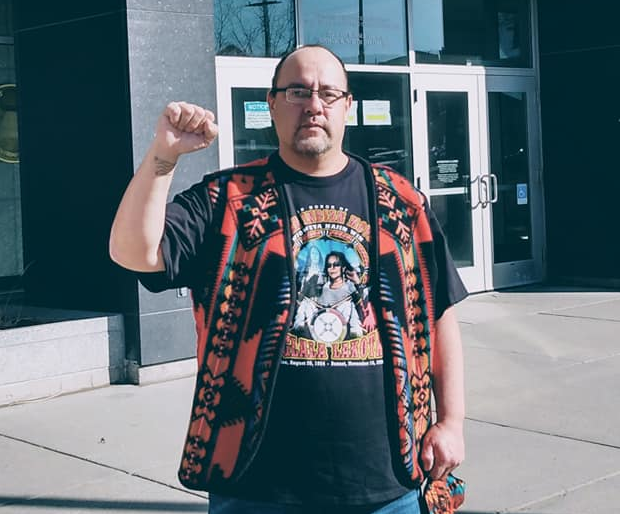

Steve Martinez Still Resists Grand Jury Related To Dakota Access Pipeline Struggle

It’s been nearly half a decade since thousands of indigenous water and land defenders and their accomplices and allies weathered a difficult winter and attacks by law enforcement and private security attempting to push through the Dakota Access Pipeline through so-called North Dakota. The DAPL was eventually built and has already, unsurprisingly damaged the lands, waters and sacred sites of the Standing Rock Sioux and other people native to the area. Resistance has also continued to this and other extractions and pipeline projects across Turtle Island and the defense against DAPL surely inspired and fed many other points of opposition in defense of the earth and native sovereignty.

On one night in November, 2016, as government goons leveled fire hoses and “less-lethal” armaments at water defenders in freezing temperatures, Sophia Wilansky suffered an injury from an explosion that nearly took her arm. An Indigenous and Chicano former employee of another pipeline project named Steve Martinez volunteered to drive Sophia to the hospital in Bismark. For this, he was subpoenaed to a Federal Grand Jury, which he refused to participate in. Now, almost 4 and a half years later, Steve is being imprisoned for resisting another FGJ in Bismark. For the hour, we hear from Chava Shapiro with the Tucson Anti-Repression Committee and James Clark, a lawyer who works with the National Lawyers Guild, talk about Steve’s case, the dangers of Grand Juries, and why it’s imperative for movements to support their incarcerated comrades.

More info on the case and ways you can support Steve, plus more info on Grand Juries can be found at SupportSteveMartinez.com and you can also follow the campaign on Twitter via @SupportSteveNow, Instagram via @SupportSteveMartinez and donate at his GoFundMe.

. … . ..

Featured Track:

- Deep Cover (instrumental) by Dr Dre

. … . ..

Transcription

The Final Straw Radio: Would you please introduce yourselves to the audience with any names, preferred pronouns, affiliations or other information that pertain to this chat?

Chava: My name is Chava I work with Tuscon Anti-Repression Committee in Tohono O’odham territories, also known as Tucson. And I have done anti-repression and movement defense work for around 13 years, and grand jury support work for the last four or five years. And I use they/them pronouns.

James: My name is James, I use he/him pronouns. I’m a lawyer with the National Lawyers Guild based out of Austin, Texas. And I’ve also been doing anti-repression and activists legal support for about 13 years now, including a number of grand jury support situations.

TFSR: So would you please tell us who’s Steve Martinez and how did he come to be called before a federal grand jury after a brutal night in November of 2016. And what happened with that grand jury back then?

C: Steve started out coming to Standing Rock, really thinking that he was just going to drop off water. And he actually had been working in the oil fields, the Bakken oil fields in western North Dakota prior to that, heard about what was happening at Standing Rock, and was really inspired by what he had seen and heard about happening, even though he was also working for the oil fields and the oil company.

