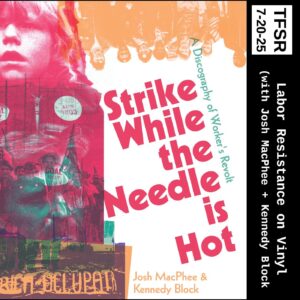

This week, we’re sharing a recent interview with Kennedy Block and Josh MacPhee, editors of Strike While The Needle Is Hot: A Discography of Workers Revolt from Common Notions. We speak about audio strike records, their role, what they tell us about the struggles they cover or were produced to amplify, and a bit about where music and popular resistance stand today.

Until the end of the month, the book is available from CommonNotions.org with a 15% discount if you check out using the code: strike15 .

Josh can be reached on instagram via @jmacphee or via email at josh@justseeds.org

They’re also both involved with Interference Archive (which produced audio of this collection of Stop Cop City communiques for their podcast, Audio Interference), and Josh is a co-founder of JustSeeds.Org, produces Signal Journal (he was interviewed by Ian for the show on the topic)

Free Jack, Free The Airwaves zine can be found here

. … . ..

Featured Tracks:

- Sciopero Interno by Fausto Amodei from Sciopero Interno, 1968, Italy [ 00:17:04 ]

- More Percent by Kirk Thorne from Songs from the NCU Strike, 1987, UK [ 00:36:11 ]

- A Year and a Bit by The Hindle Strikers with TBE from Part of the Union!, 1984 , UK[ 00:58:04 ]

- Viva La Huelga! by Polibio Mayorga from La Huelga, 1982, Ecuador [ 01:18:12 ]

. … . ..

Transcription

TFSR: We’re joined by the authors of Strike While the Needle is Hot: A Discography of Workers’ Revolt. Kennedy Block and Josh MacPhee, I wonder if you could introduce yourselves to the audience, sharing your names, pronouns, and any other information you’d like to share about yourselves?

Kennedy Block: Kennedy, it’s great to be here. Drop the [Stop Cop City] RICO prosecution!

Josh MacPhee: Hi, this is Josh MacPhee. I use he/him pronouns. This book is part of an ongoing process of about a decade of trying to dig into and explore political music. People can find some of that process in my last music-related book, An Encyclopedia of Political Record Labels, which is a materialist analysis of the production of records for political and social movements. In a way, Strike While the Needle is Hot is a deep dive into one of those platforms.

TFSR: When you say “a materialist approach,” could you go a little bit deeper, break that down a little bit?

Josh MacPhee: Kennedy is much more trained in school and in music than I am. I’m on the border of tone deaf…

Kennedy Block: This is true.

Josh MacPhee: So I am anything but an ethno-musicologist. I’m really looking at music as agitprop. The material structure around the music. I love vinyl records not just because they’re what I grew up listening to, and the thing that got me into punk and all these other things in the 80s, but because they come in a giant sleeve that is packed with all this extra information, and is like an oversized canvas for artwork. The material objectness of the sleeve, the material in it, where the record was pressed, how it was distributed, all of those things can tell us an immense amount about the people who are doing that, whether that’s a National Liberation Organization in Africa, or workers who are on a wildcat strike.

Kennedy Block: Yeah, I feel like it’s in the title, too. It’s like an encyclopedia of political record labels, of political songs, or musical styles. It’s this very specific piece…

Josh MacPhee: The discography of workers’ revolt. We’re really interested in how workers, in unions, but a lot of them relatively autonomously, were using this form of the vinyl record as a pretty powerful form of agitprop that wasn’t just about the songs. It was about using the songs beyond the picket line, because no one’s playing a record on the picket line. They’re just singing the songs, getting that out further. And the ways and tools that people do that, and what the benefits are of doing that.

TFSR: As you mentioned, you had this encyclopedia that you had worked on, Josh, and this new book, Strike While the Needle is Hot, talks about one of the aspects that you covered or touched on in the other one. I wonder if you both could talk a little bit about the archival work that you’ve engaged with, pulling together the book, and how you made the choices of what to include.

Kennedy Block: Yeah. I feel like I was thinking about this question. The best way to answer is on the top level, this book comes out of the shared archival principle that the best and perhaps only way to truly preserve something is to use it, to facilitate and to spread its use in one way or another. And so the book, in its presentation and what we focused on, is focused on recirculating as much of this material as possible. So a lot of that is [including] as many photos and stuff as we can, putting together the mixtape. But also tailoring the writing to pull out the bits and the anecdotes that all together help to open up our contemporary imagination of what is possible, and has invited us into continuing this as a style. I think the book tries to show it as part of a repertoire, and what’s being archived is this sense of what you can do and the possibilities there.

The top line that this comes out of it, the principle is that use is preserving something. I’m so dedicated that to Josh’s chagrin, I was circulating bootleg copies of our own book before it was out, on a printed out Google Doc. Just trying to get it instant ideas to as many people, particularly the kind of musicians I know, because they don’t know a lot of factory workers.

Josh MacPhee: I think that in the ideal world, the book would have come with a record, or a set of seven inches tucked into the sleeves. But unfortunately, we live under a capitalist copyright regime, and so there’s a funny thing where we can talk and write about these records, but we actually can’t reproduce the songs without clearing the rights. And the rights of most of this music are in a nether world, because the record label that put them out was ad hoc. The musicians are unlisted, so there’s no way to get the rights to most of this material. It sets up this funny thing where there’s an archival project about music in which there’s no actual music. Although, Kennedy mentioned it, we just finished a mixtape that we’re duping onto cassette, because that generally flies under the radar, and we’ll have a digital download too, so people can listen to a lot of the music. I don’t know if almost any of it is on platforms like Spotify, and very little of it is on YouTube. So it is hard to hear, because these are literally the records that fell through the cracks.

TFSR: You were kind enough to point me to some of the tracks. So hopefully listeners will hear a little bit of that interspersed in this conversation. I was just listening to it beforehand, and going back through the book, finding this is on page 122, and this one’s on whatever.

Have these things come across your awareness because of the work on the encyclopedia? Or have you requested these records from friends in the archiving community or the radical art community, ‘Hey, have you heard of any of these sorts of albums? Could you send them our way?’ How did you find the material that’s in the book?

