Stop The Mountain Valley Pipeline

The Mountain Valley Pipeline, or MVP is planned to be a 300 + mile pipeline 42 inches in diameter being built to transport compressed so-called Natural Gas from the Marcellus formation in the Appalachian Basin, from northern West Virginia to southern Virginia for export. The pipeline started being built in 2018 and is slated to cross over 1,000 waterways, posing a danger to countless human and non-human animals and plants along the way as well as being responsible for 19 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions, equivalent to 19 million passenger cars or 23 average U.S. coal fired power plants each year. It’s being built by a number of corporations involved in other fossil fuel infrastructure like ConEd & EQT. As of November 2020, the project was 3 years behind schedule and over $3 billion over budget because of a coalition of on-the-ground grassroots direct action and resistance, geographically dispersed solidarity actions and court challenges determined to keep this Marcellus Shale gas in the ground.

This week, we’ll speak with Toby and Emily, two longtime activists resisting the MVP’s construction about the pipeline, some of the resistance history, MVP’s attempt in federal court to intimidate and identify folks who run the social media accounts called “Appalachians Against Pipelines” and how to get involved in the struggle to fight climate change. You can find thorough coverage of the topic, and piss off the extraction industry, by following @AppalachiansAgainstPipelines on fedbook and instagram and the @StopTheMVP on twitter. You can support the ongoing resistance by throwing money at the effort’s fundraising page: bit.ly/supportmvpresistance.

You can find our past interviews about the MVP, including with folks actively in tree-sits and mono-pods at our website (by searching Mountain Valley Pipeline), and as well as our interviews about the water crisis in West Virginia generally and in WV prisons (by searching “Elk River”).

To learn more about the struggle at Line 3 and folks who are doing anti-repression work around it, check it this link and the related site: https://www.planline3.com/support-the-resistance

In about a week, you can a transcribed and easily printable version of this conversation for free at https://TFSR.WTF/Zines. You can follow us on social media and find our streaming platforms at TFSR.WTF/Links. You can support our transcription and publishing efforts monetarily, if you appreciate our work, by visiting patreon.com/TFSR or checking out other methods at TFSR.WTF/Support. And you can find more about our radio broadcasts, including how to get our free, weekly, hour-long broadcast up on a community station near you, by visiting TFSR.WTF/Radio.

Announcement

Eric King Trial Support

Antifascist, vegan and anarchist prisoner Eric King will be heading to trial soon and his support is inviting folks to show up at the Alfred A. Arraj Federal Courthouse in so-called Denver, CO, October 12-15th to support him. You can find filings on his behalf and background on the case at the Civil Liberties Defense Center at CLDC.org, and find updates on the case at SupportEricKing.Org, and the support Twitter and Instagram.

. … . ..

Featured Track:

- Elk River Blues performed by Rachel Eddy from Hand on the Plow

. … . ..

Transcription

TFSR: So if y’all would please introduce yourselves with whatever names, pronouns, location or why we are talking and what you’re involved in for the audience, that would be super helpful.

Emily: Cool. Yeah. My name is Emily, I’m joining us from so-called Virginia, in New River Valley area, pretty close to where the pipelines currently being built.

Toby: I’m Toby, my pronouns are they/them. I am also in so-called Virginia, pretty close to the New River Valley, and also very close to where the pipeline is currently being built.

TFSR: This pipeline that we’re talking about is the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP). And I’m wondering if you all could maybe tell us a bit about the plan of the MVP, what’s been built so far, the path that it is planned to take, what it will be carrying… just all the like logistical stuff about that, as it is up to this point. Maybe what the investment company behind it is called.

Toby: Yeah, totally. So Mountain Valley Pipeline, or MVP that we usually just call it is a 300-ish mile pipeline. It’s 42 inches in diameter, which is like a giant pipeline. That’s one of the biggest pipelines. It’s gonna transport compressed natural gas from the Marcellus formation in the Appalachian basin. And it’s gonna connect to an existing pipeline: The Transco pipeline. It runs from Northern West Virginia, all the way down through to Southwest Virginia. Then it’s gonna go 75 miles into North Carolina through its South Gate extension, which is still being decided in court. So, that’s going to go through like Rockingham County and Alamance County in North Carolina. When it is built, if it’s ever built (hopefully it’s never built), It would emit the 89.5 million metric tons of carbon. So that’s like 26 coal plants or 19 million passenger cars. It is right now being built by a company called Precision Pipeline, which is the same company that is building Line 3. The project itself is owned by EQT EQN Midstream who is based in Pittsburgh. And it’s like funded by like major banks who fund EQT EQN like JP Morgan, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, all the big name banks, and a lot of other banks. Emily, would you like to talk about maybe what they’ve built what they haven’t built?

Emily: Yeah, absolutely. They claim that they built a lot more, but it’s really only, like maybe 51% built. Some outside sources say, essentially, a ton of what they’re claiming to have built is not actually like completed to the point where gas could flow through it. But they have done a lot of work in pretty much most of Northern West Virginia, Pennsylvania and Franklin County in Virginia. But the vast majority of the pipeline’s water crossings are not done. And they have over 1000 water crossings that they will do over the course of the pipeline. Yeah, a lot of the work that’s going on is currently happening in Monroe County in West Virginia, and then Montgomery county and Giles County, in Virginia, and also in Roanoke County.

Toby: I think like they are claiming that like 92% of their work is done. But really what that means is they have done some work on 92% of the pipeline. But it’s really important to say that the work that they have yet to do is going to be some of their most difficult work. It’s going to be going over some of their steepest sections. It’s kind of hard to describe to people who aren’t from around here or who haven’t done a lot of hiking or spend a lot of time in these mountains. But when we say the steepest sections, we’re not talking about like “Oh, it’s a steep hill.” It’s like very few degrees off from a literal cliff that they’re going to try and build a pipeline through. And that includes trenching and grading and daisy chaining equipment down the hill so that they can actually do their work. Which is incredibly dangerous for themselves and for the environment around them.

