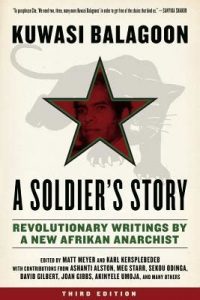

In this interview, Bursts and Matt discuss Balagoon’s life and writings and why this book is especially relevant right now. They’ll talk about his abiding love for his comrades, a things which seems to have driven much of his politics, and his queerness, an aspect of his life which seemed very important and also complex. Stay tuned to the end of the conversation for questions submitted to The Final Straw by imprisoned anarchist Michael Kimble, who has been a guest on this show and is an admirer of Kuwasi. To see more of Michael’s work and to write to him, you can visit anarchylive.noblogs.org

We got way more responses than we ever thought we would, and are working through to answer them in as complete and responsible a way as possible. If your interest is piqued and you wanna hear this episode, it’s up on our website along with all our other archived material.

. … . ..

Music at the beginning of the show was an instrumental version of Hip Hop by Dead Prez off of Let’s Get Free.

. … . ..

Transcription

TFSR: So your author page on the PM Press website lists you as War Resistors International Africa Support Network coordinator and a bunch of other titles that are part of these committees. And one of the commonalities among the organizations that you are listed as working with is “peace” or like an opposition to militancy. So I’m wondering if you could introduce yourself and also tell listeners a little bit about how you found yourself co-editing a book about an urban guerilla in the US?

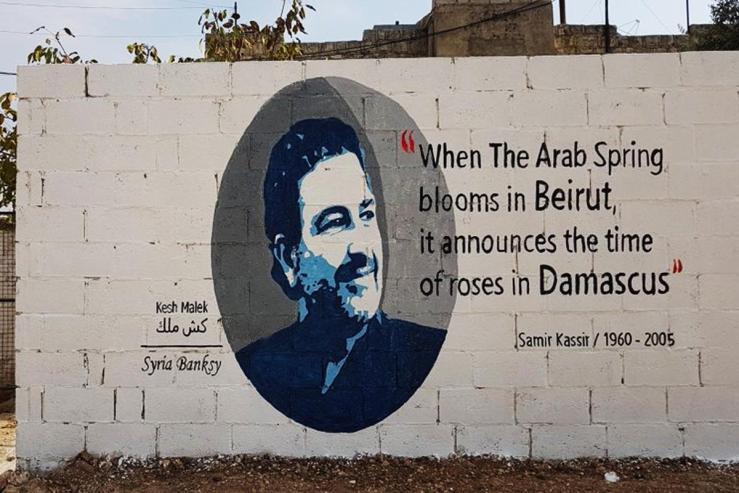

Matt Meyer: Ok First we have to speak about “in opposition to militancy”, because I’ve never been opposed to militancy. I am in favor of militancy. And I want to say something about a leader, who is actually now… in certain parts of the US left & progressive circles, getting some more attention, I think more and more is necessary. He was an African liberation movement leader. He was a military commander, his name is Amílcar Cabral. And Amílcar Cabral was the essential center of the movement for independence and freedom of Guinea-Bissau. He was one of the great Pan-Africanist of the 60s and 70s. And he was, again, a military commander. He is probably most famous for giving the speech that contains within it the phrase, “claim no easy victories.” The idea that we can go about using a bunch of pumped up rhetoric and say “we had 10,000 people” when we only had 100 people to rally. So, claim no easy victories. He was telling it to us and he was also telling it to his troops to his armed combatants. He was saying “when we go into a town, when we go into a community, when we go into a village, whether we do it to liberate them, whether we’re doing it to defend territory, we’re looking to liberate the country. We can’t take a thing from them. We can’t take a stitch. Not a loaf of bread, we have to give back more than we take. That’s what our job is as radicals, as revolutionaries.” and Amílcar Cabral, in that same famous speech, where he said “tell no lies, claim no easy victories” also said something that’s not as well known that I go around the country and go around the world quoting, he said to these armed combatants, these troops liberating their country from Portuguese colonialism. He said, “we have to learn to be militants, not militarists.” Militants. Not militarists. So there’s a big difference between being anti-military, anti-military industrial complex, and being anti-militant. I’ve been a pro-militant all my life, we have to increase the confrontation, we have to increase we have to intensify the struggles against Empire, against patriarchy, against white supremacy. And what better way of doing it than by spotlighting the life the work the legacy of Kuwasi Balagoon: Black Liberation Army, Black Panther Party, Panther 21.

TFSR: Cool. Thanks for letting me jump into that the really awkward way. I meant to say militarism, but you took it, right there! Can you introduce yourself now that we’ve heard your hot take response?