Josh MacPhee: It was a mix. I had passively absorbed some of these records while I was collecting, just kind of hoovering up political records. And then my friend Chris, who was one of the founders of 56A – one of the last anarchist info shops in London, sadly, he out-of-the-blue mailed me this seven-inch record of Ford workers in the early 80s on strike in London. It’s an incredible record for several reasons. I’m pretty sure I sent you one of the tracks, “Johnny Striker,” and at the time, there was no evidence of this record online. It wasn’t on Discogs, which is the go-to site that catalogs music recordings. It wasn’t on eBay. It just didn’t exist. And so I was like, “Huh, this is really interesting. These workers who created their own autonomous workers’ organization outside of the Union, and then used some of that power during a strike to produce a record of all things.”

That had me digging through my existing collection and finding other examples that I hadn’t really correlated together yet, and made me think this is something worth digging deeper into and exploring. That started the hunt, sending notes out to friends who were in Scandinavia or other places, saying, “Hey, do you know any of these records that came out of strikes?” And then just digging. Digging online, digging in record stores, trying to find anything that looked like it could be one of these records. And then sometimes it was a flop.

A lot of times, there are interesting records, and a lot of them are interesting politically, sonically not so much. Some of them are really cool, but some of them… You know, how many times can you listen to the Internationale being sung by a chorus of people that aren’t trained singers? They’re not highly prized, so they’re not records that are expensive to get; they’re just hard to find because people aren’t promoting them. So they’ve just kind of fallen by the wayside.

-1;16;12

TFSR: Did you create the idea of a “strike record” in the putting together of this book? Or was this a pre-existing phenomenon where people were going into a labor struggle, and they were like, “Who’s going to make the strike record?” And what sort of materials were going into some of the records that you found here? You listed off a few different types of content, like speeches or workers’ choirs.

Kennedy Block: I could say a little bit to this. Correct me, if you feel this is wrong, Josh. It feels like these different concepts of what is a strike record, on one hand, it seems to exist as a practice. It’s a thing that, through the given ecosystem of leftist focus on culture that is maybe going 70 to 80 years after the salt on it, unions had record labels, these political organizations had record labels, as you documented in the encyclopedia.

But at the same time, we also make a distinction by only focusing on vinyl records. This is another slice that pushes us in the organizational and infrastructural direction. Because a vinyl record, as opposed to a cassette tape, for example, requires so much more coordination and organization to get off the ground, and commitment to a kind of scale that you don’t need to have with a small run of personally produced cassettes and things like this. That ends up getting reflected in the content of the records.

And I feel to me at least, what emerges after having worked on all these is the idea that a strike record is, at base, a form of active participation in a struggle like others, but it tends to focus on popularization, clarification of political stakes, and circulation. So it’s a form of agitprop. But at base, what we see in these records is people eschewing the distinction between protagonist and musician supporter and either just getting into the thick of it, playing on the picket lines, or producing different musical styles that attempt to fuse it and try to build these different kinds of music, sometimes a little harshly, like smash Welsh choir with industrial music or something.

Strike records end up being, on one hand, a technique of struggle, like others, that focuses on a particular range, but that is also not reducible to the music contained on the record. A strike record is not a certain kind, like diddy or an already known song like “the Internationale”. It’s also the collectives that produce it, the artist, the label that press the record, and the Community Studio that recorded it. And it’s the working class history and initiative of workers and musicians who are actually making the music.

Josh MacPhee: We catalog 80 records in the book, and we tried to focus on and set some boundaries. The vast majority of these records are records that were produced in part with workers’ input or on their behalf, during or directly after a strike. So they’re records of strikes, not records about strikes. There are some exceptions to that that we included, for different reasons, it doesn’t really maybe matter here, but largely we were trying to say that these are records that are of the strike. It’s not a record that’s like, “Let’s write a song about a strike that happened 100 years ago and have a pop hit about it,” however unlikely that would be. In our organizational system, that wouldn’t be a strike record.

What’s interesting is that you do see the development of a self-consciousness in some ways, about these records, but only in certain contexts. For instance, Belgium is a relatively small country in Europe that, at least in the United States, often gets forgotten about. And yet they’re heavily over-represented in this book, in part because of the group of musicians who call themselves GAM, Groupe d’Action Musicale (excuse my pronunciation of all languages, including English). They started in the early 70s, coming out of the left, coming out of social movements, working with workers to produce records out of strikes, and that sets the template. I think we include three of the records that they produced, and I’m pretty sure there are probably two or three more that we couldn’t get our hands on. We even had someone in Belgium who was hunting for us and found evidence of these other records, but just couldn’t get them. So they set this template.

And then we see that there are all of these other records that follow in the wake of that, and groups that style themselves in some ways, like GAM. There’s a group called Expression that produces a couple of records with striking workers. So you see that the strike record, at least in Belgium, becomes a thing that people are conscious of and seems desirous to produce, as opposed to Germany, which is a significantly larger country with a lot more workers, where there are a couple of records, but there’s not a lineage of them in the same way.

In Italy, you have a lot of strike records, but they don’t seem to be consciously thought of as separate from the records that come out of other social struggles. Italy, from the hot autumn of ’69 throughout the 1970s, is this roiling bed of struggle, and so you have hundreds of political records that are coming out of Italy. Some of them are about strikes, some of them are about housing occupations, and some of them are about militants who have been imprisoned, and there doesn’t seem to be any distinction between them. So there are a lot of strike records, but they’re not seen as being elevated above other militant records.

I think that the place of the strike record is really contingent on the locale. In the English-speaking world, the place where we get a self-consciousness around strike records is in England in ’84-’85 with the miners’ strike, where dozens of records come out. We’ve collected, I don’t know how many, 20 in the book, and my guess is there’s another dozen that slip through the cracks. There is a real consciousness in the UK, from that point forward, around the record as a tool within labor struggles.

TFSR: I wonder how much that relates to the conception of labor and organizing labor in a distinct organism, distinct trade union structure, versus the autonomous movement that was about breaking those boundaries. So the record in this case is just a reflection of the general social struggle. I’m basically just saying the same thing that you just said, maybe. That’s interesting, though. The autonomous movements–I see what you’re getting at.

You talked about GAM as a sort of house band for the trade union movement. Could you talk a bit about the performers? Your introduction mentions Joe Glaser appearing on numerous records that you came across. I wonder if you have thoughts about who participated in these albums, how many were professionals, who took up the task for a specific strike, how many were the workers themselves, and what sort of motivations you were able to uncover?

Josh MacPhee: Joe Glaser is interesting because he’s not actually on any of the strike records. He’s kind of this mercenary that, I’m assuming, was in the CP, the Communist Party in the 40s and 50s, and emerges in the 50s as the sort of troubadour for the labor movement. So he records upwards of a dozen records for different unions, where he writes the theme song for the UAW, United Auto Workers, and then the theme song for the longshoremen. And then he records these records that are a mixture of songs that he writes new lyrics to, classic labor songs that are fairly corny, and specific to the union. So these aren’t struggle records. These are the kind of records that you would get handed out at the National Conference of the Steel Workers, like “The Glorious History of the Steel Workers in Song.” And these are not autonomous records at all.

