Keep Loxicha Free!: A conversation with Bruno Renero-Hannan about Political Imprisonment and Indigenous Resistance in Oaxaca

This week William got the chance to speak to Bruno Renero-Hannan, who is an anarchist historical anthropologist from Mexico City, about their solidarity work around two of the original 250 Loxicha Prisoners in the state of Oaxaca. This rebellion and imprisonment occurred almost simultaneously to the Zapatista rebellion in Chiapas in the mid-late 90s with very different results. We talk about the long and complex history of this case, the similarities and differences between this uprising and that of the Zapatistas, the ongoing political repression of Alvaro Ramirez and Abraham Ramirez, and the economic solidarity push being orgainized by our guest, as well as some stark parallels between this case and that of the remaining 59 J20 defendants. If you would like to see the 45 minute broadcast edit of this interview, you can go to The Final Straw Radio Collection on archive.org.

To contribute to freedom for Alvaro and Abraham, please visit https://patreon.com/KeepLoxichaFree.

As per the very reasonable request on the part of the folks doing support for Alvaro and Abraham, we have omitted the Sean Swain segment for this episode. The You Are the Resistance topic did not pair well with the main interview content nor were Keep Loxicha Free supporters aware of the segment. We regret any confusion or discomfort that this caused.

We would like to take a bit of space here to explain to new listeners that many of the Sean Swain segments are meant in the spirit of satire; Swain himself has been a political prisoner for over 25 years at this point, and his humor is sometimes abrasive, but he is a committed believer in the dismantling of all forms of oppression.

He and we are open to feedback on this segment, and any content we present!

You can reach us at thefinalstrawradio@riseup.net, and he can be reached by writing to:

Sean Swain #243-205

Warren CI

P.O. Box 120

Lebanon, Ohio 45036

Resist Nazis in Tennessee

On Saturday, Feb 17, Matthew Heinbach of the Traditionalist Workers Party will be speaking at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville from 1-4pm. If you don’t like this, you can contact the University by calling 8659749265 and demand that they disinvite this open neo-nazi organizer from their campus!

Some Benefits in Asheville

For the drinkers in Asheville, this week features two libation-centric benefits for books to prisoners projects.

On Wednesday, February 14, Valentines Day, three bars in Asheville will be participating in a drink special that will raise money for Tranzmission Prison Project, our local LGBT books to prisoners project with a national scope. You can visit the Crow & Quill on Lexington, the Lazy Diamond around the corner in Downtown or the Double Crown on Haywood in West Asheville on Wednesday for more details.

On Thursday, February 15th at the Catawba’s South Slope Tasting Room & Brewery (32 Banks Avenue #105) for their first New Beer Thursday fundraiser of 2018!! Starting with the release on the 15th and running through March, a portion of the cost of every glass of their pomegranate sour sold will be donated to the Asheville Prison Books Program!

More events coming up this week include: Thursday the 15th at 7pm Blue Ridge ABC is holding a benefit show at Static Age for a local activists with a sliding scale cost. Bands featured are Kreamy Lectric Santa, Cloudgayzer, Secret Shame, Falcon Mitts & Chris Head

Later that night in Asheville, the monthly benefit dance party called HEX will be holding an event at the Mothlight to raise money and materials for A-Hope, which provides services locally to houseless and poor folks. Bring socks, footwear and camping gear to donate!

On Tuesday, April 20th at 6pm at The Shell Studio, 474 Haywood Rd on the second floor, there will be a showing of the locally produced documentary entitled Hebron about human rights struggles in Palestine.

On Friday the 23rd at 6:30pm, the Steady Collective will be participating in a Harm Reduction forum at the Haywood Street Congregation at 297 Haywood St. in downtown.

Also that night, BRABC will be showing the latest TROUBLE documentary by sub.media at 7:30pm at firestorm books and coffee. This will be a second on Student Organizing around the world.

Finally, on Saturday the 24th 9am to 3pm at Rainbow School, 60 State Street in Asheville there’ll be a Really Really Free Market organized by the Blue Ridge General Defense Committee or GDC. Bring stuff that’s still good to share and come back with other stuff that’s still good for free! Perfect for spring cleaning or dealing with inclement weather on a budget.

A Call for Art Submissions for ACAB2018…

A reminder that if you are the sensitive, artistic type, the ACAB2018, or Asheville Carolina Anarchist Bookfair is soliciting art for fundraising and advertising purposes. If you have image ideas that you can put into action and want to share them, that’d be dope. We’re looking for things we can put onto postcards, t-shirts, posters and other swag to spread word about the event and help us cover the costs of operation. Contact us at acab2018@riseup.net

…and for Yours Truly at TFS

Likewise, if you are feeling artsy fartsy and want to help out this show, we’re looking for swag imagery, either as a logo or a standalone piece of art we can feature for fundraising purposes. If you like the show and want to help, post your files on share.riseup.net and send us a link at thefinalstrawradio@riseup.net or share it with one of our social media identities. If we choose to use your art, we’ll send you a mix tape with one side produced by each of our regular contributing editors.

. … . ..

Transcription

This is the transcript of an hour and a half long interview conducted by The Final Straw radio show, which is a weekly anarchist radio show that hosts interviews about a wide range of topics, including Black liberation, anti racism, anti sexism, LGBTQ solidarity, struggles against extraction industry and pipelines, prisoner solidarity, and solidarity with refugees and migrants, among many other topics. While we do some informal fundraising, this show is a volunteer effort and can be accessed free of charge.

This show has been running for over 8 years, and all the archives can be found at https://thefinalstrawradio.noblogs.org

You can write to the producers at

The Final Straw Radio P.O. Box 6004 Asheville, NC 28816

. … . ..

The Final Straw Radio: (Introduction) This week, I got the chance to speak with Bruno Renero Hanan, who is an anarchist historical anthropologist from Mexico City about their solidarity work around two of the original 250 Loxicha prisoners in the state of Oaxaca. This rebellion and imprisonment occurred almost simultaneously with the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas in the mid to late 90’s with very different results. We talk about the long and complex history of this case, the similarities and differences between this uprising and that of the Zapatistas, the ongoing political repression of Alvaro Ramirez and Abram Ramirez and the economic solidarity push being organized by our guest. As well as some stark parallels between this case and the case of the J20 defendants.

TFSR: Thank you so much for taking the time to come onto the show. Would you tell listeners a little about yourself and talk about what projects you do?

Bruno: Yeah, sure, I’d be happy to. And first of all, thank you for having me on the show. It’s an honor, a pleasure and I really appreciate the space.

My name is Brune Renero Hanan. I am originally from Mexico City where I grew up, although I’ve lived in the United States for quite a while now. And I am from a kind of bi-cultural, bi-national family. So, currently I live in south east Michigan where I am a PHD candidate in Anthropology at the University of Michigan. And the main work I’ve been working on the last 3 years has been, partly through political solidarity and party through my academic research with political prisoners in Oaxaca Mexico. In particular over the last several years I’ve been writing about and working in different capacities to support a group of political prisoners known as the Loxicha prisoners who were all Zapotec men incarcerated for several decades since the 1990’s up until just last year. And that’s mostly what we’ll be talking about today. But, other projects that I’ve been involved in, I’ve also done other forms of politically engaged research in the state of Guerrero around guerrilla movements there in the 1970’s and state terror and the so-called Dirty War of state violence there.