He’s Indigenous from Pueblo community in northern New Mexico and also Chicano and grew up in southern Colorado, and just inspired by the Indigenous land resistance and movement happening. And so he loaded up his vehicle with water to come and take it to the camps, and then he never left. And he became really involved in what was going on there. From the point of the summer, all the way up to that night that you mentioned in November. Which a lot of people remember that there were fire hoses used – and, you know, sub freezing temperatures – by law enforcement on water protectors that night in a conflict that lasted, you know, 12 to 14 hours on the bridge in those cold temperatures. And a young woman named Sophia Wilansky was really gravely injured that night, presumably due to law enforcement’s use of so called “less lethal munitions”. She nearly lost her arm.

When she was injured, getting emergency services was almost impossible for emergency vehicles and services to get to that point on this highway that had been blockaded by law enforcement at that point for around a month or more. And in order for her to get to emergency services, she would have to be driven by someone who was on the other side of that blockade. And that person who volunteered to do that was Steve, who was acting as a Good Samaritan doing the right thing in that moment. And then just really, a handful of days later was subpoenaed before a grand jury. And his presence was requested to provide information – they said they were asking for information – related to Sofia Wilansky’s injuries. So any testimony he could provide, or any images he might have taken on a cell phone or anything like that.

Steve didn’t know what that subpoena was when he received it. And so he reached out to a relative that stayed in the same camp that I did at the time – I had gone up there to do legal support for people – and his relative then came to me and said “Hey, can you speak with my uncle? He’s received some kind of subpoena we don’t really know what it is.” And at that time, just pulled his uncle into a tent and that uncle turned out to be Steve, and immediately from that moment that he received that paperwork, he asked for support, and then happened to have one of the best, most knowledgeable movement attorneys on grand juries in camp that day, which is Lauren Regan from the Civil Liberties Defense Center.

You know, maybe it’s just pure luck. Maybe it’s, you know, serendipitous, or that Lauren happened to be there that day. But we were able to immediately get Steve talking with an attorney who could explain to him the process. And then also from that exact day, moving forward, it also began a massive outreach with the thousands of people who were staying in camp at that point, about grand jury occurring subpoenas going out, at least one known subpoena at that point. And then also initiated the nationwide education campaign, because many tens of thousands of people had come and gone from the camps. And so that is where Steve was four years ago. But almost exactly four years later, he was subpoenaed to this new grand jury. And he, again, has refused to comply, because he’s acting in immense solidarity with a movement that he believes in, which is a movement for Indigenous sovereignty over lands and waters, and to protect those things, and a deep love and care for his comrades. And so that’s where we are now. And how we got there.

TFSR: Do people feel like they have an understanding of what this grand jury is specifically about? And does that matter?

J: We’re quite confident that it’s about the situation regarding Sofia Wilansky. One sort of important development between Steve’s grand jury subpoena in 2016, and when he got subpoenaed again in 2020, was that Miss Wilansky has sued Morton County over their use of, you know, these “less lethal munitions” that caused her injury. And in, I can’t remember if it was October or November of 2020, the judge in that Civil Lawsuit made a ruling that she could seek to compel the government to disclose evidence, specifically the fragments that were taken from her arm during surgery. And it was just a matter of days after that court’s ruling in the civil lawsuit that Steve was, again, subpoena to this grand jury. So it’s kind of you know, the timing is is convenient, as they say.

C: Yeah, I think you spoke well, to that, James, the timing is is suspect. And I think it’s also interesting to note that throughout the whole course of legal battles related to Standing Rock – both criminal and civil legal battles – there has been some signs of real collusion between civil court and criminal court. There’s been a number of attempts at SLAPP suits and civil suits by ETP (Energy Transfer Partners) that continue even now. And this timing of, you know, this win in Sofia’s case with that judge to compel the government to turn over this evidence – which I’ll just note there were FBI agents lurking outside of her surgery room outside of the OR, waiting to confiscate those items, while her family is like crying in a hallway. I just think it’s important to remember the cruelty of the state in the course of this entire situation. Because I don’t think that’s most people’s experience when they’re in a really scary, dangerous situation that involves possibly losing a limb or use of that limb.