Matt Meyer: Bursts, thank you. And it’s really a pleasure to be here, and great to be in North Carolina at the studio. Yes. My name is Matt Meyer. Yes, there are a lot of organizations after my name. I know this is only an hour show. So we won’t talk about all of them. But, you know, I was in part a student of Pan Africanist. Kwame Ture. Stokely Carmichael. And he said “you know, if there’s anything you do from whatever perspective, if you’re looking to make social change, you have to organize, organize, organize!” Sorry, Will mentioned some of the organizations because the organizations are important. Yes, for the longest time, for many decades, I’ve been involved in the War Resistance Movement, I started out as a 17-18 year old, who was called upon to register for the draft. I was one of those public registration resistors. It’s useful to note that now, because even at this very moment… Selective Service has been challenged just recently by a federal court case a few months ago. That said, it’s actually unconstitutional to register only men. So now they’re trying to figure out whether they should do away with the entire process of registration, or, of course, what they would like to register women as well. But that’s a conversation going on. And of course, those of us who are in the anti-militarist movement, say that’s a no-brainer. This whole policy has become a failure. It’s both been a failure, from a point of view of creating a more just society. But it’s also even been a failure from their own standards of creating a policy that makes us more ready for whatever it is the US wants to get ready to do. So War Resistors League in the US, and War Resistors International. And the part of War Resistors International, that for the most part has been Africa support work, supporting groups like the War Resistance movement. In every part of the continent of Africa.

I went on academically. I started when I was 18, as I say, but I went on academically to become a student of contemporary African history. I’m still a student, but I also became a professor. Now I’m a retired professor. So building the Pan-African movement and supporting African movements on the ground today, that are using war resistance and anti-militarist methods to make social change. Revolutionary social change is a big piece of my work. There are two main other organizations that I work closely with and that define me, and that are worth mentioning. And then one local project I’ll just say quickly. I am currently the national co-chair of the Fellowship of Reconciliation USA. Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) is the US oldest interfaith peace organization.

I’m here in Asheville, doing some speaking here in North Carolina and Georgia doing a speaking tour, that FOR is co-sponsoring, along with PM Press, the publisher of Kuwasi Balagoon’s: A Soldier Story. And the FOR is not only the oldest group, but it’s a group that has been concerned for almost 100 years , actually, I’m sorry, now it’s a little bit over 100 years. The War Resistor’s League (WRL), and FOR were founded a few years away from each other. So WRL has almost 100 and FOR is just a little over 100. I am younger than that, by a long-shot. But I am one of the elders in both of those organizations. In addition to being slightly over 100 years old and concerned with peace issues, concerned with issues of reconciliation, it has also been at the forefront of movements for racial and economic justice. The very first Freedom Rides actually were 1947 (not the 50s and 60s versions that we are more familiar with). In what was called the journey of reconciliation. And we work closely by addressing who was on staff of both FOR and WRL at different times. So right now the FOR is looking at a new way of understanding racial justice, economic justice, and peace. And that new way is by understanding both the institutional and governmental, but also the individual responsibilities for Reparations. What does it mean, to build a movement deeply for Reparations within a society like the US Empire?, that may be dying. That may be really in some ways in death throes as an empire, but still has tremendous repairs to make even as more harm is being done to people of African, of Latinx, of indigenous descent. And so that’s the FOR. And that’s one piece of my work. And then the last organization, is I academically, as I said, went into teaching African Studies. And it was in the context of an emerging discipline that’s been around about 50 years called “peace studies” or “Peace and Conflict Studies”. And so last December, I was elected the Secretary General of the International Peace Research Association. So actually Do most of my work around the world. But occasionally I get to tour around the US, and especially my base.

So I’m a New Yorker by by birth, and part of my heart is definitely here in North Carolina. But academically, I’m the senior research scholar at the resistance studies initiative at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. It’s not so much the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, it’s the fact that there’s a place in this empire, called the resistance studies initiative. There are not many departments, in fact, only one called the resistance studies initiative. And so I’m happy to be a senior research scholar in that particular program looking to bridge the gaps, from the gown to the town from the Academy, to organizing, grassroots organizing. And so we put out books like this, to understand that there’s a history that we need to recover that we need to uncover, as we’re rebuilding people’s movements.

TFSR: That’s awesome. A very complex answer. So for folks with an older edition of this book, just published, originally published by Kersplebedeb. Man, I might be pronouncing that…

Matt Meyer: Wrong? You are pronouncing it correct!

TFSR: I’ve practiced it first. What differences would they find in this third edition like it’s notably thicker? The prior edition solicited additional material from readers at the end, which I thought was really clever. But can you talk about what process y’all went through in building this version of Balagoon: A Soldier’s Story?