I’ve also done stuff around anarchist organizing in Mexico City, other left political stuff around the Cult of Santa Muerte in Mexico City. I’ve been involved in political organizing to support the families of the families of the 43 disappeared students of Ayotzinapa. For instance we, here comrades and I in 2014, organized a welcome for the caravan of family members when they came through. I’ve also been involved in anarchistic and antifascist organizing in Ann Arbor and in Michigan, working with Huron Valley. Right now, I’ve kind of brought some of that solidarity with political prisoners in Oaxaca into conversation with folks here in Michigan and that’s sort of become a joint project between folks in Oaxaca and here Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti.

As far as resources, the one thing I’d like to plug is our Patreon website. It’s a sort of gofundme sort of thing where people can sign up to make monthly donations which can be anything (as little as $1 each month up to as much as they’d like to. And we’re trying to build up to covering the impossible and unjust court fees being called “damage reparations” which our comrades Abram and Alvaro have to pay each month. So that’s the one thing I would ask people to remember and if they’re able to get on there and donate. So, that website is https://www.patreon.com/keeploxichafree . That Patreon website is what we’re trying to build right now.

And it’s challenging, trying to build it up through folks we know and without having to really go through any questionable or unethical ways of getting money or would compromise this project in any way. It’s sort of going peer to peer, our friends, friend networks, or reaching out in a space like this where people who might also feel solidarity, could join on.

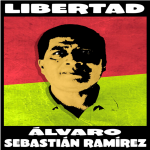

TFSR: And let’s talk about the situation. So, like you mentioned, we’re here to talk about an ongoing situation of political repression against two indigenous, Zapotec men, community members Alvaro Sebastian Ramirez and Abraham Garcia Ramirez who are from the Loxicha region in Oaxaca. They were incarcerated for 20 years, also like you mentioned, for resisting the Mexican state and were just given what is ridiculously called early release. And we’ll talk about that more later. But could you talk about the original struggle in which Alvaro and Abraham got arrested?

Bruno: Definitely. So, this is a slightly complicated story and it’s a long history now. So, we’re talking about the situation of political repression against these two political prisoners, Alvaro & Abraham (no relation between the two of them) and they are both Zapotec community organizers from San Augustin de Loxicha, which is a town in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca, very close to the state of Chiapas which is very well known as being the site of the rebellion of the Zapatistas as you mentioned. Yes, Alvaro and Abraham were longterm political prisoners known as the Loxicha prisoners. They were the last 3 to be released but originally this was a group of upwards of 200 prisoners, all of them Zapotec men, a few women later, but from the original group almost entirely men, arrested between 1996 and the late 90’s.

All of them were accused of being complicit in a guerrilla armed uprising that took place on August 28, 1996, when a guerrilla group called The Popular Revolutionary Army, or EPR, attacked soldiers, police and marines, naval installations in various part of Mexico simultaneously that night, but the most forceful of those simultaneous attacks took place on the coast of Oaxaca near a very fancy tourist resort town in a place called La Cruzecita Juatulco. And there, close to 20 police and soldiers died and several guerrillas died as well in this confrontation. And according to the state and federal authorities, they discovered amongst these dead guerrillas that one of the members was a municipal authority from this town San Augustin de Loxicha, where there happened to be this very strong indigenous movement which had emerged in the early 1980’s and was at this point very strong, fairly radical.

Alvaro and Abram were both members of this movement that was largely organized around this indigenous organization called The Organization of Indigenous Zapotec Pueblos, or Communities, formed in 1984.

So, in 1986 when the guerrillas of the EPR attacked soldiers and police, the state ended up basically pointing their fingers at this entire region, this entire region of Zapotec communities within the fairly large municipality of San Augustin de Loxicha. It basically uses this guerrilla uprising as an alibi to crush this strong indigenous movement that had been growing for the previous ten years in this area. So, there’s various ways to answer this question of why are Alvaro and Abraham in prison, what was this original struggle? Part of that original struggle that landed them in prison was their many years of activism and organizing in the OPIC, the Organization of Indigenous Zapotec Pueblos in and around Loxicha.

Alvaro had also been involved in the democratic teachers struggle of Oaxaca since the early 1980’s. Abraham had also been involved in other leftist organizing prior to that as well. So, that’s one answer: they were political prisoners because they were political subjects who were very active in their communities, forming assemblies, organizing marches, enormous marches, taking over the central plaza of Oaxaca City, in the Zocalo, taking over the airport. That’s part of what makes them political prisoners from 1986 onwards.

The other is that they’re accused of being Guerrilleros, members of a revolutionary, clandestine organization which has often been the classic definition of being political prisoners. However, Alvaro and Abraham weren’t the only ones arrested, as I mentioned. They were 2 out of upwards of over 200 people from this cluster of communities that share the Loxicha Zapotec langauge who were all arrested under these charges of being guerrilla’s, but many of them were not even involved in even the region social movement. Many of them were completely a-political or perhaps might have had a contrary politics.

The point being that in the kind of witch-hunt that took place there in the aftermath of the EPR attacks, people were just rounded up randomly at times. It was really a situation of state terror that happened there in San Augustin de Loxicha from late 1996 with the militarization of that region, with the beginning of the mass arrests that led them to this sort of locally well-known story of the Loxicha prisoners. So, militarization, mass arrest, kind of explosion of paramilitarism, a return of violent executions. In addition to the prisoners, there’s also the situation of executions, disappearances, rape… You know, it’s really a horrific situation that took place that didn’t end up getting a lot of attention for many reasons at the time. It got a little attention, but nothing in comparison for instance to the attention that the Zapatistas got in Chiapas at the time. And partly, that had to do with the complicatied reputation of the EPR, this guerrilla movement that has it’s origins in the late 1960’s and 1970’s in other parts of Mexico, Central Mexico, also kind of through coalitions and alliances through, it’s roots in the state of Guerrero.

Going back to the original question of what was the original conflict then that got Alvaro and Abraham to be long-term political prisoners and at that having just gotten down to 2017, that they were in fact the longest ongoing cases of political imprisonment in Mexico that I know of. I don’t know of any political prisoner in Mexico in the 60’s, 70’s, 80’s that was in for 20 years or even close.

TFSR: Thank you so much for that incredibly detailed answer. Can you talk about just what they were officially charged with by the state? I just remember seeing Alvaro’s statement, his recorded statement on ItsGoingDown.org about “I was charged with this and this and this and this” and it was just this amazing long list of charges.

Bruno: Yeah, definitely I recommend that folks check out that video, it’s like 3 minutes. Especially if you speak Spanish, even though Alvaro’s just reading from his letter, he’s a very charming person. It’s cool to be able to hear his voice. And for me it was special to produce that video and to be able to see it because, having known him for upwards of 6 years now, it was the first that I was able to film him or take a picture of him or use an audio recorder while talking to him. Even though we’ve had this kind of relationship of interviewer, interviewee for half of a decade.

So, in that video he lists all of those charges and it’s kind of ridiculous, this laundry list of every imaginable crime that you could throw at someone, including terrorism, conspiracy, homicide… Basically, every conceivable high-caliber political and violent crime thrown at somebody. To the extent that in the early days when he was first charged, he had a sentence of 190 years. He was a well-known and respected teacher where he was from, kind of a well-respected and radical organizer. And this is why he ended up with those charges. Partly the fact that he was who he was, as someone who was really working to build autonomy in San Augustin de Loxicha, in a model that was similar to what the Zapatistas were doing, not identical, but something similar.

