Making Links: June 11th, Long-term Prisoners, Anti-Repression Work

June 11th is the international day of solidarity with Marius Mason and all long-term anarchist prisoners. This year we want to explore the connections between long-term prisoner support and anti-repression efforts around recent uprisings, a sharp reminder to us that the difference between a status of imprisoned or not is often tenuous and temporary. With thousands of arrests for protesting, rioting, and property destruction from last summer’s George Floyd uprising, we must be preparing for the possibility that more of our friends and other rebels may end up in prison. We’re also seeking to find ways to facilitate interactions between our long-term prisoners and uprisings in the streets. We were happy to share the production of this episode with the lovely folks at June11.Org. To this end, we speak with:

- Cameron and Veera, who are part of a group that have been supporting prisoners from the Ferguson uprising for the last 7 years;

- Earthworm from Atlanta Solidarity Fund and ATL jail support ;

- Jeremy Hammond, formerly incarcerated anarchist and hacktivist, and his twin brother, Jason Hammond, who works with the Chicago Community Bond Fund. They produce the podcast, TwinTrouble

They share with us their experiences with state repression, what motivates them, and some thoughts on what we can be doing to make us, our communities, and our liberatory movements more resilient. The speakers responded to questions in the same order throughout the conversation but didn’t identify themselves much, so remember that the order and the projects they’re involved in can be found in our show notes.

You can learn more about Marius Mason and how to support him at SupportMariusMason.org. You can see past podcasts by June 11th, prisoner statements, artwork, info about the prisoners supported by the effort, a mix-tape they curated last year and events listed for various cities you can join at June11.org. We’re releasing this audio before June 11th to entice folks to consider a potluck, an action, a letter writing event, a banner drop, a postering rampage or something to share the day with folks behind walls. Hear our past June 11 episodes here.

You can also hear the June 11th statement for this year alongside other info on prisoner support from comrades at A-Radio Vienna in the May 2021 BadNews podcast!

Announcements

BRABC Letter Writing Today

If you’re in Asheville, join Blue Ridge Anarchist Black Cross today, June 6th for a letter writing from 5-7pm at West Asheville Park on Vermont Ave. BRABC meets every first Sunday at that time, provides info on prisoners with upcoming birthdays or facing repression, stationary, postage and company. Never written a letter? Don’t know how to start? Swing by and share some space!

Fundraising for Sean Swain Parole

Sean Swain is fighting to be paroled after 30 years in prison and 316 podcast segments. You can find more about how to support his efforts here: https://www.anarchistfederation.net/sean-swain-is-up-for-parole/

David Easley needs help

Comrade David Easley, A306400 at the Toledo Correctional Institution, who has in previous months been viciously assaulted by prison staff at the direction of the ToCI Warden Harold May, as well as number of other inmates also who have been isolated for torture and other oppressive, covert, and overt retaliatory actions at that facility, denied adequate medical care for speaking out against the cruel, inhumane treatment at that Ohio facility. More and more comrades are reporting occurring throughout the ODRC, and across this country for any who dare stand up and speak up for themselves, and the voiceless within the steel and concrete walls.

This is a CALL TO ACTION to zap the phone at the U.S. District Court in Toledo, Ohio and demand that Comrade David Easley be granted a phone conference with Judge James R. Knepp II, and the Attorney General because Comrade Easley’s lawyer of record has decided to go rogue by not filing a Memorandum Contra Motion as his client requested and now the State has presented a Motion to Dismiss his case to that court.

Plaintiff: David Easley, A306400

Case No: 3:18-CV-02050

Presiding Judge: James R. Knepp II

Courtroom Clerk: Jennifer Smith

Phone No: (419) 213-5571

Also, reach out to Comrade Easley using the contact info he like many of our would appreciate the concerns, and love from us on the outside to stay the course, and not get discouraged in his Daily Struggle.

David Easley #A306400

Toledo CI

PO Box 80033

Toledo, OH 43608

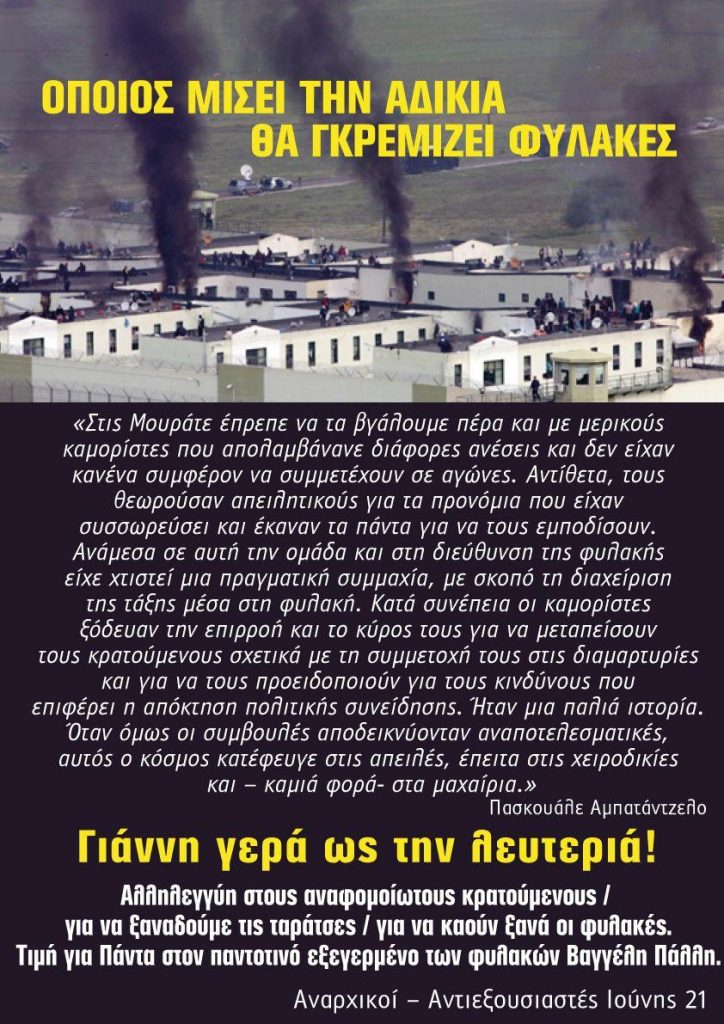

Anarchist Bank Robber and Prisoner, Giannis Dimitrakis Healing from Attack

the following was received from comrades at 1431 AM in Thessaloniki, Greece, a fellow member of the A-Radio Network. We had hoped to feature an interview they would facilitate with Giannis Dimitrakis for June 11th, however you’ll see why this hasn’t been possible. We hope he heals up quickly and would love to air that interview for the Week of Solidarity with Anarchist Prisoners in August:

