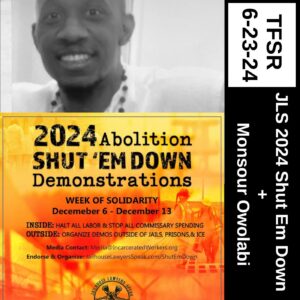

Shut ‘Em Down 2024 + Monsour Owolabi

An interview with Courtney of the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee & Millions For Prisoners New Mexico and Roc, communications bridge for Jailhouse Lawyers Speak and residential manager at the JLS housing center to speak about the JLS call for Shut ‘Em Down strikes inside and outside of prisons in December of 2024. We talk about abolitionism, the organizing that JLS is doing including that transitional housing project and other topics. You can find a past interview with Courtney here.

- Transcript

- PDF (Unimposed)

- Zine (Imposed PDF)

Then, you’ll hear Monsour Owolabi, incarcerated New African political prisoner in the Ferguson Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice system sharing some perspectives on inside-outside collaboration, the role of isolation in prisons as counter-insurgency and the importance of transitional housing projects. Monsour has been involved in Prison Lives Matter, the website https://www.texasletters.org/ has published his writings, and supporters have an instagram @FreeMonsourOwolabi

By putting these segments together, we are not proposing any organizational overlap between Mr Owolabi and JLS.

Shout out to Marylin’s Children for inspirational praxis.

. … . ..

Featured Track:

- Remember Rockefeller at Attica by Charles Mingus from Changes One

Shut Em Down Transcription:

Courtney: My name is Courtney. I go by she/her pronouns. I’m with Millions for Prisoners New Mexico as well as the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee.

Roc: Hi, my name is Roc. I’m currently serving as the JLS communications bridge, as well as the residential manager at the JLS Housing Center. I have a long history of serving at the side of my late great Godfather Dr. Mutulu Shakur, rest in power. My pronouns are she/her.

TFSR: That’s awesome. Thanks a lot both of you for being here in this conversation and much respect to Dr. Shakur. His losses felt for sure.

We’re here to speak about the call by Jailhouse Lawyers Speak for a prison strike in December from the 6th to the 13th of 2024. Because we’re playing over the radio, and also someone might just be coming across this conversation for the first time, they may not be familiar with Jailhouse Lawyer Speak as a formation or even the concept of jailhouse lawyering. Could you all talk a bit about that formation, about its aims, programs, and activities?

Roc: Yeah, sure. So Jailhouse Lawyer Speak is a collective of imprisoned individuals, arguably the largest prisoner-led collective in the US, fighting for prisoners’ human rights, human rights as a whole, and standing firm on prison abolition. Members make up autonomous collectives in the states across the country, and they have all independently studied law and have championed civil rights and human rights causes. I can say that their aim being to challenge the injustices in the judicial system and push for abolition in a process that you hear them refer to as “dismantling the prison industrial slave complex.”

To the other part, being a jailhouse lawyer refers to the practice of people in prison providing legal assistance for themselves and/or others who are also imprisoned. They organize actions and programs inside such as legal research, filing grievances, and advocating for policy changes both inside and outside prison walls. They do a large number of things simultaneously to advocate for themselves and other prisoners.

Jailhouse Lawyers Speak pushes a number of issues, again, such as prison conditions, mass incarceration, the 13th Amendment, and all things aligned with abolition, as well as holding direct action demos, like the 2021 Shut ‘Em Down demonstrations and the upcoming 2024 demonstrations. JLS also has various initiatives and seasonal projects such as the paralegal program, the International Law Project, the Seasonal Joy Project, and they have a bunch of JLS committees, like the political prisoners freedom committee. At the forefront of their projects right now is the JLS Housing Center. You can go to JLSHousingCenter.com and take a deeper look into the Housing Center that they’ve opened up for women activists and women jailhouse lawyers that are being released and need housing, vital documents, and a lot more. You can go to JLSHousingCenter.com to see about that project that they’re pushing out right now.

TFSR: That’s awesome. That’s a lot. With your position as a bridge, like a communications bridge for JLS, can you talk a little bit about the inside/outside organizing? Because there are obviously people on the outside who are coordinating with, standing in solidarity, and amplifying the voices. The role of leadership of people on the inside or recently out of incarceration directing the actions and the strategies and tactics of JLS.

Roc: Yeah, sure. So I guess it’s important to note that there’s a number of journalist liaisons on the outside that helped facilitate different calls to actions. For me, a lot of my work is to sit in on some of the notes that are taken after the JLS Central Committee meetings. I guess the most important thing is that my job is not to interpret what they’re saying, but to literally just be the vessel of what they’re saying to the outside. A lot of their messages and what they’re doing can be seen on their social media accounts, which is all inside-driven.