The combination that Alvaro and his comrades were doing that work and the fact that the Mexican state urgently needed scapegoats and the infliction of actual terror in order to clamp down on the uprising of the Popular Revolutionary Army or anything that smelled like it in order to not be dealing with that front as well as the Zapatista front which at this point the state could not simply annihilate or ignore… So, they had to kind of deal and negotiate with it.

The combination of these two situations are what led them to someone like Alvaro having a 190 year sentence. What exactly these were… The most important of these is Omicidio Calificado, which can be translated sort of like 1st Degree Murder. It’s not exactly the same as 1st degree, it can also be translated as Aggravated Murder. That’s the one that ended up adding the most number of years to the sentence as well as attempted homicide. They were kind of pinning the murder of soldiers and police to them, as well as several of the other long-term Loxicha prisoners. In addition to the charges of aggravated homicide and intended homicide, there was also as I mentioned terrorism, conspiracy, stockpiling of weapons, theft, illicit use of foreign property, damage of former property, illegally detaining someone else or impinging on their freedoms… it’s a long mouthful of things which in the end some of those were dropped through appeals, through different legal actions over the 20 years in prison.

Several of them such as terrorism, stockpiling of weapons, were honest symbolic ornaments placed there by the state to make clear what this was about. On the one hand, dismissing these charges as being about criminals and not authentic, political entities that the State should have to negotiate or deal with such as they were with the Zapatistas, but rather to deny that they were political prisoners while placing these very strongly politically tinted and stigmatizing charges onto their sentences such as terrorism, conspiracy, so on. Which were later dropped. So, terrorism, that kind of very particularly stigmatizing and dangerous charge… Being called a terrorist gives states basically a free hand to do whatever they want to people. And that was even before the so-called War On Terror had begun. This was in the 1990’s, sort of the run-up to the logic of this War On Terror, as well as in this sense developing and practicing some of the methods that the State would later use in the so-called War On Drugs. Both as Narcos and as the State.

Yeah, so the charges, I was saying, in the end that Terrorism, an especially flashy one, got dropped I think around 2009 during an appeal, 2010. But, it was notable to me as I was living in Oaxaca, visiting the prisoners regularly, at which point they were transferred from this low-security state prison where some of them had lived/been held captive, this group of the last 7 of them were transferred to a new high security Federal semi-privatized prison 2 hours south of Oaxaca city. I remember that in a statement from the State government explaining why these prisoners were transferred, they would invoke this charge of terrorism even though it had been dropped already. They said something like “The secretary of Internal State Security announced yesterday in a statement that all of the Federal prisoners in the state of Oaxaca being accused of being Narcos as well as the 7 Loxicha prisoners accused of being armed guerrillas and terrorism were all transferred yesterday to the new Federal Prison in Miahuatlan etc etc”.

So, constantly invoking this terrorism charge even though it was dropped years ago and was always useless, but symbolically those things ring out and give the State a lot of power in being able to manipulate people and coerce people or throw them in prison or use violence against them when you accuse them of being a terrorist. Especially when there’s a lot of silence and un-memory, I would call it, around the issue such as there were around Loxicha, where there’s always been a committed solidarity movement around the prisoners since 1996, but it has waxed and waned, kind of in and out of public perception, submerged and then emerging again into awareness locally, sometimes nationally. At times, gotten international attention. Certainly there has been committed International solidarity from anarchists in France, from the CGT in Spain, folks locally in Oaxaca City, in Mexico City. From, sometimes, fairweather solidarity and sometimes really long-term. I think it’s particularly different anarchist groups or anarchist leaning groups in Mexico and Europe who really stuck with Alvaro in particular. On account of his kind of adopting the 6th Declaration of the Lacondon Jungle of the Zapatistas in the last 7 years. That’s something we can talk about…

TFSR: As you were talking I was thinking about this aspect that the state has which is a kind of toxically manipulative… especially with the stigmatizing charges that you were talking about like terrorism, which… I was interviewing somebody some time ago and they said something like “The war on terror is a war on emotion”, which is something that is very very difficult to contain and very difficult to define. And it’s something that, even though the charges were dropped, it’s something that follows folks around forever. Which I think is the nature of the carceral state and will sound very familiar to people who have been keeping even half an eye on political repression cases around the world. And you did answer the question that I had, to some degree, I was going to ask “What have solidarity endeavors been like throughout their incarceration and what kind of media attention have they gotten?” And I was wondering if you had any other words about the fair-weather nature of support for the Loxicha prisoners…

Bruno: You’re absolutely right in seeing that one aspect of what the state does is manipulating and coercing. Particularly in some of it’s most egregious ways through methods or strategy such as War on Terror or War on Drugs. You’d mentioned that someone you had interviewed before had called it a sort of War of Emotion against Ghosts, not that one metaphor has to exclude the other.

But I think that you kind of need the emotion in order to animate the war, to allow it to happen. And in order to have the emotions, you need to have the ghosts and they can be ghosts on illusions of things that are there or things that are made up. And I think that toxicity is also really an important concept when thinking about State violence, especially the most directed State of Exception-y violence really depends on ideological toxicity. It strikes me as relevant to the Loxicha story..

The Loxicha story is, as I’ve come to know it, there’s the pre-96 Loxicha story, which is politically the story of a growth of the Inidgenous Movement. And the second half is the story of a community or cluster of communities dealing with State violence and political stigma that particularly took its most direct form in the formation of this group of people that became known as the Loxicha prisoners. As I mentioned, some of them were highly politicized (even radical) political subjects, organizers, militants. Some of them, who became part of this group of hundreds of political prisoners, were completely non-political or political in ways that you wouldn’t think would get them in prison for being Leftist Insurgents. But many of them, almost all of them were Inidgenous, many of them spoke very little Spanish. That’s partly a manifestation of structural racism and classism in the Mexican political/legal/carceral system. Mexican prisons are full of poor people, indigenous people, innocent people… Not that I think that innocent or non-innocent is a formula that works to put people into cages, I don’t think that you can put people into cages. But this is one of those lines that people in cages, the prisoners themselves would say to me “Prisons are full of poor, full of Indigenous, full of Innocent people.” So, that’s sort of some of their thinking.

So, in any case, you get hundreds of people thrown in there and part of what this focused mass-incarceration of Indigenous people from this one area accomplished was to fracture this political Indigenous movement that had emerged there in the previous ten years. Kind of fractured, and stopped it in its tracks. The State is always good, the Mexican State in particular, at causing infighting, infiltrating social movements and here it really showed its talent at undoing and fracturing a social movement, pitting it’s leaders and members against each other. While at the same time, they were being attacked on all sides. They were confronting militarization, the rise of paramilitarism, the return of caciquismo and pistolerismo, the rule of old political bosses and gunmen which that organization had emerged partly in order to oppose.

What the State needed at this point in 1996 when it was dealing with the Zapatista Uprising in Chiapas, really taking the State by surprise… There was certainly a lot of fear on the part of the State of other Indigenous rebellions or other rebellions of the poor, of other Zapatista movements and uprisings happening in other parts of the country. The State, quite frankly, was terrified of this. So in ‘96 when you get yet another surprising attack, but at this point the Mexican State, the Federal government, had no other choice but to engage with the Zapatistas because they were very successful in what they did. In forming their communities and their rebellions, a revolutionary army. Throughout the 1980’s and early 90’s, the Zapatistas… it wasn’t all victories.