Matt Meyer: Yes, this is one basic answer. And it’s way, way shorter than my previous answer. What is different about this version? More. It’s more, you know, the Soldier Story… and this, this is true for many things that get published in this way. It was thrown together in order to have an in print space for some of Kuwasi’s work. And again, for those who don’t know, Kuwasi, and I’m sure you’ll do, or have done a little introduction, but, you know, this is a person who’s essentially a Black Panther, revolutionary, nationalist, anarchist. This is a person who is a freedom fighter, a soldier, who is also a pussycat, lover of the people… playing with kids on the floor. So you know, Kuwasi, in some ways, is symbolic of so many of the apparent contradictions, that are really part of our whole human-ness that we like to pull together. And so even back in the day, after he passed, but you know, long after, but still, his memory was in some people’s minds, lives, and thoughts. The idea of pulling together some of his pieces of writing, some of the things that he’d put out as pamphlets or as articles in his life.. that that was necessary. And then another edition came out. And when that second professional kind of book like edition, first came out, it satisfies that need.

I guess it was two or three years ago, my co-editor called Chris Kersplebedeb, one of the founders and mainstays of Kersplebedeb, noticed that that second edition was about to run out. That it was simply going to run out of print. He said… a few of us said, “what are we going to do? because we could just simply reprinted or we could do something else!” And that something else that we decided to do was: to really go deep and get every single shred of writing, every video, audio, everything that Kuwasi did that was available, and transcribe it and type it and put it into print. And also take some space for those who knew him, or for those who most directly followed in his wake, to write about their feelings about his life and his legacy. So for example, this book has an incredible historical biographical overview, by the Georgia scholar, Akinyele Umoja. He’s he’s a great New Afrikan leader, one of the founders of the Malcolm X grassroots movement, and Akinyele’s work… the incredible, absolutely significant book We Will Shoot Back is well known. But this special piece he wrote that really brings Kuwasi’s relevance to the 21st century, is reprinted was printed in an academic journal. It’s reprinted as the front article in this new edition. There were a number of Kuwasi’s friends and extended family who had scraps of his writing.

My partner in fact, visited him and knew him and had an engaged correspondence. And though we didn’t reprint all of those private letters, he would often attach poems. Sometimes finished, sometimes ones that hadn’t been seen before. And sometimes just on the spot, he was bursting with poetry. He spoke in poetry from what I heard! And reading some of the letters, the letters themselves are poetic. We extracted the things that were clearly not just personal, you know “how I’m doing How you doing?” but the poems, and printed almost all of those poems in this volume. There were special little projects that may not have been completed. We think this one was. There was a “how to how to stay healthy in prison” an exercise book that we’ve reprinted in here. And yes, we’ve already heard from some people inside and people outside saying “Oh my God! we need that exercise book now! we need this more than ever.” And, so we took as many… I will tell you, this is one of the problems about being the kind of editor I am. I’ve edited other books with PM Press, and this is very restrained. This is PM Press and Kersplebedeb co-published, but some of my PM Press’ are over 1000 pages long. I’m the kind of editor that doesn’t like saying NO, who wants more and more. And I will tell you, and I haven’t said this publicly before but I’ve heard about one poem that we cannot find. And we just decided we can wait 10 more years and maybe or maybe not find it. If whenever, I don’t know… if we find it, we’ll let everyone know. But basically, we think we’ve gotten almost everything that he put into writing, including a couple of pieces that clearly were pretty unfinished, and we decided to err on the side of publishing it all. And then lastly, we collected a group of two or three of his closest comrades. There are two people wonderful, extraordinary elders. Sekou Odinga, former political prisoner did 33 years in prison, and the great jazz saxophonist and also former Grand Jury Resistor Bilal Sunni-Ali. Sekou and Bilal both each claim to have been the ones that recruited Kuwasi into the New York Black Panther Party. They debate that out a little bit in these pages, and we’ll let them continue to do that. But many, many other, you know, a good dozen other people who again, either knew him well, knew him a bit, or grew up in his legacy. I’ll just name one other person that the multi-talented poet, actress and multimedia artist, Kai Lumumba Barrow, who was based for a long time here in North Carolina, and was part of the Southerners On New Ground (SONG) organization. Kai is one of those who has both part of the conversation between people who knew him and her own poetic legacy interpretation of Kuwasi in here. So that’s the final part, some pieces by people who said, this is why Kuwasi is absolutely a person to look at in 2019 and 2020, as relevant now as he ever was.

TFSR: Can you talk a little bit about Kuwasi’s life, like a thumbnail sketch of his background and development?

Matt Meyer: Well, I wasn’t one of those who knew him, I wasn’t, and I actually have a small section I want to read that mainly quotes from Sekou Odinga because I have gotten to know and work under the leadership of, and really be privileged to be part of the current life of Sekou Odinga, who knew him when they were both youth. So I’ll quote from Sekou. But I want to say something about our orientation, our vision towards Kuwasi. And that question of 21st century relevance in putting together this book. We are at a time now, as radicals, where we clearly need, I think, more clearly than ever before: militant, radical, revolutionary social change. Whether violent, nonviolent, armed, unarmed, social change, and radical social change is an urgent task for the empire that is dying, known as the US. And the fact of the matter is, despite that understanding many of our lives, and many of our movements are in silence. We have this little group here, that group there, this campaign here, that campaign there and never really an overarching building movement.

