“It Did Happen Here” with Mic Crenshaw and Moe Bowstern

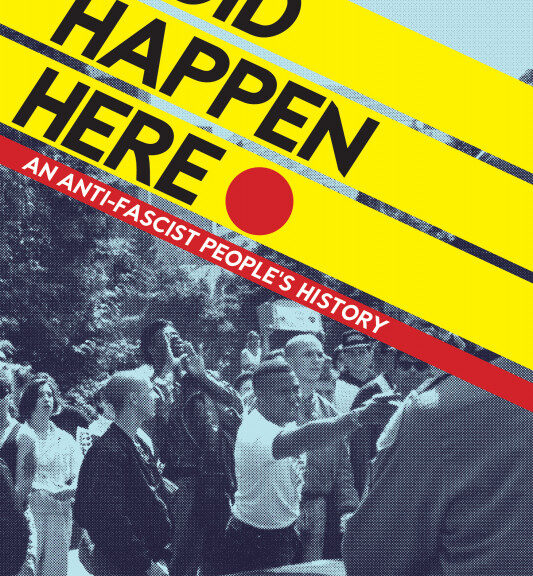

This week, we’re sharing an interview with 2 contributors an amazing history of anti-racist organizing in the late 1980’s through the mid 1990’s in Portland, Oregon, and with ripples across the so-called USA & beyond. In 2020 KBOO radio released a serialized podcast which became the basis for the book.

It Did Happen Here:

Mic Crenshaw:

Moe Bowstern

People Mic mentioned who were attacked for being white anti-racists in Pdx:

- June “T-Rex” Knightly https://heavy.com/news/june-knightly/

- Michael Reinhol: https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/michael-reinoehl-antifa-killing-deputies-wont-be-charged-1230943/

Mic Crenshaw was born and raised in Chicago and Minneapolis and currently resides in Portland, Oregon. Crenshaw is an independent hip hop artist, respected emcee, poet, educator, and activist. Crenshaw is the lead US organizer for the Afrikan Hiphop Caravan and uses cultural activism as a means to develop international solidarity related to human rights and justice through hip hop and popular education. Crenshaw was a founding member of the Minneapolis Baldies and Anti Racist Action. He was a coproducer and narrator of the podcast version of It Did Happen Here. Moe Bowstern is a alum of the anarchist space in Chiacgo known as the @-zone that lasted from 1993 to 2003. She’s also a writer, laborer, Fisher Poet, and DIY social practice artist. Moe is the longtime editor of many publications, including the commercial fishing zine Xtra Tuf. She contributed to the writing of the book version of It Did Happen Here and lives in Portland, OR.

For the hour, we talk about the book and podcast, the reach, the resonance to anti-racist struggle today in Portland and beyond. We also talk about the toll of the violence faced and engaged by folks pushing back the organized white supremacy of the day, police and institutional violence and other, related topics. If you would like people featured in this book to come and speak at your institution, you can reach them at ItDidHappenHerePodcast at gmail dot com, through PM Press, or via the IDHH instagram.

This book was published by PM Press as a part of the Working Class History series. Another featured title in that series that was recently released was a similar documentary history with a really good narrative on the history of Anti-Racist Action in the 1990’s and early 2000’s throughout the midwest of Turtle Island, both in so-called Canada and the USA, and bits of other areas. Hopefully we’ll feature a chat with one of the contributors to that book entitled We Go Where They Go: The Story of Anti-Racist Action soon on this show.

. … . ..

Featured Tracks:

- Doom Town by The Wipers from Over The Edge

- The Movement by Mic Crenshaw from Earthbound

- John Wayne Was A Nazi (Hip Hop Remix) by Audio Assault, MDC, scott crow, Sole, Mic Crenshaw, Sima Lee

. … . ..

Transcription

Mic Crenshaw: My name is Mic Crenshaw, he/him pronouns. I live in Portland, Oregon, and I’ve been here for about 30 years. I’m from Chicago and Minneapolis.

Moe Bowstern: My name is Moe Bowstern, she/her pronouns. I’ve been living in Portland, I started moving here in 1996. And I came from Chicago, where I’ve been for about 11 years, but I grew up in Western New York.

TFSR: Thanks a lot both of you for taking the time to have this conversation. And thanks for these amazing two projects that we’re going to be talking about right now.

I wonder if you’d be willing to talk briefly about the story of the podcast, which was the precursor to the book that we’re going to be talking about, and how you were brought into it.

MC: You want to start, Moe?

MB: Sure. Erin (Yanke) is the person who, what she had told me, came to Portland in 1994. She was the executive producer on the podcast– She was going to shows, she came up from Eureka (CA). She said every time she went to shows people kept saying, “Oh, you should have been here”, what it was like just a few years ago. This was just still in a 10-year window that the podcast covers. She kept hearing people telling these stories about the town being set on by Nazis, skinheads, and racists, and how everybody got together and tried to chase them out of the music spaces. She could see a lot of the impact and the fallout of what that still meant in the scene. She just was like “Man, I’m gonna tell this story.” That’s my version of her telling me that story.