And so the way that it looks like, the government has been able to make sure Sophie’s attorneys cannot get that evidence back from the federal government is by saying it’s part of an ongoing investigation. And so if there’s a new grand jury looking into these facts from, who knows, what, four years ago? Then they can’t turn that evidence over to the civil court, because there’s this ongoing criminal investigation. So it seems pretty well timed and convenient on their part, and really just a continued leverage of cruelty against Sofia, and against other water protectors who were injured and harmed at the hands of law enforcement. And also unbelievable amount of cruelty leveraged against Steve, who, all he did on that night was the right thing. And now, four years later, he’s dragged back before a grand jury in what seems like just using him as if he’s upon, but he’s a real person with a family and a life. And now he’s separated from them while he’s incarcerated.

J: I think the other key portion of this story, and the cruelty the Chava is talking about, is how Morton County has tried to basically twist the narrative, while all the evidence that we know about points to Morton County law enforcement being responsible for Sofia’s injuries and for the use of these “less lethal munitions”, they’ve always tried to either directly say or insinuate that this was actually caused by other water protectors, or potentially even by Sofia herself. And so the sort of victim blaming narrative that they’ve tried to use to tar the movement, kind of like what, you know, what the government did with environmentalist Judi Bari, you know, when her car got bombed, and they tried to blame her for that. And so it’s kind of a continuation of that, bad actors will inflict horrible violence on activists and then try and twist the narrative to blame the activist for that violence that they’re inflicted.

TFSR: So this is a beginning of a long conversation, but can you tell us a little bit about grand juries? They’re a pretty complicated legal tool that is shrouded in mystery. And yeah, just kind of remind us about what they are, how they operate, and sort of their range and uses, from the mundane to political repression?

J: Yeah, absolutely. Most of the uses of grand jury are pretty mundane, you know, speaking here, specifically about federal grand juries, because it can vary a lot from state to state, whether there are grand juries or how they work. But in the federal system, pretty much every felony case goes before a grand jury. And the purpose of the grand jury is to decide whether or not the government has enough evidence to even bring charges against somebody. It’s supposed to be a sort of screening or gate-keeping kind of function, to make sure that people aren’t brought to trial on serious charges without, you know, at least some amount of evidence. That’s sort of the ideological idea behind fair use.

In practicality, it tends to be much more of a rubber stamp. But there’s a famous quote from a judge in New York that “a grand jury would indict a ham sandwich if that’s what a prosecutor wanted”, because the prosecutor controls the entire process. And so, in most grand jury proceedings, what happens is that a federal law enforcement, federal agent of some type, will go to the grand jury, maybe summarize a police report, give some facts, some details, and the grand jurors will decide if that’s enough evidence to constitute probable cause to bring charges against somebody. And it, you know, typically, pretty quick proceeding, you know, the cop says, “Oh, we did this raid, and we found these drugs, and these people were there and we know that this was their apartment.” And so in that way, a lot of the grand jury uses are kind of unexceptional, even if it is a still problematic in regards to how much power and control it gives to the prosecutors in this system.

In a more political context, what we see though, is actually using the grand jury as an investigative tool. As a way to compel witnesses to appear and give testimony, or compel people to turn over evidence of some type. And this is where we see, you know, analogies to grand juries is like a fishing expedition or a witch hunt, or something. Where people are sort of dragged before these legal proceedings and forced to, you know, name names or give evidence, or something of that sort.

And so, the way the grand jury works is that there’s typically, I believe, 24 jurors – so it’s twice as big as what you think of as a typical jury in a trial. There’s 24 jurors, and the only people in the grand jury room at the time are the grand jurors themselves, the United States Attorney, the prosecutor, the court reporter, maybe some clerical staff and the witness who’s giving evidence. There’s no defense attorneys, there’s no judges, there’s no audience. It all happens very much in secrecy.

And the other aspect is that, you know, sometimes we think about how in a jury trial you have the lone holdout juror that prevents somebody from getting convicted. In a grand jury proceeding they only have to decide by a simple majority. So you can’t have a single lone holdout grand juror, because as long as 13 people still vote to charge somebody or to indict somebody, the other 11 people, their votes don’t really matter.

Grand jurors, again, in opposition to what we normally think of in terms of a jury, grand jurors are not screened for bias. There were situations during grand juries that were investigating alleged acts of Animal Liberation, Earth Liberation groups, where people that basically worked in the industries that were being targeted by these Animal Liberation groups, other people in those industries, were actually sitting on the grand juries that were reviewing the cases that were, you know, allegedly targeting those industries. So there’s no screening for bias. It’s, you know, supposed to be a cross section of the community, but it’s kind of random. And there is a long history of discrimination in who gets selected to sit on a grand jury, who gets selected as the foreperson of the grand jury.