Now in the decades that they’ve been around, they’ve suffered many losses and confronted great struggles, but it’s been a successful revolution. I guess that’s just one of the important things that has to be noted in this discussion. The Zapatista uprising has been success, and that’s why in 2018 you can visit Chiapas and visit the Caracoles and actually witness a successful living, breathing and walking Revolutinoary society, small and embattled as it may be. And this other story that we’re talking about here, this kind of other Revolutionary movement that emerged in Oaxaca in the early 80’s and 90’s, is the story, sadly, of a failed revolution on the other hand.

It’s a story of a rose that failed for many reasons. Part of them might have been internal contradictions, but part of it was unrelenting and effective State violence. And it’s really hard to talk about what happened in Oaxaca and with the Loxicha prisoners and not refer it to what happened and was happening in Chiapas at the same time. It was about surviving. The Mexican state certainly tried to annihilate it, using military force against it, and could not. They couldn’t use military force and they were not effective with the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party / Partido Revolucionario Institucional), the long-term ruling party in Mexico. None of it’s large and well-tried arsenal of political, social-economic tools of co-optation was effective at undoing the Zapatista movement, either. It was somewhat effective, they lost some of their Caracoles/autonomous regions, but 5 of them, there they are!

But this is the reality that the Mexican State had to deal with in 1994, 95, 96. And with the emergence, then, of this other Guerrilla uprising with the face of the EPR, the Mexican State effectively made it’s project to take a different course of action then to basically annihilate them. Because of how well the Zapatistas grounded themselves, the state was negotiating with them and refused to do this on two fronts. They said “we’re going to recognize the Zapatistas as a political entity, we’re not going to say that specifically, but we’re at the negotiating table.” By 1996 you had the State negotiating with the Zapatistas over potential Constitutional reforms that would recognize Indigenous autonomy. As the EPR makes itself known, it’s strongest in parts of Oaxaca and Guerrero and parts of central Mexico, but the state at all levels organized itself to focus on the military solution to dealing with the Popular Revolutionary Army (EPR) and with other Indigenous communities that may or may not have been involved, may or may not have sympathized but where there was a risk of that… That was the Loxicha story. Yes, there was some presence of this revolutionary movement, the EPR, but in throwing so many people (including “innocent people” into prison) part of what you get is this sort of social punishment. It doesn’t matter if you were in or you weren’t, whether you knew or you didn’t. It was here, it was around you, so you were all going to pay for some kind of a random act.

Some of the high profile prisoners among the Loxicha prisoners, were the Municipal Authorities. So, essentially the entire democratically elected, local government of the municipality in Oaxaca, the majority of local government municipalities. More than 400 of the 500 of these entities, like counties, are ruled by Usos y Costumbres. It means that indigenous communities at the municipal level can determine their own way of electing local authorities and it also means that they do this to the exclusion of political parties. So, this is how the authorities in Loxicha are elected, that this has practically been happening pretty much always in indigenous communities in Oaxaca but had only become Constitutionally recognized one year earlier in 1995 as part of efforts of the Oaxacan State level (Mexico’s most indigenous state). It was their way of trying to placate the indigenous communities in the way of throwing them a bone in the form of recognizing autonomy to a limited extent. So obviously it’s not coincidental that it’s one year after the Zapatista Uprising.

TFSR: I was really curious about the relationship between the Loxicha uprising to the Zapatista revolution, and you spoke to that really really eloquently and I thank you for that because you know, the Zapatistas are world wide such a revolutionary example and are very very looked to, and the examples that they bring into revolutionary discourse are very cherished I think. And I think that it’s a really poignant situation to me when I’m hearing you talk about it cause these two things were going on so concurrently and one of them is way more lower profile and the one that’s way more lower profile somebody you know, was in prison for 20 years, you know? It’s very poignant to me that these two things were happening simultaneously. But yeah I thank you for talking about that, that wasn’t really a question it was just a reflection.

Bruno: I can actually say one or two things more about it, so I wouldn’t want to make it sound like the Zapatista’s fault that the Loxichas and the indigenous movement in Loxicha kind of was dealt a harder hand, you know I wouldn’t want to kind of say “oh well because the Zapatistas were getting all this attention people in Loxicha were screwed over”.

A way of understanding the different forms of attention they got but it’s very much to its credit that the Zapatista movement is still there today, and I think it’s partially due to the fact that they really knew how to organize. It’s why they’re there now. But I do want to say something more about the more substantial versus fair weather forms of solidarity.

So, one of the facets or one of the realities of the Loxicha story in its second phase as a story of many many political prisoners and their many families, tons of fractured families and fractured communities who then, while faced with a lot of violence, have to organize themselves in order to out of nowhere create this prisoner solidarity freedom movement, one important aspect of that Loxicha story as a prisoner liberation story is that the struggle was made particularly difficult by its association with this particular armed group, the EPR. So, while in the mid ’90s a lot of people wanted to be on board with supporting the Zapatistas because really they did have a very novel, very moving, very inspiring political message, which is why they really changed political discourse at the time. And a lot of people wanted to be involved with them, whereas the Popular Revolutionary Army, the EPR, at least kind of at its leadership level – this was a national, IS still a national organization, it’s still around – their discourse was fairly stuck in the past, it was still a very old fashioned stodgy Marxist-Leninism with a Maoist streak that really wasn’t speaking to people. To be honest, I’ve been studying this cluster of movements for years, and I find it really hard to get through a statement by the EPR through to the end, it’s just really hard to read.

[Interviewer laughs]

Whereas with the Zapatistas stuff, it’s impossible to put down! So there’s partly this: the EPR’s political discourse, its rhetoric, its public statements, don’t really inspire. Also the EPR comes out of the longer lineage of armed clandestine movements in Mexico, and some of these such as the PROCOUP-PDLP, which is the Partido Revolucionario Obrero Campesino Union del Pueblo – Partido de los Pobres. So this predecessor of the EPR, one of its predecessors, has a lot of dark associations; in the 1970s and ’80s that group was involved with a lot of violent infighting within its own ranks, there are these stories of so called “revolutionary trials” against its own former comrades, very foul treatment of its own political prisoners and then disavowing them, and in some cases killing its own former prisoners who had abandoned rank.

So there were these dark associations, some of which are on the level of legend some of which are actual, around this organization. And the fact that also then in 1996 when the EPR rises up, the Zapatistas who really are holding a lot of the world’s political imagination, or at least in Mexico and many other places, they’d already put down their weapons. The actual armed confrontation between the Zapatistas and the Mexican state lasted for twelve days. Then because the Zapatistas have always been really good at listening – the practice of listening has always been really integral to a lot of their political praxis on many levels – they heard this public outcry calling for an end to the war, and they put down their weapons and have since then, while there is still a revolutionary army that is a part of its movement and it’s not going away. But it has managed to successfully implement and develop its revolutionary society and communities without having to ever go on the military offensive since 1994.

