This week, we’re sharing three segments. First up, you’ll hear Yara speaking about Solidarity International, a new initiative to support prisoner support and anti-repression work beyond borders initiated by various anarchist and anti-authoritarian groups networked together, including the International Anarchist Defence Fund and various anarchist black cross groups across the world. Yara’s voice has been re-recorded for anonymity. [ 00:02:19 – 00:29:02 ]

We’re releasing this in the run up to the 2025 Week of Solidarity With Anarchist Prisoners (or WOSWOP), August 23-30th, in which people are invited to gather, connect and take action against borders and against prison walls. You can find more about Solidarity International at their website, Solidarity.International, find them on their mastodon, bluesky, telegram or instagram accounts, and see the 2025 WOSWOP call for solidarity on that site or linked in our show notes. We read the statement here as well. [ 00:29:21 – 00:32:37 ]

Then, you’ll hear 2 segments from recent episodes of B(A)D News, a monthly podcast in English from the international A-Radio Network. More audios like these, plus archives, can be found at A-Radio-Network.Org

- The first of these is from the Anarchist Assembly of Biobío near so-called Concepción, Chile from the June 2025 episode of B(A)D News, featuring a chat with the art collective Mesa 8, where they discussed memory, art, and the military dictatorship that began in 1973. [ 00:33:18 – 00:38:23 ]

- Following this, Ausbruch from Freiburg in the German territory spoke with the Red Aid, “der Rote Hilfe” about their work and current challenges from it’s founding over 100 years ago by the German Communist Party (KPD) into it’s current iteration. This segment can be found in our July 2025 episode of B(A)D News. [ 00:39:12 – 00:53:34 ]

Finally, you’ll hear a segment from Sean Swain… [ 00:53:36 – 01:01:50 ]

Some Materials Related To Mentioned Cases:

- Roman Shvedov, fallen comrade

- Antifa OST & Budapest Complex including Maya who just ended a hungerstrike (TFSR ep)

- Moscow ABC and Solidarity Zone supporting Russian dissidents

- Marianna, Dmitra plus their fallen comrade Kyriakos Xymitiris, of the so-called Ampelokipoi case in Athens (TFSR ep)

- Women Prisoners of Iran facing death: Sharifeh Mohammadi, Pakhshan Azizi, Verisheh Moradi and Nassim Simiyari

- Stop Cop City 61 RICO defendants

. … . ..

Featured Track:

- Vitamin C by Can from Ege Bamyasi

Continue reading International Solidarity and the 2025 Week of Solidarity With Anarchist Prisoners

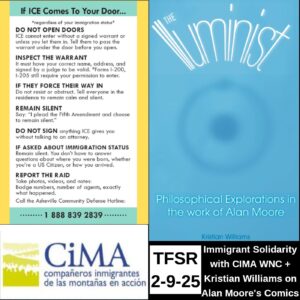

First up, Dulce, a member of Companeros Inmigrantes en las Montanas en Accion, or CIMA, a local organizing and advocacy group by and for immigrants in western NC about her experience working for dignity and solidarity in light of the current and past administrations. More on CIMA can be found at

First up, Dulce, a member of Companeros Inmigrantes en las Montanas en Accion, or CIMA, a local organizing and advocacy group by and for immigrants in western NC about her experience working for dignity and solidarity in light of the current and past administrations. More on CIMA can be found at