Now Kuwasi made his decisions. He was a member of the Black Panther Party. And before that, he was a housing rights activist in Harlem. He was a member of the New York Black Panther Party. He was a member of the case of the New York Panther 21, which was the New York militants. In some ways they were really pulled together by this wild and crazy FBI investigation, and then New York State indictment and campaign. And then after that, he went underground and was part of the Black Liberation Army. And even after the Black Liberation Army, had been targeted, and in some ways had had some of its militants captured and killed, Kuwasi continued doing clandestine work underground work until his capture in the early 1980s. And so Kuwasi, despite that little thumbnail sketch, was a person who did not, who could not live in silos. He could not segregate. He had his revolutionary nationalist analysis as did most of the Panthers, but he could not live his life segregated one piece here, one piece there, one piece over there. So whether it was about sexuality, whether it was about black and white, whether it was about inter-generation, whether it was about violence/non violence… Kuwasi loved people. Kuwasi’s story is about being radical, being a militant, being a… how did you say before you know, a member of an armed you know, intensely urban guerrilla, he was all those things, but he was also extraordinarily non-sectarian and loving about the people. “At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love.” That’s a quote from Che Guevara. But lots of other revolutionary leaders of all stripes and nationalities, violent or non-violent, have that same reflection. Kuwasi, from everything (I’ve heard everything I’ve read everything) we understand, personified love of the people.

TFSR: Yeah, and that that comes across in a lot of the reflections, as you mentioned, from a lot of the people that knew him. A lot of the things that I’m more familiar with from the second edition. But there are really moving sections about how like, you would just find him in the prison yard surrounded by a bunch of people just breaking on laughter, or, like you said, sitting on the ground playing with kids just tumbling around like nothing.

Matt Meyer: And it’s interesting, you know, Sekou, again, another incredibly, you know, and rightfully, well respected elder of the Black Panther and black liberation movement. He said, you know, the questions of white and black, we weren’t as advanced. Kuwasi, somehow, it’s not just about being naive. It’s like, understand that there are some allies that you’re going to have that connection with, you know, the Panthers were never a cultural nationalist group, they never said, they always, always build alliances, even the splits within the Panthers… West, East, whatever. You know, the entire Black Panther Party for self defense built alliances with white groups, with the Latino, Puerto Rican, Chicano groups, with Asian groups, etc. Those alliances were part and parcel of their politics. Kuwasi lived it on a very deeply personal level. So some of these issues of black and white that organizations and individuals are still struggling with now. Kuwasi had in some ways transcended. But let me actually read a little bit. So we get to hear Sekou voice about Kuwasi.

“I probably met Kuwasi in the spring or early summer of 1968. And he was always a real energetic brother. You’re always going to hear him telling a story or joke, or enjoying one. He was always full of life, always ready to volunteer for any work that needed to be done: the more dangerous the work, the more ready he was. He was real, sincere, and dependable. That was what struck me early on. He was always ready to step up, even if you didn’t need him. He would volunteer; it wasn’t something where you ever had to go find him…. Kuwasi loved life. He clearly loved life and loved living life. He was always ready to live… He was a living dude, and most of us all really loved him.”

So that’s Sekou Odinga talking about Kuwasi and that’s in that roundtable of love and reflection we did. And I’m going to read one other little piece that we the editors wrote that summarizes that reflection in some ways it summarizes this edition and why this edition, how this edition came about to be what it is bringing pieces together into one whole. UNIQUE!

“Unique. The single word most often used to describe Kuwasi Balagoon, when discussing his life and legacy, with those closest to and most affected by him, is unique. That Kuwasi. His way of living and looking at life, set him apart in special and wondrous ways, even in the midst of amazing friends and colleagues, and even while living and working in extraordinary times. Kuwasi stood out distinction surrounding other labels and descriptions. New Afrikan. Revolutionary. Nationalist and Anarchist. Gay. Bisexual and or Queer. Poet. Militant. Housing Activist. Panther. They can be discussed and debated and reflected upon. But Kuwasi’s greatest quality was surely his lasting love for the people and his ability to transform that love into tangible acts of resistance.”

Bursts: you’ve addressed a couple of the questions already up in here I get my footing again. So you’ve noted you know the the timeliness of the addition coming up the older copies being gone and that inspiring y’all in part to to produce the new edition. Kuwasi has also kind of come up in, among other people that I’ve seen, for instance, the Revolutionary Abolitionist Movement (RAM) has a Kuwasi Balagoon Liberation School that they’ve been with their their program that they’ve been running for a couple of years now. Besides the need for being able to transcend, transcend these differences and create a movement of movements, besides like fulfilling that need, do you see any other reasons why Kuwasi’s writing would be coming to the fore, and from all these different places?