Anyway at that point, it had been two years since then when in 1996 the EPR rises up, shooting up police and soldiers, and for several of these reasons then a lot of people weren’t that sympathetic when you then get this story of indigenous political prisoners who are all accused of being members of this particular revolutionary organization. And, you know it really doesn’t matter, clearly for most of them the Loxicha movement wasn’t the EPR. The Loxicha prisoners were really the product of a witch hunt, and you had a very diverse group of individuals in there. So because these many associations around the EPR, the state was very good at stigmatizing that movement. And so then as you arrest people who you accuse of being members of the EPR, you call them “terrorists”, and then it’s very easy to throw them away and to make people think twice before getting associated.

So as I began saying, a lot of people wanted to get on board with the Zapatistas in terms of NGOs, human rights organizations, legal aid, translators, all sorts of solidarity. But with the Loxichas, people were very hesitant. It was a very very limited kind of people, of organizations, essentially it was one of each category: one human rights organization, one team of solidarity lawyers, one NGO, that got on board with the legal and political defense of the Loxichas in the aftermath of ’96. And you know, this was making a full loop back to one of your questions, I think this is really one of the manifestations of the state being effective at using toxicity and stigma as it needs to. So here because of its political needs it was essentially effective at stigmatizing an entire community, a racialized stigma, such that for years young men or adult men from Loxicha would never say they were from Loxicha to this day. People will say they’re from the coast, or any other town, but people just won’t identify with being from Loxicha because it’s very dangerous. And nobody wants to get involved in anything that smells of Loxicha much less the EPR, because as late as 2007, whatever you say about the EPR the truth is that its own militants are still being disappeared by the Mexican state. So effectively being branded as EPR is to be branded as someone that the state might very well disappear or at the very least thrown into prison for years.

It became a very very toxic accusation, and that’s one of the byproducts of this whole conflict, of the Loxicha crisis.

TFSR: (Break audio) You’re listening to our conversation with Brunero Rennero-Hanan about the situation regarding Alvaro and Abraham Ramirez – no relation between the two – who are two out of the two hundred fifty original indigenous people arrested in the Loxicha region of Oaxaca in the mid ’90s. If you’d like to hear a 45 minute edit of this interview you can visit archive.org and search for The Final Straw Radio Collection. We’ll be back with the rest of the interview after a short musical break, what you’re hearing right now is Gabylonia with her 2012 release Abuso de Poder. Shoutout to subMedia’s hip hop podcast Burning Cop Car which is where I first heard this track.

[musical break]

TFSR: I’m wondering if you wouldn’t mid talking about who are Alvaro and Abraham personally, you mentioned at several points that you had a personal relationship with Alvaro, but will you talk about who they are and the projects that they do, and what is important to them politically these days?

Bruno: Yeah, definitely. So first how I got to know them -and I have a personal relationship with both of them, Alvaro and Abraham – because both of them were among the last 7 of the Loxicha prisoners. So of that group of prisoners that was upwards of of 200, maybe as many as 250 in the late ’90s, all those that were originally associated with this case there were still seven of them in prison in 2012. I started visiting them and interviewing them to record their oral histories. So, I started visiting Oaxaca regularly around 2008 because I was beginning my doctoral research around questions of social movements and historical memory, and originally I was interested in students around the popular assembly of the peoples of Oaxaca, and around then is when I became aware of the Loxicha prisoners who were definitely an old story, it’s kind of one of these long still breathing stories of state violence and grassroots solidarity that I didn’t quite understand too well but it was something that was because of the effervescence of the 2006 urban uprising of the Iapo, there was this rising to the surface of other forgotten or dormant political struggles.

I got to know Abraham and Alvaro in 2012 when I shifted my research from the popular assembly of the peoples of Oaxaca in that 2006 movement to the Loxicha story. And so I moved for a while to their community, to San Agustin Loxicha, where I lived for a bit over a year conducting interviews there and doing historical research, ethnography. At the same time that I started visiting them in two state prisons close to Oaxaca City, in Iscotel and Etla, I would visit these last seven of the Loxicha prisoners. I ended up getting to know five of them, or interviewing and recording the oral histories of five of them, and I got to know particularly well a few of them. In particular, Alvaro and Abraham as well as a couple of others.

So my relationship with them was from the beginning one of political solidarity and accompaniment as well as being centered around this project of recording their oral histories. It’s partly for my academic research in order to try and get this piece of paper, but I’ve often seen my role in politically engaged research as being someone who can amplify the voices of others, or share stories. That really became the basis of our relationship, the beginning was I would go and visit them, and six of them were in Iscotel Prison. This being kind of a low security prison, I would be able to spend several hours hanging out with them just listening and writing down stories in my notebook.

Low security prisons in Mexico might be kind of surprising to what Americans imagine prisons being like. The fact is that it’s still a prison, and a place that is locked up and constrained, but a place like Iscotel Prison, the prisoners didn’t have to wear uniforms. They could walk around in the periphery inside the gates, and around the building. And the Loxicha prisoners having been there so long, when I got to know them they had already been there for like fifteen years, they’d kind of accrued some seniority, some respect from both the guards, authorities, other prisoners. One of them was on his own in a different prison in Etla, Zacharias who became a master carpenter there, but the other six were in Iscotel. They were all in one single cell, cell 22, where several had been since 1996. Originally there were maybe 50 or 60 of them in two cells, but as they ended up slowly getting out and just those with the longest sentences remained in, the first six of them lived in cell 22 there in Iscotel Prison. And it was always striking to me that a prison, its main purpose is kinda to isolate humans, to de-socialize them, to try to extract them from society, and I was always struck by how limited the state could be for just how great humans are at subverting that. How the Loxicha prisoners had over these 15 years been able to carve out a little habitable space, a little human corner, within this dehumanizing place.

So Alvaro had also become a carpenter in prison, he’d picked up the trade there, and for instance built a second story inside the cell, what’s called a tapanco, kind of a little loft so that they wouldn’t be so cramped and that way two of them had their beds upstairs and the other four were down below. He also ended up building a little altar to the Virgin and their other patron saints, in Mexico it’s not uncommon at all to be leftist, even radical, perhaps even revolutionary, and still be devout, they’d organize events.

So anyway that was their life in there, and I got to know them through this relationship of interviews and recording their stories. The first time I got to know Alvaro actually was in the context of a forum that was organized by a collective known as La Voz de Loxiches Zapotecos en Prision, which is a collective that Alvaro is part of, along with some of his relatives and other supporters. And so they in conjunction with La Rev Contra la Revolucion, the network against repression which is part of the Zapatista network. So they collaborated to make this forum about Alvaro or for him, in solidarity with him, as well as other political prisoners in Oaxaca, in Chiapas. And the second day of this forum involved making a visit to Iscotel, so that’s kind of how I first went in. I was hesitant at first to just go in to try to visit them and say like “Hey I just want to hear about your stories.”

I thought it was important to first go in on the side of political solidarity rather than the side of oral history. And so my first encounter with Alvaro was in the context of the second day of this forum when about a dozen of us, including some members of his collective and relatives and then a few other anarchist-anarchist leaning comrades from Mexico City and Chiapas, Zapatista supporters who ended up going in and to my surprise ended up having a seminar – you know, sitting in a circle and discussing politics and prison with Alvaro himself – inside the prison. I never really expected that something like that could happen, so that to me was one of my early lessons in what effective prisoner accompaniment and solidarity looks like.