Interestingly, he’s this figure that’s associated with labor so profoundly within the music world. He doesn’t touch these strike records. It’s just not his world. And that’s where the strike records are really interesting, because they show this tension between the unions, particularly the unions that have developed intense and tacit negotiation agreements with management to smooth over industrial militancy versus the more insurgent unions and the wildcat workers that produce a lot more of the records. The unions are producing these hagiographic records. The workers are producing these “F**k the bosses” records, and they’re very different.

Kennedy Block: In terms of literal performers, the stuff that’s collected in the book is oftentimes just the workers themselves singing. Sometimes it’s the workers performing–like on one of my favorite tracks–with the local high school band. Sometimes it’s these relatively avant-garde musicians mixing it all up. And sometimes it’s also established musicians from a kind of pop-ish mold lending their name.

Josh, you have this story about the guy who gets blacklisted after making his 70s funk record about coal mining. It’s not like you have to give something up to make a record like this into a more legitimate thing, but I think the ones that we were attracted to, yeah, definitely. And you can hear it in the music, oftentimes, it comes from a pretty strong impulse or clarity or just life. So, despite the corniness, they can still be very beautiful.

Josh MacPhee: You can see that who the performer is in these records, evolves over time. It’s not like something on your path; it sort of bounces around. If, just for the sake of argument, we would split into pre-1980 and post-1980. Pre-1980, you’re much more likely to put a record on and find that it’s the workers themselves, or a union choir, or the music comes out of, is embedded in the community that the workers come out of. And what it says is, one: that workers recording and hearing themselves is meaningful to them, and two: that that community is large enough to support the production of 500 or 1000 of these little black discs that then have to get distributed in the world.

In the late 70s and early 80s, you see this transition happen, where increasingly, although never explicit, there is a question about, “Do we need to start producing songs in a more pop idiom to get a broader audience?” That’s when you start to see more external musicians come in. You start to see this breaking down, or breaking up of the community that would all share a song. And as that starts to disappear because of encroachments of capitalist entertainment industry in part, as well as just assaults on labor in general, you get more and more records where you basically have pop songs that are either often relatively poorly done by the workers, or by hired out people that are supporting the workers that do these songs, that are rock songs, or electro, pop rap.

A real change happens, and I think that the reasons for that are not entirely readable from the records themselves. I think we can infer that there is this kind of combination of the breaking down of the ties that hold the working class community together, so that the sort of folk idiom and working class song culture in which people teach their kids songs, and then they teach their kids songs, and so when you put those on a record everyone knows the songs, and it validates you, that starts to have less meaning because kids don’t want to learn those songs. They wanna learn the Beatles or whatever. And so then you start to get these songs that sound more like the Beatles, to varying effects.

Then there is this interesting period, and you really see it in Belgium, like we mentioned, where you have these militant musicians who really align themselves with the workers, and they record with the workers. They write the songs with the workers. They’re not writing songs about the strike. They’re really embedding themselves in the culture of the strike.

In some of the records, they actually write and talk about that, which is really interesting. The sort of affective sense of what it means to be a musician and part of this movement, and the need to involve workers, the need for workers to be able to be musicians as well. This real attempt to recognize that social struggle is about the transformation of both the individual and the community. So they really get to this transition point where it’s the strongest, this real interrogation of who is the performer. This is the most interesting moment: when that’s a question, not an answer.

TFSR: Thank you. That was a very good answer. I really appreciate that. I’ve been thinking a lot myself over the last few years about political folk music and its reproducibility. I’ve been learning acoustic guitar, for instance, just because I’ve been inspired throughout my life by political folk music and the idea that someone can just know the general tune, and might go and perform it with some friends in a slightly different way than how it’s recorded somewhere. But that moment where people share that song, share those lyrics, share the sentiments that are there, and make it their own, in that moment, it’s not the same as turning on Spotify and putting on a Beatles song. It’s not calling back to you out of history as this frozen moment of art. It’s mutable and alive in the moment. And, yeah, that’s a really cool insight about that shift towards pop culture.

Kennedy Block: One more aspect of that that comes through in the records is something that you’ve talked about before, Josh, that a lot of what we’re seeing involves, in some way, an invitation. It could be as simple as the fact that with many these records, the lyrics and the lead sheet, the chords to the songs are included, such that it’s being circulated within an audience that is also not being asked or trained to think of themselves as a passive, consuming audience.

TFSR: I guess you’ve kind of already gone into this a bit, but I’m curious about who the record was produced for. You’ve already talked about this in a few ways, but if we could just talk a little more specifically. How were the albums distributed? How much fundraising would come from these for the movement, for the strike? Did they get played on the radio during the struggles, or were they more souvenirs and “records of the moment and the struggle”?

Josh MacPhee: Some of that is not knowable by the records themselves, although some of the records give accounting of how many records were pressed and the expectation of the income that they’ll make. “We’ve prepaid this much into the strike fund,” so we have a little bit of information, but some of it is relatively unknowable. We do know that it’s unlikely any of these records were pressed in a volume less than 500 copies, because, as Kennedy was saying, unlike cassettes or CDs, you couldn’t at the time self-press a record. They had to be industrially produced. So there had to be a level of investment to make that happen.

I would say 75% of the records in the book are seven inches, as opposed to LPs. And I think that the reason for that and it makes a lot of sense–is that strikes are often quite short. There are limited resources, so it’s much easier to not only have the capital to put out a seven-inch but to record the 12 minutes that you can fit on a seven-inch versus the 40 minutes that you can fit on a 45 LP. The LPs are actually often quite extraordinary, because they speak to a much higher level of investment.

Kennedy Block: It’s easy to forget that the strikes are lasting a month, three months. To put together all of that in a couple of months, even just for a seven-inch, is incredible in the pace that people are working at. And it’s probably evidence of the familiarity and sort of see that.

Josh MacPhee: It shows how one of the unintended side effects of being on strike is that you have a lot more time.

Josh MacPhee: In the UK, the Ford record that we mentioned before says in really small type on the edge of the sleeve: “Will John Peel play this?” At least a couple of other records make this reference. John Peel was famous as one of the only DJs who played popular music on the BBC, and was sort of a make-or-break DJ for popular music acts in the UK. So there is a kind of consciousness around the possibility of getting radio play, I do think. Particularly when we’re talking about places like the UK, where there’s a really robust independent music scene, and you get records coming out in the 80s in support of things like the miners’ strike, like Billy Bragg or Test Department, one of these industrial bands, the Redskins. You have these bands whose songs were probably played on the radio.