Emily: Yeah, and they have already flipped excavators. I believe that one Precision Pipeline employee has already died because of their complete disregard for safety precautions or common sense perhaps.

Toby: Yeah, like they are building through karst terrain, which is really prone to landslides and sinkholes. And that mixed with the incredible steepness of the land around them and also the work that they’re doing producing lots of erosion. They are facing a lot of difficulties with their construction. They are three years behind schedule and $3 billion over budget. Some of that is $2.5 million in fines that they have occurred through over 250 water quality violations.

TFSR: So is that like they’ve caused erosion through their construction that’s leaked into water supplies to rivers outside of the scope of…. Is it called an ERC?

Toby: Yeah, those are what most of those violations are from. And a lot of that $3 billion over budget is the amount of work that you’ve had to do. That’s just sediment and erosion control. And they spend millions of dollars doing sediment and erosion control where if they were not building this pipeline, they would have not had to spend all that money.

Emily: It’s also important to note that most of those violations were recorded and tracked and submitted by a citizen watch group here. So that is this community being like “You are destroying our water, you are destroying our communities. We now have to go out every day and watch you do this destruction and take photographs of it, every time it rains.” There’s teams of people that go out along the path and observe and record what’s going on so that they can then submit that to the DEQ and try and get some sort of consequences for all this destruction. I think it’s really important to note that it’s not because the company is like doing anything. The company is leaving this all on the people who live in the path. All on the people who are fighting it. And the DEQ is also leaving that burden on us here

TFSR: Yeah, there’s not like Department of Environmental Quality workers out there, like you say, going up and down the path of the pipeline of what’s been built so far and testing.

Emily: They come out when they’re caught, right? And then they need proof, oftentimes, to be convinced.

TFSR: When it was quoted “19 million passenger cars” would be the footprint, is that like the the estimated amount of carbon produced by the lifespan of the pipeline and all that it’s like slated to carry through it? Or is that like a yearly thing? Or what? How is that figured?

Toby: Yeah, so that’s what they are predicting is going to be the annual emissions. So that’s like emissions from the combustion of the gas the pipeline would carry. That also comes from a predicted methane leaks across the gas supply chain, and emissions from the actual compression. Then also like the emissions from the gas extraction and processing that’s happening up in Northern West Virginia. So that’s not including the emissions that are currently happening from all the construction that’s going on. But the majority of that is the actual gas combustion. And then also 45% of that number is from the amount that this pipeline is going to leak. And just the standard leaking that all pipelines do.

I think because of the terrain that we’re in, and the amount of like ups and downs and also the fact that this pipeline has gone on for over three years that they scheduled for their construction, it means that it’s going to be way more susceptible to leaking, to explosions. Because if you think about it, the pipe in themselves, they are not rated to sit out in a field being exposed to the elements for three plus years. And that’s what certain sections of this pipeline have don. You drive by in this area, and you go by their pipe yards, and that pipe has been sitting there for years. It’s not rated to do that. The coating on it that’s supposed to protect it is not rated to withstand that amount of exposure. And they still are saying that it’s perfectly safe to put in the ground and to pressurize and put compressed natural gas through. They claim that they rotate every section of pipe that’s laying out every day. That’s what they claim. They don’t do that at all. But that’s what they claim that they’re doing to their shareholders and all the regulatory agencies.

TFSR: So besides the the weight of the methane leaks… All those other elements that you described along the 300 mile path, there’s also the what is the imminent threats to the viability of streams and waterways and aquifers that it’s traveling through. That would seem like that would also require constant vigilance of people in the communities along that 300 miles to be watching for breaks or for spills or for leaks just so that they’re not drinking poisoned water.

Toby: Totally. As Emily was saying there’s like over 1000 water crossings that they are going to do and that does not begin to describe the aquifers that it passes through and how many people along the route that get their drinking water from wells that would be impacted by spills and leaks. Karst terrain is a natural filter and a lot of people do have wells to those aquifers. If anything were to happen. If there was a break in the line or a leak then you are looking at people losing access to clean drinking water. And we’re in Appalachia, that’s not a new thing for people around here. That’s not a new occurrence. This region has a long history of being a sacrifice zone for the fossil fuel extractive industries and those industries poisoning their drinking water and their well water. So that’s not new. But that still doesn’t make it right.

Emily: Yeah. And I think something, also on that, is that it’s already happening, right? We’re talking about leaks and that’s totally a huge risk of this project. But just the construction itself, because of the geology of the area, because of the karst terrain, people have already lost water just from the construction. We know people whose wells have dried up and that can’t be undone. They just recently pierced a pretty big aquifer that feeds all of the families that live on an entire mountain. And they denied that they hit that aquifer. But because the water tables here are so complex… which is what leads to those sinkholes… Because it’s so complex if you hit the ground water there’s no way to know how far that impact will extend into the mountains.

TFSR: There was a couple of times back in…. I want to say 2012 and 2013… [correction, 2014] this show did interviews with folks that were doing water distribution around West Virginia, and around Virginia because there were two coal related spills. There was the Freedom Industries spill, where floodwaters had washed uncontained coal cleaning chemicals that were a private industry recipe. The company wouldn’t release what the actual chemicals that were involved in it to the state EPA in West Virginia but it was released into the water supply. And folks from around the region were going up and driving huge water buffaloes, huge tanks, driving pallets of water bottles down and up into hollers and into rural communities. Because if people are relying on these water supplies that are naturally occurring and they don’t have the infrastructure where they’ve got a local county or city government that’s actually filtering the water…. even if it could filter for some of these chemicals, and some of these toxins…

The phrase used, “sacrifice zone”, in Appalachia… this is a clear example in the last decade of when industry destroys people’s ability to drink water. I mean, people and that’s excluding all the other living beings that live off of these water supplies. I can’t imagine watching 300 miles worth of one of these pipelines and all the impacted communities who are going to be left. Not not only where poverty in some cases is endemic, but also the poverty is where people are lacking easy access to transportation, let alone going and finding another source of water. Poverty aside, that’s just going to be a huge problem for anyone, whatever their level of wealth is. With how isolated people live up in these mountains, it just seems like a really huge weight to put on. Just so that some corporations can extract the stuff that we already know is destroying the ability of humans to live comfortably on this planet.