Let me tell you about them as well, and my impressions of them. So, of those last seven Loxicha prisoners who were in when I got to know them in 2012 and started working with a few of them, the first one I got to know was Alvaro. He’s the one I’ve gotten to know best so far, and this is partly because his political project and his views align the most with mine, and I’ve just found him to be a very inspiring and inspired political collaborator and interlocutor, he’s someone I’ve learned a lot from. But anyway so, Alvaro has been a political organizer and radical pretty much his whole life. He grew up in a small community called Iganoma Guay, which is a little village in the municipality of San Agustin de Loxicha, as a Zapotec speaker in a peasant family. I think he didn’t have a pair of shoes until he was 12 years old, he grew up farming but ended up working in the country side and then as a young man went to become a teacher.

In Oaxaca since the 1980s, which is when he started the teacher’s union, there has been a fairly powerful and at times radical movement. He was part of that original radical emergence of that kind of the Democratic Teacher’s Movement in the early ’80s, and then some of his early political struggles back in Loxicha, back near his home, were the establishment of schools for communities. Then in 1984 he was one of the co founders of the organization of indigenous Zapotec communities or pueblos, the OPIZ, and he also became a member of the local municipal government. So from the mid ’80s to the mid ’90s, Alvaro basically dedicated himself full time to becoming an organizer, and so this meant organizing the communities of Loxicha politically, internally, often in order to really try to break the power of casicas and pistoleros, political bosses and gun men in the region.

Loxicha was a place where political violence was really rampant, there was a lot of land theft, peasants were really badly exploited by middle men purchasers – coyotes – who would buy their coffee, this was a coffee growing region. And so some of Alvaro’s early struggles with the OPIZ were to try and combat some of the biggest problems of the communities which were poverty and that political violence and marginalization. He ended up being an important figure within the OPIZ through the ’90s and up until he had to go into hiding once the persecution of the movement began particularly in earnest, although he’d been in hiding and kind of living a partly clandestine life in the past before. And then he was arrested in 1998, as he mentions in that video that’s on the publication on It’s Going Down, he mentioned that he was detained in mid December in 1998 but then it wasn’t until 11 days later that he was actually presented at a prison and this was because for 11 days he was disappeared and tortured by the authorities who were trying to force him into making false confessions, to denounce his comrades, and this was something that happened frequently with many of the arrests and detentions of people from Loxicha. Many cases of torture and forced confessions, signing hundreds of blank pages.

So then Alvaro is later sent to state prison in Etla where he stayed for many years. He was a victim of an assassination attempt there several years later and then he was transferred to Iscotel Prison where most of the other Loxicha prisoners were. That’s where I got to know him. At the point when I got to know him he had gotten kind of a new political faith and he was by then the most politically active and most radical of them. I think several of the others were perhaps experiencing political burnout after so many years of struggle, of different failed options. And I think Alvaro also suffered from burnout, that’s something that I’m sure is common for prisoners in general. But at this point Alvaro was going through a kind of political re-animation that had been brought about probably a few years before when he became really invested in the project of the Zapatistas and particularly that which is explained in the 6th Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle. That has really become one of the most important parts of his political project since then, he kind of found a new political energy at that point sharing it with other prisoners, trying to enact it. I think the Zapatista discourse really served for him to re think a lot of his current political practice; inside the prison he started thinking about how to think about new forms of organization, how to talk to other people about horizontal organizing and autonomous work, how to get that message through in a successful way.

He also began corresponding and engaging with other prisoners who were adherents of the 6th Declaration of the Lacondon Jungle. And I think it also served partly to reinterpret his own political trajectory and his past.

Some of the most insightful and exciting political discussions I’ve had were with Alvaro, and his daughter and her partner who were some of the members of the collective that has supported Alvaro for many years, at least since 2009, built around this Zapatista model. Not that it’s trying to replicate, but to just use some of those basic principles. And some of that work has been around re-thinking as people in solidarity with him, cause his relatives are his allies but also for himself, kind of re-thinking what it is to be a political prisoner as a political subject. To re-think what solidarity looks like, that solidarity isn’t charity, or a favor, that it’s not done for someone but with someone. Really trying to place a political prisoner at the very center of his, her, their struggle for liberation. So in sum, Alvaro is someone who has inspired and taught me a lot about prison, about freedom, about solidarity, about autonomy. His Zapatismo has become a really influential thing for him, and so as soon as he got out of prison in 2017 one of the first things he did was, instead of now just corresponding with that Zapatista network and that network organized by adherents of the 6th, he went and started meeting people.

He got involved immediately with the campaign to support Marichuy, the potential candidate for the National Indigenous Congress, was kind of a recent Zapatista project to try to subvert the national elections in Mexico. He joined the campaign to support her and get signatures, and joined their tour through southern Mexico and followed them to the Zapatista communities. He ended up visiting all 5 caracoles, which I know a lot of people who claim to be Zapatista supporters who haven’t visited even one, certainly not 5!

He had just gotten out of prison, been inside for 20 years, that’s a scary moment for a lot of people getting out of long term incarceration. People are often very flustered, maybe kind of scared, suffering from some trauma. He certainly had no money but he somehow just made it work.

And then I can tell you about Abraham. Abraham was one of the next prisoners that I got to know by recording their oral histories. Abraham Garcia Ramirez is like Alvaro someone who grew up very poor in a rural community in the municipality of San Agustin de Loxicha, he’s from Santa Cruz. He tells a story about not being able to get past the 5th grade at the closest school because he suffered an accident when his teacher’s donkey had a rope attached to it that accidentally caught on his leg and ended up dragging him several meters and messing up his leg really badly to the extent that he couldn’t walk. And his parents were afraid to take him to a doctor because they were afraid that they would amputate his leg, which may sound silly but it’s not a story about these ignorant parents, those stories are expressions of what structural racism and poverty look and feel like where indigenous people, speakers of Zapotec like Abraham’s parents, were generally treated so poorly with so much derision, discrimination, by authorities, by doctors, judges, police, people who held power, it was so common that they were afraid that if they took their son in that they would sooner amputate his leg than fix it.

So Abraham tells a story about not being able to back to school because he basically sat at home on a little stool for a year and would just read by himself. He sat on his own, he continued working as a coffee cultivator from a very early age. Then in his youth he ended up getting involved first through a kind of leftist political party, the PRD, on the coast of Oaxaca, and then I think being disappointed with party politics, he ended up then hearing about the indigenous movement of the OPIZ that was forming back in his hometown and around Loxicha. And when he went back there in the early ’90s he ended up getting involved.

And so I would say that Abraham like Zacharias, another of the last prisoners to get out, were part of kind of like a second generation of all these militants and community organizers. So Abraham was very charismatic, he was very charming and effective political organizer, so at this point the OPIZ in the early ’90s really had a lot of political presence throughout most of the 70 odd towns and villages that make up the municipality of San Agustin de Loxicha. So Abraham was someone who was organizing people to organizing assemblies, getting people to come out. Things he would do would be to organize in communities internally to counter an absence of the state in many places, to be able to deal with problems on their own whether it was questions of, say, domestic violence: Abraham would say “ok we’ve got this problem, how do we get to the root of it?” This led to women organizing themselves and saying that alcohol was one of the biggest problems behind domestic violence in the communities, and so many communities ended up banning alcohol. Enacting that kind of local change was part of what these organizers including Abraham were doing as well as in some cases organizing to make demands of the State, whether through negotiating with the State itself at points or organizing enormous marches of hundreds or in some cases thousands of people to take the highway and march to Oaxaca City, four hours to the north, or to occupy the central plaza in Oaxaca, to take the airport.