So I facilitate a lot of the communication between the different outside organizations, for example Courtney with IWOC and some of the other ones. And I’ll take the messages that I get from the Central Committee of Jailhouse Lawyers Speak and facilitate and communicate that with the outside organizations that I know that they’ve trusted and worked with over a long period of time.

TFSR: Aa a follow up, to get a little bit more on the Housing Center, I know that you directed listeners to the website for it. That’s big, providing post-release housing for formerly incarcerated people. Could you talk about just that in and of itself. People obviously can do as they want when they get released. They have life to deal with, they’ve got relationships to figure out, they’ve got surviving under white supremacist capitalism, but I imagine this as providing an opportunity for not only stability to folks that are going to be destabilized when they’re released, but also continuing to allow people place to plug into movement work and have a continuity—I keep coming back to that word—a continuity of the activism that they were engaged with on the inside. Can you talk a little bit about what the role of the Housing Center is?

Roc: Oh, yeah, absolutely. It’s like a massive project. We had this idea of providing housing for people being released, women specifically, for the first JLS Housing Center. The concept of it is incredible. But then when you start to apply, and your hands on… you’re like, “Whoa!” There’s so many arms and legs to this thing. I’m proud to say that we’ve been able to tackle head on. And it’s been about three years now from just the ideation process to actually housing people now. So what started as the idea of providing housing, safe housing.

I think so many of the traditional re-entry homes, sometimes they lack a sense of peace of mind because you’re released after X amount of years, and you’re thrown back into the hustle and bustle of everyday life. Just the simple things like obtaining your birth certificate, social security card, and your vital records, that in and of itself tends to be a huge obstacle for people. To be able to get that done within a matter of days. Then to secure a job or, or whatever it is that you need to do in order to kind of come back into the community and start providing for yourself and or your family.

So that was the first part, just secure a safe home that had a sense of peace. So we’re more remote, it’s more rural. We chose to kind of go further out than in the urban population, which makes sense to be more in a metropolitan urban place, because you have more access to public transportation and jobs and that sort of thing, but you miss that peace of mind, and that’s really what we were striving for.

Then the second part, which is the biggest part, is to absolutely connect them with organizations on the outside who are active and organizing, because the residence that we take on one of the requirements is for them to have a history of activism and/or being jailhouse lawyers, so some form of giving back and helping the cause and the movement. That’s one of the requirements for our non-traditional Housing Center. So just those two pieces alone have been have been massive for us to sort of piece together and make sure that there’s a strong foundation and they can be connected with people like Courtney and IWOC and a lot of other organizations as well, because JLS really wants to continue to fuel the movement and the momentum as it comes in waves. There’s just so much that the people coming out of prison can offer, and they have so much energy and they’re ready to hit the ground running.

We want to make sure that we have a safe place for them to sleep at night, then the essentials, food, water, the resources that we need in order to be okay on a day-to-day basis, then also helping filter them into a lot of the orgs out here who are active. Then on the back end of that, a lot of people don’t see is what it took in order to obtain this home. We spent months actually searching for a house that would accommodate what we were looking for, which was some land, enough rooms where we’re not just stacking people on top of each other but it’s actually like a home. We’ve done huge improvements and renovations, new roofs and flooring and painting and appliances. I can go on and on and on. In the last two to three years, we’ve done more than I think what the average like homeowner would do to their home within like a 5-10 year span. So that’s just sort of a snapshot into the Housing Center right now.

TFSR: Yeah, and just to also mention that it’s notable that it’s specifically a women’s facility. It feels to me that a lot of conversations in the US around incarceration focus on people in men’s facilities, whether they identify as men or not. Numbers-wise that’s a much larger part of the prison population. However, people going into women’s facilities have been increasing at a sharper rate than any other proportion, particularly Black women, over the last decade. So it’s really great to see that JLS is making this investment in something that it feels, at times, movements that are focused on prisons don’t really speak about this part of the population. Does that make sense?

Roc: Yeah, absolutely. That definitely makes sense. I know JLS, at one point, was really hoping to grow their membership in the women’s prisons. As they build on that, and that’s taking more time, this is a great way for them to also support women in the movement as a whole as well.

TFSR: Courtney you have been on the show before a couple of years back talking about Millions for Prisoners New Mexico and also IWOC. And for any listeners that don’t know about IWOC, it’s been around for a while, but if you could talk about the group and the model, both at a local level as well as, because you’re one of the media spokespeople, at a national level, how it coordinates.

Courtney: So we at the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee are prisoner-led, and we’re a section of the Industrial Workers of the World, which is a labor union. Our struggles are very much intertwined in abolition and the end to prison slavery, along with bringing in and looping in allies, community members from the outside, and again amplifying the voices of people who are most proximal to state violence and the human rights abuses that are going on in prisons and jails all over the so-called United States and throughout the world. We do recognize that we are on occupied territories that were occupied through colonization and white supremacy, and that the prison industrial complex is a direct reflection of those systems.

