a publishing company in 2012, On Our Own Authority! Publishing. This is our little logo over there. We’ve published several books before we did anything of Modibo’s. But one of the earliest books we published was by Kimathi Mohammed, who was a close comrade at Modibo’s. He wrote a very influential pamphlet called Organization and Spontaneity. I regret that we are fresh out of these. But we have this one. You can also find them on our website. This was one of the earliest books that we printed together.

Some years passed doing a lot of other things, and from 2012 to 2019, when we put out this book, we have been doing a lot of community talks and gatherings just like this, mostly around the Atlanta area, but also elsewhere. Modibo was working on a manuscript at the time. But while he was working on that, I started digging through all of the recordings we had from all the conversations and lectures and realized that we had a book there. We could transcribe a book from that. So, while Modibo was working on this book, we went ahead and put out this book. This was the first book of his that we published recently. This is Pan-African Social Ecology: Speeches, Conversations and Essays. It focuses a lot on Modibo’s lifetime of activism, as well as insights into various movements that were going on at the time this was published. It’s got a couple of interviews and a lot of other kinds of public talks and stuff transcribed in there, a lot of great photos. So that’s a great book. People seem to like this book. That was really nice, and it felt good that people received it so well. I think, for a lot of folks, it was a reintroduction to your work.

Most recently, we published Intimate Direct Democracy: Fort Mose, the Great Dismal Swamp, and the Human Quest for Freedom. This is more of a monograph, a piece of writing on history, and really historiography, where Modibo is looking at two Maroon communities, Fort Mose and the Great Dismal Swamp, comparing those, and through that study, asking critical questions about the meaning of history, and how we understand where history is written from and what the study of history has to teach us in our activism. So if you’re interested in any of those books, we can hook you up over here after the talk. Usually, when we have these conversations, Modibo is gonna probably talk a little bit about these works and his upcoming research. And then we just open the floor for questions and get some conversation going. Without further ado, please join me in welcoming our speaker, Dr. Modibo Kadalie.

MK: I’m glad to be here, and to the organizers, thank you. I was here before, but it wasn’t this good. It seems like it’s getting better and better every time. That shows good work. We’ve been inspired by the work of this community here. People coming from far and near just to be with us.

I will take you back through the journey that I had. This book right here is called Internationalism, Pan-Africanism, and the Struggle of Social Classes. What was happening during this time in the early 1970s is that there were a lot of Pan-Africanists, who thought that all Black people were the same people, and there were no classes. They were looking at the state as the way to liberate ourselves. So I tried to address a little bit of that, in their own words. This book is very thick. It has about three different sections, and it answer some critical questions. I was wondering, “Why did capitalism begin in Europe?” It didn’t begin in Africa and didn’t begin in China, though China was a highly developed feudal society. In order to answer the question, I had to re-ask the question. The question wasn’t, “Why did capitalism begin in Europe?” I found out that it began on four continents simultaneously. But I have to go through that process. When you think about things, write them down, follow your stuff, and get yourself out of these conundrums. They can be disjointed sometimes.

Then I joined the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. If you look at the history books, they will say is one of the premier Black radical organizations of the Black Power Movement out of Detroit. The organization that I was a part of was highly hierarchical. They had leaders, and they had us. And they had the middle people—we did the grunt-work and everything. But the leaders were the ones that the newspapers were interviewing. They would have been the ones on television. Then it occurred to me that that was how the history is being written. And that’s not where the history was taking place. So we published a critique of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, Kimathi and myself. Kimathi is a friend of mine who I didn’t even know was a friend because he’s from Savannah. I’m originally from Savannah, GA. And he was in Lansing and I was in… That’s why I asked y’all sometimes, “Where the hell y’all from?” I might know you. I might know who your mommy is. But the point is, I found out this young man named Stanley McClinton. I didn’t know Stanley, but then I was Edward C. Cooper at the time. He didn’t know Edward C. Cooper. But Kimathi and Modibo met. This book right here is called Spontaneity and Organization.