On 24/5, our comrade, a political prisoner, the anarchist Giannis Dimitrakis was transported to the hospital of Lamia, seriously injured after the murderous attack he suffered in Domokou prison. G. Dimitrakis barely survived the the attack, and the blows he received caused multiple hematomas in the head, affecting basic functions of his brain. A necessary condition for the full recovery of the partner is the complete and continuous monitoring of him in a specialized rehabilitation center by specialist doctors and therapists.

In this crucial condition, the murderous bastards of the New Democracy government, M. Chrysochoidis, Sofia Nikolaou and their subordinates decide on Thursday June 3rd to transfer Giannis back to Domokos prison and even to a solitary confinement cell, supposedly for his health. Transferring our comrade there, with his brain functions in immediate danger, is for us a second attempt to kill him. Domokos prison does not meet in the slightest the conditions for the treatment and recovery of a prisoner in such a serious condition.

Αs a solidarity movement in general, we are again determined not to leave our comrade’s armor in their blood-stained hands. Nothing should be left unanswered, none of the people in charge of the ever-intensifying death policy that they unleash should be left out of our sights.

Immediate transfer of our partner to a specialized rehabilitation center

Hands down from political prisoners

Solidarity and strength to the anarchist fighter G. Dimitrakis

This is an invitation to engage June 11 in solidarity with Giannis Dimitrakis. On June 9th there will be a solidarity demo in Exarchia, Athens at 7pm!

. … . ..

Featured Tracks:

13 Blues for Thirteen Moons by Thee Silver Mt. Zion Memorial Orchestra & Tra-La-La Band from 13 Blues for Thirteen Moons

. … . ..

Transcription

Host 1: Would you please introduce yourselves and maybe who you are, what projects you’re working on and what experience you have with anti repression prisoner support work.

Cameron: My name is Cameron. I live in St. Louis. I’ve been doing prisoner support stuff for to varying degrees for the last 10 or so years. Having letter writing nights, fundraising for commissary stuff, sending in newsletters to jails and prisons.

Veera: I’m Veera. This is the biggest anti-repression prisoner support project that I’m a part of, or the longest running one. But similar to Cameron, I’ve been doing some support work for prisoners for probably the last 9 or 10 years, and have just maintained pen pals with several different prisoners across the states. And currently in southern Ontario, there are prisons, like across the region, that are on hunger strike, for different reasons, especially in regards to the pandemic and how they’ve been treated. And so I’ve been plugging into some of the hunger strike support work here. But yeah, also still getting acquainted with how projects are done here in this new place that I live.

Earthworm: Okay, my name is Earthworm from Atlanta, and I work with the Atlanta Solidarity Fund and the protester jail support team, and Cop Watch of East Atlanta. And we’ve got a lot of protester support experience because our friends have been getting arrested for years at different protests. So we turned it into something that has scaled way, way up, of course, particularly in the last year with the George Floyd uprisings.

Jeremy Hammond: Well, you know me, my name is Jeremy Hammond. I was recently released from federal prison several months ago. And I’ve been involved for most of my adult life. And since my release, I’ve just kind of been slowly getting my feet wet and seeing what my involvement would be most appropriate. And I’m also here with my brother-

Jason Hammond: Jason Hammond, that’s my voice right here. I’m his brother. And yeah, I’m a longtime supporter of Jeremy. But I’m also of course involved in on the ground protests related movements. One group that I’m a volunteer for is the Chicago Community Bond Fund. It’s a bond fund that has been involved in prison abolition struggles, most notably the George Floyd, Black Lives Matter uprising last year. We did a lot of work for political prisoners during these uprisings too.

Host 2: Can you tell us more about the role of your projects in uprising anti-repression, and some of the prisoners you’re supporting, or talk about examples of political coordination and action with other prisoners that might give the audience a sense of the agency of folks behind bars?

C: Well, I mean, in 2014, a group of us started supporting folks who got locked up during the Ferguson uprising, and it kind of came out of desire to not ignore, but actually just like, actively promote the reality that the folks that were participating were engaged in risky and creative and destructive actions, like looting, or shooting guns and arson. And we kept seeing a lot of people fall through the cracks in 2014, like in terms of getting support from like the, “movement”. So we just really wanted to make sure that folks got some kind of support. And so a lot of the people that were participating weren’t really like a part of a movement per se, like they weren’t like in an activist organization, or they weren’t organizers, they were kind of articulating themselves outside of that. And so we just felt like that was really important to see and acknowledge because, yeah, there were people that have gone away for, are now in prison for like five plus years, some people because of what they did.

And like there’s all sorts of narratives by nonprofits and activists, that the people who are like doing the heavier stuff were hurting the movement or kind of a part of a conspiracy of outsiders or criminals. And it felt like that kind of narrative was just reproducing the same that caused this moment, this uprising. This sort of demonization of people, this sort of keeping people in their place, ignoring the fact that people have agency and ability to like refuse to be victimized by systems that want to kill them or hurt them. And I’ve personally just felt like I was very frustrated to not see that narrative promoted or like accepted. That was kind of the big reason why I got involved in supporting folks.

To go back to like nonprofit stuff, like a lot of those folks weren’t really seeing what was happening right in front of them. This was an uprising that was extremely combative against not just the police, but also private property and with the authority of a lot of people who want to keep things the way they are. And people from all walks of life just coming to this situation, and like getting wrapped up in it, and like getting arrested, and like doing things that were dangerous, and not really talked about, and like a legible, easily palatable story. That was just a very hard thing to watch. Having gone through my own legal issues, through going through courts for years, and being arrested a bunch of times, and just like knowing how shitty that is to experience and how like grueling it is to go from one continuance to another. And I knew I had people who had my back, and people who would come to my court dates, and I just wanted to return that as well to other people.