Matt Meyer: I mean, it’s interesting, I think, the idea of looking back to move forward, the idea of looking at past strengths and weaknesses, to build and rebuild. For some reason, when you were asking that question, I was thinking of my dear brother, Ashanti Alston, who is now in Rhode Island. He was in New York for a time and he always described himself as anarchist Panther. Now, Ashanti himself was a very, very young brother, who was part of the Black Liberation Army and who did some time. But when he came out, embracing Kuwasi’s ideas of revolutionary nationalism, and anarchism of being an anarchist Panther. It was something Ashanti both held on to, improved upon, but also built upon, built upon and helped grow in the movements of the 90s and the early 21st century. And so the very specific place where Ashanti did and does that most, isn’t a place called the National Jericho Movement. And the National Jericho Movement, as some may know, is a national / international campaign to free all remaining political prisoners and prisoners of war in the United States. And it’s a horror that one of Kuwasi’s own co-defendants Sundiata Acoli, a member of the Panther 21 you know, is also a co defendant of Sekou Odinga still languishes in prison after 40 years, more than 40. And after passing, you know, birthdays, people shouldn’t be in jail for the 17th and 18th birthdays. That’s ridiculous. So this man who actually was a NASA mathematician, who should have had movies about him, like “forgotten here”, you know, whatever, you know it. This is one of the great minds of our times who is in jail because he decided to use that mind and that body for the liberation of his people, by becoming a Black Panther and a militant. So the intensification of the campaigns to free all political prisoners, like Sundiata Acoli, like Mutulu Shakur, like Imam Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin, another great legacy leader from the 60s known before as H Rap Brown, who was a lead of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, student National Coordinating Committee, became a Muslim Imam Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin, in jail today.

So we talk about the 60s or the 60s & the 70s. And we talk about reconciliation. We talked about moving forward, and in fact, we have never moved forward. These brothers have been in jail Since the 70s, since the 80s. Again more decades, then mass murderers and rapists, you know, people who have committed horrific crimes against the people, these people who have fought for the people… remain in jail. So I say that both because I want listeners to, if they haven’t, look up the website, National Jericho Movement, look up what that organization is doing. And the list of all of the prisons, I only named a few, most of them from the Black Panther movement, and organization, but not just. And we have gotten some political prisoners free. I mentioned Sekou Odinga. But the fact of the matter is, they all must come out! Now it’s time to free them all. They are getting to an age where if we don’t do it soon, we will have lost the opportunity. And these are our elders and leaders who have many cases, the most profound and inspiring stories to tell us now, again, about those strengths and weaknesses of the past.

Bursts: I’d like to mention really quickly that this last week, we saw the release of Janine and Janet Africa of the MOVE organization, which is awesome. FREE THEM ALL.

Matt Meyer: Indeed, FREE THEM ALL.

Bursts: So this is an anarchist podcast, and I would like to know, and other people have asked: How, to your knowledge and as it came out in the book… how did Kuwasi’s political development come to anarchism? And how did he relate that to a revolutionary nationalism?

Matt Meyer: That’s that’s a very good question. And I think it’s, again, one of these questions of terminology. Like militarism and militancy. And the question came up: “To what degree did Kuwasi use the word anarchism?” And I think the answer to your question is best posed this way. Even in his day, and even among his comrades and his colleagues, Kuwasi was always a deep anti-authoritarianist. It wasn’t about ideology wasn’t about saying, “hey, let’s not read Marx, let’s read Bakunin.” It was about saying “we can’t create structures that chain ourselves, we can create hierarchies.” Now, that doesn’t mean that you’re not a disciplined, accountable member of an organization. And all great anarchist revolutionaries know it’s not about chaos, it’s about organization. It’s about liberating organizations. We’re accountable to one another, not to one great leader, who we decide is… you know, the king. It’s always a man. So you know, I say the king advisedly. But the fact of the matter is, that I think the best way in which he embodied it was in his life. He was a deep anti-authoritarian, always suspicious, always critical, always concerned about undue authority. That wasn’t about accountability to the collective, but was about one person or maybe a couple of people getting more power than they needed. More power than was healthy, for a well functioning collective. I think it’s worth saying it’s also an interesting piece of Kuwasi’s life and legacy.