This is what we figured out. The upheaval of the late 1960s, which you read about, you see on TV, see people burning, looting, and all that shit. Then all of a sudden, all these people started organizing. There was this organization and that organization and the other organization. Then all of a sudden, things stopped. Then we began to realize that it was the very organization that was throttling the social movement. So we wanted to figure, what is out the relationship between organization and spontaneity? So we had a conference, and Kimathi presented his critique of the League and showed how it was not going to work. He did a good job. We said that within 10 or 15 years, all these Vanguard parties, all these organizations of Marxist-Leninists, they will fall apart. And of course, y’all are witnesses—it’s fallen apart.

Then there was a hiatus. I was trying to figure out what happened like a lot of people were trying to figure out what happened. I had written some essays, these essays in this book. But we came out with this book, and it really is Andrew’s book. Andrew would follow me around with a mic just like this. And then he called me up and said, “Man, we got a book here.” I said “What?” Our problem was trying to unite Pan-Africanism with social ecology. CLR James, who some call a Pan-Africanist, was talking against the state. But there was nothing in his writing about social ecology at all. But Bookchin, who was a former Trot, he was a social ecologist, but nothing in his [work] about Pan-Africanism at all. So Andrew came up with the idea of naming this Pan-African Social Ecology to hook the thing up, so people would understand it was the same movement. He titled the book and edited the essays and organized essays. It’s a hell of a book. He just used me, but I’m thankful that he used me like this.

In this next one here, he kept insisting that I write something about the Dismal Swamp. I was working on it, but I was saying to myself, “That’s not going to be nothing worth a shit. People don’t want to hear nothing about the Great Dismal Swamp, a bunch of land in eastern North Carolina and southeastern Virginia.” But I did know about the Fort Mose. So I started digging. Then I realized—of course I was already committed to direct democracy—I knew that direct democracy was the only way we have out of this thing. I knew that. But I did not know that the Great Dismal Swamp… The book here catches on really good. People love this book. I’m trying to still figure it out. So I go back and read it. It’s not bad. It flows well. When I read about stuff, I go back and say to myself, you don’t know this guy. You don’t even know none of his relatives, you don’t know anything about him. Plus you heard bad things about him. And the book isn’t shit. So read it and see what you think. So I did that. I said I’m gonna read it. Damn, all these people, they had it right. This was an alright book. What do you think?

AZ: I love that book. I thought the whole process that we went through for that… because we took a long time on that project, because like I said before, that was something you were working on even before we published the…

MK: Yeah, I’d gone to the Swamp, gone down to Fort Mose. Went back to the Swamp, went down to Fort Mose.

AZ: We did a lot of fieldwork.

MK: Yeah, he got his kayak to go down there.

AZ: We did a follow-up as much geographically as we can.

MK: Oh, he’s a map freak too. Loves maps.

AZ: We compiled some maps from other sources. Shout out to Margo for making one of those in there. It’s a remarkable little book. It holds up. We were in it on the editorial process. We were going back and forth. “No, it’s got to be like this.” We butted heads a couple of times on a couple of pieces.

MK: I don’t even remember the butted heads part.

AZ: It’s resulted in clarity.

MK: Yeah, it was a collaborative effort. We were working together closely. We had disagreements of opinion here and there. Some of us conceded here, conceded there. Like on the Zapatistas.

AZ: I agree with everything you wrote about the Zapatistas in that book. You always say that there was a disagreement, but I thought it was a conversation. Yeah.

MK: The Zapatistas evolved to the place where they are now, but at first there were the regular Marxist Leninist nationalist organization. And that’s what I was trying to put forth, that organizations could evolve. Give them a chance, just like people evolve.

Now, I’m gonna tell you about the work I am onto now. This one is called Critical Historiography and State Creep. This is the bomb, this one. I’m going to read you the introduction.

So I’m gonna read you the prospectus from the first section. It reads, “Tragically, the massive body of descriptive and analytical writing that exists today that masquerades as valid human social history is inadequate, ambiguous, inaccurate, and contains an enormous amount of irrelevant information. This in almost all cases is a result of what is being looked at. […]

“Uncritical social history is inadequate because it excludes certain crucial events, as well as certain forms of social relations. Most particularly, they exclude non-hierarchical social relations, as well as the dynamics and social processes that sustain enormously diverse stateless societies.”