We have members inside. We have members outside. We welcome community members who have been impacted by state violence whose communities have been restructured because of police violence, because of the extraction of our communities into prisons and jails to be used as a source of labor, to be abused, to be traumatized for the rest of their lives. It impacts us generationally. A lot of our communities have been impacted by State violence, and we’re seeing it amp up of course.

So it is a prisoner-led section of the IWW. We understand that it’s going to take a mass movement inside and out to abolish prison slavery. We have folks that are earning anywhere from nothing to pennies on the dollar to perform labor in conditions that are not being regulated, that are not being seen. A lot of what happens in prisons is behind closed doors, behind concrete walls, and the people who are most proximal to it are the most important voices to lift up, and their families.

They are on the frontlines of wage slavery and forced slave labor. Refusal to work when you’re in prison results in retaliation. It can result in being exposed to solitary confinement, and it’s just part of the mechanism of exploitation. The Industrial Workers of the World union has consciously grasped the importance of organizing people who are in prison so they can directly challenge prison slavery, the conditions that they face, and the system itself so that they can break the cycles of criminalization, exploitation, State sponsored divisions of our working class. The prison environment and culture itself is a melting pot of capitalistic and exploitative tactics and all forms of oppression.

We challenge these poisons in prisons, institutions, and we’re trying to build working class solidarity, and I will talk about why that’s important. I also wanted to cover that Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee has a national structure, but there’s also local structures, where locals can form IWOC chapters where they can approach local struggles. But we do stand together as a national unit and try to help each other through our struggles. Each State is different, each group’s struggles are different, so we try to support and uplift whether our folks are trying to fight for legislative moves trying to improve people’s lives in the moment, even though the ultimate goal is abolition of these systems so that we don’t have to see the future of these systems existing because they have caused so much harm to our people. But also having a national structure and other organizations, other autonomous actors, people who are wanting to dismantle oppression, it’s all-inclusive.

I did want to touch on why working class solidarity is so important in abolition and how it intertwines with the struggles to support Palestinian Liberation. Right now we’re seeing the Supreme Court set to make a decision on the Grants Pass v Johnson case this summer. This is coming up. We’re seeing increased criminalization of our unhoused communities locally all over the country. The decision is promising to warehouse and exploit our most vulnerable community members who are even more at risk of brutalization by police. Their voices are unheard and unseen. We’re prepared to see even more of a chokehold on human rights with the criminalization of our unhoused community members, so many who are struggling with a lot of things. We’re seeing struggles with bodily autonomy being criminalized. Queer, and trans people are being criminalized, having to flee from states where their existence is under attack.

Of course, meanwhile, the working class is in a chokehold with economic opportunities dwindling. We’re seeing mass layoffs, automation of jobs with the use of AI. I’m seeing this at my day job just basic entry level work that I do, trying to be squeezed out from my workplace. The value of college education is falling exponentially. So many folks are getting nothing but debt. So many folks like myself, trying to raise up from poverty, get nothing but debt. We’re even more poor. The cost of rent basic necessities, it’s skyRoceting. Gentrification is displacing entire communities and people while our communities are being funneled into the prison system, and this is causing the unhoused population to explode.

The state is obviously gearing up for confrontations with civilians in multimillion dollar cop cities such as the facility in Atlanta in the Weelaunee Forest which was a repurposed prison farm that was abandoned in 1995. We’re already seeing more militarization of police with State violence spilling into universities all over the country and all over the world. System-impacted communities were born and raised with heavy police presence anyway. State violence is a part of our life. It’s a part of the air we breathe. And it’s part of what our parents and grandparents experienced.

Indigenous Black and brown folks have endured the legacy of colonization and slavery for generation after generation. Police and prisons, we know, were built as part of the legacy of slavery and the exploitation of labor of warehoused community members who are violently snatched up off the streets, killed, or just taken in. These very institutions are dilapidated, understaffed, and they’re the source of countless violations to basic human rights under the United Nations Mandela Principles. It’s the source of lifelong generational trauma that our communities have been absorbing.

When you see this state violence spilling over into institutions of higher learning, we saw it in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Here at the University of New Mexico, 11 People were bayonetted when the National Guard was called in. So we’re seeing this on a massive scale in broad daylight all over the place in the so-called US captured from so many angles, because now as a society, we all have technology. We’re all equipped with tools to record and document the abuse by the State. We’re seeing a clear indication that we’re continuing to slip into fascism.

The State is deciding to use force on young people speaking out on genocide, because the State is determined to fund that genocide, and it is going to move forward with it no matter what. The State-sponsored media is the arm of the State, and it’s going to tow that line. University students all over the world are rising to the occasion to stand their ground to demand that schools disclose and divest from genocide. Palestine is the world’s largest open air jail. It’s home to 1.8 million people, two-thirds of whom are under 25 years old. This Monday reach a death toll of 35,091, including 15,103 children and 9,961 women. It’s our duty to stand with students who are demanding an end to the atrocities being livestreamed for all eyes to see.