In terms of this question of gay or queer. I think it’s pretty clear that he never self defined in those ways. And yet, it’s also clear that at some point in his life, he had a lover who was male or trans-femme. Again, that term wasn’t used at that time. So it’s hard to put words in people’s mouths that weren’t in play at that moment. But yes. So in this case, he’s not defining as gay and queer, and yet he’s living in some ways what we’d consider a queer identity for at least a piece of that time. What does that mean? Well, for Kuwasi, what it meant was loving life. It meant not making those kind of distinctions as… say.. “you are white” or “you are a white anarchist, so I can’t work with you.” The question is: “are you down with the struggle? Are you willing to do the work?” And you know, today in 2019, we see organizations. I don’t know so much about here in the south east. But you know, in New York, we have different parts of the Anarchist Black Cross Federation and former political prisoners like Daniel McGowan. And, you know, we have a group of radical anti-imperialist anarchists. I don’t care if you’re a Marxist-Leninist, I don’t care if you’re a social democrat. You know, not so many social democrats doing anti-authoritarian and political work. But nonetheless, the idea is if you’re down with the idea that this empire must fall. You don’t say “you’re into non-violence, so I can’t work with you”, or “you are in the wrong struggle, so I can’t work with you.” We have to move beyond our grandfather’s… I would say, false dichotomies. Our grandfather’s battles. It’s not about… It may have been at some moment, then, necessary to say “I’m with Malcolm, I’m not with Martin. I’m a Malcolmite.” But this moment, 50 years later, one does not have to choose. There’s an article co-written with some members of the movement for Black Lives, myself, and a couple of other comrades in a book of mine called White Lives Matter Most – And Other Little White Lies available through Kerbleblespleb, but also published by PM Press that co-published A Soldier’s Story. And the title of that chapter is “Refuse To Choose. Neither Malcolm nor Martin.” Refusing to choose between our grandfather’s battles, we have to transcend those battles to another moment. Who in some ways personified that transcendence? Kuwasi Balagoon.

Bursts: I’m curious, also, like I see the importance of the point that you’re making. I think that for me, an exciting part of this conversation is that and about reading this edition is that he made conscious choices that differed from so many of the people around him. And the uniqueness and what have you. And so exploring the reasons as to why he would have been drawn to… like, if you are deciding if you’ve gone through the national split in the Panther organization, and have chosen to not side with the national leadership and have critiques of centralized authority. And you’re drawn towards the writings of Malatesta, or of Kropotkin, or like others, some of the other names that are mentioned in the book. It’s interesting for me, it’s like not not a political development that most people describe, and also the kind of thing that more doctrinaire members of a movement could like conflict around, right? So I kind of wonder, and also, I brought this question from Anarchist Prisoner, Michael Kimble, who’s also gay and black, in Alabama politicized inside the system.

“What sort of conflicts did come? Or how did how did that jive with his co-defendants or with his comrades inside? Did it lead to conflicts? Or were people able to be like, ‘well, you have your way of approaching things you ask important questions. Labels are aside, we’re in movement together?’”

Matt Meyer: Wow. And thank you, Michael Kimble, and an all power to you. Not just for continued survival on the other side of the wall, but but bringing out a profound question like that one to us here today. That is a complicated and interesting question. And I’m already spinning with three different directions and actual citations to go. Because also, Bursts, you spoke about the splits. And and I think that’s worth talking about. But let me deal with Michael’s question first, as as best as I can. My understanding of the history, my reading of Kuwasi is that that latter piece was the most common. Kuwasi because of his commitment, because of his extraordinary work ethic, because of his love, which just was bursting out. Again, in the writings I’ve seen, you know, in his writing and his every moment, it just was uncontainable. So that energy, I think, put him in a place where most people were not saying, “Oh, these ideas are too challenging. This is too crazy. This is too outside of the box.” I think Rather, they were like, “it’s crazy. We’re going to figure out a way of working with it, you know, Kuwasi is unique. Kuwasi is amazing.” But So I think that’s the main answer in terms of his life. But I think it’s also very important to know that our versions of the history of back then are often way more over simplified than they should be. And so as a movement, historian as a peace researcher and justice researcher, I want us to look much more carefully at the nuances of what happened back then. And now I’m going to give three citations about that.

Another book that PM Press put out that I was involved in, and no, I’m not just doing a public service announcement to sell copies of my books. But this is one that I co-edited with a sister. She’s got to be one of the greatest organizers in my tough city: New York City, within the black movement. Today, she’s the chair of the Malcolm X Commemoration Committee. And her name is Déqui Kioni-Sadiki. And Déqui and I co-edited a book called Look For Me In the Whirlwind: From the Panther 21 to 21st Century Revolutions. Now, some listeners may think “oooh, Look For Me In the Whirlwind! I think I kind of remember that was a book that Panther 21 wrote and published, you know, autobiographical, back in the day.” Yes. And that book had gone out of print and even members of the Panther 21, who were still alive and out of jail would go on eBay and be like “$400?! I can’t pay that I was at what I was in that book!!” So we took the entire book from cover to cover and republished it, but like this book A Soldier’s Story. We added in many, we actually doubled the size of the thing, we added in another 100-200 pages of contemporary reflections and analysis. And so that was especially done under the leadership of and with surviving members of the Panther 21. Like especially Sekou Odinga, Dhoruba bin Wahad when he’s not in West Africa. He’s based here in the southeast in Georgia. Jamal Joseph and others. And the reason I bring out that book, because it talks about the Panther 21 case, is that while understanding in some deep ways about the east/west split, it also understands that some of the nature of that should be more understandable than we make it. There are nuances we miss. One of the simple ones. Simple? complicated? simple. complicated. Internationalism. The New York Panthers and the Panther 21 were especially internationalist. They were the ones mainly, Sekou himself, and others who went to Algeria, and founded and built the Black Panther Party International. And that internationalism, which now we have technology and tools that should make it easier for us to communicate across the borders. There’s an anarchist concern, what are these borders anyway? Well, we have the technology to be true internationalists. But, we haven’t necessarily freed our minds. We haven’t necessarily freed our consciousness. We haven’t necessarily freed our history, in order to understand the level of internationalism that they were doing back then, and how we need to build upon that, understand it and deepen it today.

