“Interpreting Realities: Aligning Fragments Within the Prisoners Resistance Movement“

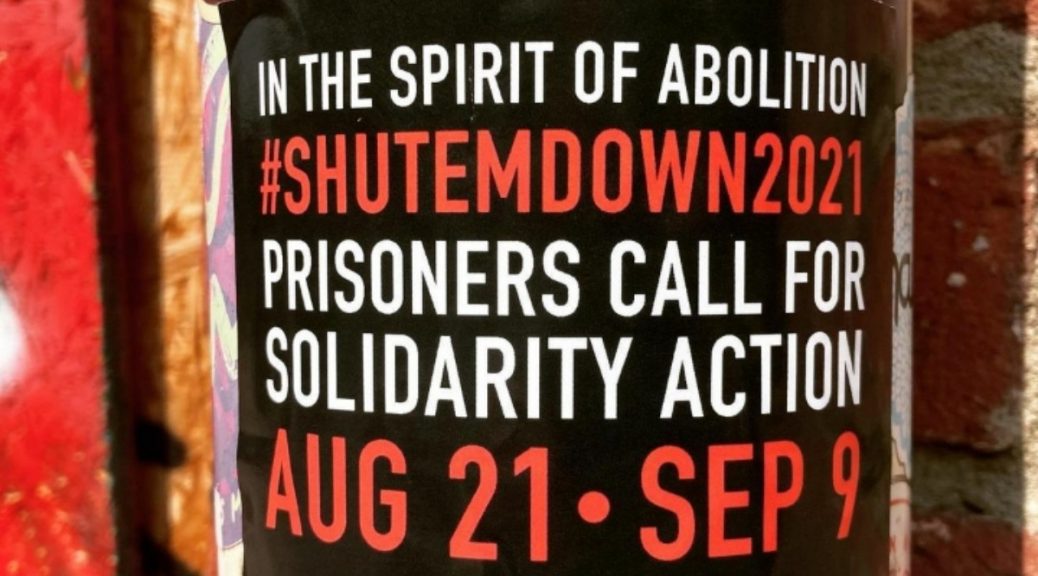

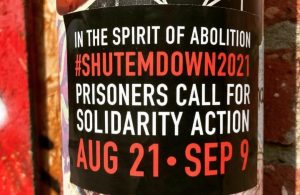

This is the second segment of a series of political discussions focused on building support for Jalihouse Lawyers Speak 2021 National call to action #ShutEmDown2021 along with support for the 2022 National Prisoner’ Strike & Boycott.

In this segment “Interpreting Realities: Aligning Fragments Within the Prison Resistance Movement” moderated by Brooke Terpstra – a longtime resident of Oakland and co-founding member of Oakland Abolition and Solidarity, which has been active since 2016 in the abolition and prisoner solidarity movements–we are joined by two panelists located within the belly of the beast– a conscious New Afrikan Komrade, located within kalifornia koncentration kamps, who is serving a longer than life sentence due to prosecutorial abuse of power, along with Komrade Underground–3rd world rebel, urban guerrilla, student of dragon philosophy and member of JLS–to discuss myths and misconceptions of the us prison structure and how these misconceptions create fragmented understandings about the prison-carceral state and forms of abolition. We also hear how the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has further isolated prisoners from the outside world.

More about JLS at http://www.iamweubuntu.com/ or by finding their accounts on Twitter (@JailLawSpeak) & Instagram (@jailhouse_lawyers_speak). You can find all three panels at https://shutemdownsolidarity.wordpress.com/

You can find a transcript of this interview in the near future at TFSR.WTF/Zines, and you can support our transcription costs at TFSR.WTF/Support

** This episode, including Sean Swain’s segment on the 50th anniversary of the Attica Prison Uprising and the massacre that follows, detail abuse and brutality against people in prisons, including of a sexualized nature, so listener discretion I advised **