What I’m saying basically there is they have it all wrong. They’re looking at the wrong thing. You know who Hammurabi is, who Genghis Khan is, and all these creeps. They’re basically people who social history threw up. They represent the pinnacle of these hierarchical societies. And these hierarchical societies represent a very small portion of human history. The real history lies in the stateless societies that they were trying to suck up. That’s what they were doing, they were sucking them up all over the place. Not only should these people not be glorified, they should be villainized because they were part of the states that were sucking up stuff all over. But the people were struggling against, back and forth and back and forth…

But anyway, this book has two sections. It has a section where there’s a series of essays, which go to the orientation of the book. Then the last section, I choose four highly venerated social formations that I’ve called Classical Empires, and I show you how they rose, how they fell, and how their influence is being exerted through the big religions of our time, even in our time. I spent a lot of time on Greco-Roman civilization because they were the ones that we get language and all the food and everything from, but I show how this was on a Phoenician platform. It gives people stuff to think about. But what it basically does is it employs you to study the unstudied, flat, stateless societies that were part of all our histories.

We need to pick through that and find out how direct democracy is more of a part of human history than hierarchy is. Because when I say, “The way we get past this capitalist society and nation states is we have to talk about direct democracy at the local level,” people say, “Where has that ever existed?” Evidently, it exists all around you. People associate with one another on a volunteer basis, people do it always. I’ll give you an example that I just now figured out. You have to figure this stuff out as you go. Do you remember the crack cocaine epidemic in the black community? Do you remember how the president’s wife was saying, “Just say no to drugs?” That was the bourgeoisie’s answer to it. But black people, young black people, through hip hop music, though all that stuff, organized themselves, and there’s no longer a crack epidemic in our community anymore. It’s gone. We don’t even see it. You wonder what happened. The example that I used to like to give is during the Detroit Rebellion.

AZ: This is in the first book, Pan-African Social Ecology, by the way.

MK: In the Detroit Rebellion, I was in Canada because I didn’t fight in the Vietnam War. I went to Canada. I realized I went to Canada in 1965. If I did the research, I was one of the first ones that went up there, but I didn’t know that. I was doing what I thought I needed to do. But anyway, I had a cousin named Sam who lived right off 12th Street, which is now Rosa Parks Boulevard. 12th Street was the epicenter of the 1967 Rebellion as their history records it. So I went over. I tried to get in during the Rebellion itself, but the border was closed, so I couldn’t get in. I could see Detroit from the Ambassador Bridge, up in smoke.

I finally got in after the thing was settled, and the police had basically repressed the social emotion. So I went to Sam’s house, and I said, “Sam, what happened?” He said, “Man, the n*ggers went crazy.” I said, “Is that right? What happened?” He said, “You see that store up on the corner? They took all the food out of the store.” I said, “What did they do with the food?” “Well, they gave it to the old ladies down the street.” I said, “Well who else did they give it too?” “They gave it to the old ladies first…” I said, “Sam, did you get any?” He said, “Well, they didn’t give me too much,” and he opened his refrigerator. I said, “Sam, how long did it take them to do that?” He said, “They went into that store and within four hours, all the food was gone.” I said, “How did they do that?” He said, “They had chained the line, passing things out, passing things out.” “Well how did they give it to all these people?” He said they had go-carts, driving them down the street, giving it to people. I said, “Sam, these people did that themselves, didn’t they?” “They didn’t know what they were doing. They were just out there yelling and screaming.”

But that was self-organization. Nobody writes about it. Nobody even sees it. They just see the police come in and all that. And you feel bad about it sometimes when you see things right in front of you. And you realize that I missed it. I missed it. But it’s all around. It’s not mystical. In my manuscript, I said (this is one of my best lines, I think), “After all, the unknown is the temporarily hidden.” That’s a good line, right? So I ask you to look at these and read the new book when, hopefully y’all invite us back next year, we’ll have that manuscript in place. I’ll be glad to share it with you. I wish I could give it to you, but it costs money. So I hope I’ve pointed us in a direction. We’re almost halfway down.