And so, you know, what turns into is this, you know, secret of proceeding with almost no oversight or accountability, where the prosecutor has total control over what evidence they present, they don’t have to present contradictory evidence, they don’t have to present exculpatory evidence, they don’t have to present anything that would be unfavorable to the outcome that they seek. They can present the evidence in whatever light they want. And they can also present evidence that, you know, is illegally gathered, or that wouldn’t be admissible in a normal trial. So things like hearsay, rumor, gossip, evidence that was collected as from illegal search or seizure, statements that were maybe coerced or compelled in a way that wasn’t constitutional, all this all this evidence can be presented to the grand jury, in furtherance of what the prosecutor wants to see happen.

Considering the scope of this, another thing that we see in some of these political cases, is, you know, people getting called to grand juries, to testify about things that are sort of far afield of what they directly experienced. There’s one case where somebody was being asked to testify about something that he allegedly overheard two other people saying, at a bar or coffee shop. Not something that he was directly involved in or directly participating in, but sort of this third or fourth hand rumor that he had overhear.

TFSR: As you mentioned, James, the witness that’s being called before the grand jury, is seated before grand jurors, the prosecutors, stenographers, the, you know, court officials, doesn’t have a lawyer present, right? And a lawyer could hypothetically, if they had a role there, challenge some of those things that might be inadmissible normal court setting. But they also can’t really warn someone about safe approaches towards answering the questions or not answering the questions. Are there safe approaches?

J: So, I mean, this is getting into, you know, sort of the difference between political advice and legal advice. I’m obviously not here to give anybody legal advice, and if anybody’s ever called before grand jury, they really need to have a good lawyer that shares their values and their goals to represent them and inform them of all the nuances and implications here. Politically, I would argue that there is no safe way to answer questions at a grand jury. And this is for a variety of reasons. I think one reason is that you don’t know what they’re looking for. People have an idea that like, “I didn’t do anything wrong”, or “I don’t have anything to hide” and I think that’s generally mistaken. I think part of it is the broad expanse of federal law that things that you wouldn’t even imagine are illegal and felonious under federal law, so you don’t know what’s going to incriminate you or incriminate somebody else. You also don’t know what somebody else might be exposed to. Maybe you have a reasonably good idea of what actions you’ve taken and what things might put you at risk, but you don’t know what your best friend or your family member, your comrade, or your neighbor, your fellow organizer, what they might be subject to. Things that might seem supposedly innocuous or harmless can easily cause significant problems for people.

The other thing that we see is, you know, we have this idea of like, back in the Red Scare McCarthyism, people getting dragged before hearings and being forced to name names, and then everybody that they name then also gets dragged before the hearing in kind of this dragnet approach to investigations. And that’s entirely possible with grand juries too, that the mere fact of you identifying somebody else, even if it’s not in a way that criminally incriminates them, could be grounds for them to get dragged in front of this grand jury also. And then they’re faced with this sort of impossible situation where they have to either decide to testify or face imprisonment for contempt.

And I think, you know, again, speaking politically, I think the idea of solidarity and building trust and cohesion and our movements is really fractured when somebody that’s involved in those movements goes before a secret grand jury and gives testimony that there’s no accountability or transparency for. It’s often hard for people to trust one another in that situation. So that’s how grand juries can serve to sort of, sow this distrust and paranoia and discord within movements and really fracture the solidarity that’s necessary for effective organizing.

C: Bursts, you said in the beginning of your question “Is there any safe way to answer questions before the grand jury?” And, James, you spoke really well about all of the reasons they’re not. That question you asked Bursts is sort of a gateway into strategy that we’ve seen be effective in recent years for resisting a grand jury.

There’s essentially four ways somebody can resist a grand jury: you can avoid being subpoenaed, which means you need to know that there’s a grand jury happening, and that’s actually a lot harder to avoid a subpoena than it sounds. But a subpoena for a grand jury does have to be served to you in person by a federal agent, by a federal law enforcement agent. Doesn’t have to be an FBI agent, it could be an ATF agent, or a CIA officer or whatever. But you’d have to avoid that person. And know that they were coming for you.