But then you also have evidence on the record that Kennedy mentioned, which is from the early 70s. It’s like the first British miners’ strike record that we could find by John and City Lights, where John is this guy, John Paul Jones, who had a handful of hit pop records and was largely a stand-up musician, who’s a comedian, but he felt very strongly about the miners’ strike in 1972. He recorded the seven-inch that his label, Polydor, was going to put out, but they refused to put it out, and then it got banned from the radio. He sort of disappeared after that. His career was tanked. His backing band, City Lights, went on to become the relatively popular kind of blues-rock band, 10cc, so it didn’t hurt their career, but they also weren’t listed.

So you get different relationships to popularity. In Scandinavia, there were a number of quite popular groups that fell under the umbrella term called Prog, prog rock. The origin of the term is similar, in a way, but “progressive” in the Scandinavian context didn’t just mean progressive musically, but explicitly meant progressive politically. So you had folk bands that were playing much more complex progressive music increasingly, that also were explicitly leftists. Some of these bands ended up being extremely popular, and they would record strike records in support of workers, and those more than likely got played on the radio, because some of these bands were the equivalent of platinum-selling if they had been Western Anglophone bands.

Kennedy Block: Another aspect of the popularization that is aimed at by some of these records, not just in terms of popularization, in terms of audience cultivating, but also [effort] to popularize a struggle amongst the working class, to go and off through face to face interaction, create the sense that your fight is my fight, my fight is your fight.

For example, another, I think Belgium record, the Capsuleries Vivra! which is again an instance of a record that’s supported by another kind of leftist institution, this radical magazine (POUR). That’s the recording of a band that comes out of the factory, but they’re really tight. They play extremely well together, and they have some great songs. What’s documented on the sleeve is their travels to different factories to perform directly, acting as a cultural unit that can bridge struggles to other places. You know, in the same way that bands can do this, other kinds of political cultural units can do this, like soccer teams, maybe.

TFSR: Can you talk about how the tradition continues despite changes in the technology of sharing music? For instance, I’ve seen benefit compilations for social and ecological struggles like Stop Cop City, the Mountain Valley Pipeline, Anti Fascist Action, or prisoner support movements over the years. How has it changed since the days that you were recording in this book?

Josh MacPhee: The book goes up to about 1990, and part of the reason why we stopped there is because that’s the point at which cassettes and CDs start to outsell vinyl records. You don’t get strike records after that, because the whole point of the strike record is, on some level, to popularize a struggle. And so if people are listening to cassettes and CDs, then why would you put a vinyl record out? There isn’t the kind of nostalgia within the workers for the vinyl record, like there is in the punk scene, for instance.

First, you see a shift to cassettes and then to CDs. And both are much easier to produce. You can make 10 cassettes and just give them to workers on the picket line as a kind of morale booster. We didn’t dig that deep into these further technical iterations, because they’re much harder to track, and because of their potential boutiqueness. It’s hard to know whether one cassette was made or 10,000, and therefore it just didn’t seem worth tracking down and documenting a cassette that five copies were made just for the workers themselves, because that wasn’t what the project was about. Then that holds over to CDs.

Then we move into a lot of what you’re talking about, these compilations that show up on Bandcamp that you can pay a sliding scale of $10 to $30 to get this massive download of songs that people donated in support of these struggles. I think that those things are very cool, but one of the things that they often don’t have is any of this architecture around them to educate anyone about those struggles. Because it’s just ones and zeros, it’s just data that you pull down on your computer or your phone, and then it gets sucked up into algorithmic playlists that you have on whatever device, it kind of gets de-tethered from the struggle.

A lot of times, the songs aren’t about the struggle. They’re just donated to try to get people to buy, which is good. It’s important that people have ways and reasons to support these struggles, but there’s less of that kind of sense of a whole package. We can’t go backwards, but I look forward to people trying to go forwards and think of new ways to create music and sounds to support struggles that have context embedded in them, in ways that. When you listen, they have an it-ness that connects you to the politics, rather than just this ethereal relationship.

Kennedy Block: I think for me, when I try to look at contemporary iterations of this book, I think of the struggle against Cop City, mainly because it’s a struggle in which there was a sort of mastery of autonomous crews that were working to push the struggle forward. What seems the most interesting part, and what the struggle offered, was that these people took on the political responsibility of communicating the struggle and of creating. We did an exhibition of interference, and something that came out is the vast amount of, in this instance, writing. The vast number of attempts to popularize and to communicate the meaning and the needs of this struggle, and to take responsibility for that in zines and writing.

Also, treating the mainstream media as a terrain that you can make operations on, not making an ethical judgment about it, being for or against it, but treating it as part of this field that, as someone legitimately trying to form narratives and bring people in, it’s a terrain that you do things on. Things like we see in this book popped up. You have independent organs for the struggle, like Atlantic Community Press Collective, that start doing research that supports other kinds of efforts.

It’s a situation in which there’s the free giving away of authority to anyone interested in participating in the struggle, mainly through the technique of just non-condemnation. There’s this active tone of “you are a political actor, you have the authority to organize in your zone towards this.” And it helps create this ecosystem that feels, to me, the most akin to what we see in the book, what we’re interested in the book, that allows for all these kinds of experiments to happen. Part of the kernel, what I would take from the book and keep moving forward, and how I want to think about music moving forward, is this investment of agency and authority for anyone involved to start working on it. So there’s stuff like that.

But also within the Cop City struggle, there have been organized attempts to use music as a tool to get people involved. The most famous example was the series of raves and then music festivals inside the occupation as part of a place-making strategy. A strategy of building participation in the movement that had, I think, severe limitations that I don’t really know how to speak to properly. A lot of my thinking about this is influenced by a variety of things, but also, if you go into freejack.co, this is the support website for Jack Mazurek, who’s facing some charges after a series of home raids.

There’s a zine there you can download called “Free Jack, free the airways,” that works through this idea of what it is to be a militant musician. They’re not just defining music as something you do to support a struggle, but if we understand our struggles contemporarily as paradigmatic struggles between a world of death and a world of life your ability to freely develop your expression, and even just to literally make noise in public is attacked and impeached upon through a variety of legal [measures] and forcibly. And so they’re like, ‘”ou already have a stake in the struggle.” There’s good writing on that.