AZ: I wanted to ask you a quick follow-up question. Just to clarify a couple of points on two terms, critical historiography and direct democracy. Specifically, looking at critical historiography, I’m wondering if you could talk a little bit about Fort Mose since we have that book with us. And let people know, who are not familiar with the book, why studying Fort Mose in the way that you did is an exercise in critical historiography. Because there’s one way that the history is written, and there’s a whole other way that you’re approaching that story, which leads to a different set of conclusions about how that site organized itself.

MK: Yeah. The non-critical historiography of the Fort Mose site is that the Spanish organized this community in front of St. Augustine for security purposes, and that these people had nothing to do with it, that the Spanish organized it themselves. The Spanish governors, Montiano and these other guys, decided that they needed to have this buffer zone there to protect themselves against the British incursion coming south. Even from the beginning, these people who formed Fort Mose left Charlestown.

AZ: We should clarify, just in case anyone’s not familiar, that Fort Mose was a fort just two miles north of St. Augustine, in Spanish Florida.

MK: And you can see it. It’s actually preserved by some local historians who are not trained in academia. They organized themselves to preserve that site. So that’s an exercise in self-organization right there. The story is that when these people came, the Spanish gave them sanctuary when they became Catholics. What was happening was, so many people would coming, they had to do something with the people. So what they did was put one of the captains in charge of creating something away from the site, away from direct St. Augustine, and they were forced to change the policy. That’s another important point. The state does not make policy on its own. It is forced to make that policy from below. It has to do it in order to maintain itself. Andrew, do you want to say something else about that?

AZ: Just to clarify what you were just saying, we have this migration of people fleeing slavery in the Carolina colonies, coming through the territory that would eventually become Georgia (which was a contested area), and settling in a town just two miles north of St. Augustine, which was the major Spanish colonial urban development. Just to get at what you were saying about the different ways that that story is told is that when you hear this story of Fort Mose from anybody else besides Modibo, what you’re going to hear is that this was, like he said, the Spanish policy that was made to entice people to move south to escape slavery in order to economically screw with the British, which is definitely an effect of people fleeing slavery and moving south to Spanish Florida. But Modibo contends that this migration was already happening, and the specific reasons that are laid out in the book as to why people… because it’s very important to know that the first underground railroad went south, not north.

MK: And then the other thing about the Seminoles. The Seminoles are actually not Native people in the truest sense. The state policy made them native so that they could move this integrated…. I think you make that point in your book. I’m very influenced by these two writers over here. I read their stuff. I hope y’all put some more shit out so I can read it.

AZ: One thing that you never hear in a lot of the books on Fort Mose is where this name Mose comes from. It’s written Mose, and no accent on the E. Everybody’s like “Okay, it’s Spanish, so we will pronounce that Mose.” Because I assume it’s a Spanish name. But it’s not a Spanish name. If you look at old maps, which we did in the book We found some good old maps around, and we even found one other historian who had commented on this. If you look at the old maps, the English maps, they call it Fort Moosa. Then there’s another Spanish map that calls it Fort Musa, Musa being the Arabic for Moses. So these were people from West Africa, who were Muslims, who had been kidnapped, trafficked, enslaved, and escaped and named their city that they founded Fort Musa. Just that one fact alone tells you a lot more about what this community was and the self-organization behind it. It dismantles this whole idea of it being a state project from Spain. In the history of Maroon communities that we read, sometimes Fort Mose is skipped over and not considered a Maroon community because of its relationship to the state. I think that’s not fair. I think that it’s certainly a different and more urban maroon community.

MK: What I’m asking for y’all is helping in writing this new critical history, this critical historiography, because we got a lot of work to do. Because it’s all this stuff, it is turned upside down. Because there are people, even people who call themselves revolutionary nationalists, who draw on this tradition of hierarchy to justify what they do. But that’s not human history at all. Human history is made up of people organizing themselves in a non-hierarchical fashion and resisting the state at every turn States win sometimes, and sometimes they lose. In the time that they lose, you can see that. They always say “Yes, and we were invaded by these barbarians from the mountains.” If you read The Levant, they don’t even know what the hell these people were. These people organized. There were all of these islands in the Mediterranean. They call them the sea people. They came over and knocked out all the states, flattened their asses right on out. But then they say, “Oh, this is a Dark Age. Dark Ages of Cretan descendants,” of whatever, whichever. These were the times when the people were really organizing and working together. And all kinds of human ingenuity and human science emerged from that context. Even the women who were regarded as witches were actually doing all kinds of medicinal things in these contexts. So we need to write that. Be careful, because sometimes you think you’re writing something, and it’s so severe. I remember one time I was writing something, I was going back to read what I had there, and I saw hierarchy in my own stuff. When you do that, you got to start all over again, to get it out of there.