V: Yeah, I can maybe just talk a little bit more about the specifics of the project that Cameron and I are a part of, as far as like the prisoners that we are supporting. They are just from a compilation of a list that we compiled from just mailing letters to people who got arrested during the Ferguson uprising. People from all walks of life and in that neighborhood, and not necessarily people that we could say that we were like politically aligned with, because it might even be safe to say that all of the people that we are supporting when we started supporting them wouldn’t necessarily have aligned themselves with any sort of politics.

Yeah, we sent letters and just said, basically, if they were willing to, we would put them on this public list — which is the list on AntistateSTL — put their images out there and their mailing addresses, and thereby making it easier for people across the country to support them. And so that list we’ve maintained, or someone has maintained, over the years. We had, I think 11 people at one point, and now it’s down to, oh gosh, like 5 or 6 maybe? Because people have gotten out just specifically from that list of folks, there’s two people that I spend a lot of time in communication with them and their families and have visited and everything. And one of them actually, Cameron was alluding to this, but you know, people would get arrested in Ferguson for doing a lot of what a lot of people were doing, which was looting and destruction of property and everything, and one of the guys that I support was arrested for those things and then because of priors, whenever he was sentenced, he actually got a sentence of 60 years. So he’s gonna be in for the rest of his life. So that’s like a very long term. In some ways that to me is like very mind blowing and it’s a very good example of the people that were acting in the streets weren’t always people that we were familiar with their lifestyle, or familiar with the risks that they were taking.

E: So we ran jail support for anybody that was arrested and were doing prisoner support for anybody who is stuck in jail, because they were denied bail or because they’re unfortunately, sent to prison. So we’ve provided all sorts of support for arrested folks.

Jeremy: All right, well, certainly my experience in prison, you have a wide variety of individuals who are locked up, many of which have become politicized in prison. And so they see someone who is locked up on a case such as mine with support from political movements on the outside people know that I’m an anarchist, and a prison abolition is right? And a lot of people are very curious about this. Right? Because of all the experiences in their own lives having been repressed by the criminal justice system.

As far as examples of coordination there’s unfortunately, like, prison they want to bury you, right? They want to prevent you from communicating to the outside world, to receive information of what’s going on in the outside world. And so the work that’s being done on the outside, such as everything from books to prisoners, to the support at people’s court dates and stuff, to having noise demonstrations outside the jail, really gets people who are curious about what’s going on. And so for an example, like I would regularly receive zines and newsletters from ABC and other organizations, right, which are very useful in discussing things that we would otherwise only have access to, like – say for example, something on the news, we would only receive information about what’s going on with the George Floyd uprising, the Michael Brown uprising, based on what was in the news, right? But now we have additional materials to share and discuss as a focus of discussions. For example newsletters from actual movement stuff itself.

And so when people see like the jail demonstrations outside the jail, when people see that there’s people attending each one of your court rooms, that they know that there’s kind of a camaraderie, a sense of loyalty and commitment to something. It kind of brings like prisoners together that we’re not just alone, that we’re, there’s a continuum of resistance, and each of our stories plays a part in that.

Jason: So this is Jason speaking right now, I can talk about my experiences with the Chicago Community bond fund. Just a little back history: this is a bond fund that was organized in response to the uprisings in Chicago against the Chicago police scandal, the murder of Laquan McDonald. There were a large movement, which included a number of arrests to protest the cover up of the murder. And so people had raised a good amount of money to bond out the resistors, the protesters, and in the wake of that it basically coalesced into a movement of an organization that tried to address you know, the problems of the prison system, the Cook County Jail, the mass incarceration project. It was an abolitionist project so we started just working with the community, bonding out people’s family, loved ones, friends, and all that, basically as much as we could try to empty the jail out. This was, I think, around like 2016.

Fast forward to the George Floyd uprising, the organization had been long a supporter of the BLM movement, and when this had happened the organization had definitely stepped up to do everything they possibly could within the organization, to not just bond out the protesters, and the activists but of course the larger community that was involved in, let’s say, property distribution, looting, breaking property, destruction. They stated clearly on that stance, which, in fact, BLM Chicago as well had made a stance to support people involved in the looting.

So we, every day, we’d be out bonding people from Cook County Jail. Sometimes, I personally would go up with a list of like 10 people in the jail, just bonding as many people as we possibly could, as well as trying to amplify and elevate the struggles of other organizations working to change the system. Yeah, this is one thing that’s Chicago Bond Fund had been doing in 2020. And we’re still doing it, you know. We also had a campaign to change the, basically end money bail type law in Illinois. It’s said it’s an “end money bail” but of course felonies and a little bit less palatable type charges, like violent charges or domestic charges, are not bailable, but these are details in the bond bill. But it’s still a pretty good bill the Pretrial Fairness Act, passed in Illinois because of our grassroots shit.

However, there’s still plenty of other challenges beyond the fact, about money for example, the campaign was “end money bail”, right? However, there’s all kinds of other, like compounding details that would allow a person to get what they call a “no bond”. For example, if they have two charges, they can be bond out for the first one, but for the second one in light of the fact that they were already on bond, they could have just be given what they call a “no bond” so that they’re still in there, no matter how expensive their bond is or depending on what kind of charges. So for that reason, there’s still tons of people currently in Cook County Jail and you know, we are expecting the numbers to go down as the the law rolls out, expecting to kind of be fully implemented in two years, but we are we are going to still see a number of people still in the Cook County jail system, even though they are pre trial, just because of all kinds of other laws that would prevent someone from leaving, you know. A large part of this country do not want to see the changes that we were fighting for be implemented. And you know, I mean, all you have to do is just kind of look at the rhetoric and what their actions are, they’re pushing back in the legal sense as well.

Yeah, there’s a major political battle basically between the far right, the John Catanzara FOP CPD camp, as well as the state’s attorney Kim Fox, Lori Lightfoot. Kim Fox has been actually a pretty vocal support of the end money bail project. So like there’s there’s a political battle, of course, as well.