We include in full a flyer from the fifth Week of Action in the forest that was circulated during this music festival that I’m talking about. I kind of want to, if possible, just read it and then maybe Josh or Bursts, if you have thoughts about how this sketches something that’s actually pretty different than what we’re talking about, or whatever. It’ll probably take a minute or two. Is that okay?

“This is not a music festival because we are not here as consumers or as near spectators. This is not another photo op, another networking opportunity. We are here because our need for a free forest, culture, and existence can’t be crushed by the police, nor can it be sold back to us as an image in an uninspired Hollywood rip-off.

In a cave called Divje Babe, located in present-day Slovenia, archaeologists have recently discovered a 60,000-year-old flute. The human need for music has been with us since the very beginning. We are here to affirm that this deep and timeless desire, which has survived an ice age, the rise of empires and states, the advent of borders, slavery, war, famine, and holocausts, is an important part of the current struggle.

This movement is not just about a piece of land. It is not being fought between the police and their goons on one hand and some activists and their friends on the other. We are witnessing the collision of two competing ideas of life and the future. If they win, they will pollute all the rivers, destroy all the forests, pave over everything beautiful, and they will use the police to assure unlimited profits as our civilization chokes out its dying breaths. If we win, human needs will be measured against the imagination, against our collective ambitions and dreams, not held hostage by a system of artificial scarcity and waste. Our communities will not be held together by their ability to kill and maim enemies or heretics. They will be held together by music and the ability to generate common luxuries.

So let’s not say, ‘Oh, they don’t really care about the struggle. They are only here for the party’ or ‘This is not about music and festivals and all of this crap. This is about serious politics and organizing.’ Instead, let’s say the truth. This is only a glimpse of what we could give one another if we managed to outlive the oil-based economies of the current world system, the emancipation of the senses, the free development of the imagination, and the passions. This is precisely what we are fighting for.”

TFSR: Then the “No-Cop City, No Hollywood Dystopia.” It’s interesting. I sometimes forget that they were also planning a movie studio on the spot, in addition to the Cop City facility. Josh, I’m not sure if you’d like to reflect on that.

Josh MacPhee Let me go back a second. I grew up and was politicized through punk, like a lot of my peers. Within that paradigm, punk was presented as the inverse of, or the antagonis to to folk music, and so I had no experience listening to, understanding, or even really knowing what folk music was until relatively recently. It wasn’t until I started working on the encyclopedia, and in particular, had movement elders give me records and listen to them, that I realized that folk music means people’s music. Folk is not Joan Baez, there are folk traditions all over the world. They sound extremely diverse. They’re not all the same, although they can overlap. That has sent me down this rabbit hole of being extremely interested in folk music, this idea of how it feels to be in a community in which music is just part of that community. It’s just part of who you are and what you do. You all know songs, and you sing them together. We’ve fundamentally lost that for the most part.

What’s nice about the political angle within the Stop Cop-City struggle is this attempt to figure out how to reclaim that. That’s going to be harder to do than we would think. We’re so polluted/enamored by pop music. It’s also interesting because when you were reading that flyer, Kennedy, I was thinking about Glastonbury. How Glastonbury–he huge Music Festival in the UK–which started as a free festival that was made by people who just traveled around and squatted the land and then played these massive concerts with Hawkwind and all of these jammy, space rock bands. They were hyper political and now they are super corporate. Yet you have these people like Kneecap or Bob Vylan, who in some ways embody the very thing that flyer is against. Again just them speaking up about Palestine has led to them being banned from countries and facing criminal charges.

It’s interesting that we live in an ecosystem in which music is a powerful terrain of struggle, and there are lots of ways to struggle on that terrain. I really like this idea of trying to create these autonomous, very DIY music projects. But I also don’t want to stop the Kneecaps of the world from using a platform that they have to say things. I don’t think that’s the world we want to live in, where there are famous people, and we listen to them, and what they say makes it more important than if someone else says it. But whether we want to live in that world or not, it is the world we live in. It’s interesting if there’s a way to somehow do that and undo it at the same time.

I think that in the records around the miners’ strike in the mid-80s in the UK, you see that tension. You see people like Paul Weller from the Jam and Style Council. He created this super group called the Council Collective to record this record, to raise money for striking miners. And it’s a dance record. It’s made to be played on the radio and in the club. You can see this long-format apologia on the back. These musicians want to support the struggle, but they function at a level in which there’s so many people that need to sign off on what they do to get a record to come out, that when this record finally comes out, on the back there’s this longform apology about the fact that some striking miners dropped a cinder block off an overpass and hit a cab that was carrying scabs to the workplace, and people were injured. It’s almost embarrassing, this wanting to support struggle, but not the way that workers are actually struggling. They want to support some idealized version of how workers are going to struggle, in which everything is clean and simple and no one gets hurt.

We need to figure out ways to start to unpack that, to encourage the Kneecaps, but also hold accountability to it. It is not the musician’s role to decide how workers are going to struggle, or how Palestinians are going to struggle, or how people organizing against Cop City are going to struggle, and like that flyer says, invite as many people in as possible. If some massive pop star wants to support Cop City, then that’s great, but they don’t get to decide what that struggle looks like. It’s great because these records embody some of that tension, these early attempts at trying to hash that out and figure out how to do that.

Kennedy Block: One thing that seems to help in all these instances, the priority here is that there is action happening, that people are struggling and doing things. That, with all these strike records, the basis is that there is a strike going on, like in Cop City,

Josh MacPhee: There’s something at stake, something very real,

Kennedy Block: We learn that in the development of these cultural and political ecosystems, some of the values that one can take are that leading with bold action is one of your strongest friends. The struggle against Cop City started simultaneously with an info night. It was a public preempting of the city’s narrative of how this facility was going to be constructed. It was in the park and had most people, and then that night, the construction of equipment was burned.

Or in the George Floyd uprisings in 2020, within the first week, extremely soon, a police precinct was burned to the ground. Strong action, bond action, experiments create ecosystems around them. Action begets organization, almost more so sometimes than organization begets action. So we have that, and then a basic principle of not approaching struggle as a primarily ethical problem, as a place in which one should find and police bounds of purity, whether that’s your ideology or the mode of struggle. This one’s perhaps the sloppiest and the one the most about non-condemnation, everybody’s just going for it. That one is really hard in practice, but as a set of principles of unity and stuff like this, this is the direction that is supporting the most dynamic ecosystems of militant struggle that we’ve seen in the past five years, at least, probably more. And music, I don’t know. I’ve already spoken a lot about it.

TFSR: Getting back to the book and the way that you curated it. Obviously, you had a bigger volume of records to pick through, I’m sure, than you put in here because it was curated. Were there any records in particular that struck you as notable, the performers, the art, or the content of the album, or the inserts that you were able to find?