I also saw that, according to the Associated Press, nearly 2,900 people have been arrested at 57 colleges and universities. Now that students have had the chance to have a glimpse into the conditions that are going on in US jails, this is a time for them to share their experiences, to record those experiences in your mind. 2,900 glimpses, so far, into the struggle facing system-impacted folks. Just a glimpse, but it’s there.

Some people spend their entire lifetimes. Entire families spend lifetime after lifetime without the opportunity for freedom, without the opportunity for adequate sunlight, nutritious food, compassion, any shred of basic human rights, sitting in a concrete cage. I’ve been seeing jail support efforts by community both here in Tiwa territories here in so-called Albuquerque, New Mexico, and that kind of mutual aid I feel needs to spread unhindered for all of our comrades that are impacted, all of our people, all of our communities that are impacted. I want to see this grow.

The solidarity with our comrades behind the wall who risked everything to stand up and fight against oppression and State repression and violence, this is where that solidarity stands. The State has been very busy gearing up for civil uprisings. They’ve put enormous budget creating these cops cities such as the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center. And all but three states we have these types of centers. The major increase in activity started after the uprisings of 2020. According to The Guardian, the student-led uprisings at Emory University are actually also demanding disclosure and divestment from Israel. In addition, they’re also calling for disclosure and divestment from the $109 million facility in Atlanta. Atlanta police trained in Israel with the IDF, and the tactics of oppression used on Palestinian relatives are being used in our communities. We see tanks, we see all of that, militarized police all over the place.

According to IsYourLifeBetter.net, the cost for 55 of the 69 projects confirmed of these cops cities range around a million dollars to $415 million and range in size with larger facilities including 366,000 square feet on 146 acres of land to a proposed site that’s 800 acres. These are cities in which they are using militarized police to practice mass arrests, mass confrontations with the people, because things are crumbling.

This should all solidify the solidarity among working class, our families and communities behind enemy lines in prisons and jails, unhoused folks, all marginalized identities. Our struggles are intertwined with the struggles of our Palestinian relatives. Our fights, our victories, our future are also intertwined. This is where we stand. We do deserve better. I just wanted to lift how these struggles all intertwine, how we can build mass movements by realizing that we must stand with one another. Mutual aid, community care, we take care of one another, we protect one another. We don’t need these systems. Abolition is absolutely possible, and it is absolutely our future. That’s what I wanted to say.

TFSR: Over the last decade, formations like JLS have worked and have played a part, helped coordinate and organize prisoners strikes across facilities that have been backed by outside solidarity. These inside strikes have included work stoppages, commissary boycotts, and the outside solidarity has included contracting officials, talking in the media, showing up at places of incarceration or the sites of contractors who profit off of the prison industries. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about mass incarceration and what governments and companies that are profiting from it.

Courtney: The profiteering, we know that the incarcerated people are legally slaves as per the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. People behind the walls are legally slaves. Billions are made annually off the backs of people who are behind the walls. The privatized services like health care, food, phone calls, they’re outrageously priced. Access to mail is outrageously priced. People have to pay for everything that they have at a very inflated rate. The government spends as much as an elite college tuition per person to keep each person incarcerated, but it doesn’t make community safer. It doesn’t reduce crime.

People are paid pennies on an hour, pennies on the dollar, or sometimes nothing. People were, during the pandemic, performing essential work needed to help run the prisons, mopping up blood from State violence that was enacted on maybe somebody in a cell close to them. It’s contracting with private corporations, some are working in clothing, textile, call centers, everything that you can think of.

We constantly are working with folks to research, members of the academic world try to contribute to researching the connections. But it is big business. Keeping people in prisons is profitable, and all of the beds must stay full. Even if people are just warehoused and they don’t have the opportunity to actually work “prison jobs,” if it’s not the site for that, which is kind of what the situation is in New Mexico. We do a lot of warehousing in remote areas. It still stands to profit.

There’s really no minimum wage that people can make, few safety regulations. Up to 80% of wages can be withheld by prison officials. As workers, people who are incarcerated should be guaranteed the same protections and wages as other workers. It would economically change the situation from being as extractive as it is from families and communities. Ultimately, we want to abolish prison slavery. We don’t feel like any of it corrects anything. It’s entirely exploitive.

Roc: Piggybacking off of everything that was said, I also wanted to note that when boycotting commissary and the prison labor for people on the inside to just having an act of rebellious behavior, people in prison are saying they won’t be pacified by commissary, and it being a small symbolic gesture that that recognizes the objective for companies to exploit people in prison and their families on the outside for money.