She was always looking for an opportunity. She was working as the program director at KBOO community radio in Portland. There was a chunk of money that came through the Marla Davis Fund. It was $20,000 earmarked for fighting the Christian right. And she was like, “Oh, I think this is it, I can make this grant work for this story.” She made the proposal and it was accepted. Then she reached out to Mic and Selena and they started doing interviews, and they interviewed people for a year and a half. When the pandemic hit, again, she was like, “Now’s my chance!” She started working on it and bringing everybody else into it.

I came into the podcast in August 2020 with the plan of getting it out in November. Erin had a real specific timeline, we wanted to start it– The announcement dropped on the birthday of Mulugeta Seraw. The first episode was right around the time of his terrible murder, the anniversary of it in November. She asked me to help out with the narration since that piece just kept not happening. She’s like, “Maybe we can bring in a writer and bring in Moe and she can start working on it.” I tried working on it for a while, and then I reached out to Alec Dunn, who we all call Icky. I was just like, “Man, you gotta help me do this. I can’t figure out how to create this container and work with this.” And he had grown up in Portland. It felt better for me to have the story grounded in the experiences of somebody who had lived through it. We are old collaborators from a million– we were in a band together, we’ve lived together, we’re old friends. Half the podcast Erin, Icky, and I have been friends since I moved to town pretty much. Then Erin and Julie made a film of their own together. So that’s how I got involved and how I brought Icky in. Then of course, once Icky got involved, he started dicking around with the sound and making it sound really good, doing editing. Of course, he did the layout for the book we all knew. We were hoping he would do it, but I don’t know how he would have not done it. It’s right up his alley. That’s how I understand the beginnings, and then where I came in.

MC: There are a lot of different aspects of people, places, and times in history that have converged for me to be part of this podcast. One of the co-producers and editor of the book, and also one of the narrators, along with Selena Flores. Erin did some narration as well, even though the majority of it was Selena and me. I was managing the KBOO community radio station here in Portland. I’m from Chicago. I lived in Minneapolis in my teenage years, where I was a founding member of the Minneapolis Baldies and anti-racist action and The Syndicate. These are various formations that came out of the anti-racist skinhead movement. I moved from Minneapolis to Portland in 1990 for an extended period, probably almost a year I was here. Because my mom had left Minneapolis for Portland with my little sister when she divorced my sister’s dad, so I knew I had a place to visit. I came and visited, and I liked it. Went back home to Minneapolis and then in 1992, I returned to Portland and had been here ever since.

When I came here in 1990, it was two years after the murder of Mulugeta Seraw. I was coming to Portland because I was interested in maybe leaving Minneapolis because of the toll that my lifestyle had taken on me as a young man. I had a lot of PTSD from violence. Dealing with pretty heavy alcohol and drug abuse, and I just wanted a change.

When I came to Portland in 1990 to visit my mom, I knew that I had an extended family to welcome me into the anti-racist skinhead scene. And that’s because Portland had a terrible history with white supremacist skinheads and white power gangs. And we had heard about it back in Minneapolis. Prior to my coming here, some anti-racist skinheads had reached out to other cities for support in their fight against the Nazis. Some people from our network in Anti-Racist Action responded. So, prior to me even arriving in Portland, some of my best friends from Chicago and Minneapolis that were anti-racist skinheads, and also part of the ARA network had come to Portland and helped the Portland anti-racist skinheads confront some of the Nazis that were so problematic out here. So I have a very personal relationship with the story that we tell in the podcast. I was part of this movement that took hold of Minneapolis and Chicago, but played a very supportive role in what was happening here in Portland and then actually moved to Portland.

Many, many years later, I wound up managing KBOO, when I met Erin Yanke. Erin and I were close at KBOO. We were friends and co-workers. And Erin heard the story of me being an anti-racist Black skinhead. She knew that I was working on my book, which I still haven’t finished, that PM Press is also going to publish. She asked me when the book was going to be done. And I was like, “I don’t know. I’m really slow with my book. But I think to get it done, I’m gonna go home and interview some of the people that I grew up with.” The tentative title of my book is Black Skinhead. I was going to tell the story of being a Black anti-racist skinhead in Minneapolis Baldies. I went back to Minneapolis and Chicago to interview people. And Erin was like, “What do you think about using some of those interviews for this story that I want to tell through a podcast about what happened here in Portland?” Erin approached me and said, “Would you share some of the interviews that you’re going to use for your book, in this effort to tell the story of the history of anti-racist and anti-fascist organizing here in Portland?” And I said, “Sure.” That blending of the content that I was initially going to have solely from my book into the podcast created this collaborative project where now I was collaborating with Erin and Selena. That’s when Erin let me know that Moe, Julie, and Icky were all willing to support the production of the podcast. For about a year and a half, I helped gather a lot of the people that we wound up interviewing from Chicago and Minneapolis specifically. The podcast came together. And then PM Press was like, “Hey, what do you all think about putting out the book?”