Toby: Yeah, exactly. And again, I was making the point that the burden of finding out whether or not your water is contaminated rests solely on you, as a person who lives in this region. There’s no responsibility of the company after they built this pipeline. There’s no responsibility of any of the shareholders. None of those people are going to care about the folks who are left after this project is completed. If it’s ever completed. And no one is going to be there to support those communities or to support the people living up in the hills who lose access to their drinking water. There’s only going to be us who are left. And we have to like, not only find out while it’s happening, but also be aware after it’s happening that we have to continue to support these communities.

Emily: Yeah, I remember back when the pipeline was first announced and there were a ton of community hearings that people were showing up to just in droves to be like “We do not want this. Let’s make this very clear from the beginning, we do not want this pipeline. We think it is a bad idea. We think we will be put in harm’s way because of it.” They were absolutely right about all of that. And I remember, one of the ones in the Montgomery county area, folks were talking about some some people in the Brush Mountain area who were on well water. And the question put to, I believe it was county officials was essentially like “If our wells are destroyed, how soon can we get connected to the county water system?” And these were people who were maybe a five minute drive outside of town limits. They were five minutes from their neighbors who were on County water. Because it is a really difficult area to traverse and to build in safely. And because these areas don’t have a lot of disposable income for that kind of infrastructure investment. They were like “Three years. If it becomes a top priority for us from the minute that we decide “Yes, we’re gonna get you on to County Water. Three years.” So that’s obviously a long time to go without water. Yeah, and that’s already what’s happening as a result.

TFSR: I don’t know if you know the answer to this? But when people are resisting pipelines being built, and they go over schedule, and they go over budget by years and billions of dollars, if they’re just figuring that that’s like a normal part of the loss of the possible profits that they’re gonna be making, or if they’re contractually obliged to continue building it? Because projects do stop because of resistance. For instance, the ACP [Atlantic Coast Pipeline], right? As far as I know it went just so far over budget, and there was so much resistance at so many points that they just scrapped it. Which is an amazing story of success. But is there government subsidization? Like with the federal government stepping in and saying “We need energy independence, and so we’re going to fund projects like the MVP that’s keeping it afloat.” Or the hedge funds just so awash in money that this is an acceptable loss for them?

Emily: It’s a tough question. I studied economics, actually, in college and I still don’t understand how all of this really works. But I do remember talking to someone who was an expert in this. And essentially, because of the way that a lot of these companies are structured, they break the individual corporate entities down into being ‘midstream’, or ‘extraction’, or ‘processing’. They break it down into those separate categories. But they’re often owned by the same parent companies, or they have the same investors backing them. It’s this interesting sort of shell game where you really can’t follow the money very well. And of course, they also do really shady things like just straight up not pay some of their contracts and not pay some of their workers. That’ll happen to along the way.

But what I remember from that conversation with her and we were heading into a meeting with the governor or something, and she was explaining to me essentially, that you don’t actually have to have any gas flow through a pipeline for midstream partners and shareholders to make money off of that pipeline. It is such a bizarrely built industry and such an absolutely shady thing through and through. I do not understand where the money comes from most of the time and it seems to be a real confidence game where people invest in this. Then because people are investing other people see as a good investment and invest. It’s got the smell of a Ponzi scheme but I can’t get any more specific than that. But she really was like “No gas has to flow through pipeline for the people building it to make money off of it.” And that took my breath away. I still think about that conversation all the time. I wish I could find her and have her really spend a couple hours explaining it to me. But the industry is so craftily constructed. This has always been true of these industries. I mean, Enron was doing a lot of pipeline work and we know just how ethical their business practices were. It has always been this sort of like mystery fog that surrounds pipelines and fossil fuel industries. So that’s the best answer that I can probably give you. I don’t know if Toby can say a little more.

Toby: I mean, you’re the one that studied economics, apparently.

Emily: I try not to tell people that, honestly, most of the time.

Toby: I mean, it’s coming in handy right now. So I appreciate it.

TFSR: At least you’re on our side. So yeah.

Toby: I think we we don’t necessarily have a lot of economists who are giving us a lot of advice on how this system works, apparently. I feel like, I know that MVP is… if you listen to their shareholder meetings which are public, interestingly enough, you can tell that shareholders are not exactly happy with them. Which like, why would you be happy if you invested in a company that’s $3 billion over budget. They’ve definitely lost shareholders, but they apparently have not lost enough shareholders to say that it’s not worth it financially for them to complete this project. Even though we’ve also seen all of the economic trends that have been happening. Natural gas is not actually that good of a financial incentive. It’s not actually worth that much on the markets right now. And they’re trying to frame this pipeline as critical infrastructure. But in the end, it’s not going to be critical infrastructure, economic wise. It’s not going to be worth money. Dominion saw that. And that’s why they were like “We’re not going to do the ACP.” But the folks behind MVP have not yet made that decision.

Emily: Yeah, they haven’t wised up.

We have enough infrastructure actually to meet and exceed all of the natural gas demand in this area. So we do not need this pipeline for local gas demand. And we know that that’s true, because it won’t be going to locals. They they say that it’s going to be heating homes in the area, but it’s not. I mean, they signed contracts that have literally the bare legal minimum going into local consumption. It is entirely for export, entirely for that profit.