I just wanted to also list a few of the big businesses that a lot of people are familiar with that supports prison labor. A lot of the ones that we know of are Victoria’s Secret, Walmart, McDonald’s, JC Penney’s, which I think a lot of them have shut down, but these are just a few examples that highlight the widespread use of prison labor. So I know that JLS is working on kind of putting together like a mass list for people to become more aware and conscious of these big corporations that use prison labor as well.

TFSR: As has been mentioned, JLS has helped to coordinate past strikes, along with other formations in the US. Oftentimes, these have been called for the time around Black August, the assassination of George Jackson and the anniversary of the Attica uprising. So the new one is in mid-December. I wonder if y’all could talk about the significance of the dates for this year strikes. Is it scheduled somehow in relation to the national election season and avoiding that or something else?

Courtney: This year’s Shut ‘Em Down demo from December 6th through December 13th 2024 is a call to action against mass imprisonment and all the profiteering that comes along with it. The Shut ‘Em Down dates are set such to avoid the national election season because the election season often co-opts social justice movements and takes eyes away from what really needs to be uplifted, which is the abolition of exploitative practices in the prison in jail system, as well as the abolition of the entire system in itself.

TFSR: In recent years, some abolitionists have expressed concerns that the focus around organizing on the 13th Amendment and its State level equivalent equivalent sets kind of a low non-abolitionist horizon, which is ironic in some ways. But the work being done by that idea is that the State in the creation of the 13th Amendment simply redefined circumstances to allow for the incarceration, the control, the extraction of labor, and the social death of many of the same portions of the population inside of its borders as prior to the abolition of slavery when there was a systematized method of doing those same things. So I wonder if you all could talk about what you know about that debate around the 13th Amendment as a focus of the strike and if there’s validity to that, if that maybe sets a good measure of people just being attentive of recuperation or the way that politicians will co-opt struggles and rename something slavery, rename it prison, rename it Jim Crow or Black Codes. Did that make sense?

Roc: Sure. So this was one of the things that I think is important that we amplify the voices of Jailhouse Lawyer Speak members. So when talking to them before our interview, they wanted to send a statement in the debate about the 13th amendment. So what they sent was regarding the 13th Amendment debate in our movement, legalized slavery has always been a focus of slavery abolition, and how slavery abolition makes up the foundation of abolition, and JLS acknowledges the concerns of some abolitionists. While some focus on the amendment’s loopholes that allow forced labor, others see it as a tactical target to dismantle the prison industrial slave complex. JLS embraces diverse perspectives within the network entirely.

TFSR: Cool, that’s great. Thank you.

Sundiata Jawanza is an incarcerated New Afrikan abolitionist and human rights activist in South Carolina who’s been publicly affiliated with Jailhouse Lawyers Speak has faced repression and was denied an attempt at parole last year. Are there any other JLS affiliates with support campaigns that we can speak about, Or do you have anything to say about Mr. Jawanza’s struggle?

Roc: Right now, there are not other public campaigns to support. It’s important to note that political prisoner Sundiata Jawanza has gone public after being identified by State agents as an inside organizer. Like you said, he faces repression and has been denied parole due to his national organizing efforts. Right now, due to his concern, and in primary focus on being released, he’s not currently organizing. However, with that said, we absolutely urge people to support Sundiata’s freedom campaign, and you can actually find ways to support and join his fight for freedom by going to SundiataJawanza.com, as well as JerichoMovement.com

TFSR: Again, getting back to the call for the strike, can you talk about some of the ways that listeners can get involved to educate, agitate, and organize on the outside to support folks on the inside for this?

Courtney: So to get involved with the Shut ‘Em Down demonstrations, listeners can educate themselves about the 13th and the prison industrial slave complex, agitate by organizing solidarity events and actions outside prisons and jails, organize by spreading the word and supporting prisoners facing repression, be on the lookout for and support JLS activities during the demonstrations and during Black August, because that still is something that we uplift, and visit the Shut ‘Em Down website for specific instructions.

We also ask that you amplify your support and solidarity to protect folks that are on the frontlines. We know that past actions have seen repression from authorities, including lockdowns, retaliation, loss of privileges, such as reaching out to family, against folks who are participating. It’s really important that all eyes be directed to prisons and jails across the so-called US. That is also very important. Spreading the word, sharing info through trusted networks, phone calls with folks on the inside, newsletters, getting inside, kiosk messaging, secure apps and social media, encourage everyone you know to spread the word and follow JLS and IWOC for any updates and ways to get involved.

We just want to let people know as well that our struggle is not about prison reform. It’s about abolition. We seek to dismantle the systems of oppression and build a better society for everyone. The people will rise up against colonialism and its legacy of white supremacy culture. I feel that our communities are resilient, ready to fight with every breath that we take for a world without police in prisons, where our needs are met, where we aren’t exploited for our labor and robbed of our meaning and lives. We do deserve a better world, and we will build this up. Our folks and comrades who are risking everything, they deserve to have our support and for us to have our eyes on their struggles and work to amplify their struggles.