I’ll give a second example. Even the West Coast, even the other side of the split, the leadership of Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, it should be known, and it is often not known and forgotten, put out ahead of their time, a statement in favor of gay and lesbian liberation. It’s not the most publicized of the Black Panther documents, but it’s there. And it’s there because of their own visionary struggle. So people like Kuwasi Balagoon may have been visionary 10 times further out the field. But there was still more vision, more analysis, more depth, more nuance, and conversation and debate within those structures there, then we have come to really believe and understand. So even as there were splits, and even though there were harsh debates, sometimes those debates could be contained in a place where we loved one another anyway. And again, my reading for Michael and for your question is, when Kuwasi was in those debates with his comrades in the New York and East Coast Panthers, they weren’t primary contradictions. They were all “we’re gonna work together, we have our differences in personality and character and approach. But ultimately, our eyes are on the same prize.”

I said three, I’m going to name the third and last of them. And it’s another PM Press book. Kuwasi wasn’t the only Panther who was way ahead of his time. And Sekou is not the only, and Dhoruba and Jamal are not the only surviving Panthers, who are way ahead of their time. So I would like to name another of the still remaining Black Panther black liberation movement political prisoners who is inside. Whose work is so visionary, and so proficient and so profound, and so necessary for advocacy, especially, but also all people looking to make real deep struggle. That man’s name is Russell Maroon Shoatz. Maroon, we had a successful campaign some years ago, to get him out of solitary confinement. 22 plus years of torture. State sponsored torture, under solitary confinement. He’s in general population, but he’s still in prison. His health is not so great. And he is a visionary of little equal. His understanding of an analysis of economics and eco-socialism, of anti-authoritarianism, of looking at building Maroon cultures of resistance. And why he took the name Maroon, are absolutely reading for 21st century revolutionaries. So looking at Russell Maroon Shoats, his book from PM Press is another place I’d look to for the kinds of things that Kuwasi epitomized. This idea that one can have struggle within an organization, even at the moment, and certainly upon historical reflection 40 years, 50 years later, we have to have that kind of struggle to build a stronger, better, richer, deeper, more effective movement that will smash the state.

Bursts: And that’s Maroon the Implacable.

Matt Meyer: That is the name of the book. Yes.

Bursts: Well if you know anyone, I’ve talked to Russell Shoats III to try to get him on the show, and it just hasn’t worked out. But if you have anyone who would ever want to come on and talk about his case, and try to amplify Maroon’s words, and also his case, and a push to actually get him out of prison, please send it my way.

Matt Meyer: I will say this now. And I appreciate that and we’ll make it happen. I was with with Maroon’s daughter, Teresa Shoats, I was a national co-chair of the campaign to free Russell Maroon Shoatz in that year, year and a half when we were doing the work to get him out of solitary. And I actually just came back from Sri Lanka, where Quincy Saul one of the co-editors that book along with the late, Fred Ho. But Quincy is now in Sri Lanka and Fred’s no longer with us. But I will tell you that in addition to absolutely pledging to help get Russell or Sharon or Theresa Shoats on the show, I think we’re going to see very soon in the next maybe month or so, a re-intensified a reinvigorated campaign for compassionate release around Maroon in particular. Look, it’s one of the complicated things, because again, we’re individualists and we’re institution builders, we believe in the collective and we believe in our own hearts and minds. So yes, we build movements that are focused on individual political prisoners and their release. That was just a very strong campaign. That was put forth that’s building now for release of New York State prisoner. Jalil Muntaqim. So I think I’m telling you now a little preview, there’s going to be a re-intensified campaign for compassionate release for Russell Maroon Shoats, at the same time, all of these movements from Mumia Abu Jamal, etc. all say, FREE THEM ALL. And so when I say look at the National Jericho movement, and its website, it is going to ultimately be about freeing them all.

Bursts: So I know we’ve only got a few minutes left. But Michael Kimble had another question, or he had a couple of other questions, but one of them is:

“I’ve read much of Kuwasi story, but never anything about organizing in prison. Was he involved in organizing his fellow prisoners?”

Matt Meyer: And give me Michael’s other question, because it’s so profound, I want to get them all and see how many as I can cover

Bursts: The other question:

“What roadblocks, if any, did Kuwasi encounter from those he struggled with because of his sexuality and adherence to anarchy? And how did he deal with it?”

But so the the part of that that we didn’t talk about was in terms of his sexuality.