Josh MacPhee: One of the big ones which Kennedy mentioned in passing is this record by the Hindle Pickets in TBE, which was produced in the Midlands in the UK, just before the miners’ strike. Hindle Pickets are pickets from the Hindle Gear factory. It’s a workers’ choir that is a tradition in the UK, they work at this gear factory, I believe it’s in Bradford. TBE was, from what we can tell, a high school band; some of them may be the kids of the workers. They never released anything else, and there’s nothing specific about the band other than the musicians’ names in the record. But it’s this incredible mash-up of these young kids that are listening to a lot of Wire, Gang of Four, and the Buzzcocks. It’s this very post-punk kind of sound. And then these guys, who are just a workers’ choir, put out this song, ?Year and a Bit,” which is a droney post punk backbeat, with the workers narrating effectively, what it feels like to be on strike. And it’s extremely arresting.

It’s a pretty incredible record, both politically and as a pop record. That one is really a standout. In addition, it’s one of those records that’s just jam-packed with little pieces of paper. It’s got a whole sheet about how they produce the record. And then it’s got a letter from Neil Kinnock who’s the head of the National Union of Miners at the time, or he’s maybe the Labour Party liaison with the unions in support of the strike. Then there’s a history of the strike and why they went out on strike, and ways to support, and it’s really chock full of information. It’s one of these great things where you’re not just listening to this great record, but learning in almost minutia about the history of this struggle, and that’s a real standout. In a way, it is very similar to the Ford record that we mentioned, which is another record that is embedded with all this paratextual information so that you can really learn about the strike. Those are two really good examples. I don’t know if you want to throw a couple more in.

Kennedy Block: We’ve been sitting with them for a while now. In making the mix-tape, I was particularly surprised by how much some of the picket line ditties stuck in my head. So this is just the women’s choir of the Keresley Pit, just in most block-headed English tone: vocalizing “You won’t find us at the kitchen sink. You won’t find us at home. Come on over to the picket line, we’ll be picketing there.” I can’t get it out now. It’s effective for what it was attempting to do, being a means of hanging out together. I know that also, just doing this book, has made other elements of my life stick out to me more.

Recently, I had the pleasure of being involved in what they were calling a Morale. Some comrades had come back from Rojava with all these intense ideas about culture and development of struggle, and things like that. They helped to facilitate this night of revolutionary music, which is nothing I’ve ever experienced before, but that was immediately so easy to do. In a barn, with some straw on the ground, some twinkle lights, and people singing sort of IRA songs, everybody starts stamping to them and hooting and hollering. I don’t think I would have had as much of a way to get into, ingest, and care about it and to feel wrapped up in this music. It’s a kind of reinforcement. I found myself having more and more fun coming back to the records.

Josh MacPhee: Yeah. Maybe it’s worth mentioning that there’s this really interesting record we found. It’s the last record in the book. It’s from 1990 and it was put out by a union called Sitek, which is from Curaçao. It’s a country that I don’t know a ton about but Curaçao has a very complex linguistic mix because of a history of colonization, and it’s a full LP that is documenting a 1990 Union gathering. Also, there’s a big strike that happens at the same time, and it’s unclear whether they just go on strike every year, so maybe this is one of many records documenting their strikes. The record, although it lists tracks, is not tracked. So, people who are familiar with vinyl records: it’s just one long song, one long audio track that completely seamlessly intersperses field recordings out on the street, meetings, people giving speeches. And then, there’s this amazing moment in the record where this call and response starts up, where someone breaks from a speech into this chant that is the most incredible, poly-rhythmic calling response.

Kennedy Block: It’s not like “Free, Free Palestine, Free Palestine.” It’s like, “da-dah da-da-dah-da-ha.”

Josh MacPhee: Within it’s all a cappella. It’s incredible. That record is a real standout, even though we’re still trying to parse exactly what’s going on on it, because it switches from multiple languages without any contextual clues. That’s a really interesting and fascinating record.

Another great record is one of a couple that came out of the struggle in the Lip factory. Lip was a watch company. The watches were built on the border between France and Switzerland, classic watch territory, with a long history of anarchist watchmakers. In part, in response to May ’68, the culture of the workers really changed in the late 60s and early 1970s. In the early 1970s, the workers not only went on strike, but also occupied the factory and kidnapped some of the bosses. And there’s this record that they self-produce where they have this militant chanson singer Claire Martin Michone, who on the record is just listed as Claire, who is present for and listens to and takes notes during all their meetings and writes songs based on their meeting notes.

This record, these songs are maybe the only record ever that has songs about meetings interspersed with workers talking. Then she takes this show on the road and travels around France, giving concerts and selling watches from the occupied watch factory to support the workers. This is pretty incredible. It’s not just a piece of plastic. It’s a document of a very dense social process and struggle. The record is a seven-inch, but it’s in this oversize sleeve that unfolds and has cartoons in it, and all the information about the strike. It’s pretty great.

Kennedy Block: The slogan of a lot of this stuff could be: “It just keeps going.” It just keeps going, it just keeps folding into new activity. That’s the ethos of it. I was thinking of another conversation recently, that the ethos of an organization should not be to preserve itself, but to go for broke, and in the process, probably dissolve itself and become new things. And that feels like it happens over and over again in the process of these records. Going for broke. What that means is to preserve an underlying activity and culture, perhaps more so even than just this or that band.

Josh MacPhee: Many of the records are about a specific strike, but they document a sediment of struggle. It’s about a specific set of demands or a strike, but you can see that all these other people and struggles participated in the construction of that. There’s this another incredible record that was put out by the strikers at Chausson, which is a French bus manufacturer. They work with this group Germinale, which is a youthful seeming jazz rock act that actually writes a manifesto in the seven inch about what it means as musicians to participate in the struggle. They record a song that’s specifically about this strike, and that’s on one side of the record, but the other side of the record is a field recording of the picket line. The Chausson factory workers, in part, go out on strike for a set of reasons and conditions. The thing that pushes them or breaks the camel’s back, so to speak, is that the bosses lock them out. So they create this massive picket to stop the bosses from allowing the chassis of the buses to leave the factory; they’re basically blocking the bosses from running the factory without them, and they can’t do that themselves because there are not enough workers.