TFSR: That’s awesome. Thank you. I enjoyed the podcast when it came out, it hit me from the side because I’d heard little bits of this history before. I think bringing in the voices of people, their actual stories into this scripted narrative structure and contextualizing it, plus all the soundtrack to it, just all of it blended made these easy, relatively short episodes that kept me waiting for the next one. So, good on y’all.

It seems so perfect. When I cracked open the book version of this, one of the first interviews in there– I forget which one it is off the top of my head, but I was reading it, and I was like, “I know that story”. I’ve heard these words before, getting to hear that voice in my head then, getting to have not like an expansion of that story with more detail that didn’t make it into the podcast, whether because of KBOO’s rules, or because of just the format being different, was amazing. Especially alongside all of the graphics that you all included in there, all the flyers, all the photographs. It fleshed out some of this experience that I wouldn’t have gotten otherwise. So, thank you very much.

MC: Thank you, Bursts. One of the things that I’m enjoying is hearing about the impact that the podcast has had on people. I don’t think I’ll ever get tired of it. Because there are similarities between the types of things that folks point out. But being that we’re individuals, we have this really subjective experience and so each person’s experience, even though they’re all these commonalities is a little bit different. When I hear about how different people remember that time and how they get to recall and relive things through listening to the podcast, I guess, one of the biggest benefits of that for me is that I really sense the power of the Collective. First in the team that created the podcast, because I couldn’t have done this by myself, but it was everybody’s skills coalescing that made it the powerful thing that it is, and then to understanding that this is a national story. There are people all over this country who have some skin in the game or something impactful about that time in their lives — if they’re old enough. I really enjoy that. It’s profound.

TFSR: Besides the people that were involved at the time, and those relationships that you have, it’s also a multi-generational story. Obviously, the time when this came out at the start of the pandemic, Portland had already been suffering a wave that lasted a few years of groups like Patriot Prayer, the Proud Boys, and other neofascist formations taking space, fighting people in the streets, attacking people. That was one reason I thought it was so powerful was to hear this, not only a resonance from struggle in the past, but an opportunity for people who were organizing now to hear the voices and experiences of the people back in the day, and who are still here and still struggling in the same– maybe in a different way in some cases. People have retired from street combat, and they’re writing or researching or doing audio work, or writing books. I wonder what kind of feedback y’all have gotten in that way? I know the podcast stream has a few public events, where you took some Q&As. What kind of impact have you measured from the podcast?

MB: We had that really sweet event in the park. I can’t remember what the group was called. It was a People’s History of Portland, a sort of people’s history project. It was young people who were inviting different groups to just tell stories from Portland history, and they invited us and set up mics for us. We had a couple of guests come. We had Tom T come, who was a Portland Baldie, he was an ARA member I think also. Who else came? Or was it just Tom who was the guest? And all of us were there. I think Acke was in the audience, and the rest of us were on a panel. This was in April. I remember when episodes were dropping, getting feedback from people who were spending their nights in the streets, down at the wall, down at the fence. Then I had one person who would be texting me about the response from their little crew that they called The Homies. It was awesome to feel that wave sloshing back and forth, we were putting this stuff out, and then it came back to us. We were able to feel that definitely at that event, and there were hundreds of people there. It was really cool. It was a listening event. We listened to episode 2, which is about the murder of Mulugeta Seraw. Then there was a little bit of a Q&A. It was pretty powerful. It was great.

And I like the way Mic puts it, where you are just like, “I don’t think I’m gonna get tired of hearing about the podcast.” The one thing that is hard about it, in the two years that people had in the pandemic, everybody has a podcast. It’s like you say “Yeah, I did this podcast”, and they’re like, “Oh yeah, right.” And I have to add, “No, you don’t understand. This podcast is a sledgehammer!”

MC: To me, one of the more important things about this podcast is that there’s a captive audience that finds their way to the podcast through word of mouth, through social networks, and the people who need to hear it, are hearing it. But it’s not because I’m spending 45 minutes on social media five days a week to promote it. I think capitalism demands this promotional aspect. We’re doing promotional work and as a team, it’s a lot easier and more effective than if we were trying to do it as individuals. But the thing about the podcast is it’s relevant. It’s looking at issues that are central to this society, the foundation of this country, and how those issues manifest, and impact our lives daily. I don’t care what generation you’re from, if you’re alive and breathing, and many people aren’t here anymore — there’s part of this story that whether you’re aware of it or not, it matters.

When we look at racial justice, when we look at capitalism, when we look at systems of oppression, all these different aspects that define our reality intersect with these personal stories, and the confrontation that is at the center of the podcast is a life-and-death confrontation. And from that life-and-death confrontation based on community defense and violent racial terror, ideological orientation and political consciousness emerges. When we started fighting Nazis in the streets as teenagers, we didn’t think of ourselves as activists, we didn’t know what an activist was. We grew into the role of being politically conscious and oriented to social justice activism only because we were compelled to do what we felt was right. And it was at that time that older people in the community who identified as peace activists or anti-war activists, feminists, or anarchists, were drawn to what we were doing organically. That was when we began to get the political education like, “Oh, what do you mean, people were actually doing this before we did it? Oh, we’re part of a continuum. People have historically stood up against exactly what we’re standing up against now.” The story we tell is centered around the ‘80s and the ‘90s in this country, but fascism has continued to threaten all of our existence. And that’s why it’s still relevant.