Toby: Yeah. And I think this is a trend. It’s not just this region where pipelines aren’t a financially good idea. Part of what happened with the Jordan Coe fight out in Oregon is that FERC [Federal Environmental Regulatory Commission] declined they’re eminent domain, because they’re like “There’s no financial incentive to grant the Jordan CoVe eminent domain. Natural gas is not enough of a financial incentive for us to deal with eminent domain of all of these landowner’s properties.” So like, like this trend of like it not being a good financial move is happening. But also at the same time it doesn’t benefit the company’s. The companies are like “No, we have to keep making money.” And, as Emily said, they don’t need to actually put natural gas in this pipeline to make money. And they’re going to continue being hell bent on this process, even though it’s at the expense of us living on this earth. And other creatures living on this earth.

TFSR: It’s obvious that they’re fleecing the shareholders. And that’s why they’re losing some of them, but some of them are just too dumb to realize. But it also just kind of smells to me, like the infrastructure plans that were over the last 20 years of war in Afghanistan. Where you just had like large infrastructure or private security companies or whatever taking public funds and building bridges to nowhere, as they say. Or just walking away with money. I don’t know if those are the same companies or if it’s public money going into it, but it just seems just ERRRRRRR.

Toby: Yeah, it does seem like that. It does feel like that, It is really hard to be like “Oh, this pipeline makes sense when you go around these mountains.” And you look at like their construction methods and the absurd amount of dangerous stuff they have to do to build this pipeline. In no way shape or form does this pipeline make sense. You just being here and hiking around… you’re like “Oh, this makes even less sense than I thought it would from an outside perspective, because of the terrain and where it’s going through.” You’re just like “How did any engineer think this project made sense?” I don’t know. As Emily said before, already, one worker has died. There have been multiple equipment accidents, where excavators have flipped over, other super dangerous stuff has happened on this pipeline route. So, you’re just like “Oh, it has to be something going on where people are ‘yeah, we’re gonna keep just drowning this projects with more money and even though it doesn’t make any sense.'”

TFSR: West Virginia is one of the states in the US that has a very long history of official acquiescence to extractive industries with, among other things, the promise of employment opportunities. There was already discussed the argument that it’s going to be fulfilling local supply needs for natural gas, which has been blown out of the water. But is this providing any reasonable amount of jobs for people in local communities? And is that is that one of the selling points that they’re trying to make for it?

Toby: They definitely make that point. It’s definitely wrong. You drive around and you look at where all the Man Camps are, where all of their work yards are, where their workers park, and all of those trucks are from out of state. Most of the pipeline workers are from other states where there are other pipelines being built. They get brought in. They come and they stay in Man Camps. They come in and stay at all the hotels. They’re from mostly out of state. I think the one exception to that is that some of their security they hire is local. But none of the bosses of the security folks are local. They all get brought in too. There’s a story that by where the Yellow Finch trees sits used to be, there was a logging project that was just coincidentally right next to it. And the loggers got into disagreements with all of the MVP workers because MVP had not hired local loggers to do the tree clearing, or the tree felling. So, they’re not hiring locals, they’re bringing people in.

Emily: Yeah, and I remember back in the beginning, again. They would waltz into these meetings being like “1000’s of jobs. We are bringing 1000’s of jobs to this area!” And people would be like “Really? Really???” And they would be like “Oh, we ran the numbers again, and we’re bringing hundreds of jobs! hundreds of jobs to the area!” And people would be like “Really? Really???” and then did their own research and they were like, “What you’re talking about in your own documents is less than two dozen permanent jobs, like less than a dozen permanent, jobs.” from what I remember from one of those conversations. Considering the amount of farms that I know that have shuttered in the construction process that has already out numbered. That’s already out numbered.

Toby: Even the jobs they’re providing to locals, the security jobs, as Emily was saying, they’re not continuous jobs. In fact, a lot of the security workers were pretty happy when a lot of folks started doing blockades again this year after the tree sits were extracted. Because it meant they were gonna get laid off, but now they’re no longer gonna get what laid off. That’s the thing is that they lay off a lot of workers. And even the workers that they bring in, they have large parts of the year where they can’t work, or there are stopped work orders and so they lay everyone off. So they’re not even providing jobs that are that good to all the folks who are being brought in.

TFSR: And just to keep on that topic around the Man Camps. I know when we’ve spoken to folks involved in resistance against pipelines, whether it be in so-called Canada or in the US. This can have different impacts in different places. Obviously, in in the parts of Canada where a lot of those pipelines are being built there’s large concentrations of indigenous folks living on their land, and being under threat of displacement or poisoning from this. And the Man Camps have a racialized element to them as a colonial force of displacement, as well as assault and murder against Indigenous women in particular.

But, I wonder if there’s some commonalities of experience around the Man Camps, as they’re called, along the MVP? I would imagine, and I’ve heard this sort of thing before that there’s at least higher like incidences of people transiting COVID because people are traveling back and forth over such wide distances and maybe don’t give a fuck about infecting locals at the hotel they’re staying at or the restaurant they’re eating at. But are there higher concentrations of assault around those spaces, or other concerns outside of the job site?

Emily: I mean, I’ll speak for myself here. I don’t really have a way of knowing and I’ve thought about this, and I don’t really know how to find out. A lot of those things probably wouldn’t go reported. We know for a fact that a lot of the man camps up north at Line 3 have recently been caught in sex trafficking, have recently been revealed as being sex trafficking rings. And again, They use Precision Pipeline. We use Precision Pipeline. There’s no way that it’s not happening, I guess, is what I’m saying. But I can’t necessarily speak to specifics of sexual violence around here. I will say that you’re absolutely right about the COVID transmission. I mean, they don’t wear masks. But also the cops don’t wear masks. Every every part of the construction process is putting… You know, the security workers don’t masks. A lot of the people who are out there are able to observe the people in their backyards doing the work every day. A lot of people that go out and do that observing are often older are often retired, because that’s who can show up when the people are working in their backyards. And so it’s a lot of older folks who are in close contact with these people who have no regard for their safety. None whatsoever. So yeah, you’re absolutely right about that.

TFSR: I guess getting back to the scripted questions. Thanks for going off so much with me. Can y’all talk a little bit about some of the history of resistance to the MVP? And what those old folks whose backyards are being despoiled by this… Who are some of the folks or communities that are resisting the pipeline?