I usually begin these sessions by asking people questions about what they believe. How many of y’all believe Hammurabi was in great king? But I don’t have to ask you, I know what y’all are.

AZ: Does anybody have any thoughts? I know we are a little informal today. Is there anything sparkling anybody’s interest or have any questions for Modibo?

Audience Member 1: What does direct democracy mean to you?

MK: Direct democracy is when people sit down together, face-to-face, and govern themselves by collective decision-making of whatever they come up with. They’re solving their own problems, it’s equal, it’s intimate. You have to know the people. You got to know who their mama is, what they did, what their motivation is, and then you can come up with a decision. What I’m proposing is that we go to the city councils—and I’m glad you’re having this in this library. We need to reclaim these spaces. It’s taxpayers’ money. Library people, they love it. And they like to see people coming forward to have book fairs in their library because it’s your library. So direct democracy means an institutionalized mechanism by which everybody has an equal say and an equal influence in directing the motion of the society of which they are part. It’s not representative democracy now. That’s the first thing I do, I juxtapose it in this new book. I juxtapose it between direct democracy and representative democracy. There is no intervening representative, no corruption, no layer of people who know it all who will come down and just listen to you. You’re the ones who tell them what to do.

AZ: There’s an excellent book that we actually are privileged enough to be featured in that Cindy Milstein edited called Deciding for Ourselves: The Promise of Direct Democracy, and they probably have it at Firestorm. That’s my favorite book ever. So go to Firestorm, and get a copy of it. Some great examples of modern-day real-life direct democracy in action. Hopefully, you love it.

MK: And practice and get it because sometimes you practice and you mess up, so you have to correct it when you mess up.

AZ: Do you want to talk a little bit about social intimacy and why you came up with this term, intimate direct democracy?

MK: Well, it’s intimate because people have to know one another. The Seminoles were actually influenced by the Muskogee, and the anthropologists were saying the Muckogee were a matriarchal society because the matriarch chooses the miko. They call him a chief, but he ain’t no chief. He’s just a person who sits in the council and listens and is a proto-administrator. Because sometimes, in those gatherings, people don’t even listen to the miko. But the point is, that these people who appoint the miko, or at least they consult in the appointment of the miko, are all the women in the society. And they know the kids, they know what they were when they were kids. They know he was a thief when he was a child, so he doesn’t get to be the miko. So that’s the way that those societies work.

I know y’all know about Cahokia. Me and my lover Janice went over to see Cahokia. How many of y’all have been to Cahokia? That was a great hierarchical society, like Okmulgee, a real hierarchical society. The anthropological data shows that people were fleeing those kinds of societies, as opposed to going there and joining them. These societies were unstable, people were being punished. People left there. You see traces of those societies up and down the rivers. That’s why the Creek Indians were called Creek, but they are really Muskogee. You see in West Africa too. My Black Pan-African friends, “Oh, we had great kings and queens.” You’ve being trapped. We’re not for kings and queens, whatever color they are. We had the great societies in Ghana, Mali, and Songhai, and the archaeological records show that people running to the coast trying to get away from these people. Great Mensa Musa, the richest man in the world, who the hell wants to know about that? That’s what I’m talking about, irrelevance. Mensa Musa, he had 100 elephants. What the fuck? …

AZ: That’s a huge part of the book Intimate Direct Democracy. What Modibo does in that book is shows that this eastward migration of people away from centers of hierarchical governance in the Americas, and the westward migration—both towards coasts—that was happening in West Africa at the same time. Due to the violence of colonialism and slavery, these democratic tendencies emerging from these two different places, these indigenous democratic tendencies, meet each other in the Maroon communities.

MK: Yes, and they work it out. It’s just an amazing story. It’s so beautiful when you know it.