TFRS: Have you seen your support work change over time? For instance the progression from supporting someone through their initial arrest and bonding out, to serving a prison sentence or doing other follow up work with them if that’s not the case. Or if you were in prison, how did your needs change over time from the initial court support and folks showing up and fundraising for lawyers during the initial phase to like, maybe follow up?

C: Well, I mean, initially, we found all these people’s names from like media articles, like there’s a website in Missouri where you can just like find all the court records of cases and so we just kind of like comb through all those and sent letters to them and stuff. And as folks started getting sentenced, some were incarcerated in prisons, other people were given time served because they’d been in jail the whole time and weren’t bailed out. So then the focus shifted from doing like court support, to like, just letter writing and some amount of fundraising when we could. So like just trying to fundraise for putting money on their books, or like maybe some of us have steady work or whatever, so we give $10-$20 a month to one person each at this point, if that’s where it’s at for the folks, at least for me, for the folks that are still locked up. And a few folks have been released in the last couple years. We kind of always tried to check in with them when they’re about to get released, like if they need anything, like, “here’s what we can offer”. It’s a pretty small group, we don’t, we’re not like an actual, like, organization, we just kind of run on our own capacity, but we try to help people when they get released a little bit. And I’ve maintained communication with at least one person pretty steadily who’s been released and we’re actually friends.

But yeah, basically, it’s been so long, I mean, 2014 is so long ago, and people who, a lot of these people like maybe they were in prison, and they got out…there was never an effort to convert somebody to like some political sway, or like political ideology. It was always just sort of like, you were a participant, and we would want the same if we were locked up. So because of that, like, a lot of times, there’s still a connection, but also people have their own lives. And they can move on or they like, have their struggles. I guess I bring that up, because yeah, just to sort of talk about the capacity that we have, as individuals, trying to do this and how we’re not a charity, we’re not a nonprofit or social workers. So we’re kind of trying to meet people where they’re at and have a more down to earth relationship. And if it leads to more of a friendship, then great, if it doesn’t, that’s not the point of it, or whatever.

V: I would, I would echo a lot of that. Honestly, like that progression, I guess, of what our support work looked like at times, I would even say was a bit awkward and clunky. Without this baseline of “we are anarchists” or “we are radicals and therefore we act it during this uprising”, I think it was a bit unclear for both the folks that were locked up and their support networks as to who we were, you know. We’re not social workers, we’re not like an activist organization with a bunch of money coming in, you know. We have a little website on noblogs.org. And we’re kind of you know, as far as this group is made up of now, I think there’s like two people left in St. Louis, who are still there and still active in it and the rest of us are, are all over.

So it’s rather like a disjointed and kind of a funny, awkward conversation to have at times where I’m talking to one of the guys that I support, his name is Alex and I had to have like several conversations with Alex’s mom to kind of like, get her to understand who I was, and that I wasn’t like someone who was going to help place her son in a job once he got out. I was just someone who was going to make sure that her son was looked after and not forgotten about and if something needed to happen where he needed his caseworker to be bothered about some piece of mail, or if he wasn’t getting shoes or something, then I was the person that was going to call and do that. And those sorts of things. I think that we had to be willing to kind of have those awkward conversations with people. And I think that for the most part, that’s been fine. You know, at worst, it’s awkward but we have been able to raise money and get people, when they get released, we’ve been able to give them phones and clothing and help them feel cared for in small ways. And I think that that’s a really important piece of what we do.

Host2: Earthworm, can you tell us about Atlanta?

E: I guess when we started doing jail support work, it was more on the fly in response to arrests happening. It was just kind of catch as catch can, you know. Somebody would be in jail and they’d need $4,000 to go to a bail bondsman to cover their $40,000 bail and we would need to come up with just by calling all our friends. Scrambling to put somebodys rent money up and hope that somebody could pay him back by the time rents due. And we realized in doing that, we needed a more organized, and we needed a bail fund. So in 2016, we started collecting money for that. And sometimes when people get arrested, it makes a lot of news and a bunch of donations roll in. And sometimes you’re able to even set some aside and have that for the next set of arrests. And of course, sometimes more expensive than the amount you bring in.

So we sort of struggled along through a whole series of different protests. And then in the George Floyd uprising, we were fortunate enough that we already were established. And we had that we had a website, and we had this long history of being able to bail out protesters, so we were sort of already a trusted group. And we were able to be really central in that effort and got way more donations than we were used to. But of course, also way more arrests than we’re used to. But with the donations, we were able to cover a lot more of the protesters’ needs. So whereas before, the money had just been very strictly for bail and hiring lawyers we’ve been able to do things like pay everybody’s fines and fees, and pay for medical costs and pay for other incidental things like a babysitter, if you need to go to court. Other things we would never have been able to afford before.

And the other thing that is very blessed that changed is we no longer have a cap to the amount of bail that we’re able to post, because before we had money, we didn’t want to blow it on one protesters. So if you were in there, on $40,000 bail or bond, we could only cover a portion of that, and then we would have to scramble to fundraise the rest of it.

So in the early stages, even before arrests happened when we hear about a protest getting set up. So that arrest might happen, we get the jail support team together and start scheduling who’s going to be available for the 36 hours after the protests if arrests go down. So we’ve got our phones people who have a physical cell phone, because that’s all you can call from jail, and they take turns carrying that and one phone person will bring it to the next person when their turn is over. We scheduled people to do arrestee tracking, which is finding out who’s been arrested, finding them in the jail system and keeping track of them to figure out when they are able to be bailed out, and then getting them bailed out and getting people to meet them they’re at the jail when they’re out. And then once they’re out, that is when court support takes over. And that’s everything from keeping track of when their court dates are and sending them reminders to finding lawyers and helping getting people there to their court dates, and whatever sort of support they need while their court cases going on. And then once their court case is over, there’s follow up hopefully they don’t go to prison or anything but there may be support to do as far as helping them if there’s going to be a civil lawsuit, helping them find lawyers for that, or helping them with whatever kind of evidence gathering or whatever support they need with that. Of course, they may have fines and fees to pay or like ankle monitor fees and that’s all stuff that fortunately now we’re able to afford.