I remember when Obama run for president was when we first started to see a certain kind of backlash and a move to the right because he was a non-white person who looked like he was going to win the presidential election. That is happening in the context of brutal late-stage Capitalist gutting the social safety net that’s been going on in this country for decades. Vanishing entitlement, fear and xenophobia, and white folks going “We can’t lose the privilege that we have.” And that’s what at the center of all the fear-mongering that ever happens in this country, is the threat to white privilege, that shifting realities represent. Going from Obama into Trump, we continue to see this push to the right. And these paramilitary organizations, these confrontational fascist bastards showing up in the cities, and it happened a lot here. Portland was a hotbed for that, like you said, Patriot Prayer… I remember seeing these guys yelling. I’m like “These motherfuckers are trying to get hit.” They are so far right, people who are typically celebrated by the right, military veterans, [Patriot Prayer] would go up to people who were signifying that they were combat veterans or military veterans in the public in the recent wars, foreign wars. And they would confront them. and scream the most disrespectful shit at these people because they were trying to start a fight.

That was the first thing I noticed, and that was during the Obama years. I’m like, “There are people out here who are so determined to instigate a situation that will escalate into violence, that if this shit catches on, the streets are going to be really dangerous.” And, sure enough, Trump comes in, and there’s a proliferation, with the Proud Boys and the Boogaloos, and all these different people. What starts to happen is that these people are becoming emboldened by Trump’s message and rhetoric, they’re violent, they’re confrontational, and they’re starting to be supported, they’re starting to find support and a political base of people who are sympathetic to their fear-mongering. Once again, we start to see when they come to protests and demonstrate and counter-demonstrate that they’re being protected by the police. Now they’re carrying arms. And that’s the context in which any of the demonstration culture around the Movement for Black Lives, anything that was around the rights of queer people, anything that was around reproductive rights, these guys are targeting the people who are in the streets demanding social justice and they’re violently confronting people. Now we’re starting to understand like, “Oh, the fascist threat that we faced in the ‘80s and ‘90s is on steroids.” And we could go on, we have an environment now where activists are being murdered and getting away with murder, and anti-racists, anti-fascists, pro-reproductive rights activists, and people who are standing for the rights of trans and queer people are being hunted down, and murdered. The people who are killing them are getting away with murder and are being celebrated as heroes.

The point I’m trying to make is that what we’re talking about in the podcast has only become more relevant every month. Because people are desperate to understand like, “What can we do? What was effective? And what’s the way forward?”

MB: The thing that I always notice about the story as the podcast tells it, and as Mic lived it, and his experience of it and the people that were involved like Jon Bair and Michael Clark and Tom T, Peter Little, and the stories that they tell are noticing how young these guys were. A lot of those stories that you read about in the book, or you hear about on the podcast, these kids are like, “I was 15, I was 16. I got thrown out of my house. I wasn’t living at home.” A lot of the kids who ended up as SHARPs or with ARA were young men and they already had some sort of disruption in the home that got them out. Finding each other and creating a loving brotherhood together where they had each other and they had each other’s backs…. Mic always points this out, when you look at the photographs in the book, these are personal photographs that Coyote Amrich let us use, that have never really been published. You can see the light in the eyes of the people who are the subjects of the photos because they’re looking at people they love. These were relationships that existed between folks. It wasn’t just taking pictures of skinheads on the street, it was friends. You see the picture of Jon Bair in chapter nine and his face is just open. When we opened the book at the little party for the people who participated in the book, just opening to that page, I could just feel the wave of emotion coming off of, I think it was Jonathan Mozzochi, when he looked at that image, and he was just like, “Oh, my God, look at him.”

The point is, those kids also exist today. There are plenty of people who can’t put up with the fascism in the home or had to move out for whatever reason, especially with this attack on trans kids and immigrants and on anybody who isn’t falling in line with the fascist understanding of personhood. There isn’t a way to connect with people, the trust between generations is just decimated. You asked about my experience in Chicago, I made my way toward the anarchists, I was working with the Women’s Action Coalition, which was a short-lived group of women in the spirit of ACT UP. ACT UP really influenced a lot of the activism that was happening in Chicago in the early ‘90s. Also throughout the story, Scot Nakagawa was a member of ACT UP. The model that they were giving us was a big, public, artistic, creative confrontation with the media. And that had been happening in the past, the YIPpies [Youth Internationalist Party] had done stuff like that, too, but doing it on a much more confrontational scale. At the time, Operation Rescue had come to Chicago and was curtailing abortion rights attacks, chaining themselves to clinics, and starting very aggressive attacks on women’s rights, they would go on to kill Dr. Gunn, a man who performed abortions, just murdered him. There was a lot of turnout and that’s where I got involved with a Women’s Action Coalition.