AZ: And honestly, nobody else in the world but you would have…

MK: No, no, no, there are people who could see that shit. I wrote it down, and you edited it, and we got it here and we are talking about it.

Saralee Stafford: I don’t often get to hear you Modibo talk about your thoughts…

MK: Saralee is the most influential contemporary writers of direct democratic contemporary history around.

Saralee: Maybe if I stop being a nurse, I could write better. I haven’t really gotten to hear you talk a lot about the situations going on in Georgia right now. I am really interested in what you think about the future of what we have left and the struggle against Cop City, but I’m also wondering, given all of the history that you’ve helped unearth and really just pull together to help us actually think about even how to think about Fort Mose, not just pass it along and be like “Oh, there’s some site.” What’s coming up, the threat of Okefenokee, what do you think it would really take for Okefenokee to not get mined, for the Sea Islands to be returned to the descendants of the enslaved and colonized, and for a Cop City to not get built? What do you really think it’s going to take at this moment, and using all of that history that you’ve shared with us about that is so specific to Southeast Georgia, to Atlanta? Where do you see us going with these struggles? How can we win?

MK: Well, winning and losing is a long-term proposition. But first, we ought to congratulate the people who developed this campaign to save the Atlanta Forest. That will prove to be one of our most significant campaigns in this period. I don’t have any doubt about it because there are so many layers coming together and congealing over the question. I think what is happening, just to give you an idea, they have overcome the civil rights petty bourgeoisie and their backwardness in the spirit. And you overcome that, then you’ve gone a long way because they’re scared now. They are backing away. But you have to keep the pressure on, and I’m not a prophet or soothsayer or nothing. But I’ve never seen anything as promising as this. And everybody understands it. The thing that I love about it is the young people that are doing it. It’s not old crackpot preachers, which all the streets in the city of Atlanta are named after. That’s a bad situation there between the crackpot preachers who have the streets named after them and the Stone Mountain named after the damn Confederates up on the wall. All of this stuff is gonna be wiped away after a while, but it’s a long-term struggle. It’s not the day or tomorrow, one fine day. It’s going to take many different turns. It’s going to take much frustration and much anguish and a whole lot of elation when you win a little bit. So the dynamic of back and forth, I think we are in a good position. I think people understand that.

Now, Okefenokee, it is remote. The people around there, the small-town city municipalities are bought off. But we’ve been down there. There was another mining group that was going 8-10 years ago. I got a crackpot preacher, who is a comrade of mine. Some crackpot preachers can scare people. So this was the Reverend Zach Lyde. We went down there, and we raised a little hell, and that postpone it a little bit. But they come back because there’s money to be made from that kind of stuff, especially now. This is the dilemma and conundrum. On the one hand, we want to decrease fossil fuels and increase clean energy. That requires all kinds of elements, like cobalt and all these other things, which can be mined, and people can make money from. Two of them, unfortunately, can be mined at Okefenokee. But once we realize that the quality of life is going to be increased by having a clean planet. And to people who are from the outside, they tried to pull the thing about being from the outside. What do you want us to… We can’t breathe your air? We can’t drink your water? But the point is it’s a long-term struggle. It goes from generation to generation. The new generation will bring us closer to a new understanding of it all. Because there are some blind alleys we can go up, causing great catastrophic damage. So we have to be careful. We have to write this stuff. But once we write the history down and show that people, everyday ordinary people, are the ones who make history, then they can see themselves. We don’t want to tell the people to do this or that, or to grab the people by the hand and lead. We want to just put a mirror up to them. So they can see who they are and what they did, what they must do. Once they see that then they can understand. You need to just step aside and join in.

AZ: We have a piece of writing in the works dealing with Okefenokee that’s trying to accomplish… The ecological destruction around Cop City is obviously horrible. The potential for what is going to happen in Okefenokee is unparalleled. This is one of the last intact freshwater ecosystems on the planet—not in North America, not in GA, on planet Earth—that’s still functioning in a way relatively similar to the way it was before the Industrial Revolution, which is, I believe, the standard for how you determine an intact freshwater ecosystem. Drinking water comes from there, but several species make their home there including some endangered species. On the social aspect, it’s really important to know that the Okefenokee was one of these places in this contested area that became Georgia. It was a place where people sought refuge. It was really the gateway to the Suwannee River for maroons and people fleeing slavery. Basically, there are two rivers. There’s the St. Marys that goes out to the sea—which by the way, anything that happens at Okefenokee ends up screwing up Cumberland Island, which is another protected area just downriver. Then the other river is the Suwannee River, which goes down through Florida.