Or unfortunately sometimes people go to prison. And then it’s time for prisoner support, which we do also to the people who are denied bail and they’re sitting in jail waiting for their trial to happen, of which we’ve got about eight in Atlanta. So that means writing the letters. And they also have the phone number so the same phone people who are doing the intake calls the night that people get arrested are also hearing from the long term prisoners, and just figuring out what support they need. Ideally, everybody who’s sitting in jail has their whole support crew of friends and family and whatever supporters, and those support crews can coordinate with each other and with the solidarity funds to make sure everybody’s getting what they need. Failing that, the jail support team just needs to act as a support crew for each prisoner. Meaning that the only number they’re calling is the jail support phone and the jail support phone people are communicating with the prisoner support people at large, who aren’t like the prisoner support for a particular individual and just saying you know, “so and so wants this kind of books can anybody volunteer to send them that” or “so and so is not receiving medical attention, and we need to get everybody we know to call the jail and pressure them to let him see a doctor”, and, and so on like that.

Host 2: Oh my gosh, it sounds like y’all really got that figured out *laughs sweetly*

E: *laughing* Well, I think it’s a process of figuring it out on an ongoing basis. I appreciate you saying that. But I definitely don’t think anybody feels like we haven’t figured.

Jeremy: This is Jeremy. So certainly the arrest and pretrial support work is very crucial. It’s very different than say post conviction, post sentencing. First, I think we just need to listen to the particular circumstances and needs of each person and their charge. But also recognize that since we’re talking about groups and waves of repression, all the circumstances are also linked. In particular, somebody who’s facing charges often can’t openly talk in detail about like, what they’re particularly being charged with. So I think it kind of does rely on support communities to kind of — it’s a political battle, because they want to, like build support for the individual, but also like, build support for the particular so called “crimes” that they’ve been accused of, if it’s like a direct action that they’re currently in prison for. So the way the public narrative goes the way of, in support of what the prosecution’s characterization of the crimes are, right. Like if say, some of the actions over the past couple years, and the uprisings involve various arsons, and property destruction. Well, I think it’s important these groups are doing support work, not just support the individual and whatever the particular legal strategy is, like, say they’re innocent, or whatever, but also support the actual crimes themselves. We had to legitimize the act itself to the public.

And then of course, post-conviction hopefully. I think it makes a difference the amount of time in the in the whole negotiation process, the charges, like the prosecutors are willing to offer up does make a difference if they believe that the person being prosecuted is in isolation, versus if they’re part of a movement, and the prosecutor strategy is also different, and then be more willing to make like better deals or make concessions, that would be a better outcome for the individual.

And then, of course, post-conviction & post-sentencing, you want to give a voice to someone who’s now freely able to speak. The other thing is, as the person’s time draws to a conclusion, and they’re about to be released, the needs also change. That you want to make sure that somebody has every opportunity to make it upon the release, especially long term prisoners, like their ease of adapting. And fortunately I can say that, like they’ve taken care of me throughout my entire bid. I have nothing but respect and admiration for the various groups that came out and supported me. And because of that, I had a pretty easy transition when I was released people came and picked me up from the jail, people were bringing me stuff at the halfway house. You know, my brother and friends made sure that I had a place to stay, you know.

So these types of things help ease the transition I mean, because otherwise, the state will just kick you out and basically hope that you fail again. And so it’s up to us to make sure that doesn’t happen.

Host 1: Yeah, and that, but on that point, it especially when a person’s been inside for decades — like a decade is a long fucking time — but if someone’s been in for 30 years, like the amount of change that’s occurred during that period of time, the amount of loss of loved ones…

Jeremy: Yeah, yeah, it’s truly shocking. Especially the cultural changes, the changes in the city. You know, people might not…everything is technology, people definitely have difficulty adapting to how people apply for jobs and people secure housing and stuff like that is all different now.

J11: So there have been 1000’s of people arrested during the George Floyd uprising last year, over 300 federal cases and innumerable state felony cases. So given your experience, what can we be doing now to prevent and prepare for those uprising defendants, some of them serving time in prison, Cameron and Veera?

C: To me? It feels kind of inevitable. Part of it feels hard to prevent people from acting – or not…that’s not the question, but like, prevent, repression feels hard because uprisings are often just sort of like, they’re super spontaneous and people like who don’t necessarily consider surveillance or security culture like maybe some of us do. Or anarchists or radicals do are going to get get caught up in like the repression and I guess ideally it would be a matter of trying to like, really push for people to like, be aware of, if like a surveillance camera can see you or be aware of like, the risk that you’re taking, but also like, in some ways, having that kind of, sort of awareness can actually kind of placate you. So it’s sort of a hard balance to figure out how to kind of prevent avoidable repression. Because yeah, people are going to do what they’re gonna do. And like, I think, at least having that baseline of that’s what’s gonna happen is like, where I start from.

V: I think it’s very hard to know how to talk about what prevention looks like. We have our experience, and especially having gone through Ferguson, and especially like the repression support work, post Ferguson, we can look at that and say, “okay, we know how bad this can get, so let’s keep this from happening”. But then how do you do that? Like, how do you like, make those connections in the moment.

I can remember a moment last summer, during one of the demos, the George Floyd demos that happened, and I was… So I was hyper aware of everyone that wouldn’t have their faces covered. And so I’m running around and I’m a white woman, who’s in my 30s, running around telling people to cover their faces, and they feel invincible in the moment they feel like, “nothing’s gonna stop me, nothing, no one’s stopping me right now. Like, what do I care?” And here I am running around, telling them all to cover their faces, and they’re looking at me, like, “no, get away from me, this isn’t your moment!” You know? And, and then like, some ways, it’s like yeah, that’s true. And, like, what am I gonna do? Am I gonna stop you and say, “Look, I know how this goes I know how this ends and start telling them…” the answer is no, I’m not gonna do that. But I think that is part of what we can do show up to these things with just bandanas to hand out, you know.