Then at one of the demonstrations, I met a bunch of kids who were way more my speed. And they all had colored hair, which at the time was very unusual, Manic Panic hair. They were just hilarious and fun. And I ended up going home with them. And that was the end of me and the Women’s Action Coalition. I started hanging out with the anarchists. One of the things that we would do was walk around at night with cans of spray paint and hunt down Nazi graffiti. We were living around Wicker Park at the time, and it was up, it was up! People would let us know throughout the day, and one person would create a little bit of a map. And then we’d all go out at night and within crews of two or three people and hit it and cover it up. I remember when ARA started, maybe in 1992 or 1991, when people in Chicago started getting involved in ARA. At the time I was fishing four months a year, and then six months a year on boats up in Alaska, and I was usually the only woman on the boat. One of the things about the Anti-Racist Action, it was a level of very male-dominated and a level of intensity that I already lived in for four months of the year. I can remember being like, “I love you guys from over here… I’m just gonna keep working on the women’s stuff on these months when I’m not up to my eyeballs and dudes telling me how to do things all the time.” I look back and there were people around me that were doing that.

We were participating in terms of occasional tabling and running the A-zone and just connecting people. We held a space for people to come in and do stuff, smaller organizing like that. It was Sprite, who was on a much more national level. He was very connected with prisoner support and ARA stuff. He did it for years. I remember visiting Chicago in the early aughts, and he was like “Moe, I’m still doing it. I’m still tracking down all these white supremacists.” He would find them on the internet and then go out to their houses and knock on the door. And he said that more often than not at that time, which is now over 20 years ago, it was a lot of times 14 years old kids at their computers by themselves in the basement.

This brings me back to the beginning of this point, which was that there’s a way in which the Left continually attacks itself. I know we’ve all seen it, it has lots of different forms. Even just speaking about what I was involved in the ‘90s, I have this feeling of guilt that I wasn’t part of ARA because we were all supposed to be everything instead of like, “I’m doing this, I have solidarity with you, I have love and support for you.” The right is really good at recruiting. It’s really good at bringing people in, although, they fight each other and it’s gross and stuff. I see the book and the podcast as a real opportunity to really place everyone in the continuum, as Mic said. We’re older, a lot of us are in our 50s, but we’re at least still alive. And we’re vital enough to be able to hopefully connect with people. A dream that I have, and I think I share this with other members of the team that I don’t want to speak for, but the potential events that we can have around the book, it’s just quality people who share this history in their towns from that time. As we stated in the book and the podcast, if you looked at Maximum RocknRoll at the time, everybody had white supremacist skinhead problems all over the country. You maybe felt like it was just you and your town because it was just happening. I think there’s a real opportunity to show up, do an event with local people and have a place to connect. Even if you just connect with a couple of people and connect the streams, instead of everybody being in a little pond of their own history, just break the dams and let it flow.

TFSR: I wanted to explore a little bit more about the importance of talking about the traumas that people get from doing the sorts of work, whether it be defending reproductive rights, whether it be fighting and hunting, or even infiltrating far-right groups, what have you. The way that trauma is expressed in the book, which I think is pretty interesting. It’s a thing that I think people are getting better about talking about now.

The other question that I was thinking of approaching would be to drop in and ask about the end of the book, where the SPLC comes in and sues the Metzgers. And then you see a collapse of the ways that anti-racist organizing happened in Portland. Do either of those sound especially interesting to discuss?

MB: I do want to say that I looked into a lot of that history regarding the second question. In talking to Jonathan Mozzochi, and things that didn’t make it into the book or the podcast, I just want to say that homophobia also had a real impact on the collapse of organizing at a particular level, because the CHD and the Northwest Coalition Against Malicious Harassment, were committed to the Big Tent organizing and supporting gay rights. And then when they were bringing different groups in, churches would be like, “Well, we don’t want to pay into your organization anymore, because we don’t think gay people should exist.” And that was really because of the rise of the– what was the name of that organization?

TFSR: The Oregon Citizens…?

MB: Oregon Citizen’a Alliance. OCA. So I just want to stick that in. There wasn’t just the Metzger trial, the Metzger trial happened in 1992. The Northwest Coalition Against Malicious Harassment, which marked the end and the collapse was in 1998 or 1997.

MC: Moe reminded me that there’s not any singular thread at work at any one time, no single aspect of the evolution and how things evolved and shifted was happening in a vacuum. There are multiple factors, and we have to look at the fact that Coalition for Human Dignity represented a different demographic than, say, Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice, the Minneapolis Baldies, or even ARA. What made ARA effective was that ARA was able to build alliances with Coalition for Human Dignity and other demographic groups, and it was that coalition work that made it not safe for people to be as brazenly right-wing and fascist as they had grown comfortable being.

But if we want to look at the most militant arm of all this work, it was the anti-racist skinhead scene. In the anti-racist skinhead scene, you have predominantly teenagers who are growing through adolescence into young adulthood, some of whom are starting to have kids, some of whom are starting to have more serious relationships to jobs, and trying to have stable housing. As the violence becomes more criminalized by the state, people will start to change, and shift their priorities. That’s one thing that started to happen in what started as a teenage movement.