So then by 1996 when the EPR uprisings happened, Abraham was a well known organizer. And certainly the State had its eye on him, because he’d been one of the important organizers in taking the plaza in Oaxaca City, the airport. So it was very easy to pin the guerilla accusation on him, as well as many others who were well known activists or organizers with this organization of the OPIZ. By the time I got to know Abraham as another of the long term prisoners who’d been in for decades, he always struck me for being extremely humble. I’m not sure if that’s the most flattering thing..

TFSR: It’s not necessarily like a quality you would find in – you mentioned that he’s very charismatic and very charming, and humility is a really interesting character trait to go along with those two things. I don’t often find that.

Bruno: One of the striking things about Abraham is that he is humble, and you’re right that is sometimes an unusual feature in charming or charasmatic figures. But that’s I think one of the things that’s notable about indigenous and peasant movements in a place like Mexico, I was always struck by the motto or the principles of the organization that Abraham and Alvaro were militants in back in the ’80s and ’90s, the OPIZ, their 3 core principles were discipline, honesty, and humility. And you say ok, discipline and honesty are pretty standard fare for the values of activists, maybe even revolutionaries, but humility is not something you often find in the espoused values of revolutionary movements. But I think it’s certainly an expression of this being a peasant and indigenous movement rooted in the country side, and humility is something that’s really highly valued in the communities.

And it’s something like someone like Abraham certainly really lives by. By the time that I got to know him better and was recording his stories, he was not as politically involved. At that point he was a bit more focused on his legal case, plus he had a baby daughter; he’d separated from his previous partner in prison and met another partner there. This was at that time a co-ed prison, and they had a baby daughter who was born there in prison, and in fact grew up there for the first couple years of her life, and that was really the main focus of his attention at that point. Now currently, since he got out in 2017, he’s returned to some of his organizing but at a very local level. I think he’s been re adjusting to life on the outside slowly, but he’s been living in a shelter that was one of the material gains you could say of the Loxicha Prisoners Movement. They eventually managed to extract this shelter from the State in a concession in the early 2000s where now several families who were victims of state violence in Loxicha now live. It used to be mostly for families of prisoners to be able to stay in Oaxaca while they visited from Loxicha.

But anyway, now people who were victims of violence in different forms now live there, and Abraham and Zacharias are both living there. Abraham is kind of taken upon himself to reorganize the space where you’ve got dozens of people living in order to make it a little more comfortable and clean and pleasant for the people living there. And on that, he’s also working to try and support himself and his family, his wife who’s still in prison and his smallest daughter who’s 5 in school. He’s weaving baskets to support himself like that, to try and help his comrade Zacharias to set up a carpentry workshop. And that’s what he’s up to these days.

TFSR: One of the reasons that we both are talking right now is that they are out of prison, but they are being forced to pay some pretty exorbitant fees to the Mexican State for so called “damage reparations”. Could you talk a little bit about what they are being forced to pay per month and is this a common tactic on the part of the Mexican State for extracting funds from former political prisoners?

Bruno: Yeah, so Alvaro and Abraham got out finally after 20 years in prison, on July 7th of 2017. And so for 20 years the demands for them and for the other prisoners has always been immediate and unconditional freedom. And finally they were able to get their freedom after being robbed of 20 years of their life, but in order to accept it they basically had to sign onto a really sordid deal where in order to be recognized as being accepting of a quote unquote “early release”, because at this point their sentences were around 30 years, and having gone through 2/3rds of their sentence and proven that they are well behaved or something like that, then they were granted this so called benefit of being given an early release. In order to do that they said ‘we’ll give you the early release but you have to accept a whole list of conditions’ some of them just kind of being symbolic nonesense, like “I promise not to do drugs or commit crimes”, but also they had to promise to pay these so called damage reparations to the court. Which allegedly are a way of monetizing the deaths that they accuse them of causing. But really this is just ransom money that goes to the courts.

So each of them are being charged slightly different figures, but close to around 125,000 pesos, which is sort of like 7,000 dollars depending on the exchange rate, over the course of 2 years. Which translates basically to paying in the case of Abraham 250 dollars more or less to the courts each month and for Alvaro, about 280 dollars each month. Which is a ludicrous amount! I mean I would find it hard to be paying that each month on top of my rent, and frankly the kind of money that you can come by even as a relatively modestly living person in the US is impossible compared to Mexico. So to assume that ordinary people, not to mention poor people, could pay this in Oaxaca is unrealistic. Not to mention people from rural communities who happened to have spent the last 20 years in prison and just got out. It’s just another slap in the face right, this added injustice heaped on top of a mountain of injustices, the core of which is 20 years of prison built of course on top of all the injustices that led these people to rising up against the State in various forms, or confronting the State, and then being made political prisoners. So anyway, this is just yet one more injustice. And part of why we’ve taken it up here.

Through my connections with the Loxicha prisoners to help out however I could, and we’ve taken it up here in the US, even though there’s a network of support for Alvaro and Abraham in Mexico, it’s just doing something in the vein of economic solidarity is much easier here in the US. Even just a few dollars that might not be a lot to people here, even ordinary people who might have low-paying jobs, just a couple of bucks a month is something that we can afford. If we hit up some wealthier Liberals, maybe they can throw in some more. That’d be great! But even with some very small donations built up from a pool of friends and comrades, I think we can hopefully get to covering that $530 a month that would cover both of their damage reparation fees. Thus, helping them to not be forced to go back to prison. That’s really the punchline behind this. They’re being charged these damage reparations, essentially ransom by the courts, under the threat of being forced back into prison for another 10 years.

They both realize that this is a threat that they face and they’re both very philosophical about it, but it’s impossible to fathom (for them, their families, friends) that they’d go back in for another 10 years for this completely unjust and counter-insurgent political imprisonment.

TFSR: In a recent statement by Alvaro that’s posted on ItsGoingDown, he makes a declaration of solidarity with the J20 defendants and he calls the process “an attack against the youth who resist, reveal themselves and rebel.” Will you talk about the parallels between this case and those of the J20 defendants, 59 of whom are still facing decades in prison?

BR: Gladly. To be forced to think of the parallels between the Loxicha case and the J20 defendants amongst the friends and comrades here in South East Michigan who have worked with us to start this economic solidarity project with the Loxicha Prisoners, Abraham and Alvaro, that includes a couple of the J20 defendants who live here in Michigan. As we started up this economic solidarity project, I was really pleased, I thought it was really cool, that these comrades in the J20 defense, were keen to help out. And then it struck me that it made perfect sense, that you would get really heart-felt solidarity without having to really think about it much from folks who are facing the prospect of political imprisonment with people who are just emerging from it. The conditions and situations of the two movements are different in many ways: one in the United States during the Trump Era; the other we’re talking about in the mid-90’s in Mexico. And yet, the parallels are looking at violence and political imprisonment from opposite sides of a prism.