There’s another strike going on in Lyon at the time: the cable makers, who are mostly Moroccan, and they come to support the strikers. So there are these French-born lorry chassis makers, and then you have the Moroccan workers who come. The French strikers have a big band, a classic workers band, and then the Moroccan musicians come with all these North African instruments. The record is the six and a half, seven minute jam on the picket line of them playing together, and it’s incredible. It just shows the levels of solidarity that get embedded in these struggles that you wouldn’t know about if this record that shows and documents that struggle wasn’t still there to be picked up. The cover of the record is a screen-printed, rainbow-rolled, very graphic image. There’s no way it would exist if there hadn’t been the student and worker strikes in 1968, so it’s clearly drawing on that struggle as well. You can see how these histories of struggles intertwine to make these moments of militancy. These records are the objects that are windows into that.

Kennedy Block: The bit that you were referencing was written on the sleeve. They describe what you described in the last paragraph: “The party will last all day, referencing the face-off with the riot police. The first side of the disc recorded on site captures one of the most enthusiastic moments. Thanks to the contact established during the strike. In particular, with comments from the strike committee, we created a song which tells the story on the B-side: ‘Long live the Chausson strike!’ As for us and as much as possible, in liaison with other cultural groups, we intend to continue this type of work, minus errors and inadequacies, where the people live, work, struggle and express themselves, so that a culture will be created which belongs to them and bears witness to their multiple battles against the economic, political and cultural pressures…”

TFSR: That’s beautiful. Long live the strike. That’s really fascinating. When you were talking about that, that dug it a little deeper into me of how these aren’t just documentations of the moment or agitprop of the individual struggle that they’re documenting, or whatever. You can see the seeping in of what people are bringing, the culture, the demands, the desires that situate those specific struggles, too. That’s really interesting. That’s really cool.

Josh MacPhee: You see this interesting tension in the writing, and even in some of the music, where there’s people who are coming out of the communist traditions that have very didactic ways of articulating, communicating struggle, who are in these moments of profound social transformation, where the strike isn’t just about a higher wage, but it becomes about a new way of life. Where your dad’s didactic Communist Party way of communicating can’t contain the energies of the struggle in the community. That is interesting and exciting to see that stuff continually break down, that history being important, and people are drawing from it. They’re really trying to build something new and figuring it out by doing.

TFSR: You’ve already pointed to a few of the interesting labor struggles, like the watchmaking factory, for instance, or this cross-industry, cross-cultural solidarity that was being shown at the chassis-making factory. Were there any other labor struggles that you hadn’t heard about which piqued your interest, that you came across when you were researching for the book?

Kennedy Block: There is a lot. The only thing that’s just picking into my mind right now is this anecdote from the Gainer’s meat packing strike in Alberta, somewhere on Canada’s West Coast, that was very small, but with many different techniques. One of the techniques of their strike was also an organized boycott of Gainer’s meat, and that didn’t just mean “don’t buy it.” Workers and their families would go into grocery stores, put little stickers on the Gainer’s, meat in the store, saying ‘this is scab meat’, and then they would poke little holes in it. What does it actually mean to run a boycott? When you’re serious about it, and when you have an organized base that is actually in relationship to the product, not just saying: “Don’t buy it at the Home Depot.”

Josh MacPhee: It’s worth mentioning that there are several records that are not just about labor strikes, but clearly about feminist struggles. Particularly because we’re looking at the stuff in the 60s, 70s, and into the 80s, there’s a lot of miner struggles and these traditional conceptions of blue collar masculinity, but there’s a surprising number of records that came out of many more factories run by women.

There’s this great record from the Obsession factory in the mid-70s, which is a lingerie factory. All women’s garment workers went on strike, and they promoted the strike and the record by calling it the story of O’s. Obsession with the O being really big playing off of at the time, the soft porn story of O. It was a big movie that was in all the box offices across Europe, like a blockbuster film. So they’re playing off this question of sexuality and making lingerie to popularize their strike. There are a number of examples of these women’s struggles where there’s a real consciousness around feminist intervention into the realm of workers’ struggles.

Kennedy Block: There’s another one. When we looked at the punk record DOA, their seven-inch “General Strike,” is referencing something I had no idea happened, which was the development and near-pulling off of a General Strike in Canada in the early 80s. It urprised me with its breadth.

Josh MacPhee: It’s actually the only punk record in here that is being conceptualized as this paradigmatic political musical form. I think there’s something about the individualism rooted in it that probably made it difficult for punk bands to figure out a way to embed themselves in or to be close enough to strikes to really be able to participate in a meaningful way. It was surprising that this DOA record is literally the only punk record in the book, and that this record is also the only record that self-consciously advertises itself as a limited edition.

Kennedy Block: It came out afterwards that one of the main leaders of the solidarity coalition, who was tying up all these different sectors and pushing for political demands for this general strike, was on the picket so much that he got pneumonia. Then the person who replaced him sold everyone out in background deals essentially. That means that the strike basically ended as soon as this record came out. Also, the production timelines are pretty difficult, but it is funny that there’s this sense of trying to capitalize on it.

Josh MacPhee: At the exact same time that that record comes out, or maybe just a little bit before, there’s a general strike in Ecuador, and one of the most popular musicians in Ecuador, this guy, Polibio Mayorga who’s put out hundreds of records, produces a record called “La Huelga, Viva la Huelga.” It is an incredible cumbia song that supports the general strike, and it actually is so much more effective than the DOA. It is another thing in hindsight of looking back to my 16-year-old self, who was thinking that punk is the only politically real music, and how the sonic qualities of music are only as politically relevant as the way the music is used. It feels like the Huelga record is something that people all across Ecuador could bump and be super into, and the DOA record, a pretty small audience.

TFSR: Have you all seen the more recent documentary on Chumbawamba that came out recently? If you watch some of the documentaries that have come out about Chumbawamba’s early history, my understanding is that one of Chumbawamba’s early iterations was this project called Chimp Eats Banana. They were just putting together a benefit for the miners’ strike, and they were short on bands, so they’re asking themselves, what should they name the band? They picked up instruments, but didn’t play very well. They did eventually put out an album that’s pretty entertaining. If you can see footage of the punk bands performing at strike events, and you just see punks and Goths thrashing out on the stage, and the rest of the people are just wandering away during it. You can see that it absolutely is not speaking to the people that are actually participating in the labor element of it. Sorry to cut you off, Kennedy.

Kennedy Block: No, no, no. It’s funny. It reminds me of something. We watched one of the records, which seems to be from 1984 in the UK.

Josh MacPhee: It’s the same thing that Chumbawamba talked about, going onto the picket line and trying to figure out how to engage.

Kennedy Block: We were watching a documentary by Ken Loach called Which Side Are You On? And the cover looks exactly like the cover of a record that has “Which side are you on.”

Josh MacPhee: It’s essentially a soundtrack.