Another thing that started to happen was that because of the effectiveness of the movement, a lot of the Nazis and people who were brazenly and outwardly and publicly fascists started to go underground. They started to shift the way that they showed up. Their organizing in a lot of cases went more into less-public places, onto the internet. People began to change the way that they looked and their fashion aesthetic because they didn’t want to be identified publicly anymore, they didn’t want to be doxxed. They didn’t want to be attacked when they were in the streets. In addition to that, I’ll just say that those were things that were intersecting in converging, is that people were getting older, Nazis were going more underground. I think some people were withdrawing more into themselves.

In Portland specifically, the skinhead network grew tired of feeling like they were being used as bodyguards and shock troops or stormtroopers for the left. They felt like they weren’t being respected as much as they wanted to be. They were always asked to do security, and people knew that they were willing to engage in violence, but then people weren’t necessarily valuing their consciousness or therefore, humanity.

MB: It seems like there was a way in which that violence was– People wanted to use the violence when it served them. And then when it didn’t, those kids were really harshly criticized and socially punished for being the thing they were asked to be. And especially what Mic was saying, they’re teenagers. We didn’t have a really great understanding that we have now. We have such a greater understanding of mental health and the spectrum that people can exist on and neurodivergence, I think a lot about identifying with that.

MC: And again, to look at the confrontational aspect of the most militant part of this movement, if we were to have two poles in Portland, where one was East Side White Pride (ESWP) and White Aryan Resistance (WAR) and American Front, and the neo-Nazi groups that wound up taking Mulugeta Seraw’s life. And then on the other end, we have the anti-racist formation that has various names from Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice (SHARP), to a Portland chapter of the Baldies.

If we wanted to oversimplify things, we could book-end things and we could look at the murder of Mulugeta Seraw on one end by the Nazis. And then we could look at the death of Erik Banks who was a neo-Nazi who was killed by Jon Bair. And we have to understand that when Jon Bair killed Erik Banks, there were some pretty heavy reverberations in the scene because the response from the state was “We’re going to do what we have to do to put some people behind bars.” That probably had a chilling effect on people who were in that circle that Jon Bair was from, because people had to either figure out how to not be implicated, how to keep their mouths shut, how to lay low, how to keep their freedom or be ready to do some time because the police were looking to find out who they could put away.

On the other side, you probably had some Nazis who were like, “I don’t want to get shot. This is escalating and people are going to die.” For as macho as the male-dominated aspect of the movement that was willing to use violence might look from the outside, people are still human, and when people die, it impacts people. When people go to prison, people go “Maybe I’m going to think a little bit more seriously about the consequences of what we’re doing,” and start to ask these questions like, “Are there more effective ways to hold on to my values, and to contribute to the struggle that doesn’t involve me losing my life, or that don’t involve me going to prison for a long time?”

TFSR: I think that’s a really useful contribution that not only the podcast, but also the book provide is that it gives insights into people experiencing the violence, narrating the history of them experiencing the violence at the time, but also people like Jon Bair talking about the experience of incarceration or talking about being so stressed and feeling at war and then choosing to go intoxicated with a firearm to a conflict and not even realizing that after responding to violence coming at him, that he let off two rounds with the rifle and ended up killing a person. I think that it’s important, I feel, for people to take community defense in all of its forms, including the use of violence to defend other human beings and defend ourselves because we have dignity and we deserve that. That’s super important. I think that also giving space for people to talk about the toll that it takes. The substance use that goes alongside it sometimes as a coping mechanism, if we’re not given other tools for that. The book does a really good job of playing that out and reading some of the narratives of going through prison terms by Jon and Tom was super powerful for me.

MB: One of the things that I just noticed a bunch in doing the research, was how effectively the [The Oregonian] newspaper combined with the police, the newspaper gets most of its information from the police reports, the one particular cop really headed in labeling the kids as gangs. That was cutting them off from any public support that they may have been able to have. When you look at the story from the outside, where I was coming from, it really looks like these young men getting just cut off from all sides and ending up on an island of violence. Like Mic said: H ow do I choose to continue in my humanity and become that?

Michael Clark talks very openly about his struggles with drugs and having to be ejected from his friend group and his gang because of that. I think if we’re going to have community defense, which I believe in, we also have to remember to defend our community members and to care for them. When you hear the Reverend Cecil Prescod’s voice in the podcast is like, “Take care of yourselves”. What is the advice from this man who’s been fighting for racial justice for 60 years, and he’s just like, “Take care of each other”. That’s literally the first thing that he says. That’s something that’s easy to lose sight of, first of all when we’re under personal physical threat and then when we’re also living under this intense, brutal capitalism that we’re enduring right now. Then we also have ideologies that we’re trying to understand, live inside of, and develop for ourselves.

TFSR: I appreciate the fact that you made space in the history for talking about the difficulties of living hard lives among the youth subcultures who were fighting racists, the violence and substance abuse, the undermining by authority figures, the prison sentences like Tom T and Jon Bair [survived] that came out both in the book and the podcast. I was wondering if you’ve gotten much response on making space for those hard and inward-looking portions of the podcast. I know the book just came out, so maybe not so much reflection on that yet.