Toby: Emily, would you like to start? You mentioned earlier that you have been doing this for seven years?

Emily: Oh, gosh, yeah. I mean, from the beginning it’s always been a really cross-demographic group I suppose. It’s actually, to me, been really beautiful being part of this community of resistance. Because I don’t think I’ve been in a lot of other spaces that are so multi-generational, across many different faith backgrounds, and geographically widespread. People really come together to show up for each other in this resistance. So that that’s been true since the beginning. I guess, when we talk about the people who’ve put their bodies in the path of the pipeline, it’s a lot of young people, it’s a lot of old people. It’s students. It’s grandparents. It’s people from far away that know that this pipeline is going to impact their futures and their loved ones futures. It’s people close by who have already lost their water or who also recognize that it’s such an incredibly urgent and far reaching crisis, that everyone is touched by it. And I think because of that, everyone really turns out for it. Yeah, that’d be my short answer. Toby?

Toby: Yeah. I think that what we see is there’s been years of resistance, since this project has been proposed, people like fought it through the regulatory process for years. It’s been opposed since the beginning. And while the regulatory fight has continued, there’s also been for over three years, a lot of direct action that has been used to resist the pipeline, and to stop construction that began in 2018, with the sits on Peters Mountain, in the Jefferson National Forests, where we had folks on top of the mountain in tree sits right next to where the pipeline would be bored underneath the top of Peters Mountain, which is where the Appalachian trail goes. And that’s the border between West Virginia and Virginia. One of the most amazing places I’ve ever been. I love that mountain. A lot of people here love that mountain. And it’s also an incredibly essential place for this region. It is a giant aquifer. It’s a place where there’s lots of different animals and species of trees, and all types of living things that are living there.

And then also, in the same National Forest a little bit later, there was the monopod that blocked construction for 57 days. That blocked one of their access roads that they use to get to their construction sites on Peter’s. So, I think there’s been not just an effort to fight them in court and to oppose them with regulatory process. But there’s been three and a half years of dedicated people putting their bodies on the line and risking their freedom to stop this project. We can keep talking about… We’re trying not to do the “And then this person did this!” I think the things that we were trying to think about this question and trying to be like “what are some of the major moments.” A lot of the major moments are where there has been a combination of local support and community support for these actions and for this type of resistance. As well as people coming to this region from all over to fight this pipeline. There’s been such a building of community that just transcends location and identity. It’s been like really incredible to see. Obviously, the best example, which is the Yellow Finch tree sit. They lasted for 932 days. And most of that was with the support camp. You met so many different types of people from all over who came to support the tree sits that way. And, obviously, that was just a space that a lot of people considered their home. But also was just a space to just build lots of resistance and capacity to fight this pipeline.

Emily: Yeah, being in that space was really special. Because you would see all these people coming from all over. You would build these amazing friendships. And obviously because people were coming from far away, there’d be a lot of coming and going, and a lot of coming back too. But then there were also the local people who I have memories of eating my friends banana bread in like week two, around the sits or something, and then memories of eating that same friends banana bread again, just a couple months before the support camp got evicted. That continuous local support that literally kept people fed and kept people safe and supported throughout is what has carried us through. There were tree sits that went up in Rocky Mount, they went by Little Teel Crossing. They were the Bent Mountain sits that lasted for five weeks. The monopod held for 57 days which was really incredible. That was the monopod on Peters Mountain.

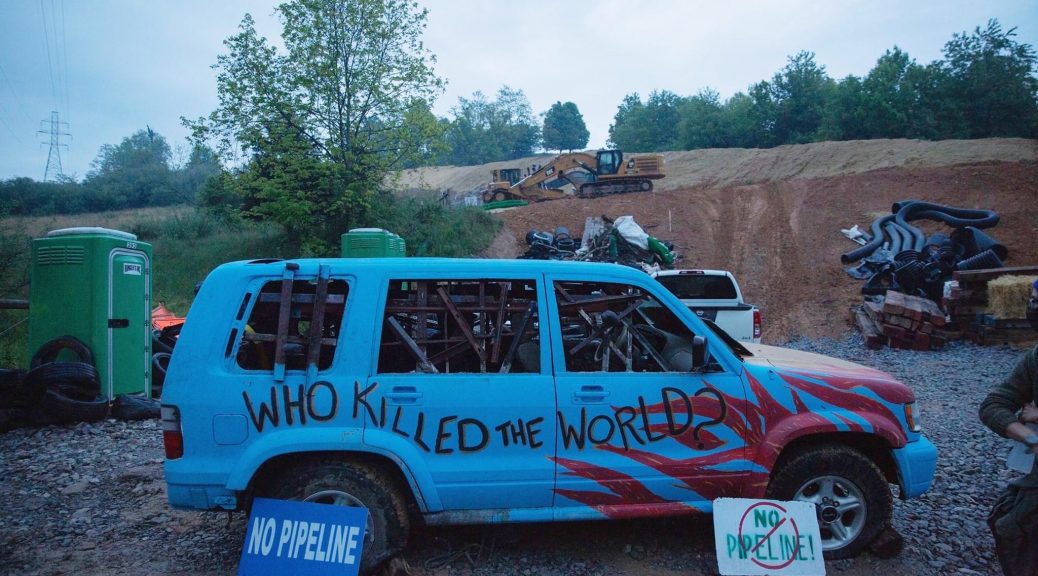

All of that together, all of those tree sits and large actions, and our recent mass action were 100 people walked on to a site and 10 people locked down to equipment, plus all those smaller actions that still had huge impact, where people lock themselves to excavators or just put their bodies on the line. Locked themselves into cars on the on the path of the pipeline. In total, there have been 74 arrests in direct actions against the pipeline across 40 actions, and summing up to 1039 days stopped over the years of resistance.