And as far as preparation, I don’t know, I thought about that. But I think that the model of what this support group is doing, find a small group of people — and we are, we’re a small group of people that are just willing to say, “Okay, these 11 people, we’re gonna make sure they’re taken care of.” And I think if you can form groups like that, and just kind of trust each other to do the bottom line for some of these people that are getting locked up, I think that that can be a really good start.

E: Number one thing, I think we need to be educating everybody that we can about not talking to police, and doing other security culture measures to keep ourselves from going to jail in the first place. You know, as far as educating people about wearing masks and security cameras, and just taking precautions, about things that could get somebody in trouble, not talking about illegal things that somebody could get in trouble for, not posting sketchy stuff on social media. Not talking to the cops, or anybody who might talk to the cops.

And when I say “not talking to the cops”, like not saying anything to the cops, other than “I’m going to remain silent, I want to see a lawyer, or am I being detained? Am I free to go?”, or “I don’t consent to a search”. And that is it, as far as what anybody should say to police. So I think holding trainings and holding them for as many people as we can, particularly because we’re getting lots of brand new people who aren’t used to being protesters is going to save a ton of money, countless hours, and misery in terms of people going to jail, and potentially prison later on. Because it’s so heartbreaking when you hear about somebody didn’t know that they shouldn’t talk to the cops, or they didn’t know that they had the right to not talk to cops, and they’ve just threw away what power they had to protect themselves.

Or I guess you could say, conversely, when we hear about people who did get that training, and did know to keep their mouth shut, and were able to tell their friends to keep their mouth shut, that prevents them from going to jail. And that is a huge relief. You know, when we hear from people, and they’re like, “Oh, no, I didn’t say anything to the cops! You think I’m crazy?”. That’s just like a choir of angels singing.

Jeremy: So first off, as with everything, it’s important that you think through your actions before you carry them out. And I think it’s also important to look at the history of cases and to see how people got caught and the mistakes people have made. So the way we don’t repeat the same mistakes so that way, we don’t keep this ongoing cycle of arrests and incarceration. We obviously want to reduce the numbers of people captured by the state.

Jason: This is Jason now. Yeah so obviously, “don’t get caught” is the ongoing lesson that we’re trying to learn. Secondly, we can’t forget, we have to keep the momentum up for people who are facing charges, we have to demand their charges be dropped in whatever form we can we can be writing letters, we could do petitions, we could be doing protests, we could be doing rallies, we could be doing letter writing parties, we could organize our own letter writing chapters, we could organize our own prisoner support chapters. So there’s all kinds of things that we could be doing and are doing to kind of keep the momentum up.

This is a pretty unique moment where you’re still in the wake of where the largest uprisings of many people’s lives, and there is a lot of energy ready to be harvested to kind of push the abolition our work forward, as well as change the system. So the people who are arrested trying to fight the power, to change the system, they really need to be supported if we agree with their goals. So let’s, let’s do everything we can to keep the momentum going on. And you know, people are exploring new ways of doing this.

Host 1: So one of the big things with long term prisoner support that June 11th is trying to address is not letting these people be forgotten. As interest in detention from last summer is already greatly decreased. what can we do to ensure energy and support lasts as long as the effects of the repression will.

C: For me it’s important to be like unapologetic about what people do, or for people to be like, “yes, people engaged in collective and individual actions that were incredibly threatening to the State and Capital and then they get caught”. So it’s like, it is being unapologetic about it is sort of giving people a sense of agency in their actions, as opposed to kind of seeing folks as they became, I mean, obviously, people became victims of state repression, but like, they were resisting, being repressed in day to day life, or oppressed in day to day life. And I guess just like putting it that way can help me kind of see the reality of it, and for lack of a better word, like humanize people.

For instance I think last summer, people were actually coming out in support of looting. Like, that wasn’t happening in 2014. That was a very hard position to hold. And I think it still is in a lot of circles today, but it was very exciting to me because it helps people see the people that are doing that, and create this sort of contagious effect of “Oh, people who are doing that are doing that for a variety of reasons and they deserve to be supported if they get arrested”, that deserves to be spread, and not just throw it under the rug. Because I think if you do that, then you lose the essence throwing the fact that there’s looting, throwing the fact that there’s lots of burning going on, the fact that there’s a fair amount of combative gunfire in the air, just all sorts of creative stuff going on sort of gives a lot of dimension to these uprisings. And I think people can see themselves better in that than they can see themselves in like a more civil disobedience sort of narrative that often just completely erases that. Just talking about it in that way and just like, again, just being unapologetic.

We want to build a different world or live in a different world and the way we get to that is dangerous, but also can be very empowering and exciting and incredibly worthwhile. And the more people who are unapologetic about it, who are like “I support all these combative actions”, the more to me it’s on people’s minds, and the less likely it can be swept under the rug.

V: Yeah, I think that’s the move that we see, or like this boundary pushing of an acceptable narrative. I think that we can participate in that as anarchists and as actors in these rebellious moments. I don’t always know how to push those narratives of the boundary shifting. You know, social media has never been my strong suit, but I think that there are ways to take it to social media and push those things. You know, as the nonviolent protesters and the police were the big bad and “we weren’t doing anything wrong” sort of thing, that’s when we saw some of the people that we supported sort of get forgotten, you know? And I think that that’s changed. That was different last summer, and that the repression support is going to look different because of that.

I think that’s great. I think that there’s still more work to do. And I think that we can be a part of that work. Again, I don’t always know how, I think having those conversations. Just from my personal example, I know that every one of my family was very confused about my participation and Ferguson stuff. Last summer, half of my family was in the streets after dark. And I think in part because of the conversations that we were having, and the ways that things started to be more acceptable, and more people were willing to confront this discomfort.

E: Wow, that is a tough one. I think that’s something that long term prisoners experienced widely, you know? You get a lot of support in the first couple years and then once you’re in there for a few years, the world keeps going and kind of starts to pass you by, and it’s just heartbreaking to think about people in there, wondering if anybody still cares about them. And you know, getting those letters that are just such a precious lifeline when you’re in there, and getting them less and less often. That’s got to be a desperate feeling. I think anybody who hasn’t experienced that, we probably don’t understand just how much of a lifeline that support from the outside is.

