Queer Activist Perspectives from Southern Appalachia

This week on the show, we bring you the audio of an activist panel from the recent Queer Conference held online by University of North Carolina, Asheville, in March of 2021.

The conference was titled Fitting In and Sticking Out – Queer [In]Visibilities and the Perils of Inclusion. From the panel’s description for the conference:

This panel brings together 4 local (Asheville, NC) and regional groups working at different intersections of queer community support. We will learn about the work these groups do, the particular issues that affect southern queers, the changes in visibility and inclusion for queer community, and the building of larger coalitions of liberation. Representatives from four organizations will be part of the panel:

- Youth OUTright (YO) is the only nonprofit whose mission is to support LGBTQIA+ youth from ages 11-20 in western North Carolina. Learn more about their work on their website, and support them financially here.

- Southerners on New Ground (SONG) is a nonprofit aimed at working towards LGBTQ liberation in the south. Find out more about their work on their website, and support them financially here.

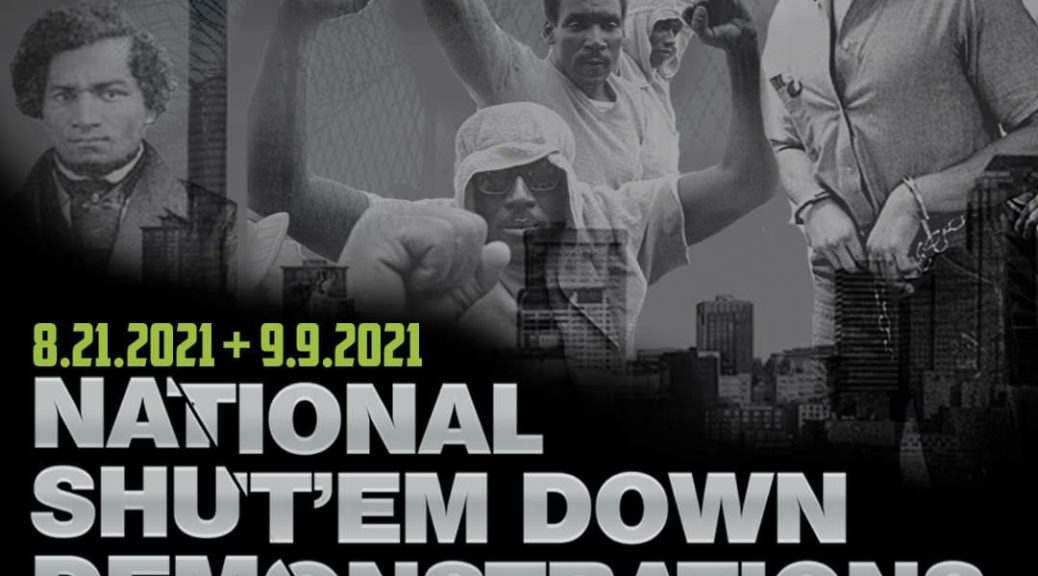

- Tranzmission Prison Project (TPP) is a prison abolition grassroots organization that provides literature and resources to incarcerated members of the LGBTQ community. Learn more about their work on their website and donate here.

- Pansy Collective is a decentralized, DIY, queer, music and arts collective that created Pansy Fest, an annual queer music festival showcasing LGBTQ musicians from the south and rural areas, prioritizing reparations for QTBIPOC artists and community members, and community education and organizing around the principles of autonomy, mutual aid, antifascism, love, and liberation for all. Learn more about their work on their website, or donate here.

Continue reading Queer Activist Perspectives from Southern Appalachia