You could also receive a subpoena and you could just disappear. Some people have used that strategy to varied success, but it’s very difficult. Because it means you have to basically go on the run, you’re avoiding complying with that subpoena. And it means that you would have to leave the place where you normally live, stop talking to people you normally speak to. And that’s a really difficult way for somebody to exist.

The other thing is that you could receive a subpoena and you can publicly refuse to enter the courtroom. And some people have done that very successfully. Because even entering the courtroom, like James said, we don’t know for sure what’s happened in there, right? So all of your comrades, and the larger movement on the outside of this secretive process, we don’t know what’s going on in there. So you run a risk when you enter the courtroom that potentially could leave some room for mistrust amongst the movement.

But we have also seen this last option where you receive the subpoena, you publicly refused to cooperate, but you enter the courtroom and then you invoke your constitutional rights that apply in the situation and your refusal to testify. Which is the tactic that Steve has used and other recent grand jury resistors have used successfully, is that it sets up a great legal precedent for getting you out of the legal consequence that occurs when you refuse to comply with the grand jury. Which is if you refuse to comply, you could be held in civil contempt for up to the length of the grand jury, and that could be 18 months. And that’s a long time, but we’ve seen the use of this legal maneuver, called a “grumbles motion”, which basically appeals to the judge who’s holding you in a civil contempt of court for your refusal to testify and says, “this person has stated publicly that they’re never going to comply, they’re never going to testify, they have continued to not comply or testify. And you holding them in jail or prison, during this grand jury for their refusal to testify, has gone from this civil form of contempt, to something that’s now illegal, because you’re actually holding them in jail knowing that that’s not going to be the coercive tool that you hope it will be, to get them to comply, and to testify before the grand jury.” And it’s not legal to hold someone in prison in that way, because they’ve never committed a crime, and then the state, the government, has crossed the line, right? They’ve crossed their own legal line.

That’s a strategy that’s worked well, but it does require that somebody sets up the infrastructure along with their comrades in the larger movement to support them. And that means being very, very public from the beginning of your situation, which is what happened with Steve the first time that he was subpoenaed to grand jury and what has happened with him the second time that he’s been subpoenaed.

TFSR: So just to belabor the point, because nobody actually said thisI don’t think. You both have mentioned going into the grand jury, and then refusing to speak and getting held in contempt. What happens if somebody invokes their fifth amendment? And why does that make this sort of proceeding so scary?

C: So when somebody goes in, and they’re asked a question by the prosecutor, the prosecutor is going to say something like, “Hey, what’s your name, state it for the record?” So I would say “My name is Chava so-and-so.” And then the prosecutor would ask me, “okay, tell me about what James had for lunch yesterday” and I would say, “you know, what, I’m gonna actually invoke my first, my fourth, my fifth, and any other applicable Amendment rights that I might have?” A prosecutor is gonna be like, “Oh, great. Okay, well, what did James have for lunch day before yesterday?”, I’d say “I’m going to invoke my first, my fourth, my fifth, and any other applicable Amendment rights”, and then eventually, the prosecutor is going to be very clear that that’s my entire plan, while I’m present in their grand jury room, and then they’re going to take me before judge, because they’re going to ask for me to be held in contempt. And then they’re likely to request from a judge that I be given immunity. And that immunity means that anything I say can’t necessarily be used against me. And that’s what the Fifth Amendment provides to us, is like protection from testifying things that would incriminate ourselves.

But what we don’t know is how our words then can be used against someone else, or how someone else’s words could be used against us. So it doesn’t protect us entirely, it just protects us in this very narrow way. And the court and the government call it being “granted” immunity, like there’s some fucking fairy godmother that’s coming and waving a wand and giving us this great gift. But it’s not a great gift. They’re actually imposing and forcing something on us, that strips us of our rights in that courtroom – are very limited rights – and takes them away from us. Because that’s the like beauty of the rights that the state has given us, right? They can give them they can take, and that’s all at their discretion.