Now, if you look at the great maps in a book I’m reading right now. We’ll probably talk more about this in another event at some point, but you can look at maps of maroon communities in Florida, just going right down the Suwanee river. Then even further, once those folks began to be threatened, they moved farther south by sea. But that whole area has such a history of struggle, such a rich history of struggle, and a multiracial struggle. In these communities that lived there, there were African people fleeing slavery, there were indigenous people who were the first like the Timucua and Muskogee. And there’s remarkable gender history there as well. The Timucua, the Spanish were like “We don’t know what’s going on with gender here.” It’s like they couldn’t figure it out. It’s really fascinating. You should look at it. There’s a huge Two-Spirit history in the area. And that history of Okefenokee, a lot of stuff is written about it, but it hasn’t really been presented as part of the effort to preserve that site, as far as I’ve seen it. And I think that part of the struggle is going to be presenting the people… The people down there right now, in Waycross and Folkston, it’s Trumpville down there, no joke. It’s gonna take people thinking and learning about how to engage with folks. While they might be objectionable folks in a lot of ways, they also don’t want to lose the Okefenokee. They’re very concerned about it. So maybe even with their kids, if they have access to stories from this place that show these multifaceted liberation movements that again and again and again kept happening in that area, I think that’s a resource that can be brought to bear.

MK: It’s very important that y’all do the writing from a critical ecological perspective and critical historiographic perspective. It’s needed.

Audience Member 2: Thank you so much for the talk. I’m curious, you mentioned a couple of case studies in the book, like the idea of migration. But what other types of historiographic examples are you talking about? Specifically, you brought up this idea of showing a mirror to the masses. Are there other examples of that in the upcoming book?

MK: In the second section, I choose four empires, real empires. That’s another weakness of the older literature. Anytime there’s an amalgamation of several different nations, city-states, they call it, the guy who controls all three or four of them is called an emperor. But what I’m talking about is the ones that emerged out of Qin and Han China, where you got 4-5 million people coming together and being administered through state religions. That’s one example. Another example is Achaemenid Empire, which was the ancient Persian Empire. Then I show how that sucked up a lot of other nations or other small tribal identity groups around to make up that administered… but they had to be administered through these great religions. I talk about the great religions, the Great Western religions, the monotheistic religions of ancient Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, that’s the same religious tree. Then I talk about Hinduism and Vedic writing, and I show how they use that to mobilize people and break down these flat societies that they had to mobilize. Another thing they had to do—and you can see it resonated in the questions of my own time—all these religions had to use women’s bodies. And there is really no real question in my mind about it, because they were not industrialized, they used manual labor.

So you have to have a massive amount of manual laborers, and they use women’s bodies to create this. Not only did they use women’s bodies, they used the artisans. So if they wanted to decimate a flat society, they went and killed all the men and grabbed the women—because they were using them for laborers and bodies—and they would take the artisans and pay them off. And then they assimilated them into hierarchies. So I demonstrate that process and how it takes place in these various regions, including the Greco-Roman Empire. And the Greco-Roman Empire was the worst of them all. I liked what I did there. This stuff is still resonating. Once people see that it’s resonating from situations like that, because most people will look at history and they’ll say, “Well, I know Roman history, because I knew about Julius Caesar.” Julius Caesar is worth shit. The point is they had consolidated a massive empire. These people were buying and selling everything—women, children, everything. In the introduction to the second part, I say that what is being presented to us is a cavalcade of individual heroes. And I don’t spare nobody. I talk about Ragnar. I mentioned them all on the list. I say they’re all equally unimportant. I put Hitler and Ragnar and George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, all of them in there. I had some fun with it. If I were to present this at a school, and I tried to present this as a thesis, the people would say I went crazy. That’s why we publish our own stuff.

AZ: We have to wrap up.

MK: Sorry, y’all have been a good group. Thanks, everyone.