MC: There were two bonus episodes. There was one that I was particularly pleased with. Having had the majority of the podcast done, I was able to look back and reflect on some of the points that were sticking with me, overall. It was this question, Erin phrases it nicely, this question of “what is it that motivates us to risk our own safety to make the community safe, for not just ourselves, but others?” That’s the principle that underlies this concept of community defense. But it takes a toll, the trauma takes a toll. There are a lot of lessons in that, trauma is something that feels bad and it has a very negative connotation because people get hurt and people die and people are sad, and people are impacted in really long-lasting ways that are not easy. However, if you’re present with the available teaching, there are some really valuable things about who we are. To risk your safety to protect yourself, to risk your safety to protect others forces you to confront your own limitations in a way that you wind up sitting with something really authentic about yourself that you might not have discovered otherwise. There’s some truth in there that I think is deeper than rhetoric and ideological slogans and phrases.

I’ve always trusted people who have been through violence to keep peace better than people who say that they’re non-violent, but have never actually endured violence. Because I think people who’ve lost something because of the trauma of violence, have a bit more stake in not losing those things and not wanting to see other people have to lose those things. There’s something about the principle of unconditional love that underlies this work when we take a stand against things that are a threat to all of us.

If we could look at it as a polemic, and even though we know it’s more complex than that, we can understand that the fascists, their movement, and their ideology are based on fear of extermination, fear of annihilation, and the insecurity that underlies that. Their justification for violence is based on the fear of being annihilated. We’re trying to keep people safe. They’re trying to destroy the ability for people to exist. That’s what we have to understand.

There’s a lot of history that we can look at, that we could define as anti-fascist. But there’s a lot of rhetoric and propaganda about what Antifa means. I think that’s an important conversation we have to continue to have, even though it’s tired. One of the reasons that it’s tired is because there’s this oversaturation of scapegoating and criminalizing of people who say that they’re anti-fascists. The mainstream media has been so effective at influencing the way people think that when people think of Antifa, they think of people who are just assholes who want to make everybody uncomfortable, and who are so self-righteous and arrogant about their political orientation that they’re intolerant. The reality of it is, the people who were committing to this level of sacrifice were people who just wanted the community to be safe. People who wanted to point out that the people who are the most dangerous were a threat to all of us.

MB: Coming to Portland in 1996 from Chicago, I was going to demonstrations all the time in Chicago in various ways. I was shocked at the way that police treated people at the protests here. It was so much more personal, it was so much more pointed. It was so much more dangerous to go to a protest in Portland when I started coming here and hanging out. That was shocking because everything else about Portland was so small and easy. I just could go anywhere at any time by myself in Portland and never feel like I was gonna get jumped or there was any danger on the streets. But then you go to a protest and everybody was like, “Never leave alone, always leave immediately. If you’re the last ones at the protest that’s when you get–“ and it was just over and over seeing that. Watching the cops break people’s arms and the cops had the horses and they would always try and ride people over. Then there were literally documents that stated that “one of the tactics of the anarchist women was to throw themselves underneath the horses as a way to scare the police”. It was something I had never seen before. You come from a big city like Chicago, and you just think you know everything about– Well, maybe that’s just my nature. It’s like, “Oh, yeah, well, Chicago, blah, blah, blah.” I was like, “No way, man, this Portland stuff is something different.”

TFSR: It’s not like the police in Chicago are known for having a soft touch or whatever.

MB: No, I mean, those fuckers would just hit you over the head. But they didn’t care. In Portland, it was personal. They were vindictive.

MC: What you’re describing is something that I’ve been tracking. Not to say that I’ve been tracking it as if I’m the only person who’s been paying attention, but I don’t hear a lot of people talk about this. Portland, and to a large degree, the Pacific Northwest, settled by white settlers in a very systematically and systemically exclusive way, violent exclusion of non-white people, genocidal frontier push in terms of Native Americans, that happened everywhere on this landmass. But there was something about the Western settler project in Oregon specifically, that was very intentionally about “this is for white men and white men only. And whatever you guys are doing back in the East and down South and in the Midwest, we’re going to fight and keep this shit white.” White power has always been personal here because it has its origin in “if you’re going to keep this land, and you’re going to hold on to this privilege that you have, you’re going to defend it by force.”

White people who don’t toe the line are a problem. White people who are anti-racist, white people who are race traitors, and white people who will prioritize the rights of others over the rights of white people to dominate have to be dealt with harshly. We see that in the way that the anti-authoritarian white left is dealt with by the state here. We saw it with the WTO [protests in 1999]. We saw it with the Environmental Justice Movement. We see it with the anarchists. We see it with Antifa. We see it with Black Lives Matter. Because there’s a power structure that is not going to tolerate its own fucking children undermining it.

When I see the personal violence that the police are exacting on protesters, that’s what I’m seeing. When they hunted down Michael Reinoehl and shot him in Olympia, that’s what I’m seeing. When Kyle Rittenhouse gets away with murder over in Wisconsin, that’s what we’re seeing. When June Knightly, a.k.a. T-Rex, is killed by a mass shooter at a park in Portland at a Black Lives Matter protest, that man hunted down a group of women and shot five people, and they talk about him like “a homeowner”. They prioritize a fact of his relationship with private property. It is more important than the fact that he attacked a group of people who were there to keep people safe and killed one of them.