So they impose immunity on you and you no longer – when you were taken in before the grand jury – can refuse to answer questions based off of your fifth amendment rights, right? And so then at that point, when you continue to refuse, you’d be taken back before a judge, who then would likely decide, “okay, well, we’re going to put you into coercive incarceration. So we’re going to try and compel this testimony out of you by incarcerating you”, and then things move from there. And that’s where we are right now with Steve, is at that point: immunity has been imposed upon him, he’s being held in contempt, and his contempt will be reviewed on a monthly basis by the judge in North Dakota.

TFSR: So you’ll have mentioned that Steve went before the grand jury in 2016. Steve was again called this year, I believe, before a grand jury and then released, is that correct? Like, where does Steve stand at the moment?

J: Right, so when Steve was subpoenaed in 2016 – his appearance date was actually in early 2017 – and he went and refused to testify. And the prosecutor never pursued contempt proceedings against him, they ended up withdrawing the subpoena, before he had to be found in contempt or be incarcerated or anything. When he appeared, when he first appeared in February, just about a month and a half ago, he again refused to cooperate and very quickly was taken before a federal magistrate judge, found in contempt and ordered into coercive custody for contempt. His legal team filed some motions and objections on the grounds that the magistrate judge actually did not have legal authority to find him in contempt or order him into custody. There’s some, you know, complicated and nuanced laws around that. Basically, he was ordered into jail by a judge that didn’t have authority to order him into jail.

And so his legal team filed some motions and objections and they were granted, and he was released from jail after 19 days of being unlawfully incarcerated. But before they released him from jail, they subpoenaed him again, to the same grand jury to appear on March 3. And when he appeared on March 3, and again refuse to cooperate, this time they brought in front of a federal district judge who did have authority to conduct contempt proceedings. And so at that point, he was again, found in contempt and ordered back into custody.

So I think this is a pretty salient example of just how ripe for abuse Grand Jury proceedings can be. That they can illegally incarcerate you for, you know, almost three weeks, and then the remedy for that is that you get released, but then you just get re-subpoenaed and taken back, and the whole thing starts again. And so, you know, the prosecution really gets…in some ways they get unlimited bites at the apple. I think we mentioned earlier that he can be incarcerated up to the length that this grand jury is impaneled, which is, you know, typically 18 months, but can be longer in some circumstances. But if that grand jury expires, there’s nothing that prevents the prosecutor from subpoena him to a subsequent grand jury. In this way, you know, we’ve seen, throughout history, that grand juries, there’s not a whole lot of check on this. And so they can really be used to harass and incapacitate activists and, you know, entire movement communities.

TFSR: So, how about earlier you had brought up the idea of SLAPP suits. Could you define that for the audience? And also, maybe, I don’t want to take this too far off a focus on Steve, but I’d like to recontextualize this, again, to be within not only supporting someone who has proven himself to be brave and an amazing supporter of other people involved in movement, but besides Morton County law enforcement trying to avoid or state officials trying to avoid possible lawsuits for the damages that they’ve caused to people. How does it relate to the timing right now the operation of DAPL

J: Well to speak to SLAPP suits and what they are, “SLAPP” is an acronym for “strategic lawsuit against public participation”. And it basically refers to lawsuits that…typically it’s large entities like corporations, sometimes governments, you know, powerful people filing against activists or journalists or sort of the little guy, for the purpose of basically retaliating against or silencing their damaging statement. So a lot of times this takes the form of defamation lawsuits, libel or slander. And so maybe a corporation sues this small activist group, and says these statements about us clubbing baby seals are defamatory, and they have to stop saying it and pay us damages. And, you know, a lot of the purpose of these lawsuits isn’t necessarily to win the lawsuit. Because of the power disparity, it’s often intended just to tie up the organization of the people in litigation. That if you’re a big corporation with, you know, billions and revenue and expenditures every year, it’s no big deal for you to spend a million dollars on, you know, a lawsuit. But if you’re a small, scrappy activist group, or citizen journalist or a whistleblower or something, you know, defending this humongous lawsuit can be can be totally debilitating.

And so there are statutes and a number of states that allow procedures to quickly dismiss these types of lawsuits. And that’s, I mean, kind of a whole other conversation. But I would, you know, if people are interested in this topic, the Civil Liberties Defense Center website has a number of resources about SLAPP suits, and defending against SLAPP suits, and things of that nature.