Toby: To be fair, that 1039 number is in large part due to the Yellow Finch tree sits, which lasted for 932 days. The distribution across that… the average is a lot different of blockade length. Some of the actions that have been done like the monopods and the tree sits and all of the different aerial actions have been some of the longest lasting active blockades. Not necessarily the longest, but has been some of the longest lasting blockades in the history of this country, or this land. And yeah, that combination of these long term blockades and also smaller, shorter-term actions, where people go and put themselves in the direct path, or locked to equipment or somehow interfere with construction is mostly because of folks who are willing to risk arrests and their freedoms. Also a lot of people from across the country seeing this as a fight that is really essential and connects us all. It’s the same with any fight that is against petrochemical infrastructure or extraction.

TFSR: So a lot of that resistance that you’ve been describing is on the ground. It’s people directly observing or directly standing in the path. And that’s great when people can do that. That’s part of the skill set that they can bring to resistance. I’ve sort of gotten a big appreciation over the years of talking to folks that are involved in the sort of work that you all are doing for the combination of the on the ground stuff, and also tying up the legal side of things. I’m wondering, are there any ongoing legal challenges around eminent domain or around FERC filings or anything like that, and any groups that are participating in resisting on that landscape?

Toby: Totally, there are. It’s also important to say that MVP right now is kind of tied up with their own permitting process. Right now the West Virginia DEQ [Department of Environmental Quality] just submitted a draft approval for their water quality permits. They also need all of their water quality permits that they would get through the West Virginia DEP [Department of Environmental Protection]. So those are for all their water crossings that they have not gotten variances for and done. I think they still need to do about 500 of their water crossings out of about 1000+. Some of those water crossings are major water crossings. The Elk River, the Gauley River, the Greenbrier River all in West Virginia or the Roanoke River in Virginia. They also have to cross under some major highway. And a lot of that will be done through boring which they also don’t have their approval to bore. That could get conditionally approved pending the approval of their Army Corps water crossing permits and their DEQ & DEP water quality permits.

Right now they were granted a new right of way permit to go through the Jefferson National Forest. But they can’t work there until they get the rest of their water permits. So they’re part of the legal system is that they didn’t wait to start construction until they had gotten all their permits. So they are trying to get their permits as they go. Which a lot of people say is that they’ve kind of like shot themselves in the foot. They’ve definitely limited their success by not doing what companies normally do, which is get all their permits before and then start. So that’s why they’re involved in a legal mess of their own making with all their permitting. Yeah, there’s also a lot of nonprofits in the area. Appalachian voices, the Sierra Club, and Wild Virginia, they are also in court challenging a lot of decisions made by regulatory bodies with regards to MVP. Do you want to talk more about that, Emily?

Emily: Sure. Yeah, again, from the beginning, everyone was all the local experts. Scientists were really clear that building this pipeline was going to further endanger already endangered species. A really good example of that is like the Kenny Darter, which is a really beautiful and colorful fish. The Log Perch… a lot of these species can only be found in Appalachia. And Appalachia is one of the most biodiverse places in the world. It’s really, really special in that way. There’s like a lot of limitations on when they can build, because there are endangered bats and birds that need to have their habitats protected. Which, to me is insane, that they should be able to build at any time of the year at all, if we know that those are their habitats.

But yeah, that decision made by Fish and Wildlife, that decision that MVP wouldn’t impact those species has been challenged in court, and it’s actually gone really far. And I believe they’re going to be hearing some oral arguments for that in the next few months, which is exciting. But I mean, that case was filed so early on. And I think something really important to note is that that case wouldn’t have made it this far, the pipeline would have been built if it wasn’t for on the ground resistance. Also on the ground resistance would have been a lot harder if they’d been able to build across all parts of the pipeline at once. So things like the endangered species case, things like the Jefferson National Forest case, challenging the Forest Service decision to let MVP cross the Jefferson National Forest, Those oral arguments are also coming up.

Those cases have made it so that their construction is slowed down. The direct actions have made it so that their construction is slowed down and those two different arms of of the resistance against the pipeline really support each other. They’re very deeply intertwined. Which I think is something that people don’t often think about. A lot of the times when people lock down in the path of the pipeline, you see this in resistance all over the place, people will be like “Oh, well, you know, why don’t you go through the proper legal channels?” And it’s like “Not only did we from the beginning, but we still are!” It’s really necessary to use these outside of the legal system paths in order to actually make it through the legal system because it is so rigged in industry’s favor.

The last one South Gate, the South Gate Extension, so that was a permit that they were looking for to be able to like build really the entire South Gate extension and the North Carolina DEQ denied their water quality permits. They came back saying “Oh, you can’t deny it for this reason.” They denied it again. They denied it a third time. Toby’s absolutely right. This process has been so messy and it is because of their incompetence as well as the fact that this project just like shouldn’t be built. There’s no standard in which this pipeline should be built. And then on top of that, there’s also still a lot of people fighting the eminent domain claims, where they live and some of those eminent domain claims have actually been pushed to 2022. And yet, MVP is constructing in their backyards right now. Which I think is just wild that they do not have the regulatory or legal standing to be doing so much of what they do every day.

Toby: Yeah, I think that Emily was talking about eminent domain a couple of weeks ago, and that mountain MVP was starting to work and that’s a place where there’s a lot of resistance to the eminent domain of the pipeline going through people’s land. And people came out every day through the night to be close enough to work where they [pipeline workers] couldn’t work for days, while there was stuff happening in the courts trying to get an injunction to stop MVP. Eventually, I don’t think that the courts granted that injunction, but it was a time where people like got together. And as simple as “Hey, we’re gonna be here, as a group of people, as a community and just watch what they’re doing, but also be close enough so that MVP can’t do the work they’re trying to do.”

Emily: That community, actually, some of the folks were out there every day, every night trying to prevent blasting from happening in their backyards. And eventually MVP and security got together with the homeowner there and gave this essentially verbal agreement that they would not blast until the case had been heard in court. The case was scheduled for later that week, and then in the middle of the night, without doing any of the safety precautions, which they’re legally required to do, they blasted anyways. So yeah, not only is the system rigged in favor of them legally in the courts in the regulatory systems, but they disregarded anyways. I don’t know if I’m allowed to say this, you can cut this out later, but they shit on it anyway.