We see these things time and time again and there’s something about that. I don’t want to center whiteness because this is ultimately about liberation for the most oppressed people. We have to understand the way that radical white people are treated in this project is a direct correlation to the fact that they’re undermining white power.

MB: Yeah, totally experienced it. Totally outsized, violent reaction, and The Oregonian newspaper has been on board with it the whole way and all the big media outlets for sure. The propaganda is very effective. You just wave shit in front of people’s faces and then the next day they’re saying like, “Oh, yeah, Antifa is gonna come and destroy your house. They’re gonna take your home, so you better just get a gun.” People can have guns if they want to, it’s a hot topic right now.

You wanted us to opine about forms of anti-racist organizing currently? I’m hoping to learn more about it. I have to say, I’ve been dealing with disability and cancer, and the pandemic. So I have had to really step back. If anybody comes to one of our events, I’m super into finding out and supporting what the organizing is. I am hoping to move into an older age, I’m in my 50s. I would love to grow into a venerable, pissed-off crone that can continue to connect with young people. I have lots of friendships with young people, and the book and the podcast, both are really great. It was so fun, to just be able to vent some of my thoughts about materialism and white supremacy and capitalism and classism. The relentless attack on working people, especially working people who are not white, as Mic says, is just not the oligarchy.

I’m ready to connect with people, the book really gives me a lot of hope, to leave threads that have always been there, but they’re just hard to pick up, everybody is so hurt. I developed PTSD after getting really impacted by the WTO. And then having a violent upbringing, but not really believing in that until the WTO after that. And then trying to function in Portland, in demonstrations, and I really would love to be able to be a part of supporting, helping people learn how to support each other, when there’s conflict in leftist communities so that we can continue to provide each other with the unconditional love and tap into it, so that we can remain comrades and not have to drop out in order to be okay.

MC: Can I add to that Moe?

MB: Yeah, please do.

MC: I think the two exciting things are that the book is out, the podcast is out. The podcast is going to continue to reach people that haven’t heard it yet. The book is going to reach people who don’t really listen to podcasts. The book can be relevant.

When you pair them togethere… We were contacted by the Oregon Historical Society and we were contracted to write a high school curriculum for the book and the podcast. This information is going to be in classrooms, teachers are going to be teaching grades 9 to 12. That’s one of the more exciting outcomes because a younger generation gets to live and process this in their own time this story, this history. And the Minnesota Historical Society is bringing out Jon Bair and myself and many people from Minneapolis to do a screening of The Baldies documentary that was produced in the same period that the podcast was catching on to the audience. There’s an institutional interest in supporting the work and the work is going to be able to reach places that we wouldn’t have thought of and that’s exciting because it’s going to matter to people.

MB: Also PM Press has told us that they don’t have a timeline for events. It’s not like, “Okay, we’re gonna push your book for four months or a year or whatever.” They’re like, “You want to do events, we’ll keep supporting you, we’ll keep showing up with books.” We don’t really have a budget for events or travel, so anybody that wants to fly anybody, we’re all kind of willing to go anywhere and talk about stuff. That’s not just the folks who are on the cover of the book. It’s people who are inside the book, too, who have expressed that. For sure. So since you have a radio audience, I just want to put that little plea out there. Most of us have several jobs and we’re all just hustling to make it work, but this is a passion of all of ours. I’m really glad you spoke about that, Mic, I wasn’t sure. It’s not my thing really to bring up, but it’s something I’m so proud of and I’m really excited to have that be out in the world in that way.

MC: Yeah, me too. Let’s get some of the people that were in the book in some of the classrooms and on some of the speaking panels.

Thank you Bursts.

TFSR: Yeah, it’s my pleasure.

MB: Thank you Bursts, thank you, Mic.

TFSR: If folks do want to– Obviously, they can pick up the book in all sorts of different places. If they want, if they have the resources to be able to invite y’all or some of the other folks from the book or the podcast into their spaces, where do they reach out? Through PM? Or do you have a separate website?

MC: Yeah, they could reach out to PM. Moe, what’s that?

MB: itdidhappenherepodcast@gmail.com

MC: And follow It Did Happen Here on Instagram.

TFSR: Awesome.

MB: You can DM through the Instagram account also.

MC: Correct.

TFSR: Cool. Thank you. Again, thank you both so much for having this conversation. Mic, is it okay, if I use some of your music for the intro-outro stuff on the show?

MC: Please do and thank you for asking.

TFSR: I’ll reference it and put it in the show notes. Thank you both for taking the time and for all this work. It’s really awesome, and I hope you all have a good rest of your evening.

MB: Thanks Burst, you too. I think you do a really good job with your project. It’s been really fun to listen to you even if the information is not always fun to hear about.

TFSR: It’s fucking depressing.

MB: That interview with Leo was just incredible.

TFSR: Thank you so much. Yeah, she’s amazing.