I can’t speak to the situation with DAPL, specifically, maybe Chava can, but I will say that we’re kind of in this moment where a lot of pipeline resistance efforts have seen some success. Recently, there was the pipeline that was supposed to run through Appalachia, they got cancelled. Resistance against line 3, in Minnesota has really been taking off. And so I think there is this sort of moment where, you know, people that are invested in these pipeline projects are seeing the success that resistance movements are having, and are looking for new ways to subvert those movements, undermine those movements and push back against those movements. And so I think, you know, it’s impossible to say like, if there’s a direct correlation between that and what’s going on with Steve’s case, but I do think it is sort of a reminder of what tools the state has against some of these movements, and how those movements should sort of think about making anti-repression and legal support and movement defense an integral part of their organizing throughout their campaigns.

C: I think one of the strategies that Energy Transfer Partners – which is like the larger company that was pursuing the Dakota Access Pipeline, along with many other pipeline related projects across North America – but Energy Transfer Partners goal with SLAPP suits, is not even necessarily to win. It’s a way of industry leveraging the law – in particular laws around RICO (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act), which a lot of people are have heard at least that term related to, like, “organized crime” type cases – but leveraging those laws as a way for industry to have a chilling effect on movements that are successful against them. And so Energy Transfer Partners kind of famously filed this outrageous SLAPP suit, including Greenpeace as one of the named parties that they were suing, and asking for, like, almost a billion dollars, I think in damages. Which, they knew they were never going to win that award of money in civil court. That wasn’t the point. The point was to make movements and NGOs, or nonprofit organizations that were supporting social movements against ETPs various pipeline projects, to make them have to scramble and exhaust their resources, both financially and as far as people power, real like human labor, to exhaust them to a point where you’re so focused on fighting the SLAPP suit, that you can’t be focused anymore on fighting the people who are suing you.

And that was dismissed in court because it was outrageous, right? But it doesn’t mean that it didn’t have some of its intended impact, which was to distract people’s energies towards this other thing. And ETP continues to do this. But we also know that pipelines are failing as financial projects. And it was known that the Dakota Access Pipeline was only ever going to be financially beneficial in the short term. It’s basically like a big scam to make a bunch of money at the at the beginning, and that it was going to be a financial failure in the long run. But their goal isn’t to make better energy for anybody if they were they would be pursuing other things. Their goal is to make money and at any cost possible, including the costs of human lives and the earth.

TFSR: So bringing it back to support for Steve, how can listeners support him? What are some good places that they can find out more information about his case? Does he need people to write to him? Are there any campaigns on going besides informing people about the resistance to the grand jury that people could join in on?

J: Absolutely. There’s a website supportstevemartinez.com, there’s an Instagram account @SupportSteveMartinez, and there’s a Twitter account SupportSteveNow. All of these are excellent ways to stay informed about what’s going on with Steve’s case, find out more information about grand juries about you know, anti-repression strategies, and to, you know, connect with what’s going on. Another really vital way to support Steve is to write to him. He really appreciates getting letters. And we know that regardless of what the government says about the nature of incarceration, we know that incarceration is always punitive. It’s always extremely damaging, and difficult, and writing letters and staying in contact with people in prison is an incredibly important and incredibly effective way of keeping them connected to their community, connected to their movement, keeping their time and their spirits occupied and lifted while they’re incarcerated. And so yeah, we definitely encourage people to write to Steve. You can find information – the address and sort of guidelines about what what kind of materials you can send – at his website, or on any of the social media accounts.

And also donations. Donations are being used to put in his commissary so that he can get snacks and food and, you know, hygiene items and things like that while he’s in jail. Also to be used for phone calls, so he can stay in contact with his partner, and other family. We know that calls from jail can be extraordinarily expensive. And then also supporting his partner and his family while he’s incarcerated. You know, they’ve lost Steve’s income since he’s now incarcerated. Bills don’t stop, expenses don’t stop, things like that. And so money to support the people around Steve while he’s standing up for his principles, and standing up for the movement, is incredibly important. Because, you know, grand jury resistance is a community effort, and it takes all of us to support the resistor and the resistor’s supporting all of us. And, yeah, it really takes a community in that way.