So I think trying to communicate that to people, and talk about prisoner support as a core antirepression effort. I think it often gets overlooked as sort of one of the unsexy grunt work things. And it’s kind of hard to write letters, there’s some social anxiety there, people don’t know what to say. But just getting that to be more of a core part of all of our efforts. It’s a mutual aid effort, because you and I, one day, are very likely to end up doing some time. You know, if we’re effective at what we’re trying to do and I hope we are, it’s extremely likely that they’re going to come after us. So setting up these efforts and promoting them as “this is an important part of the antirepression work that we do”, supporting prisoners could directly benefit us one day, and will definitely benefit our community.

So, and I think that there are a lot more opportunities to do prisoner support but it’s kind of overlooked as an activity. Because I frequently run into people who say “I don’t have a lot of consistent time but I’m able to do something here and there, what kind of work do you recommend?”, and I’m like “write a prisoner. You can do that on your own, you can do it kind of at work, or whenever you get a few minutes, it’s totally independent”. And it is such a lifeline for that person. And it’s a way to directly help, you know? Cuz there’s so much that we do that is kind of planting seeds for the future, or just hoping that one day it’ll bring about revolutionary change — which this, I think, again, is a big important piece of doing the prisoner support — but it also directly means so much to a specific individual, that you can see the difference that it makes.

So, talking to people who need guidance about how they can contribute, and who maybe want to work independently, maybe can’t leave the house, don’t have good transportation aren’t able to come to meetings, this is something that you can do from home, that you can do entirely by yourself. If you’re not able to risk arrest, or if you’re not able to physically keep up with a march, you can keep in touch with a prisoner, you can write them. If you hate writing letters you can get a JPay account and send emails, that’s a lot easier. You can put money on your phone account and let them call you. Or you can, some jails and prisons have the like video visits thing, you can do any of that. Once again, I don’t think we can even really understand how important it is for them to know that there’s somebody out there that they can count on, that they can reach out to if they’re in a desperate situation.

I think another big barrier to people’s willingness to begin writing a prisoner is uncertainty about how much time they can commit to it and not wanting to start off strong and then kind of leave the prisoner hanging, which is an important concern. But I would say you know, if you can only do one letter every six months, be upfront about that. But if you can only do one letter as a one time thing, just be truthful about that, and set the expectations realistic. And whatever you can do is incredibly meaningful.

Host 2: And for you, Jeremy?

Jeremy: Well, certainly the work that people have done with June 11th have brought attention to like anarchist and Earth Liberation prisoners who have experienced long amounts of time behind bars and they have not been forgotten and their stories aren’t over either. As far as the cycle of oppression and arrests and incarceration and how do we avoid burnout, and how do we ensure energy and stuff like that: I think one of the big things is we need to realize that we have the capability of winning. That this isn’t just an ongoing cycle that’s going to repeat forever. We believe that we will win, we believe that there is going to be a moment that we could overturn the system. Abolition is mainstream discourse now so we just need to keep the pressure up and keep it going and keep chipping away at the armor of the system.

Of course avoid arrests I mean as much as possible, and bring attention to the people who have unfortunately fell into the dragnet. But I think one of the other things I liked about the work that people have done around June 11th is that it kept people who are behind bars involved, to the extent possible. And really as someone who’s been behind bars and who has been following the June 11th stuff…we want to see people continue the work that we’ve been doing. Even though we might not have all the details, we don’t need to know all the details.

Jason: Yeah. So, I mean, there were 1000’s of arrests last year. It’s summertime now, they say that somewhat the interest has waned in protesting, people wanting to go back to normal, whatever, but I don’t see it that way. I see plenty of people still willing to take the fight. And so let’s get creative, let’s see what new kinds of things we could do. Let’s keep the struggle up, keep amplifying. Like my brother said we do believe we could win, and we do believe that we have made a lot of changes just within the last year. Let’s see how far we can take it.

Host 2: What could it look like to have more connection between long term political or politicized prisoners, and activity and resistance in the streets and elsewhere?

C: Part of my impetus for being involved in the Ferguson prisoner support group, or whatever, is just kind of trying to encourage a culture of solidarity. Especially in a way that tries to cross all sorts of cultural and subcultural divides, whether that be like racial or gender, or class, whatever. Just trying to see how we can fortunately, and unfortunately, have this moment where — especially during an uprising — we’re not following an easy script. Because day to day life is extremely segregated, it’s extremely…it can feel pretty isolating going through day to day life, going to work, going to school, raising your family, whatever. And being just in that baseline, and then whenever that kind of gets shook up a little bit, it’s an opportunity if you have a certain perspective to try to bridge, or break out of, that sort of stalemate.

I think with the prisoner support stuff, it’s always felt important to me to try to meet people where they’re at to have a variety of folks from all sorts of disparate or common situations and just have more perspective. And I love trying to foster situations or moments or being in moments where that is a little more uninhibited, or more relaxed. So like, how do you do that outside of these ideal — and they’re not even really ideal, there’s all sorts of terrible things that happen in uprisings as well, I don’t want to romanticize that if I can — but it is a thing where, yeah, it feels a little looser and easier. So like, how do you do that when it’s over? How do you foster a culture of solidarity of mutual aid that continues to break down like separations? I think we’re always between a rock and a hard place with this, but I think, especially in this case, writing folks, after the uprising ends, ideally, it can help create a sense that “Oh, if this happens to a friend, maybe I would do the same thing”.

Maybe they would have always done the same thing. Because obviously people have their own support networks. But like, maybe us doing that kind of helps spark an idea that like, “oh, if somebody is in trouble, or if somebody is having a hard time because of state repression or because of work, or all sorts of struggles, I can do something too. Or I can call these people who helped me in the past, and we can do something about it”.

So that’s the ideal that I have of doing this project, and even on a practical level, having more support inside and outside of prison walls and jails is helpful. Like if one of us happens to go to prison or jail, we might know somebody in there, somebody you connected with who’s like out, who is released who might be like, “Oh, yeah, I got a buddy in this jail or this prison that you’re going to and it might help you out”. Kind of not the most empowering thing, but it’s like, again, it’s like you’re between a rock and a hard place and these situations…or ultimately I want to like break out of having to think about that, but I think it’s a great place to start.