Roc: I also wanted to touch a little bit on the 13th Amendment and sort of the setting a low horizon. So when it comes to the Shut ‘Em Down demonstrations, it’s great to think about it as sort of the overarching platform for abolition as a whole. So, whether you’re pinpointing specific issues like the 13th Amendment or prison conditions, or you’re one of those people who just want to take a wrecking ball and knock the whole thing down, the Shut ‘Em Down demos opens up a place for abolitionists as a whole to come out and really amplify whatever causes that are aligned and tied in with abolition.

I just kind of wanted to make that clear too, that although you will see a lot of boycotting commissary and 13th Amendment stuff within the Shut ‘Em Down demos, it’s really a collective of a whole. I think that’s what JLS was wanting to solidify when they say that they’re embracing their diverse perspectives within their network, because if you think about it, it’s this massive machine and our job is to deconstruct and destroy it. Dismantling the prison industrial slave complex, to take it down you can either hit it with a wrecking ball for immediate impact or you can meticulously deconstruct it piece by piece by focusing on the 13th amendment or the different pipelines. Maybe the most effective approach involves both methods simultaneously. I think that’s also an important message too. That it’s not just one or the other, but for everybody collectively to ensure a comprehensive and lasting transformation.

TFSR: Just getting rid of the building doesn’t get rid of the relationship that is incarceration in its specific form in this country.

Circling back to the question about communication, obviously JLS has its communication and lots of comrades who aren’t JLS are still going to be forwarding that call behind bars. A lot of communication happens through illicit means, and that’s how people can avoid administrations knowing about all the plans. But when we’re communicating with folks behind bars, the letters are getting scanned, they’re getting searched for keywords, audio can be recorded from phone calls and can be searched for keywords, even visits. Would you all mind saying a thing about what is a safe approach to having a conversation with someone who’s incarcerated in a way where it’s not going to inadvertently get them put onto some sort of watchlist just because you decide that you want to raise information about this thing that other people are doing? Is there a safe way to do it?

Roc: That’s a great question. I have JLS on this message thing right now. So I just posed that to them. So it’ll probably take just a few seconds for them to get back if they have specifics. … Okay, so coming from the inside, they’re saying that there really is no foolproof safe way other than person-to-person visits, that sort of thing, which is why I guess it’s so important, again, for us on the outside to share as much as we can. They say, just pass the info along as best as you can to your contacts on the inside.

TFSR: Yeah, that makes sense. People find really, really ingenious ways of getting information between the bars. What is the movement without imagination?

That’s the questions that I had. You’ve already named some websites, but any social media accounts or websites that specifically people should be paying attention to in the build up and who they can communicate with if they want to share their actions moving forward?

Courtney: Yeah, so we just wanted to share that our website is IncarceratedWorkers.org You can also follow our Instagram @IncarceratedWorkers.

Roc: People can follow Jailhouse Lawyer Speak on Twitter @JailLawSpeak. They can also follow them on Instagram @jailhouse_lawyers_speak. Again, they can also go to JailhouseLawyerSpeak.com. From there, there’s links to the JLS Housing Center, which would be JLSHousingCenter.com if they wanted to go directly there. For Sundiata Jawanza’s freedom campaign, they can go to SundiataJawanza.com. They can also go to the JerichoMovement.com. They’re supporting his freedom campaign as well under their political prisoners.

TFSR: Yeah, Roc and Courtney, thank you so much for this conversation. Were there any parting words that you wanted to say, anything that I forgot to ask about that you want the listeners to hear?

Courtney: Yeah, you know, I did, actually. There’s been a quote that’s been running through my mind as I’ve been seeing year after year we’ve been descending into fascism, and it is a quote by Assata Shakur: “It is our duty to fight for our freedom. It is our duty to win. We must love each other and support each other. We have nothing to lose but our chains.” That’s all.

Roc: I’ll just read a quick excerpt from Jailhouse Lawyers Speak who says, “Remember our struggle is not about prison reform, but abolition. We seek to dismantle the systems of oppression and build a more just society for all,” and to thank everybody for listening and supporting their ongoing causes.

TFSR: Awesome and thank you to them for engaging, and thank you to both of you for being a part of this conversation. Much appreciated.

Roc: Thank you.

Courtney: Thank you.

. … . ..