Matt Meyer: Right? It’s a very similar answer to the previous question around differences in general. I also think, for a certain amount of time, as I understand it, Kuwasi’s relationship was when he was in prison at the very end of his life. So it was less about his comrades in the Panthers who were out, and more about the people around him in prison. So in some ways, that segues into the previous question about his life in prison. And I think it’s very, very good to lead into that question as one of our later questions, because it leads into another political prisoner whose name I’d like to mention and who has books written or published by PM Press. And that’s David Gilbert, North American, anti-imperialist white dude. David Gilbert. David’s a close personal friend of mine, and of course, we want David to come out as well. The last years of Kuwasi’s life were spent in prison in the same in the same institution as David and and so they had… not an ability to have that much depth or closeness, you know, prison still constraints you even with fellow prisoners. But there was an understanding that Kuwasi’s relationships like the relationships of most people in prison are individual or personal and not about judgment. So I think that’s the main answer to that question about the sexuality and sexual orientation.

But the more question about organizing is key. Like Maroon, Kuwasi was a master organizer. I think in some ways Maroon actually has built cadre. That’s what he’s in solitary confinement for, he was in solitary because he kept producing within the prisons that he was mini-revolutionaries or maybe not so mini. He also escaped from prison twice. Kuwasi was known to escape from prison. So the fact of the matter is, the essence of conversation was about organization. And though there may not have been a particular campaign, what he did in his work inside prison, was to explain what revolutionary nationalism, anti-authoritarianism, black liberation, was. Black liberation, black liberation, what did it mean to free the people? What did it mean to free the land? What did it mean to be a black revolutionary in the spirit of Malcolm? What did it mean to have armed self defense and self defense in general, as a principal? What did it mean to create programs like the free breakfast program? To understand that housing, that education, that food that these are rights and that people shouldn’t have to beg from within their own country for rights. People should be able to free themselves and provide for themselves. And so that organization, that consciousness raising that education was part of what Kuwasi did probably every waking hour of the day, and that was his organizing in prison.

But I also bring David Gilbert’s name up not because he just witnessed some of that and described some of that, but also because Kuwasi died of AIDS. And he died in prison of AIDS. When it became clear to the fellow inmates and to the large community of people outside, who loved Kuwasi, that he died, he died of AIDS. There was a certain shock, the way, there’s always a shock when you lose someone who is vibrant and is alive and who’s there. And then they’re not there. Even if someone’s ill for some time. But there’s also that shock of recognition that doing something about the AIDS crisis in prison, was absolutely vital. And so David began at that point, in the light of Kuwasi’s death, and in the years after Kuwasi’s death of developing in New York State, what ended up being one of the first national programs of peer education within prisons, around HIV/AIDS and HIV/AIDS prevention. And, you know, we can’t say how many, countless lives that saved and and how many people inside and outside had their own understanding of what it meant to have safer sex and what it meant to have protection and even within the prison walls and outside of the idea that HIV/AIDS could be contained, not because of any conspiracy theory of how it was created, or who was created, but simply because of the way and by the way we relate to one another. And that peer program that David helped pioneer, was absolutely part of, I would say Kuwasi’s legacy. And it’s an organizing legacy that affected the New York state prison system. And unfortunately, as we know, two steps forward one step back, sometimes it feels like two steps back, but you know, the the struggle for creating humane programs within the prisons is a difficult one at best. But we do have brothers inside like Michael, who’s asking these profound questions, obviously doing his own work. And I think when and where it’s possible, creating little breathing spaces, or more than that, is still important and imperative as much as we need to be militants and revolutionaries. No revolution in the history of the world has ever been made without many, many, many reforms. So of course, we want to abolish prisons, we want to abolish the prison industrial complex. But on that road, reforms to make Michael’s life a little bit easier, is definitely something we need to do. We also want to free them all.

And lastly, I’ll say this, we have a little call in that I got from Lynne Stewart’s husband, Ralph Poynter, great black liberation leader and educator in his own right, and people hopefully know Lynne’s too, with the great people’s lawyer who was herself a political prisoner, and passed away some years ago, outside. But, you know, Ralph said and he is right to remind us that in addition to all of these key figures we named. Be they those who have gone before Like Kuwasi Balagoon those were inside we need to fight for their freedom. Sundiata Acoli, Russell Maroon Shoats, David Gilbert, Imam Jamil Al-Amin, etc, etc. There are hundreds and hundreds of unnamed heroes and sheroes who are languishing inside. Often for nonviolent offenses, often for non-offenses for trumped up charges. If their name is Trump, they wouldn’t be inside they’d be outside. And we have to work both to enable their survival, but mainly to free them. Because Freeing them all is in part, how we free ourselves.

Bursts: Cool. Well, that’s a great note to end on. Matt, thank you so much for taking the time to be in this conversation with me. I really appreciate it and I hope you have a great presentation tonight.

Matt Meyer: Thanks for having us.