TFSR: Yeah, Go ahead and say that.

Toby: Yeah, I like the point that Emily made earlier that people who are taking MVP to court or who are challenging decisions that the regulatory bodies are making in court, all of that builds time and space and delays in the construction that allows more resistance to happen. So whether that’s more resistance, like monitoring, or more legal challenges, or the direct action element, this fight would have looked a lot different for the past three and a half years if they were allowed to work on every segment of their pipeline at once. And it would have meant a much different image of what resistance looks like against the MVP.

Emily: Very succinctly put.

Toby: It also has meant that folks have had this challenge of sustaining resistance. I think there’s an extra challenge in that too. It not only creates space for more resistance to happen, but it also creates a challenge to sustain the energy and the resistance. And a lot of that energy comes from local support for the fight against MVP. These people are not leaving, they’re not moving, they are still fighting this in their communities in this region. And so a lot of the ability to sustain direct action over three and a half years and a legal fight over seven years, is the dedication and energy of the folks who live here. And it’s been pretty cool to see that be sustained. I feel like a lot of times with direct action, it’s very urgent, it’s very fast. How do you make sure that we still have support, and we still have there is still people who are like willing to put their bodies on the line when it has lasted over multiple years.

TFSR: It’s really inspiring. There’s been this group that’s at least has a social media presence, called “Appalachians Against Pipelines” that’s been doing a very good job for a very long time of bringing up news about the resistance that’s been going on against the MVP. And just making space for criticisms, and for news of resistance, and for ways for people to get involved and for fundraisers, and all sorts of different stuff. And it’s come up I guess, in federal court, where Facebook is being pressured by MVP, as I understand by the Mountain Valley Pipeline economic project, and construction project, to try to get information about the people that are behind AAP’s social media presence, or whatever other presence. I don’t know if that’s for the purpose of a SLAP suit or what. But can you all talk a little bit about this circumstance where social media is a very useful tool for sharing information and for rallying people but it’s also potentially being weaponized against folks who are speaking out against the Mountain Valley Pipeline project?

Toby: Yeah. Appalachians Against Pipelines just describes grassroots resistance to Mountain Valley Pipeline. As like a Facebook presence or social media presence it exists to help the fight gain visibility and educate people. It published news about the regulatory process in the legal fights, as well as news about different direct actions that people take. And it’s also to act in solidarity with other resistance struggles. That is the purpose of that Facebook page. And as of now, no admin for that page has been contacted by Facebook about the subpoena. So, there’s been no communication with Facebook as of right now that I’m aware of.

I think it’s pretty important to note that this is not the first time that MVP has used this type of intimidation to try and stop resistance. It’s a harassment tactic right now that they’re doing. And it’s just trying to seek out personal information, not just as like “Oh, we want to know who is behind this Facebook page.” But it’s also a scare tactic to discourage people from joining resistance but it’s also a scare tactic to try and get people to stop. Because it is terrifying to have a company know your personal information and your name and your address and whatever else the subpoena is asking for. It is terrifying to know that with the reality of SLAP suits and injunctions, and also police investigations and other law enforcement investigations. It is scary to have that like be a tactic that is being used against people fighting MVP.

TFSR: Or private security companies like Tigerswan that were conducting surveillance and counter intelligence work up at the Dakota Access Pipeline protests.

Toby: Yeah, it’s harassment, and it’s intimidation. And I think folks who are resisting that Mountain Valley Pipeline, this is not the first time that this scare tactic has been used. This is not the first time that MVP has harassed people and intimidate people. And so I think that as before people are going to continue to resist this pipeline and refuse to be intimidated by Mountain Valley Pipeline and their subpoena.

Emily: Yeah, and I would add that, you know, this is just kind of my personal perspective, but it seems like a very desperate and cowardly tactic. I think all intimidation harassment tactics are. It has this very cowardly and disingenuous ring to it. I’ve seen people very courageously… the risk is real, the threat is real. And also, it’s disingenuous because people have been standing up vocally with their faces and their names out in public ready to take on those consequences from the start. And so to act now, like “Oh, there’s this shady group behind it all” is absolutely trying to disempower people in this area, and everywhere who have been vocally and boldly from the beginning been saying that this is wrong and been saying it in the face of a behemoth of a corporate behemoth and in the face of the state.

Toby: I think like in general, you see, other fights have similar social media presences. And we’re now the age where social media is used as a way of not only getting the word out about different actions and different fights and informing people but it’s also an incredible tool to get inspired by other fights across the world. It is how people like learn about different people resisting and different struggles. It just emboldens everyone. It emboldens people around here to see other campaigns or other fights going on and what those people up at Line 3 are doing putting their bodies in line. Like how they’re doing that. Or seeing the fights going on at Fairy Creek or against Trans Mountain or Coastal Gas. Learning about what other folks are doing is incredibly important to sustaining the fight here. So that’s kind of the benefit I see a social media presences of these types of resistances of course, also more it does open people up to more risk. It does. This is not the first time this has happened against a pipeline fight.

TFSR: It’s so inspiring to me the the correlation between the hyper-localized, like “this is what this landscape is, these are the animals that are impacted, these are the people who are being impacted, this is the landscape.” And then seeing the map dotted with projects that are similar where local people or people locally are resisting or coming from other places to go resist And looking at the fact that there’s this web of solidarity between the groups. The scope of damage and threat is not just local, but it is local, and that can’t be diminished. But it’s also global because of fucking climate change. It ties these struggles together and co-inspires them. My mind just reels at the thought. It’s so inspiring.

So, since President Biden has come into office have y’all seen any changes in the pushing through this pipeline, any differences from the way that the administration’s of Trump or Obama interacted with the project?