Monsour Owolabi Transcription

Monsour: This is Monsour Owolabi, a New Afrikan political prisoner currently confined in Texas for life without parole. A little bit about myself, to introduce myself… I came into radical politics generally being exposed to racism and systematic oppression, national oppression, etc, as a child growing up in Texas. Actually, I would say I came full circle in a more complete awareness of radical politics and organizing through the constant “in your face” racism and oppression that comes with the territory of prison, right? So, my analysis of things was derived from being at the lowest of the lowest part of the prison population. I’ve been locked up now for 14 years, and I’ve spent most of that time, about a decade or so, in solitary confinement, at the worst levels of solitary confinement you can be on. And it just so happened that I was in one of the most racist prison regimes in the state of Texas, right? And so everywhere from the lot of the prisoners to the officers and administrators were in cahoots. You know, you become a little bit aware growing up about the racial components of the country, but it’s different when it’s in your face all day, every day, and you’re the target of it. And so that alone, being around some good people, who grabbed me and took hold of me, man, and took the time to give me good books and educate me, that kind of brought me into the fold, more or less. And then, as I began to actually clash with The State trying, like most people, simply to get humane treatment, simply to have international human rights recognized. And with The State doing what it’s supposed to do in its role, [going] as far as preventing that from happening, that only upped the ante as far as my level of radicalization and politicization [goes]. I think as you organize, even the most successful organizing against The State, usually, in most cases, simply increases one’s radicalization. So that’s a little bit about me.

As far as what I have going on right now, several things, but I’m currently in the midst of a state-wide fight, inside and out, to try to tear down the walls of solitary confinement. As I see it, solitary confinement is the political tool in the hands of The State. Number one it’s the ultimate sense of what behavior modification tools are like. What usually happens is you get these influential prisoners, the most influential, and they throw them in these cells, and they isolate them in absolutely inhumane conditions. You know, Texas, one of the things its known for Texas is it’s heat and humidity, right? So they throw [influential prisoners] in these cells all of this Texas heat, and they lock them away. There’s no air conditioning, there’s no good source of water supply. You know what I mean, even the water is contaminated here where I’m at, the Ferguson unit, ok? People are getting sick. I’ve been sick multiple times, throwing up, viruses, etc from the contamination of the water. I don’t want to go on and on about that, but that is the condition. So you spend years and years and decades [in those conditions]. And the majority of these people, the best of our leaders, spend years and decades and some of them even die in these conditions, and it’s perpetuated because of these conditions. This is a tactic used to counter insurgency and [to introduce] behavior modification.

So, although not everyone within a united front against solitary confinement in Texas and otherwise is as radicalized, politicized revolutionary as myself and others, I feel that we as radicals, by various stripes, have to not only join in the fight against solitary confinement, but try to hold the leading influence in it. A lot of times we pick and choose the struggles we want to jump in, and that’s cool, we have to do that to a degree, but sometimes we have to jump into things head first. Because at the end of the day, it’s the class struggle. And the class struggle spreads itself through the movement of the people. So the movement against solitary confinement is a grassroots movement, at least it has expressed itself in Texas. So you got a bunch of “normal” people (I mean, we are normal, but you know what I mean, “normal” people), they see this outrage, and it’s a moral thing for them. So with us being who we are, it’s a moral thing, but it’s more so we see it as a political thing as well, right? And so we have to bring that analysis to the people, also struggle for a big chunk of the influence on the direction of the movement. If not, what usually happens is you have what’s called an elite capture. Elite, the people who have access to resources, education, and all these different things: consciously or unconsciously tend to steer the wheel of the various movements. And what happens is that, almost invariably [they] water down the goals and aspirations of the grassroots movement. So in order to prevent that, we have to ingratiate ourselves with grassroots movements and see to it that those grassroots aspirations are being followed through. So that’s something that I’m doing right now. I encourage people to check out texasletters.org for some of my writings on the subject. Currently [there is] a book release tour all around the state of Texas. We just had the launch this past Sunday, May 19th. That’s going pretty good. And people are coming out, getting these books, being educated on the issue of solitary confinement in Texas as well as oppression inside Texas prisons, more generally. And they’re coming in to these events and getting workshops going on, being educated by different sectors within the movement. And so that’s something I’m doing now.

Also, I’ve been permitted to include something that I was trying to get off the ground right now, trying to galvanize people around the country various stripes. We’re looking to set up a working group to bring the, like Malcolm X and others promoted, to talk about bringing the issues of the people to the international community. And we frequently lament our opposition to the enemy State. However we get caught in this routine, it’s almost as if we’re dependent upon them for the different resolutions and solutions that we need. A lot of that is not necessarily our problem, it speaks to our level of dependency and things like that in the state of neocolonialism that goes on within the Empire. To get out of that bag, we have to get together and I think it’s not just the prison movement, because the lines are more blurred, as far as different barriers and things, I think that we can be at the forefront of taking international petition complaints to different international bodies. Expressing US refusal to recognize international human rights and international treaties, and even more so than refusing to recognize them, they’ve gone out of their way to create a safety net (for lack of a better word) to prevent them from being liable to respond to these treaties that they’ve signed. So ultimately, they’re acting as watchdogs to other nations and people without liability in the same international treaty organizations and committees. I want to educate the general public more about that. I can’t do all that in this one little sitting, but to educate the general public about that, as well as the prison movement as a whole, I think would politically help galvanize us.