C: Yeah, I can’t really stress enough how vital people’s community support is. I think there are a lot of people who listen to this podcast that came and went from the camps at Standing Rock and the occupation there. And tens of thousands of people from all over the world did. And Steve is in prison to protect all of those people, at the end of the day. That’s the reality of the choice that he’s making. And so he’s showing some real solidarity to all of us who were present there and who fought against that pipeline, and for Indigenous sovereignty over the land and the water. But it’s our role to support him so that he can support us. And you know, James did mention that his partner is bearing a lot of the brunt. And that’s the reality of what’s happening, you know, anytime anyone is incarcerated: they are separated from their family and removed from their communities and are unable to fulfill the many obligations that they have to people that they love and they care about. There’s a GoFundMe page that’s gofundme.com/SupportSteveMartinez and that GoFundMe is going directly to support Steve, like James was saying, but also really to support his partner. They have a grandson, who is pretty little and I know that it’s really hard on Steve to be separated from his grandson. And that is something that brings a lot of joy to him, to even be able to talk to him on the phone and on a video chat. And so by people donating to that, it also enables Steve to video chat with his grandson and with his wife. And that’s a real lifeline for him right now.

The other thing that I would just say that people can do to support is be really public about your support. Even your banner drop that says, like, you know, “FREE STEVE MARTINEZ”, and “FUCK A GRAND JURY”, or like whatever you want to put on a banner, that’s actually proof, it’s evidence that can go into a motion to compel the court to release Steve. That there is a wide network of humans across the world, of comrades who support him and are enabling him to continue to stand against this grand jury. So if we show that he has that support, that’s also something that can be utilized in like a legal maneuver to get him released from court to compel the judge to do that. So even if you think your banner jobs are silly and they don’t matter, they do matter! And it shows the federal government that that we have Steve’s back, and he is going to be able to continue to maintain his silence.

TFSR: I’d like to ask you all, if you have anything else that I didn’t ask about, that you want to mention while we’re on the phone?

J: I’ll just add that, you know, we’ve sort of tried to emphasize this again and again, but movement support means all of us. It takes all of us to take action, but it also takes all of us to support each other, and care for each other when things get difficult. And so, again, putting that at the forefront of our minds: when we’re organizing it’s not just about the day of action and the days leading up to it. It’s about the days and weeks and years after that, that we have to continue to support each other, continue to help people navigate these legal processes that drag on and on. And the more that we can anticipate that and prepare for that and account for that in our organizing, the more resilient we are when these things occur. And I know Chava and I are both extremely indebted to all of our elders and all the people who have come before us that have helped teach us these lessons and teach us this information and allowed us to share it with other people. And so everybody that’s that’s sort of tread this path before us we’re extremely grateful for.

C: Yeah, I think if people want to learn more about grand jury resistance there’s a lot of great resources online, but I would really encourage people to check out the Freedom Archives, and anything in there related to Puerto Rican independentista resistance to grand juries. Those movement elders really built the model that we see used today successfully against grand juries. And we really just wouldn’t be where we are now, in our ability to resist this particularly nefarious and fucked up tool of the state, if it hadn’t been for many movement elders from a lot of different communities, particularly in the 1970’s and into the early 80’s and their resistance in national liberation struggles.

And I think the last thing I want to say is just that people went up to Standing Rock to, well people went up there for a lot of different reasons, right? But at the heart of it was to protect land and water and to engage in either, like, your own Indigenous resistance or to support those who are Indigenous and their resistance. But ultimately it was about a movement for liberation, which is what social movements are about. And at the heart of those movements for liberation is a lot of like deep care and love for each other. And having lived in those camps for months and lived in a field in the middle of the winter in so-called North Dakota, I can tell you the only thing that keeps you up at night really is like the deep blue loving care of your comrades. And Steve is really continuing to exemplify that deep love and care for his comrades, and for the reasons that he he stayed at camp after he thought he was just dropping something off.

TFSR: James and Chava thank you so much for this conversation and for all the work that you do. We really appreciate it.

J: Thank you.

C: Thank you, for all the work you do.

TFSR: You do work. Shucks. *laughs*

C: *playful scolding tone* You do work!

*everyone laughs*