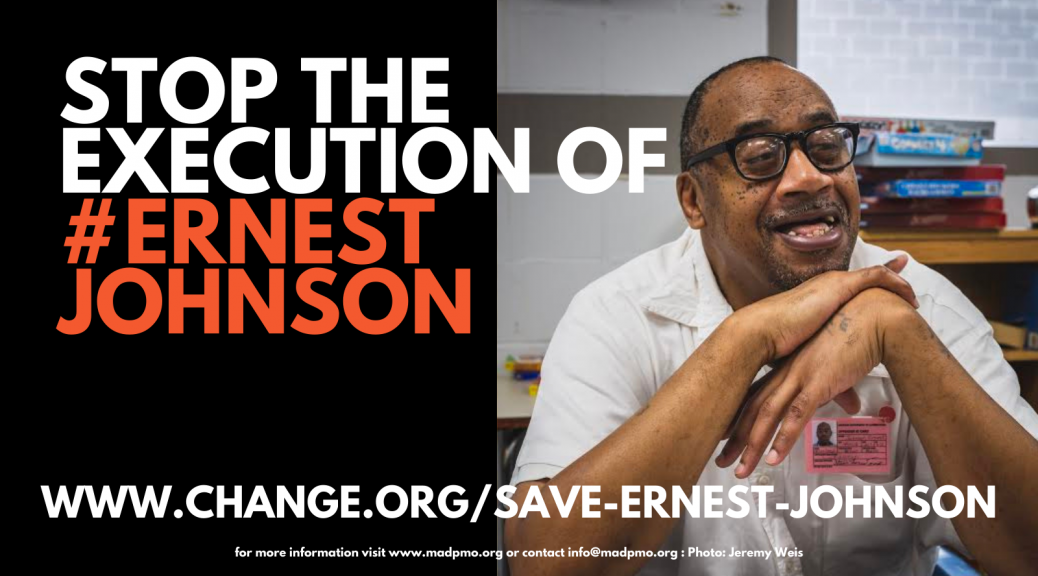

Stop The Legal Lynching of Ernest Johnson

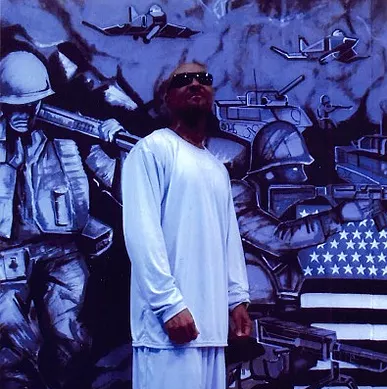

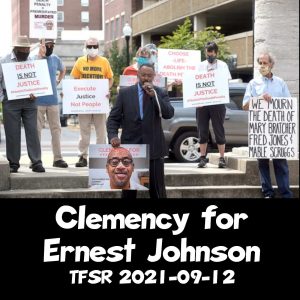

On February 12th, 1994, Ernest Lee Johnson and his ex-girlfriends’ two sons participated in the botched robbery of Casey’s General Store that took three victims’ lives: Mable Scruggs, Mary Bratcher and Fred Jones. Mr Johnson has no recollection of the murders, was in despair and had been drinking and smoking crack in the hours after his ex-girlfriend broke up with him. A Black man with intellectual disabilities and no former, violent convictions, he was convicted by an ill-informed, all-white jury with the help of Boone County, Missouri, Prosecuting Attorney, Kevin Crane. Ernest Johnson now faces an execution date of October 5th, 2021.

This week, we spoke with Elyse Max, State Director of Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty about the life of Ernest Johnson, the media and court situation he faced, his twice overturned death penalty, the links between the lynching of Black people in the US and the current death penalty, intersections of race and class in who are the victims of capital cases and who sit on death rows, the mishandling of Ernests intellectual disability in the case and other topics.

You can learn more about Ernest’s case, including ways to help press Missouri Gov Parson for a commutation of Ernest’s execution and the work of Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty by visiting MADPMO.org. You can follow their work on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram via the handle @MADPMO.

Some other useful links:

- Ernest Johnson petition at Change.org: http://www.change.org/save-ernest-johnson

- The Community Remembrance Project of Missouri: https://www.crp-mo.org

- Death Penalty Info: https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/

- Equal Justice Initiative: https://eji.org/

- “Broken Heart of America” by Walter Johnson: https://www.indiebound.org/book/9780465064267

- Just Mercy documentary: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q7MxXxFu6fI

More info on Swainiac Fest available on Instagram (@Swainiac1969)