Emily: So there was a FERC nominee put up by Biden. A lot of people say that this nominee is also a fossil fuel crony, which, of course, is like nothing new for the Federal Energy Regulatory Committee. I’m sure there’s a lot of specific policy details that people could debate back and forth. But the reality is just “NO!” when you’re putting your body in the path of a pipeline, and the cops come to arrest you, it does not matter who the President is. The history of this country is a history of extraction, it is a history of exploitation. That has been consistent from day one. And this mega project, this massive project, this historic project really does just slot into a long line of similar devastating, high risk, destructive projects. That history, you know, it’s not like it has four years on four years off, it is a consistent history throughout.

Toby: Yeah, and I think Biden has paid a lot of lip service to wanting to fight climate change. But as we’ve seen with pretty much every single politician ever, it’s just lip service. No on is willing to take the actions that are needed to stop the impending climate crisis. No one is willing to take the strong enough action to actually limit emissions. It’s one thing to say what you’re trying to get elected, “Oh, I want to fight climate change.” But when you are actually elected, and you do nothing to stop the projects that are going to drastically impact our world by releasing so many emissions and are so far out of the realm of what you should be doing to actually stop climate change. And you’re like, “Okay, well, great. Another politician saying the thing doing nothing. No shocker. No surprise.”

TFSR: So, for folks in the southeast of Turtle Island, like in this region, how can they get involved? Or how can we get involved with a the anti MVP struggle in our own backyard? Who do you want to show up? And what sort of stuff can folks do remotely to support it also in case they can’t show up on the ground?

Emily: So yeah, there’s a lot of different ways to plug in. I mean, we so appreciate all the people everywhere who have donated. Who have started their own fundraising methods. Who have done solidarity actions at banks, demanding divestment or cutting ties. But also, if you want to come all the way to the mountains and join us, then come! You know, we want people who are dedicated to stopping the pipeline. We would love to have you. But also if you’re not near us and there’s a fight near you join that. Contribute to that. All land and water defense is really connected. And if there’s any abolition work, or any other kind of liberation work where you are, do that. Plug into that and that would make us really, really happy.

Toby: Yeah, as you said earlier, we like thrive off of that web of solidarity. We thrive off of seeing other folks in their communities fighting for liberation, fighting for native sovereignty for land, for landback, against extraction, against petrochemical infrastructure. We thrive off of that. And so if you can’t come out to the mountains join whatever fight is closest to you.

TFSR: 1492 Land Back Lane is an ongoing struggle in so-called Canada that is really inspiring. Line 3 has been in the media a lot as a place where tons of people, both indigenous folks and co-conspirators have shown up to put their bodies on the line to try to stop that construction. And I wonder, can you say anything about that struggle and if there are other… You mentioned the struggle On Fairy Creek for instance. Can you talk about any other struggles that are that you’re taking inspiration from that are land and water defense or land back struggles that you want to shout out or inform people about.

Toby: I personally, I’m pretty excited to see all the stuff that’s happening in Atlanta against Cop City. And I am excited to see the beginnings of the organizing that’s happening there. And I’m excited about that. Inspired by that.

TFSR: Can you describe what that is?

Toby: Yeah. So in Atlanta… I’m not definitely not the expert on this. Atlanta has a lot of parks, lots of forest in and around it. And there is like a massive project that is being proposed to deforest some of the land around it where the product of that would be half of that land would go towards the movie industry and then half of that would go towards building a cop training facility that I think people are calling Cop City. And that definitely is a struggle that is at the intersection of abolition and fighting resource extraction and deforestation. But also intersects a lot with the struggles against gentrification that are happening in Atlanta, and pushing people of color, Black communities out of Atlanta. It just seemed like the intersection of all of these different fights coming together in one is pretty inspiring to me. And that being so close to us as well is nice to see that blooming and coming up.

Emily: Yeah, first of all, I fully agree with everything that you just said Toby. And to jump off of what you were saying earlier about Line 3. I think staying up to date on that fight is huge, It’s really coming to the point where Enbridge is absolutely racing to finish. I mean, they are being reckless and just railroading over. But the resistance is still ongoing, which is incredible considering the real intense ramps up that law enforcement have been using, the violence that they’ve been using against water protectors there has been oftentimes hard to look at. But we can’t look away right now. And with the hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of people who are now fighting their arrests and charges in court, ongoing court support for that fight is gonna increasingly become something that I think people from far away, can plug into. And so that’s something that I’m trying to learn a lot more about right now. And I’d encourage people to keep their eyes out for that.

TFSR: How can people keep up on the struggle against the MVP? And what are some good sites or sources or fundraising pages or whatever that they should check out?

Toby: To revisit this, check out Appalachians Against Pipelines? That’s a very good source for information and updates and also the donation link to support resistance. We also have a podcast coming out.

TFSR: Hell yeah.

Toby: We also have a podcast. Emily do you want to talk more about the podcast?

Emily: The first episode will be out soon on In This Climate which is a really great podcast. And then the following episodes that we’re hoping to put into production soon will definitely be shared on the Appalachians Against Pipelines social media, which is Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. So you can find them there.

Toby: That podcast is gonna focus a lot on people’s stories, and listening to the people who’ve been involved in this fight. So it’s a lot about people’s personal experiences and reasons why they have joined in.

TFSR: That’s awesome. Yeah. I get a surprise too! Cool. When is that first episode gonna be out?

Emily: Good question. We don’t have a date yet.

TFSR: If it was by the end of the week or something like that, then I would totally drop a link in the show notes.

Emily: It will certainly not be by the end of the week. But hopefully within the next three weeks, maybe?

Toby: That’ll definitely go out on social media. So people should follow Appalachians Against Pipelines to get notified about when there is a podcast coming out.

TFSR: Absolutely. Toby and Emily, thank you so much for this conversation. Thanks for all the work that y’all are doing. And yeah, solidarity.

Toby: Thank you so much for having us.

Emily: It’s been so great talking with you.