Kennedy Block: Again, it’s not phrased as a question. It is just, “Which side are you on”. That’s it. No question mark, no period, just like you already know. And there’s a recording in there of

Josh MacPhee: Charlie Livingston.

Kennedy Block: Charlie Livingston goes vocalizing: “Get off your knees, stand up and fight like our fathers did before.” It was within the aim presumably, it’s a room full of the most stone-faced people, but then it continues. One of those people in the audience gets up and performs a poem that they wrote, and they are more into it. I think one of our recordings also comes from that moment on the mixtape, that’s extremely raucous with fiddle sing-along that just keeps evolving into new songs.

Josh MacPhee: It acts like a striking hootenanny.

Kennedy Block: Yes, exactly. Seriously, for a minute and a half, they’re just going vocalizing: “Here we go, here we go, here we go.”

Josh MacPhee: Football chanting.

TFSR: Everyone loves to sing along.

Kennedy Block: Yeah.

Josh MacPhee: All there is to say is that the miners’ audience in ’84 was a tough audience for any musician, not just the floppy punk bands.

Kennedy Block: Yeah. But also, as you were saying, Josh, you have that anecdote about it, but if we’re taking it seriously, it is not necessarily the content of the music that creates its political impact. There’s the example of Pink Floyd’s “Another Brick in the Wall”, which, in our context, is perhaps a mostly fine, onboarding point to think about how stuff’s lbeig thought. But that in South Africa is banned, you can go to jail if you play that song.

Josh MacPhee: It became banned in South Africa because students who were going on strike were singing, “We don’t need your education, teacher.” They took the chorus as a chant, and so it led to being banned, which was, of course, not Pink Floyd’s intention. And so there’s that interesting thing in which, on some level, it’s the struggle that defines the meaning of the music, rather than the musician.

Kennedy Block: As something you think about as a designer within political spaces, too. You don’t get to just pick any old symbol, invest with all the meaning autonomously as an artist, and then, poof, there it is. We’re always working with a given language, and it’s defined by how it is used and the power that it accrues. The real effectiveness of political symbolism or music is what it can enforce as its meaning. Not just what you want it to be. This is kind of related, but do you know the Bible verse that said “And they put blood upon the lintel and upon the mantle, and God passed over them”, or whatever. I remember in 2020, in New York City, restaurants treated a handmade Black Lives Matter sign as blood on the lintel. So there was an enforcement of that slogan. It’s through action.

TFSR: As it should be. So you’ve already mentioned the mix tape idea. Should we talk about that if you’re worried about flying under the radar?

Josh MacPhee: No, that’s fine. We’re producing a small number of mixtapes, a couple hundred that have 24 tracks, 12 on each side that are mixed together, with edited versions of songs from the book. The actual physical cassette will be available soon. We are also going to link a digital download of that on the book page, on our publisher’s website, commonnotions.org, and we’ll also probably be on the justseeds.org website for the page for the book. So, if you’re an object fetishist, like I am, you’ll be able to get an actual cassette, and if you just want to hear the songs, you’ll be able to download the mixtape. And that’ll be if you go to commonnotions.org and search for “Strike While the Needle is Hot,” you can find it all on justseeds.org.

TFSR: I’ll link that for sure in the show notes for this. So any listeners, when this comes out, check that out. You were also mentioning a coupon code.

Josh MacPhee: Yes, for at least probably a week or two after this broadcast, so in the summer of 2025. If you go to commonnotions.org, buy the book and use the code at checkout, STRIKE15, you get 15% off the book.

TFSR: Josh and Kennedy, thanks so much for this conversation. Is there anything we didn’t touch on that comes to mind right now? Lingering albums?

Josh MacPhee: We went all over the place. If anyone listening knows of or has another strike record, get in touch. We’d love to hear about more. It’s always great to get feedback. So let us know what you think of the book, and let us know any ideas that you have. Both of us are really interested in trying to help facilitate ways that music and culture can be more impactful within our movements.

Kennedy Block: How can people best reach out? Instagram or email?

Josh MacPhee: Good question. I’m on Instagram. It’s @JMacphee, or email is josh@justseeds.org, and you can reach Kennedy through me, because he’s much more stealth in his communications than I am.

Kennedy Block: If you go to the corner of…

TFSR: At 2 o’clock in the morning,

Josh MacPhee: Bring a falafel.

Kennedy Block: The only other thing is that the RICO cases are starting up in Atlanta. Ayla King’s speedy trial just had its first meeting, and then was immediately delayed. It looks like the first set of trial groupings for our friends will begin. We’ve been given a gift. This is a point of concrete continuation and participation in one of the fiercest struggles of our era, and we owe it to our friends and to ourselves to shape the terrain that we will fight on in the next 20 years by fighting these cases. So make a plan to go to Atlanta. Organize your band to go to Atlanta, and organize your soccer group to go to Atlanta. Organize your queer line dancing group to go to Atlanta, make a carnival out of the cases and build connections. And also bring a tape recorder, because there are already punk bands playing outside of the courthouse. So let’s start putting it together.

Josh MacPhee: Similarly, we just saw the sanitation and city workers in Philadelphia forced to go back to work after being on strike for a number of weeks. I think we’re headed for a couple of hot years of labor unrest, and so support workers on strike in any way: go to the picket line and offer to help out. Get involved; if you’re in a union, start to mobilize your fellow workers to support other workers and use music. Get people coming out. Get that boom box out on the line.

Kennedy Block: If the city you’re in has another sanitation strike, be like Up Against the Wall Motherfucker, and pick up all that trash and bring it straight to the City Hall, or a rich neighborhood, and dump it there.

TFSR: It has to go somewhere, for sure.

Josh MacPhee: Build barricades.

TFSR: We are not promoting any illegal activity. That’s awesome. It’s just trash.

Kennedy Block: Recently in New York, people have thrown a bunch of trash in front of immigration vans, and trash alone is not enough to stop a speeding van from trying to ruin people’s lives.

Josh MacPhee: But in LA, we learned that burnt-out self-driving cars are enough to stop ICE vehicles.

Kennedy Block: It was the lesson from the Waymo blockade. That’s funny.

TFSR: Nail strips are a little more effective, but if they’re thrown in with your trash, then it’s the best of both worlds. Thank you so much, both of you, for being in conversation and for sharing this book. I really appreciate it.

Josh MacPhee: Thanks for having us.

TFSR: Yeah, go get a book, and I’ll be sure to link again to the Interference Archive podcast featuring some of those communiques from Cop City.

Josh MacPhee: Stop Cop City, awesome.