It’s sort of like in the case of the J20 defendants, you’ve got this original group of around 250 (coincidentally 250 people arrested and accused of ludicrous crimes, these really symbolically charged & trumped up charges aimed by the state at putting dissidents behind bars and at dissuading people from dissenting against the state; politically motivated use of the courts and of prisons to scare people, to inflict a bit of terror against dissidents or possible dissidents… Even among the J20 defendants, it was very clearly targeted against people who were marching under the banner of anti-capitalism, anti-fascism. But you’ve also got people who were thrown in there who were journalists, photographers, who weren’t directly involved in protesting but it doesn’t matter, it’s a part of the message. Similarly in Loxicha, in the mid-90’s, again you’ve got different conditions, but a group of around 250 people who were arrested, detained, sent to prison, under these symbolically loaded political charges. Again, some of them were resisting, protesting, organizing against capitalism and the State. Some of them just got caught up in the violence, swept up in the witch-hunt. And yet, I think that what caught the imagination of these comrades who are J20 defendants in Michigan who want to support Alvaro and Abraham is to think… Here the J20 defendants are looking down the barrel, looking at the prospect of decades of political imprisonment for resisting the state, for protesting it. And they’re looking at these comrades in Mexico, from very different worlds, but one which also for resisting capitalism and organizing these hundred of people. Instead of looking at the prospect of it, they’re emerging from decades of political imprisonment.

This led to conversations here about how there must be a lot to learn from one site to the other. What can folks who are young organizers such as the J20 defendants, what can they learn, what can we all learn from listening tot he story of people who did suffer through decades of political imprisonment. And the other way around, what can folks like Alvaro and Abraham learn from new forms of resistance and solidarity that are emerging from and being expressed by something like the J20 defense. So, it was this cool surprise here to get J20 defendants in on the project and to have these discussions and to compare the two phenomenon. And then, when some of us visited Alvaro this past December, we had a visit with him now the first time in freedom, recorded this video, did some interviews. We were talking about J20 and the J20 defendants so, on one had he hadn’t heard about the J20 (which shows that we need more communication across Leftist networks internationally) but then we had a really great conversation where we explained what had happened on J20 and the situation of the defendants were.

It took so little explanation, he was immediately captivated, perceptive, clapping his hands “Of course, that makes perfect sense. Obviously these are the repercussions, this is what the State did in reaction to those who are marching under the banner of anti-capitalism and anti-fascism.” And we had one of those classical, great discussions that Alvaro is fantastic at, discussing some of these comparisons. One fo the great things to come out of it was that we kind of proposed that this could be the beginning of some exchanges. We thought it’d be really great to organize some form of dialogue, exchanges, encounters somehow between Alvaro, his comrades, the former prisoners in Mexico and J20 defendants and their allies in the US to give this conversation some actual substance. And there, Alvaro and comrades offered then that they could disseminate that and share it in a newspaper like Unios (a newspaper of the network of adherents of the 6th Declaration [of the Lacondon Jungle, the Other Campaign of the Zapatistas]).

TFSR: That’s so wonderful that it was such a productive conversation. That makes me really happy to hear that and congratulations for being a part of that and for setting that up and drawing those parallels. I think that’s really really awesome.

BR: Thanks. And out of that conversation is where Alvaro wanted to send a shoutout to the J20 Defendants that we recorded that’s on the video on Its Going Down. So, I have to confess that last line in the video which you quoted where he says “we recognize this as an attack against the youth that organizes and rebels and reveals itself”… I was the one who wrote the subtitles on that video. I was translating this letter which he was reading from. The word “to rebel” in Spanish, which is “que se rebela” he spelled it “revela” which means “reveals itself”. I knew he meant “rebels” and I wondered if whether that had been purposeful, so I translated it as both: it both rebels and reveals itself. You never know, was it a slip of the pen or that might have just been Alvaro’s message itself. In one word, you both rebel and reveal yourself.

TFSR: I liked it very much, especially in the context of J20, which was a Black Bloc, which is supposed to be an anonymous thing, that was then revealed by police, it was then also… people were doxxed by fascists and members of the alt-right. I found it to be a very great, linguistic insertion. Like, you revealed yourself, that’s courageous, you rebelled and that was courageous. I thought that was brilliant.

BR: I love that. And you know, you’re totally right. You mention, it was the Black Bloc where people concealed their identities, their faces, and that they do so in order to reveal themselves., in order to rebel. It’s kind of like what the Zapatistas did in covering their faces. “In order to be noticed, in order to have a face, we had to cover our faces.” I’ve always loved that through this kind of anonymizing yourself, you become someone.

I kind of imagine that in rebelling and revealing themselves, Alvaro might be saying that in that act of rebellion that you reveal yourself, not only to the State, to others, but even to yourself. People discover themselves in that moment of action, as Frantz Fanon said, “Consciousness is born in action, not the other way around.”

TFSR: Could you remind us of the Patreon link and talk a little bit about the economic solidarity project / endeavor being organized under the banner “Keep Loxicha Free”?

BR: That’s kind of the main focus of what we’re tryihng to organize with this economic solidarity, so I really appreciate the change to broadcast it a bit. For most of us who are working on this, this is our first time doing this kind of economic solidarity. I, personally at least, find that economic solidarity can feel kind of tricky or off-putting. Economic Solidarity is one tiny fragment, one tiny instance of what solidarity can look like. And I think for those of us who are further left, with anarchistic leanings, Zapatista sympathizers, dealing with money is something that’s really uncomfortable. We don’t like doing it and it’s partly why Alvaro and Abraham themselves have not been able to raise that money.

A couple of the other last Loxicha prisoners who got out last year had the same conditions but were able to raise that money through connections to Unions or through asking the State. Alvaro and Abraham had not wanted to do that. A part of the way that these ransoms work in Mexico is that you have to ask someone powerful to help you out and you end up indebted. So, what we’re trying to do by bringing that economic solidarity pitch here to the US (and

internationally, if people want to donate) is to try to take that weight off of having to ask for the money over there. Instead, we said “let us ask for you, it’ll probably be easier.” But several of us have never done fundraising, so it’s figuring it out as we do it. We thought that one of these go-fund-me type pages would work and that Patreon with it’s monthly donation system would work for this.

So, we’re trying to work up to $530 per month, we’re currently at $201, almost halfway there. In recent months we’ve been making this work also by presenting this story at events, going to events organized by comrades and friends, and making little 5-10 minute pitches and passing the bucket. Through that along with the Patreon we’ve been able to cover their payments so far. But you can only present so many times in your community and pass the bucket, so we’re really hoping this Patreon website will be a self-sustaining effort so that for the next 2 years Alvaro and Abraham will be covered and don’t have to live every day with this hanging threat the moment you wake of “if I don’t pay this money, I go back to prison.” So, that’s what we’re trying to do with the Patreon site. https://ww.patreon.com/keeploxichafree

TFSR: Bruno, thank you so much for taking the time. I got a lot out of talking with you about this topic. Many thanks and solidarity from here!

BR: Thank you so much, I really really appreciate the space. I really appreciate the attention. There are a lot of things that you all could be covering, so I appreciate that you also thought this was important and were willing to open your space, your time for this story. Also, thank you to all of the listeners.

Again, hopefully, what we’re trying to do is to plug that Patreon website, but we also think it’s really important just to be having these conversations. A part of this is that we want to raise this money to help our comrades, but we also think that sharing their story, their testimony, their experience and also our own experiences. Making that a conversation is really an important part of building grassroots solidarity, awareness and political education. I’m really glad to be a part of the conversation!