V: Yeah, it’s I feel similar to Cameron. There’s parts of this that just feel tough to answer, especially regarding the prisoner support work that we’re doing with people who I don’t know that they would identify as political prisoners. But maybe something that I have learned from this and from them is I was kind of talking about the awkwardness of making the connection at first, and then sort of allowing that to just be what it was. Like, “I’m here, and I know you because of this thing, because we were acting at the same time in the same place for a lot of the same reasons” and then sort of seeing where that takes us. And because these guys are not political prisoners, or “political prisoners“, it’s taken me and our relationship in all sorts of places. And I think that that’s been a beautiful way to connect. It’s opened up like my eyes to a lot of the different day to day oppression that some of these people have been living through, and that they’re sort of like allowing me to see into their life me as someone who they wouldn’t have allowed that, before all of this.

And I think that that’s been a really beautiful piece that’s come out of this, because we sort of open it up for connection to happen in all sorts of ways that don’t really hinge on “let’s read this radical text together and have a book club about it”, but it looks different. And then suddenly George Floyd uprising happened, and I’m getting emails and phone calls from them, where they’re just talking to me about how this is inspiring them from the inside and how they’re talking to people, their other inmates inside about why they acted in the way that they did and suddenly you see this fire again, and then you get to be inspired by that with them. And I think that a lot of that is because we allowed for a more open connection, and then we’re allowed to go down this path with them. I think our connection with these guys is a bit different but it’s still one that I continue to feel inspired by.

J11: How about you, Earthworm?

E: Again, I think staying in touch with people is the very ground level of that. Writing to those folks and for their advice and their input. Atlanta ABC runs a newsletter that we send out to probably about 250 prisoners, mostly in Georgia, but throughout the Southeast, that’s mostly written by them: they’ll receive the newsletter and we put a ask for contributions in it, and then they’ll mail us and we type it up and get it in the next newsletter. And staying in touch that way at least they’re connected in with what’s going on, they’re getting news about whatever the revolutionary struggles are, and they’re able to give their input. They’re able to lend support to people who are facing charges, who might go to prison, because they obviously have the clearest idea of how to handle that, and how to keep that in perspective, you know? If you’re facing a little bit of time, being in touch with someone who’s doing a lot of time can be very helpful.

We also publish prisoners writings on the Anarchist Black Cross website. And when they are engaging with something that’s going on in the moment, we’ll publish that more widely kind of spread that to other news sources to keep them engaged that way. I think the other part of that is to hear from them about what struggles are going on inside the prisons, and connect the people who are working on the outside to lend support to those things. So, if people are being brutalized in there, or there’s some horrible racist guard who’s harassing particular inmates, or behaving badly in general, we on the outside are able to bring pressure on that as a result of maintaining this connection with the long term prisoner. There are eyes and ears on the outside.

Jeremy: Certainly like the world we’re building is a world without prisons and we want everybody to be freed unconditionally, regardless of their particular circumstance. We support political prisoners and prisoners of war, but we also support politicized prisoners, we also support prisoners of everything, you know? So, often though, like the state will target political cases as like a canary in the coal mine type situations, where they use new legal techniques to go after political prisoners that, if successful, they’ll generalize. But the same works both ways too. They’ll also use tactics to target segments of the population that they think nobody will rush to defend either for that matter. And so it’s important that we’re fighting for all different types of cases and not letting the state get away with anything.

As far as encountering each other we need to keep up sending physical newsletters into the prisons, sending books to people in prison, doing radio shows on radio networks that have reach within prison, the jail demos and stuff like that. You would be very surprised at the long term reach that some of these actions happen. Like, for example, like when I was being transferred around a couple years ago with the grand jury Virginia thing, right? I ran into somebody at the Oklahoma Transfer Center, right? And I thought he looked familiar, right? Then he came over, said something like “I remember you and Jerry were at New York, they were always having demonstrations outside the jail for you all”. And I was like, “Wow, that was like eight years ago”. But you never know, like, something like that can stick in people’s minds. And I think that has an effect on the mentality of people that “you are not alone, you’re not fighting this alone”, and that June 11th specifically, like, if you are questioning whether you want to be involved in something – first off you should always think your actions through — but know that if you do get in trouble the movement will have your back, will see you through this whole thing, that you’re not alone.

Host 1: Are there any last things that y’all want to add, any ways that people can follow your work or get into contact with the folks that you support?

C: People can go to antistatestl.noblogs.org there’s a tab on the website that says “Ferguson Related Prisoners” and that list is up to date as to who’s still locked up and who still wants some kind of support. There’s also a PayPal link for commissary donations, or release fund donations. People are also welcome just to directly send it to the folks inside themselves if they prefer that.

E: So the Atlanta jail support efforts is not just Atlanta people, lots of work is remote. So if you want to help out with our jail support efforts, we’ve got a mountain of work that needs to be done and we’d be delighted to plug you in and get you trained up to do that. Of course, there’s probably a similar effort in your area that you can get involved in with probably a little bit of googling. If you want to write to any of our long term prisoners, atljailsupport.org has an email that you can reach out to us on and we will plug you in and get you connected to one of them. Also atlblackcross.org is for not specifically protest related prisoners, but all prisoners who are now protesting the conditions of their confinement or protesting the system in general. And if you visit that site there are ways to write to them as well.

Jeremy: Alright, first, I want to pay my respects to the comrades behind bars who are still enduring this repression, the folks who are facing charges now who might have a journey in front of them still. I want to say: we got your back, we support what you’re doing, stay strong.

As far as the work me and my brother are doing, you all know that we do a podcast called Twin Trouble, you could check us out at twintrouble.net. As you all might know, I have several conditions of supervised release, which involves stuff about association with civil disobedience and a few of the things that make my involvement and stuff post a release is going to be difficult to navigate these conditions. Nevertheless, the spirit of resistance is there. I’m currently finding ways to become involved in a way that’s meaningful and safe for both myself and others. But so yeah, check us out on the podcast twintrouble.net we got a few other projects in the works, but I just want to show my appreciation to everybody who has had both me and my brothers back up until this point and the future is unwritten. So who knows what might come next.