I’m a person who likes to learn a lot and knock down the walls between ideology, between ethnic groups, nationality, sexuality, religion, etc. I feel that the prison movement can be a step forward in that [direction]. I believe that there are relevant things that people on the outside can do to impact the things, to support the prison movement. The prison movement is international, it’s national, but it’s also very hyper-local. And what I mean by that is because of the setup of the Empire, each state really, even each prison and jail itself is at a different stage of development as far as movement [goes]. In some cases [there is] no movement at all, in some places the movement is on a high level. So we have to begin to understand that. Because that is what it is, we have to be able to tap into people like yourself, who have been doing this prison support work out there for years. Because of the years and decades in the struggle, you would have more contacts on the inside than the average person.

So it all begins with the contacts on the inside and not just any contacts, but contacts that have a track record of being active. Because sometimes people have a name and reputation, but their activity is not frequent. We need people that are active and involved. Those people at the local level can be able to tell people more or less what they need. But to give a better answer, in less general terms, I would say a lot of things start with helping people transition to the outside.

John: Yeah, and that’s been a real struggle. That can be a real struggle sometimes.

Monsour: Exactly. So if I had my wish, I would say that. You know how the bourgeois prison reformers, they get these different grants and things like that and put them [money] into transitional housing. I applaud the move, but it would be better if our comrades did things like that were able to put together even just a nominal version, a novel version of a construct like that: the transitional housing for particularly politicized in the business.

John: Absolutely, yeah. And put that way it helps them stay involved in the movement when they get out…

Monsour: That’s the whole purpose. And that goes towards setting up welcoming communities. Because these are two things happening. Number one, the politicized prisoner is a minority within the prison system anyway. So, you get out now and you become basically a minority inside of an even bigger minority in the free world. And maybe you know some people that are into the reform movement and things like that, maybe you might go that direction. But nine times out of ten, what happens is you fall into either regular [life]: getting a job and going to school, you get caught up in the ways of bourgeois life. Or you just fall off the wagon, and you are on the fast track back to confinement. And to stop that you have to set up welcoming revolutionary communities. And it starts from maybe putting some resources into that, a revolutionary transitional housing that’s a good idea to work towards in the future. Also for those on the inside, because sadly, at least in my experience, the majority of political and politicized prisoners have a lot of time. So if nothing’s done, they’ll stay, and we’re those people… I have a life without parole, so we will be here.

So part of support for these particular individuals, starts with maintaining constant communication with these individuals because life in prison is shaky, it’s monotone, it’s the same thing every day, but at the same time, things change suddenly. But it starts there. You have to be in a position to be willing to number one provide education opportunities. I believe the most deeply rooted thing that political prisoners can do on the inside is politically educate the people around them, change the prison culture around them, and build up solid disciplined revolutionaries that’ll be able to come out and act as influencers in the outside movement. Because they have a certain level of discipline, a certain level of experience, and a pedigree that they’ve garnered during their time on the inside. And that has to be ignited and engineered by people like myself on the inside. So a person like you on the outside, and you more or less do this through the initiative that you’ve got going on, But for others [a goal would be to] engineer and make it easier for the political prisoners, provide them the truth that leads them to do their job. And people like us are completing our job by having a consensus on where our attention needs to be. It’s not always about issue-oriented organizing work. Sometimes we need to bust it down, sit in and build up collectives right here. Let’s just put our heads together, see who’s who, what is what? Who’s willing to sit down and study and struggle session and take six months to a year out and just study, just build up their ideological capacity? And that’s really boring work. It’s not exciting, it’s not sexy but it’s really the most important. Because that is what will carry us through when repression comes down. And people on the outside come in, and those of us on the inside come out. [We need to] make sure we have a steady rotation of people that’s always holding our position in high esteem. Because, like I said, we are a minority, we constantly need human resources before we have any other resources. And we will constantly be isolated by not only The State but also agents of The State within the mass of the people. So for better or worse, consciously or unconsciously, their actions and omissions tend to isolate the more radical of us. But, for better or worse, you just got to keep on pushing man.

John: One thing I wanted to shout out before we stop recording, is that just your initial enthusiasm about us getting these regular writing events is really helpful, and we’ve been distributing, especially a lot of that [text] drawing the connections between Palestine and American prisons that you wrote. So I just want to say on record for people who get to hear this: thank you so much for writing that thing. And we’ll have copies of it on the table [at our event] so people can pick it up. And yeah, if you want to say like one quick thing to everybody who’s gathered because we’re going to play this on Sunday at the event we got. So if you want to do one quick shout-out.

Monsour: I just want to shout-out to everybody for coming out, for taking time, or for even giving a damn, because a lot of people don’t care about what’s going on inside of here. So I would just thank all of you. Appreciate all of you. And free Palestine! From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free! That’s all I want to say.

John: Okay, thanks a lot, dude. Thank you so much for doing this.